1.0 Introduction

This study is an attempt to analyze the extent to which Ghana’s domestic debt restructuring options such as debt reduction, debt rescheduling and debt reprofiling will impact on the financial sector as well as on the overall economy.

For the purpose of this paper, domestic debt restructuring (DDR) refers to changes to contractual payment terms of public domestic debt (including amortization, coupons, and any contingent or other payments) to the detriment of the creditors, either through legislative/executive acts or through agreement with creditors, or both. In this paper, domestic sovereign debt (domestic debt for short) is defined as public debt liabilities that are governed by domestic law, and subject to the exclusive jurisdiction of the domestic courts of a sovereign (IMF (2013, 2015b, 2020) and Asonuma and Trebesch (2016).

This research is motivated by a number of contributions. First, the value of the paper lies in that the results provide, for the first time, evidence of the relationship domestic debt restructuring and debt reduction, debt rescheduling and debt reprofiling and its impact on the Ghanaian economy. Second, this paper contributes to the limited literature on domestic debt restructuring in developing countries in general and in Ghana in particular. The review of the literature suggests that not only there are few papers researching the issue of domestic debt restructuring but also all of them approach the issue but by describing the state of domestic debt restructuring not from debt reduction, debt rescheduling and debt reprofiling perspectives.

There had been much media attention over the past months on what domestic creditors will do in the case of Ghana’s domestic debt restructuring. It seems there will be three approaches: the government as debtor may prefer a debt reduction i.e Haircut (Debt reduction) whereas other creditors like universal banks would seem to prefer rescheduling and reprofiling with lower interest.

Ghana’s total public debt as of October 2022 was US$48. 87 billion (GHC467.4 billion or 84% of GDP) from US$32.3 billion (GHS143 billion or 55.5% of GDP) in 2017, according to Bank of Ghana and Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning data. Of this, external debt was US$28.1 billion (GHS203.4 billion or 40.5% of GDP), while domestic debt issued in cedis was US$26.3 billion (GHS190 billion or 37.8% of GDP). The current country’s debt to GDP ratio stood at about 84% which the World Bank has projected to reach 107% by the end of 2022. Ghana’s total public debt as the end of September,2022 stood at GHC 467.4 billion with the domestic debt component was GHC195.7 billion whilst external debt stood at GHC 271.7 billion. The recent increase in the domestic debt was largely due to the rising interest costs whilst the sharp in increase in the external debt was due to depreciation of cedi against all the major trading currencies. According to Minister of Finance since the beginning of 2022, the depreciation of the local currency has added GHC 93.9 billion to external debt.

Debt was an increasing problem across all poor income groups of Sub-Sahara African countries prior to COVID-19, and but the pandemic has only exacerbated the problem. In fact, African countries including Ghana has been borrowing heavily on both the domestic market as well as the global financial markets in recent years—a trend that has created new challenges in the area of debt servicing cost in the face of dwindling domestic revenue mobilization.

The two Bretton Woods institutions, the World Bank and IMF recently announced that the projected the Ghana’s Debt to GDP ratio to reach 107% and 90.7% respectively the end of December, 2022 compared to Bank of Ghana’s Debt to GDP ratio of 78.3% in July, 2022 but has increased further to GHC 467.4 billion or Debt to GDP ratio of 84% in September, 2022, Rising debt levels have corresponded with rising debt service cost, but as country such as Ghana has not necessarily improved their ability to revenue mobilization over the past such obligations.

Indeed, failure to meet debt service obligations is said to have devastating impacts, including downgrading by international credit rating agencies (and, hence, future higher costs), heightened pressure on foreign exchange reserves and domestic currency depreciation (60% depreciation against the major trading currencies), higher inflation and the real possibility of being rationed out of the market—and negative reputational consequences. According to Owusu Sarkodie, A. (2022) by time the HIPC initiative ended in 2006, Ghana’s total public debt was US$ 780 million (25% of GDP).

The public debt stock has since risen by 7000% to US$54 billion which is about 78.3% of GDP in June,2022but increased further to GHC 467.4 billion in September, 2022. In Cedi terms the country public debt has increased from GHC9 billion in 2008 to GHC 122 billion in 2016 and has increased to nearly GHC 467.4 billion in September, 2022. The current debt to GDP ratio of 84% while the average for developing countries is 60%. The total Ghanaian debt has grown over GHC 345 billion over the past six years.

According to Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning annual debt report (12/2021) the country’s domestic debt stock stood at GHC 53.4 billion in 2016 however increased to GHC 66.7 billion in 2017, but increased to GHC86.8 billion in 2018, grew further to GHC104.4 billion in 2019, also increased further to GHC149.8 billion in 2020 but grew further to GHC181.8 billion in 2021 and increased to GHC 195.7 billion in September, 2022. From the Ministry of Finance domestic debt has increased from GHC 66.7 billion in 2017 to GHC195.7 billion in September, 2022 thus showed nominal increase of GHC 129 billion over the past six years. After the HIPC initiative that ended in 2006, the Ghana public debt stock in terms of domestic and external had been driven by the continuous accumulation of budget deficits, persistent currency depreciation, unproductive borrowing for consumption and off budget borrowing and off budget borrowing. Ghanaian governments have a history of large fiscal deficits in election years.

