For years now, cocoa farmers income from the sector has kept decreasing while the cost of production and living has kept increasing. Cocoa farmers, who ignited an industry worth over £131bn, are unable to afford the quality of life enjoyed by even the lowest-paid person working in the cocoa processing and chocolate manufacturing factories. However, the cocoa farmer is being blamed for everything from forced labour to climate change, etc.

The actors in the cocoa-chocolate value chain mainly the chocolate manufacturers, cocoa processors, certification agencies and government have continuously built their poverty alleviation strategies and farmers’ income improvement strategies around some of the economic oratory of increase in production leading to increased income or high-quality production leading to premium price, hence increased income.

So, if farmers upon all these supposed “help” using these acclaimed economic principles, has seen their income from the sector decrease from 16% to 6%, which Oxfam even argues has dropped to 3%, then this article is about to explain why all the strategies are deliberately made to send the farmer one step forward and twenty steps backwards. In short, this article argues that the system has been fixed against the smallholder farmer to impoverish them till the end, regardless of the quantity or quality of their production and a deliberate and radical decision needs to be made to save farmers.

This article has grouped all the income improvement and poverty alleviation strategies in the cocoa sector into two approaches. The High-quality-premium price approach and High volume-high income approach to increasing farmers’ income.

High-quality premium price approach

This approach looks at producing high-quality cocoa beans to attain a higher price and is underpinned by the principle of premium product attracting premium pricing. Ghana adopted this approach as part of its broader Economic Recovery Program (ERP). Ghana is the only producing country that generates an average of $100 premium on a ton of cocoa beans sold.

For farmers to attain the premium quality of cocoa beans, they have to spend a lot of labour hours on farm maintenance, especially weeding, which they do not do with machines but with their hands, to ensure that they do not clear the needed organic humous from the surface of the land or cut any of the plants’ roots. They use the natural sun instead of mechanical dryers towards ensuring that the cocoa beans are naturally dried and gain a lot of vitamins from the sun.

This takes a lot of man-hours, increase the production time, cost and leave them to at the mercy of changes in the climate. The beans if not well dried due to unpredictable climate can be rejected by the Licensed Buying Companies (LBCs) due to how Ghana’s Cocoa quality matrix is modelled around a high-quality strategy. So what does the farmer get in return for going through all these stress as compared to their counterparts in other cocoa-producing countries who are not focused on quality?

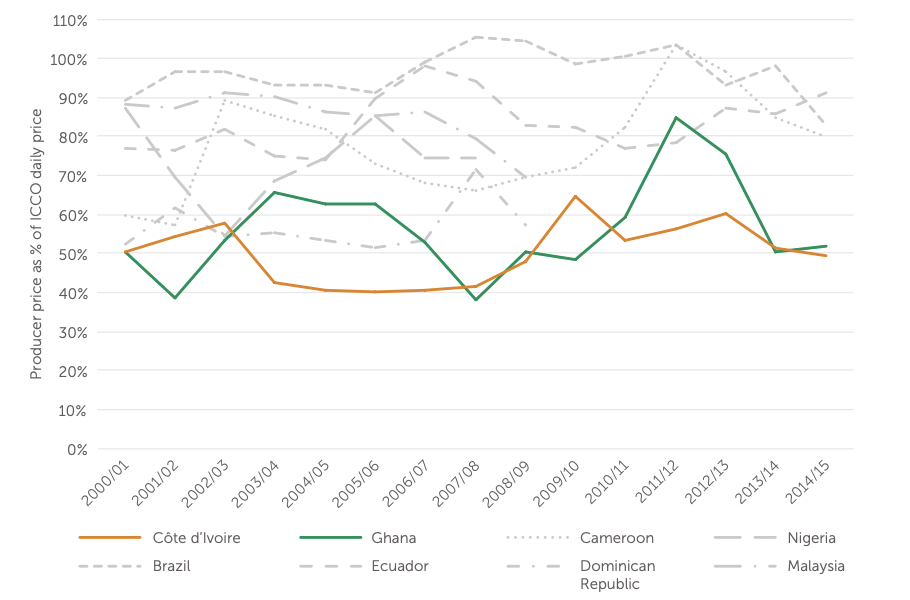

Figure 1 – Producer prices in US Dollars as a percentage of the ICCO daily prices

Source: (ICCO, 2012)

The graph above shows how Ghanaian farmers receive one of the lowest in terms of producer price as compared to their counterparts who do not need to go through the pain Ghanaian farmers deal with. This approach only created a cocoa bean brand that benefits cocoa processors and chocolate manufacturers financially at the expense of the cocoa farmers.

