Africa bears virtually no responsibility for the greenhouse-gas emissions driving the climate crisis. It is not responsible for the conflicts or supply-chain disruptions that have driven global inflation. Nor did it trigger the spread of COVID-19, let alone cause the pandemic’s economic fall-out. And yet, the long-term effects of this trio of crises are being felt, perhaps, more acutely in Africa than anywhere else.

The International Monetary Fund has estimated that Africa’s additional financing needs resulting from the pandemic will amount to US$285billion over the four years ending in 2025. But with inflation, exchange-rate pressure and unmanageable debt levels eroding the already-limited room governments have to make the needed short- and longer-term investments, Africa’s real needs are likely much greater.

Despite the remarkable resilience that the continent has shown, anaemic economic growth is compounding the challenge. Sub-Saharan Africa endured recession in 2020 for the first time in 25 years. And, according to the African Development Bank (AfDB), the region’s annual growth rate fell from 4.5 percent in 2021 to 3.5 percent in 2022. It is expected to amount to just 3.8 percent this year.

Behind these figures are countless ruined lives. The United Nations Economic Commission for Africa reports that 18 million more Africans slipped into poverty last year. Hard-won progress toward the UN Sustainable Development Goals has been reversed. Conflicts and climate-related disasters – such as protracted droughts, extreme rains and flooding – are contributing to East Africa’s worst hunger crisis in decades. The human cost is horrifying, with one person predicted to die of hunger every 28 seconds from this crisis alone.

This ought to concern the international community – and not only for humanitarian reasons. The world needs Africa. There is no path to a green, just and prosperous shared future that does not have Africa at its core. So, it is in the self-interest of the rest of the world to support the continent, not through charity or handouts, but by backing African-led solutions, especially those focused on levelling a playing field that is currently tilted to the continent’s disadvantage.

The allocation of special drawing rights (SDRs, the IMF’s reserve asset) exemplifies the problem. The IMF created SDRs to supplement governments’ currency reserves. But, because SDRs are issued in proportion to countries’ IMF quotas, poorer countries receive the smallest allocations, despite having the greatest need. Wealthier countries – which have far less (or no) need – get the largest shares.

In 2021, the G20 countries promised to channel at least 20 percent of their SDRs toward Africa. But their promises have yet to be fully realised. Faster progress on this front would go a long way toward helping African governments in the near term, especially if the recycled SDRs are channelled through multilateral development banks, such as the AfDB. These institutions could then leverage their own AAA ratings to scale up the capital mobilised by a factor of three to four, transforming, say, US$20billion in SDR-funded projects into US$60-80billion, with significantly better terms than those offered in commercial markets.

Of course, a more dynamic and expansive private sector would provide a longer-term solution. But, as it stands, African governments are at a grievous disadvantage in private markets, where they face higher capital costs, not least because of subjective, discriminatory considerations. Comparing the risk premia of African and non-African states with similar credit ratings, one finds differences ranging from 150 basis points to more than 650 bps, sometimes reflecting a lack of on-the-ground knowledge and subjective judgment.

A conference of credit-rating agencies, investors and African governments is urgently needed to address this intolerable discrimination – which amounts to a powerful brake on progress – once and for all. Again, this would not amount to charity or special treatment; rather, it would be a step toward levelling the playing field, so that African-led solutions can succeed. Removing the ‘Africa risk premium’ would unlock much-needed capital to invest in green development, including the clean-energy transition.

The Alliance for Green Infrastructure in Africa is one African-led initiative that would advance this goal. Unveiled by the AfDB, the African Union, Africa50, and other partners at last November’s UN Climate Change Conference in Egypt (COP27), the AGIA seeks to raise US$500million in grants, concessional resources, and blended and commercial finance to provide early-stage project preparation and development capital for green initiatives. By mitigating high interest rates and the lack of risk appetite for Africa, this would result in the rapid creation of a strong pipeline of bankable green projects. The AGIA aims to unlock at least US$10billion in green infrastructure investments.

Similar efforts are underway elsewhere. One notable example is the ambitious Bridgetown Initiative launched by Barbadian Prime Minister Mia Amor Mottley to create additional fiscal space for development, as well as climate mitigation, adaptation, and loss and damage. Another is the V20 group of climate-vulnerable developing countries, currently chaired by Ghanaian Finance Minister Ken Ofori-Atta.

The coming months offer several opportunities for breakthroughs. The just-completed AfDB meetings in Sharm El-Sheikh last week were an important starting point. Next month comes the Summit for a New Global Financing Pact, a major international conference on funding for development and green investment. And September will bring the G20 Leaders’ Summit in New Delhi, an event to which Africa still relies on an invitation, though its economic and demographic weight entitles it to permanent membership (represented by the chairs of the African Union and the African Union Commission, as with the European Union today).

These gatherings have the potential to put Africa on a new course. International support is crucial, but that course must be charted and led by the continent itself.

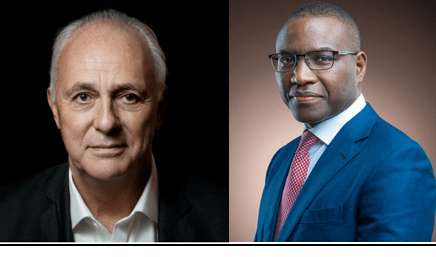

Amadou Hott is Special Envoy of the President of the African Development Bank for the Alliance for Green Infrastructure in Africa. Mark Malloch-Brown, a former deputy United Nations secretary-general and co-chair of the UN Foundation, is President of the Open Society Foundations.

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2023.

www.project-syndicate.org