The country’s continuous high fiscal deficit was driven partly by unproductive public spending that was not efficient in supporting equitable development (for instance, during the run-up to elections in 1992, 1996 and 2000, 2008, 2012. 2016. In 2020, the deficit was 15.2% of GDP compared to 8% average from 2017 to 2019, but still higher than the average fiscal deficit in low -income African countries of about 5% of GDP. Ghana’s extensive borrowing from the domestic and external markets and spending have not been matched by a commensurate increase in revenue. Rising public expenditures in the context of persistently weak revenue performance have undermined Ghana’s fiscal and debt sustainability in recent years.

Ghana just rakes 12.3% 0f taxes of GDP, below the African average of 16.6%. The economy’s overreliance on commodity exports mainly cocoa, gold and limited oil production made it vulnerable to external events that have caused the recent foreign currency crunches and economic downturn. Ghana has not been able to diversify its economy and the structure of the economy has remained the same in post- independence period.

Over the past decade Ghanaian public debt has also been rising again because of range of factors, from after-effects of the 2008-2009 global financial crisis, energy sector excess capacity payments GHC17 billion which related to legacy of take or pay contracts that saddled the country’s economy with annual excess capacity charges of close to US$ 1 billion between 2013 to 2016; 2017-2019 financial sector bail out which is said to have cost GHC 25 billion, persistent high budget deficits, Covid 19 pandemic and commodity pricing slowdown to low domestic savings rates and infrastructure investment promises made by democratically elected governments.

Also, corruption and financial irregularities at the Ministries, Departments and Agencies contributed to the rising public debt over the country over the past decades. The underlying causes of the rising debt are therefore, the continued dependence on commodity exports, as well as borrowers and lending not being responsible enough, meaning that new debts do not generate sufficient revenue to enable them to be repaid (Atuahene, 2022). Other causes are the sharp deterioration in terms of trade, higher interest rate changes on non-concessional loans, huge currency depreciation and low commodities prices are often mentioned as some of the major causes of rapid growth of public debt in Ghana over the past decade. Although the primary responsibility for avoiding the build-up of unsustainable debt lies with sovereign borrower such as Ghana and lenders, lenders should also lend in a way that does not undermine Ghana’s future debt sustainability. Both Ghana and lenders can be adversely affected by sovereign defaults and both are accountable for their own conduct in these transactions. Irresponsible borrowing or lending can lead to illegitimate debts which have contributed to the country’s unsustainable debt burdens (Ellmers, 2017[1]). It is a fact that Ghana’s public debt has increased astronomically over the last four to five years and the increase in the both domestic and external debt had been occasioned by unproductive borrowing, high budget deficits, and different kind of exogenous shocks that the country faced which is not unique to Ghana.

This situation has led the country using about 70% of the revenue to service debt. Ghana’s debt-service costs in the first half amounted to 20.5 billion cedis ($2 billion), equivalent to about 70% of tax revenue, according to Bloomberg (2022). Unfortunately. The cost of debt service has been rising because of the rising interest rate globally which has resulted in higher debt service costs. The last straw has been the Covid 19 pandemic has impacted negatively the debt situation in many developing countries including Ghana which both the domestic and external debt deteriorated considerably. The rising interest rate environment being fueled by the Russian and Ukrainian war has worsened debt situation in developing countries such as Ghana with the attendant rising debt service costs. To make matters worse, many developing countries including Ghana cannot reduce their debt burden on their own because they cannot generate sufficient revenue especially from their tax systems.

Ghana’s expenditure has been driven by interest expenditure as the country took a lot of expensive domestic debt and continued to borrow during the Covid 19 pandemic which meant that interest payment had been elevated now. Ghana and other countries are drifting towards a debt crisis. Economic slowdowns and rising inflation have increased demands on spending, making it almost for the country to pay back the money it owes. Ghana’s major problem now is rising public debt which stands above 84% of GDP or GHC 467.4 billion as at September, 2022 with domestic debt component of GHC195.7 billion but the overall Debt to GDP ratio is projected to reach 107% by the end of 2022, according to World Bank whilst IMF has predicted 90.7%. Ghana has been thrust into debt distress as 70% of its total revenue go towards debt servicing. Restructuring of domestic debt leads to an effective default ending the ‘gilt’ status of government bonds. From the above the restructuring of the country’s public debt has become the necessary option if the country to seek bailout from the Bretton Woods institutions requires that the debt should be brought to sustainable level.

The only option would be to restructure both its external debt as well as the huge and expensive domestic debt. Also, the persistent depreciation of the local currency against the US $ has contributed the unsustainable debt levels It can be concluded that Ghana’s debt levels are unsustainable, the country will have to take steps to restructure its debt to qualify for IMF assistance. The Fund states that it won’t lend to countries that have unsustainable debts unless the member takes steps to restore debt sustainability, which can include debt restructuring. From above Ghana must restructure its local currency debt as part of it’s plan to secure a US$ 3 billion loan from the International Monetary Fund. The country’s largest domestic debt holders include domestic banks, Bank of Ghana, non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs), private individuals, pension funds, insurance companies and foreign investors which must be engaged in debt restructuring that could entail debt reduction, debt rescheduling and debt reprofiling.

Ghana’s domestic debt restructuring could lower the wealth and income of individual households, directly through retail holdings or indirectly through shares in mutual funds and pension funds. In addition, domestic debt restructuring may affect availability of bank credit and cost of borrowing for Ghanaian companies and households with potential indirect distributional effects. The bondholders’ losses from debt reduction, debt rescheduling and debt profiling could affect domestic banks and businesses from expanding, thus decreasing output. When output decreases, jobs will not be created and they cannot make profit and that will also affect the government’s ability to generate enough revenue through taxation to service its debt service obligations. The restructuring of domestic debt would be part of the Ghana’s debt sustainability plan required by the International Monetary Fund.