High-volume high-income approach

This approach looks at interventions that assume that farmers can increase their income and enhance their livelihoods if they produce more. What mostly is forgotten is that Cocoa is sold in the commodities market where demand and supply determine the price at any point in time. So, in this case, if cocoa farmer’s income is all about Quantity multiplied by price, and price changes anytime quantity changes, then how should cocoa farmers work out their income? Should they produce less to get a high price or produce more to get a lower price, and how does it improve their overall income? Doesn’t any of these two approaches bring the farmer back to square one? Below is a chart that shows the relationship production volume has with the world market price.

Figure 2 Historical overview of cocoa world prices and Ghana’s Productions from 1947 to 2014

Source: Data compiled by Marcella Vigneri and Shashi Kolavalli

Consequently, stakeholders who are interested in driving down the world market price, take a keen interest in providing interventions, aid, etc. that are geared towards increasing the quantity of production. To validate this assertation, you can check how these sustainable programmes benchmark their success on the extra yields the farmers gained as opposed to the increase in farmer’s net income/value attraction within the industry. Another way these strong actors perpetuated this production-volume increase agenda was the creation of research reports to predict how there was going to be a million-ton deficit in cocoa supply by 2020.

This prank caused panic and fear leading to producing countries and aid agencies sponsored by the perpetrators in responding positively to initiatives that increase production volume. This has led to an overproduction of cocoa with the Ivory Coast alone increase production from 1.449million tons in 2012/13 crop year to 2.154million tons in 2018/19 crop year.

Figure 3 – Cocoa Production Increase: Global Overproduction and harvest increase in Ivory Coast

This global overproduction as shown in figure 3 continues to cause prices to fall to the extent that Ghana’s Finance Minister had to threaten Ghanaian cocoa farmers that they wouldn’t be able to subsidise farmers anymore with the Cocoa Stabilisation Fund as it has been emptied and farmers may have to now face the volatile market themselves. In that case, should Ghana Cocoa Board as an organisation exist if the finance minister’s decision is implemented, reflecting on why they were established? Well, that may be for another discussion. This production increase narrative and its oversupply results now allow Cocoa traders in the West to play the hoarding game. That is, the trader buys it cheap, hoard and use it so that the trader sells it when the hoarding strategy causes a shortage of supply hence driving up prices. The processors and manufacturers also buy it cheap and hoard and use it in their productions when the traders hoarding cause a price shoot up. Below is a graph that affirms my assertation on the relationship cocoa hoarding has with world market price.

Figure 4: Relations between stocks of Cocoa and Price

Source: Thomson Reuters Datastream found in Burgering (2018) report.

This reduced price affects producing countries like Ghana to support its farmers’ income and hence reduces farmer’s ability to adhere to the labour standards required by consumers and the International Labour Organisation and improve the living conditions of its households.

So, if you are an ethical buyer, the person to scrutinise more is everyone other than the smallholder cocoa farmer. Cocoa farmers have been setup systemically to fail and there is the need to turn the tables around and focus on other ways where the farmer can draw income from every aspect of the knots in the cocoa-chocolate value chain than limiting them to the cocoa beans pricing or production volume increase as the only areas where their dreamed livelihood lies.

The writer is an International Development & Trade Analyst with a deep research interest in issues affecting smallholder cocoa farmers in Ghana. He has over 10 years of work experience within the Global Cocoa, I.C.T and Higher education sectors. Currently, he is the General Secretary, Executive Director and Board Chair at The University of Manchester Students Union, as well as a Governor at the University of Manchester Board of Governors, United Kingdom.

Twitter: @asamoahpeters

LinkedIn: Kwame Asamoah Kwarteng