The country’s debt restructuring should focus on domestic bonds, though external debt could be included depending on how much Ghana would have to reduce its debt servicing costs to achieve fiscal sustainability. The only two instances of domestic debt restructuring in Ghana, in 1979 and 1982, primarily featured demonetization rather than principal haircuts or interest rate reduction (Imani Center Policy ,2022). From the data analysis of 10% Haircut of the total PV of Bond value of Domestic banks, Bank of Ghana, Firms and Institutions, and Individuals of GHC344,403,752,859 recorded a total loss of GHC33,913,361,127 compared to the data analysis of Rescheduling options where the Mark to Market of coupon rate of 26% from to 10% coupon rate with extended tenure from 5 years to 10 years which recorded losses of GHC 55,272,093,147 to the various bondholders.

From the data analysis of Rescheduling option where the Mark to Market of coupon rate drop from 26% to 10% with extended tenure from 5 to 10yrs with coupon payable over the 10year period also recorded bond value losses of GHC 108,446, 402,471 compared to the analysis of the Debt Reprofiling data indicates that the maturity extension at the prevailing rate of 26% for another five years domestic investor can loss a total of GHC 108,446,402,294 over the extended period. The data analysis clearly shows that domestic investors could incur substantial losses in the debt restructuring

When considering the restructuring of domestic debt, a government usually only has three broad strategies as follows:

- Shaving off some of the principal amount (“face value reduction” or “haircut”).

- Changing the tenor or maturity of the debt, which is to say deferring payments.

- Lowering the initial interest rate of the debt instruments.

With government securities constituting nearly 30% of assets, and exceeding 45% of income (due to the high concentration of “investment” funds in government securities among Ghanaian banks), any process that cuts face value(“haircuts”) will hit the risk-weighting of banks’ capital. Similarly, any process that touches coupons/interest rate will hit the bottom-line (profit after tax) of banks massively. The analysis of the study showed that the possible effects on financial sector, job losses, output losses, general health of the economy and loss of confidence in domestic investment.

However, negative relationship was identified between financial threat and total debt, stress, economic hardship and anxiety. Findings from this study imply that job loss, output loss, general health, information search and loss of investment are major factors that determined financial threat in Ghana. Moody’s downgrade of Ghana’s long term issuer ratings to Ca from Caa2 or further junk status on 30th November 2022 confirmed that creditors will likely incur substantial losses in the restructuring of both local and foreign bond holders and this thus confirmed the above analysis.

2.0 Ghana’s public debt dynamics

For the purpose of this paper, Ghana’s domestic debt restructuring (DDR) refers to changes to contractual payment terms of public domestic debt (including amortization, coupons, and any contingent or other payments) to the detriment of the creditors, either through legislative/executive acts or through agreement with creditors, or both. The government has been engaging the country’s largest debt investors including local banks, firms and institutions, insurance companies, pension funds and private individuals in the domestic debt restructuring project that could entail extension of maturities, reduction in the coupon rates, haircuts on principal and interest payments.

A country’s debt dynamics includes both external and domestic debt, and debt accruing to state-owned enterprises and its maturity structure. All need to be considered when considering any debt restructuring. Ghana’s total public debt as of September, 2022 was US$48. 7 billion (GHC467.7 billion or 84% of GDP) from US$32.3 billion (GHS143 billion or 55.5% of GDP) in 2017, according to Bank of Ghana and Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning data. Of this, external debt was US$28.1 billion (GHS203.4 billion or 40.5% of GDP), while domestic debt issued in cedis was US$26.3 billion (GHS190 billion or 37.8% of GDP). The country’s debt to GDP ratio stood at about 84% (GHC467.4 billion with the domestic debt component stood at GHC195.7 billion with the external debt component reaching GHC 271.5 billion as at September,2022 of which the World Bank has projected to reach 107% by the end of 2022. Ghana has been thrust into debt distress as about 70% of its total revenue goes into debt servicing obligations thus leaving little room for other statutory obligations or investment in infrastructure.

The country’s debt reorganization will initially focus on domestic bonds, though external liabilities could also be included depending on how much Ghana would have to reduce its debt-servicing costs to achieve fiscal sustainability. Regarding external debt, the portfolio includes debt owed to multilaterals such as the IMF and World Bank, bilateral, commercial loans such as Eurobonds, and other export credits. The external debt also comprises of fixed (86.5%), variable (13.1%) rate and some interest-free (0.4%) debt. As of 2021, about 72% of the external debt was also dollar-denominated.

Based on the monthly bulletin published by the Central Securities Depository for September 2022, the total treasury bills and bonds issued by government stood at GHC 160.1bn. Banks were the largest holders with 31.6% (GHC50.6 billion), Firms & Institutions with 25.3% (GHC 40.5 billion), Others (including retail and individuals) with 13.9% (GHC 22.3 billion), Foreign Investors with 10.8% (GHC 17.3 billion), Bank of Ghana with 10% (GHC 16.01 billion), Pension funds with 5.6% (GHC 8.9 billion), Rural Banks with 1.4% (GHC 2.2 billion), Insurance Companies with 0.9%(GHC 1.44billion) and SSNIT with 0.4% (GHC0.6billion) .

Treasury Bills represented 16.4%(GHC26.25billion) of total securities, medium tenor bonds (2yrs to 5yrs) are 49.5% and long tenor bonds (6yrs and above) are 34.2%. Foreign investors hold 10. 8% (GHC 17.3 billion). The currency denomination of the domestic debt should not influence the inclusion or exclusion of certain securities from the restructuring. Including both local and foreign currency debt issued under domestic law in the restructuring will set ex ante equal conditions for both types of instruments and allow to achieve greater savings (e.g., Jamaica, 2010 and 2013).

For a highly dollarized economy, where the share of local currency debt is very small, there may be a case for excluding local debt from the restructuring, for example when those instruments are important for the operation of the domestic payments system and development of the local currency bond market (e.g., Uruguay, 2003 and Argentina, 2019).

The domestic debt of GHC160.1 billion excludes the Government treasury bills valued approximately GHC 26.25 billion which is not included in the perimeter of domestic debt restructuring.

According to IMF report (2021) including Treasury bills in the restructuring carries risks, but may be unavoidable in some cases, from these reasons Ghana government has excluded Treasury bills from the domestic debt restructuring. Changing the terms of Treasury bills can have adverse effects on interbank liquidity, the central bank’s ability to conduct monetary policy operations, and the country’s capacity to manage its short-term payments. That said, when the share of Treasury bills in domestic debt is high, the sovereign may have no alternative but to include them in a debt restructuring (e.g., Barbados, 2018 and Russia, 2000) so as to reduce its short-term financing needs and rollover risk.

Where Treasury bills do not create large refinancing pressures, it is generally advisable to exclude them from the domestic debt restructuring. Domestic debt investors have already lost 52% of the USD value of their holdings this year and the government needs to weigh the fact that it needs access to the domestic bond market to finance the budget over the next three years in any decision on domestic debt restructuring. Debt restructuring can be done either via tenor extension, coupon reduction, reprofiling, principal haircut, or a combination of three or all options. With the USD value of domestic debt having been depreciated away, government’s focus should be on coupon reduction, combined with tenor extension if required, to reduce the interest cost of domestic debt.

By the IMF computation public domestic debt may include the debt of some of the State -Owned Enterprises (SOEs) and the outstanding of contractor arrears of GHC 10 billion as at September 2022 has to be factored in the public sector debt possibly excluding interests on the outstanding payment (Cherry, 2022)’ Ghana’s current unsustainable has led to high debt distress where the country will be unable to fulfill its financial obligations and debt restructuring will be required. Over the past six months, Ghana’s economy has experienced higher inflation which has been on a sustained upward trajectory. The rising inflation with the subsequent increases in Bank of Ghana’s policy rate have resulted in a rising interest rate environment.

The Cedi has persistent suffered a very high levels of depreciation. According to Bloomberg the Cedi has lost about 60% 0f its value against the US$ this year, making it the second worst performing currency in the world after the Sri Lankan Rupees. The country has been burdened by unwieldly food and fuel costs which weigh unevenly which has been prone to protest and political chaos. This has resulted in the value of existing government bonds declining. This means that the value of Ghana government bonds has been declining. However, the downgrade by the rating agencies have caused the country to lose access which has caused the steep depreciation of Cedi against the major trading currencies since March 2022 and also suffered higher borrowing costs in the domestic market and in addition harmed growth and investment.

Restructuring only domestic law debt may also offer a way of ringfencing the external reputational consequences of debt restructuring and avoiding loss of access to external debt markets. But at the same time, Ghana’s domestic debt restructuring may impose losses on domestic stakeholders and may have large direct and indirect costs for the domestic financial system, with spillovers to the domestic economy.

3.0 Theoretical framework for debt restructuring

Several studies were conducted to identify the best way to restructure public debt (reduction in the face value, or lengthening of maturities). A restructuring process can be considered useful because it provides relief for the debtor country, and gains fiscal space for structural reform (i.e. reduces a debt overhang problem). In a 1988 study, Krugman compares two strategies that can be adopted by a creditor country: providing new lending (at a lower interest rate) or a reduction in the face value (a ‘haircut’). The best option is identified according to debtor conditions, in order to provide the right incentive to repay – and not to write-down (i.e. reduction of value) creditors’ claims unnecessarily.

Reinhart and Trebesch focused on restructurings in the 1980-1990s, as well as in the post-World War I period (1920-1930s) in their 2015 study. Comparing a ‘haircut’ process (i.e. the Brady Plan and the generalized default of 1934) with measures lengthening maturities (i.e. the 1931 Hoover moratorium and the 1986 Baker plan), they illustrate that ‘haircut’ interventions produce benefits in term of GDP growth rate for the debtor countries.

Continuing the focus on growth, Forni et al. (2016) studied the effects of restructuring procedures between 1970 and 2010. Their 2016 study divides ‘bad’ and ‘good’ restructurings (i.e. ‘restructurings that allow countries to exit a default spell’ and with a low level of debt). In general, they observe that following a restructuring episode, debtor country’s growth rates decline, except in cases of ‘good’ restructurings, associated with increasing growth. There are three options of debt operations in a debt restructuring: debt rescheduling—lengthening of debt maturities and/or reducing the coupon rate, while keeping the face value of debt the same; and debt reduction—a reduction in the nominal face value of old instruments and debt reprofiling can also connotes a transaction in which maturities are extended but there is no principal haircut and typically not even an adjustment to the coupon.

Several studies were conducted to identify the best way to restructure public debt (reduction in the face value, or lengthening of maturities). A restructuring process can be considered useful because it provides relief for the debtor country, and gains fiscal space for structural reform (i.e. reduces a debt overhang problem). In a 1988 study, Krugman compares two strategies that can be adopted by a creditor country: providing new lending (at a lower interest rate) or a reduction in the face value (a ‘haircut’). The best option is identified according to debtor conditions, in order to provide the right incentive to repay – and not to write-down (i.e. reduction of value) creditors’ claims unnecessarily. Reinhart and Trebesch focused on restructurings in the 1980-1990s, as well as in the post-World War I period (1920-1930s) in their 2015 study. Comparing a ‘haircut’ process (i.e. the Brady Plan and the generalized default of 1934) with measures lengthening maturities (i.e. the 1931 Ho over moratorium and the 1986 Baker plan), they illustrate that ‘haircut’ interventions produce benefits in term of GDP growth rate for the debtor countries.

Continuing the focus on growth, Forni et al. studied the effects of restructuring procedures between 1970 and 2010. Their 2016 study divides ‘bad’ and ‘good’ restructurings (i.e. ‘restructurings that allow countries to exit a default spell’ and with a low level of debt). In general, they observe that following a restructuring episode, debtor country’s growth rates decline, except in cases of ‘good’ restructurings, associated with increasing growth. A new theoretical model was provided by Picarelli in 2016, comparing strategies between ‘haircuts’, lengthening of maturities, and conditional additional lending. This model provides the best options available for both creditor countries (in a debt repayment perspective) and debtor countries (in a growth perspective).

Debt restructuring is now defined as an event in which a debtor is in financial difficulty and a creditor grants a concession to the debtor in accordance with a mutual agreement or court judgment. Under the old standard, ‘debt restructuring’ included all arrangements that resulted in modifications of the terms of a debt obligation (Deloitte 2006, pp. 21). The new standard requires the assets or equity interests received or surrendered by the debtor or the creditor are to be measured at fair value. The resulting gains or losses shall be recognized in profit or loss. Under the old standard fair value was not used and debt restructuring gains and losses were transferred to the capital reserve. Sovereign debt restructuring is an exchange of outstanding government debt, such as bonds or gilt- edged securities, for new debt products or cash through a legal process (Das, Papaioannou and Trebesch 2012).

To constitute a debt restructuring, one or both of the two following types of exchange must take place: debt rescheduling, which involves extending contractual payments into the future and, possibly, lowering interest rates on those payments; and debt reduction, which involves reducing the nominal value of outstanding debt. Restructurings often occur after a default, but it is also possible to conduct an early debt restructuring that pre-empts default. In addition to economic variables, the type, timing and terms of a debt exchange are largely determined by negotiations between the sovereign debtor and its creditors. Domestic-law defaults are a global phenomenon. Over time, they have become larger and more frequent than foreign-law defaults. Domestic-law debt restructurings proceed faster than foreign ones, often through extensions of maturities and amendments to the coupon structure.

While face value reductions are rare, net-present-value losses for creditors are still large domestic debt restructuring (DDR) refers to changes to contractual payment terms of public domestic debt (including amortization, coupons, and any contingent or other payments) to the detriment of the creditors, either through legislative/executive acts or through agreement with creditors (IMF,2021) Sovereign debt markets in emerging economies have experienced radical transformations in recent decades. As many sovereigns began to tap international capital markets, bonds replaced bank loans, and increasingly perfected clauses were added to bonds to facilitate debt restructuring (Buchheit et al., 2019; IMF, 2020). Another critical, yet less discussed, change is the increased relevance of domestic debt markets (Gelpern and Panizza, 2021; Reinhart andRogo_, 2008). Traditionally, domestic debt markets for emerging sovereigns were either non-existing or closed to foreigners (CGFS, 2007).

Emerging sovereigns could only borrow from foreign investors in foreign currencies and international markets (Eichengreen and Panizza,2005). Since the 90s, as a result of financial deepening and economic growth, governments are increasingly relying on domestic borrowings to fund their _financing needs (Gelpern and Setser, 2004; Burger and Warnock, 2006; IMF, 2020). The definition of domestic public debt, grounded on whether government debt is governed by the domestic law, highlights a dimension that crucially shapes the restructuring process: debt jurisdiction (Gelpern and Panizza, 2021; IMF, 2021).

Domestic sovereign debt (domestic debt for short) is defined as public debt liabilities that are governed by domestic law, and subject to the exclusive jurisdiction of the domestic courts of a sovereign. While the residence of investors and the currency denomination have implications for the macroeconomic consequences of sovereign default, the jurisdiction directly affect governments’ ability to restructure debt. As described in Chamon et al. (2018) or IMF (2020, 2021), the terms of government debt issued in the domestic jurisdiction can be more easily restructured using legislative or executive measures, with repercussions for market access. Moreover, domestic sovereign debt markets are the backbone of domestic financial systems. According to CGFS (2007), domestic bond markets promote financial stability not only by reducing currency mismatches but also by creating a benchmark (market-determined) yield curve that reflects the costs of borrowing domestically at different maturities. In emerging economies such as Ghana lacking well-functioning domestic debt markets, banks may _find it hard to price and provide long-term lending.

As a result, restructuring upon domestic-law debt may affect the financial standing of the private sector over and beyond what a default of debt governed under foreign laws may do (Gelpern and Panizza, 2021; IMF, 2021). In fact, as the consequences of sovereign default are increasingly borne domestically, government incentives to default have likely changed. While governments defaulting externally are concerned about being excluded from international capital markets, those defaulting domestically are more concerned with the loss of domestic investment and its impact on the domestic economy

4.0. Theoretical argument on domestic versus external debt restructurings

Emerging and some developing countries are facing with growing debt challenges after the Covid 19 pandemic and such countries will have to restructure their debt but restructurings will raise complex issues for both external and domestic debt. On the domestic side, there will be difficult trade-offs between the need to restructure sovereign debt owed to domestic banks, in some cases, and the impact of those restructurings on financial stability and domestic banks ability to finance growth. On the external side, increased diversity in creditor composition raises important coordination challenges. Some of the emerging and developing countries used to borrow mainly from Paris Club official bilateral creditors and private banks, alongside multilateral institutions. Paris Club creditors and Eurobond markets had strong coordination mechanisms, including through a shared understanding on how the two creditor groups interacted.

According to IMF (Policy Paper No. 2021/071) posited that the key to determining whether or not domestic debt should be part of a sovereign restructuring is weighing the benefits of the lower debt burden against the fiscal and broader economic costs of achieving that debt relief. The fiscal costs may have to be incurred in the context of restructuring because of the need to maintain financial stability, to ensure the functioning of the central bank, or to replenish pension savings. A sovereign domestic debt restructuring should be designed to anticipate, minimize, and manage its impact on the domestic economy and financial system. Debt restructurings in Ghana will raise complex issues for both external and domestic debt.

Ghana has experienced a deepening of sovereign-bank links, with larger holdings of domestic sovereign debt at domestic banks. On the external side, increased diversity in creditor composition raises important coordination challenges. On the domestic side, there will be difficult trade-offs between the need to restructure sovereign debt owed to domestic banks, in some cases, and the impact of those restructurings on financial stability and domestic banks ability to finance growth. Recent case studies show that the negotiation process and the basic restructuring mechanics are very similar when comparing domestic debt restructurings to external debt restructurings ( Erce and Diaz-Cassou, 2010, and Sturzenegger and Zettelmeyer, 2006). However, there are also important differences. One difference is that domestic debt is adjudicated domestically, often leaving litigation in domestic courts as the only recourse available to investors.

A second difference is that investors in domestic instruments are normally mostly local residents (i.e., domestic banks, insurance companies, and pension funds), in which case a restructuring of domestic debt instruments will directly affect the balance sheets of domestic financial institutions and can affect the country’s overall financial stability. Furthermore, exchange rate considerations and currency mismatches play a lesser role in domestic debt than in external debt restructurings. Another difference is the duration of renegotiations. Since 1998, domestic debt restructurings were implemented in less time than external debt restructurings. Argentina’s domestic debt was restructured in November 2001, while the external bond exchange took four more years. Russia’s domestic GKO bonds were restructured within six months (between August 1998 and March 1999), while the restructuring of external bank loans took until 2000 to complete.

In Ukraine, the domestic debt exchange was implemented in less than two months, with separate offers for resident and non-resident holders ( Sturzenegger and Zettelmeyer (2006) for details). In Jamaica, the restructuring of a sizable stock of domestically issued debt took about two months. In addition, there have been instances of differential treatment of domestic versus external debt during restructurings. In Belize (2007), the government restructured only the external bonds. In Ecuador (1998–2000), the authorities restructured both short- and long-term bonds held by nonresidents, but not medium- and long-term domestic debt. In a similar vein, Ecuador’s (2008– 2009) default and debt buyback only affected two outstanding international bonds, but no domestic debt. The Jamaica (2010) restructuring is the opposite case, where externally issued Eurobonds were excluded from the restructuring.

From literature, 68 episodes of outright de jure domestic debt default and domestic restructuring documented by Reinhart and Rogoff (2011c), a range of mechanisms was used: forcible conversions; lower coupon rates (for example, China and Greece in the 1920s and 1930s); unilateral reduction of principal, sometimes in conjunction with a currency conversion (for example, Ghana in the 1970s and 1980s; Austria, Germany, and Japan in the 1940s and 1950s), and suspensions of payments (for example, Bolivia in the 1920s, Peru and Mexico in the 1930s, and Panama in the 1980s).

5.0 Theoretical review of domestic debt

Domestic debt refers to that portion of country’s public debt borrowed from within the confines of the country. These borrowing are usually obtained from central bank, deposit money banks, discount house, non-bank financial institutions, corporate bodies and individuals. Domestic debt consists of government borrowing from within the domestic economy. This type of debt, unlike the external debt does not increase the total resources available to the country. There is simply a transfer of resources from one end to the other public services purpose (Nuredeen & Usman, 2010)[2]. Also, the interest payment only transfers resources from the tax payers to the bondholders. Domestic debt only effects a transfer of purchasing power among the citizenry of the country, thus there is no giving up of real output to another country. Instruments used for domestic debt include treasury bills, bonds, treasury certificates and others.

The government borrows from domestic market to finance budget as well as financing capital projects. The oppressive burden of expensive domestic debt has fostered the initiative by various governments to borrow externally at the cheaper rate of interest. For example, in 2018, the government of Ghana through the Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning borrowed US$500 million from Global Depositary Notes (GDN) to refinance expensive domestic cedi denominated debt. The advantage of issuing domestic currency debt is that it can serve as an effective strategy for the country to reduce its vulnerability to exchange rate valuation effects caused by excessive capital inflows followed by sudden outflows and capital reversals.

Debt denominated in the local currency also increases the policy space because it allows the monetary authority such as Bank of Ghana counter external shocks such as commodity price shocks (cocoa and oil) or slowdown in world demand through exchange rate depreciations without bringing about a sudden jump in the debt/GDP ratios, and possibly, debt crisis (IFS, Working paper no 3/2015)[3]. However, issuance of domestic debt does have its drawbacks, as it is costly to obtain because government will have to offer higher interest rates on domestic bonds and bills relatively compared to external bonds issued in the global market. Furthermore, domestic debt increases the exposure to refinancing risk owing to its short-term maturity. Finally, the secondary market for domestic bonds has not been properly developed.

As various governments from developing countries including Ghana decide to borrow excessively from the domestic markets to finance its budget deficits, they would compete with local companies thereby crowding them out on the domestic market thus leaving little funds for private sector development. Patenio and Agustina (2007)[4] opine that reduction in a country’s capacity to service its debt obligation as a resulting from crowding out effect could leave a little capital for domestic investment thus affecting the economic growth and development. On the domestic front, the consequences of such a huge and growing domestic debt are that, first, a sizable portion of government revenue will be channeled to servicing the debt; and second, the likely increase in interest rates will lead to high cost of borrowing by the private sector which will crowd-out private sector investment (AFRODAD, 2011)[5].

Also, investor confidence in the country could be dampened by the deteriorating debt-GDP ratio as increased borrowing may further deter international investment and hinder private sector growth (IMF Country report, 2013)[6]. Excessive domestic debt affects the interest rates and interest rate structure. When the government borrows from the domestic market, there emerges a fund crisis (due to excess demand) which raises interest rates. The interest rate is an important determinant in investment decisions, so high interest rates reduce profit margins and deter investment especially since retained earnings are an important source of finance.

The second impact is through taxation. Debt has to be paid and the economy has to generate the revenues to service debt through taxation. A high debt burden sends signals on the magnitude of government liability and thus the taxation expectations for debt service. High taxes are a disincentive to investment. Lastly, domestic debt cannot be defaulted, unlike external debt. This is because domestic debt is mostly held by the banking sector and default may trigger a banking crisis. Hence, rising domestic debt levels increases default risk in the financial sector players who in turn increase interest rate levels on funds loaned to the private sector.

5.COMPARABLE APPROACHES OF PUBLIC DOMESTIC DEBT RESTRUCTURING: (DEBT REDUCTION; DEBT RESHEDULING AND DEBT REPROFILING}

There had been much media attention over the past months on what domestic creditors will do in the case of Ghana’s domestic debt restructuring. It seems there will be three approaches: the government as debtor may prefer a debt reduction i.e Haircut (Debt reduction) whereas other creditors like universal banks would seem to prefer rescheduling and reprofiling with lower interest. Grossman & Van Huyck (1988) explained the variation of Haircut across debt restructuring episodes that countries that have suffered very severe shocks including wars, armed conflicts, coup detat, output collapses, declines in terms of trade suffered from higher Haircuts than countries that have not faced these major disturbances but poor countries with larger debt burdens such as Ghana may also experience larger Haircuts.

There is the countervailing effect of debt reduction. First, countries imposing high Haircut will reduce their indebtedness more significantly, making them more solvent at least in short run. Second, high haircut could be seen as a signal of untrustworthy economic policies and expropriative practices by the government, with adverse consequences for country spreads and capital market access (Cole and Kehoe.1998). Finally, it is possible that countries like Argentina in 2005 (75%); Greece in 2012 (64%) that imposed higher haircuts were in a worst shape than those countries imposing lower haircuts like Uruguay in 2003 (13%).

5i. In debt restructuring, a haircut is the reduction of outstanding interest payment or a portion of a bond payable that will not be repaid or both the portion outstanding interest payment and bond are reduced. In general, is a “haircut” better than both debt rescheduling with lower interest rates and debt reprofiling?”

Haircuts are computed as the percentage difference between the present values of old and new instruments, discounted at the yield prevailing immediately after the exchange. Federico Sturzenegger and Jeromin Zettelmeyer(20051 )found average haircuts ranging from 13 percent (Uruguay external exchange) to 73 percent (2005 Argentina exchange).

First, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) noted in its recent debt sustainability analysis on Ghana that next steps should include, “at least (i) the changes in nominal debt service over the IMF program period; (ii) where applicable, the debt reduction in net present value terms; and (iii) the extension of the duration of the treated claims.” Wang and Qian (2022) opined that one need to understand what “net present value (NPV) terms” means, we conducted an exercise using the IMF’s definition of NPV for debt. We calculated the NPV of “forgiving x percent of debt,” and then the NPV of “extending the loan from ten years to 20 years at a lower interest rate of y percent.” In the third step, we equalized the former (aka NPV1) to the latter (aka NPV2), finding the solution for x (percent of forgiveness) and y (percent of interest rate on the loan). For every value of x, there is a y which equalizes the NPV1 and NPV2. For instance, a forgiveness of 39.4 percent would have the same NPV of an extension of ten additional years at a reduced interest rate from 6 percent to 2 percent.

A forgiveness of 28.76 percent would be equivalent to an extension of ten additional years at a reduced interest rate from 6 percent to 4 percent. In this way, the gains for the debtor country should be equal in the two options and creditors can find an “equitable treatment” for their different approaches

In fact,” Haircuts”: “Rescheduling” and “Reprofiling” have been used in meeting specific needs of debtors and creditors for distressed resolution exercises. This has been the case for the Paris Club throughout the years and it was also the case for the Brady Plan in early 1990s. Debt sustainability means helping debtor countries acquire sufficient cushion to serve the debt every year throughout the life of the debt. This can be achieved through haircuts, rescheduling, reprofiling as well as the natural hedge through structured finance solutions to mitigate the volatility of net cash flow brought by the boom-bust cycles.

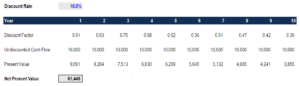

The natural hedge can be achieved through the use of commodity-price-linked bonds or other forms of state-contingent debt instruments. In Table 1, we provide the detailed calculation comparing two options of debt restructuring on a $100 million loan with a discount rate of 10 percent, where contract interest initially was 6 percent, finding solutions for x and y by equalizing NPV1 to NPV2. The NPVs in the last column represent the benefits obtained by debtor countries in the future, discounted to the present value.

The present value of the debt is the stream of future debt service payments, discounted for the time value of money. The idea underlying the present value calculation is the money paid today is more burdensome than money paid in the future because of the opportunity cost and inflation. The general formula for calculating the present value of payment streams; Example showing how to calculate NPV. You expect a 10% (0.10) return of GHC10000 on your total investment each year. To calculate the NPV of your cash flow (earnings) at the end of year one (so t = 1), divide the year one earnings (GHC1001) by 1 plus the return (0.10). NPV = Rt/(1 + i)t = GHC100001/(1+1.10)1 = GHC9091. Where PV= Present Value of the streams of Future payments. C= Debt service payment in time period (n). rate =Discount rate (10%). The Bretton Wood Institutions refers to Present value of Debt as Net Present Value (NPV)

Debt restructuring could affect a country’s prospects in at least two alternative ways. Default involving higher haircuts/restructurings may entail more severe reputational costs. On the other hand, the channel of debt relief operates in the opposite direction. Since higher haircuts reduce the level of government’s debt more substantially, such debt reduction may allow Ghana to exit a debt overhang improving in this way economic prospects.

Note: These calculations are based on a $100 million loan at a consistent discount rate of 10 percent. For each row, Option 1 and Option 2 are equal in NPV terms, implying that debtor countries gained the same amount in NPV terms. Source: Authors’ Wang and Qian (2022) adopted for this paper’

5ii. IMF (1983) stated that there is nothing mysterious about debt rescheduling as its amounts to a rearrangement or restructuring, generally involving a stretching out, of the original repayment schedule with respect to a particular debt or a set of debts. Rescheduling is one of the options available to Ghana that is having difficulties in “servicing” it’s domestic debt, that is, in making the repayments of principal and interest as they fall due. One option left for Ghana government is to reschedule the terms of existing bond issues. This usually involves lengthening the maturity structure and lowering the interest cost or reduction of the coupon rate.

Ghana has run into debt servicing difficulties for a number of reasons: (1) as it has borrowed excessively in the domestic market, that is, beyond its current capacity to service the debt; (2) it might have borrowed on unfavorable terms (for example, it may have accumulated too much short-term debt) or it may have built up an unfavorable maturity profile, with a “hump” in repayments falling due; (3) it may be affected adversely by events that it cannot control. Also, for reasons beyond its control, the country may experience a temporary but substantial revenue shortfall reducing its tax earnings and its ability to service its debt. A rescheduling may cover the principal only or the principal and interest on repayments falling due in a particular period (generally one year).

The rescheduled debt may include a “grace” period and a “stretched” repayment schedule. For instance, if repayments falling due in 2023 amount to GHC1000 million and the country succeeds in arranging a rescheduling with a grace period of three years and a repayment period of five years, this means that the repayment falling due in 2023 will be made during the years 2026-2030. Rescheduling thus is not merely postponing a debt: it is spreading over a number of years payments that were due in one year. There is, of course, a cost involved, in that the debtor country must pay interest on the amount outstanding until the debt has been finally and fully repaid. The rationale for a rescheduling is to provide time for Ghana government: in cases where the debt problem is due to a temporary tax shortfall; in cases where the problem is more fundamental, rescheduling lightens the country’s debt burden and gives time for appropriate corrective measures to be taken in order to improve the domestic resource mobilization.

In this latter case it is important to recognize that rescheduling is not a panacea and cannot work in isolation: it can only succeed if it is accompanied by steps to address the underlying economic problems. Ghana government be a major debtor in the debt domestic restructuring and domestic creditors often have an implicit option to extend debt maturity as the debt approaches financial distress. This implicit “extension option” is associated with possibility for Ghanaian government and the domestic creditors to renegotiate the debt contract in the hope that the domestic debt maturity period will be extended. In general, when country’s debt is downgraded by the international credit rating agencies like Standards and Poor’s, Moody’s and Fitch’s is triggered by the “worthless debt” condition the value of the debt maturity extension is much higher than when debt default is triggered by a liquidity shortage.

The option to negotiate debt maturity is of interest to the government as by extending the debt maturity can decrease debt value even without reducing the coupon payment, i.e without giving up part of tax shield associated with coupon payment maturity that may allow the Ghana government to overcome temporary liquidity and solvency problems. This debt maturity extension would have been in line with G20 Debt Service Suspension Framework (2020) where debt relief in the form of debt maturity extensions: interest reductions rather than face value reduction (Haircut).

5iii. Debt reprofiling” — a relatively light form of domestic debt restructuring in which the tenor of a government’s liabilities will be extended in maturity, but coupons and principal are not cut. One restructuring technique that has received recent attention involve a “reprofiling” of maturities (that is, a relatively short extension of the maturity dates of affected debt instruments), often with interest rates left untouched during the extension period. The classic example is Uruguay’s debt restructuring of 2003. The IMF (2003) proposed a new tool in the global financial architecture for managing sovereign debt crisis: “reprofiling.” Reprofiling is a particular type of debt restructuring focused on extending the maturity of short-dated liabilities — applied to a single bond, this might be typified by the exchange of a two-year fixed rate government bond for a new five-year bond, a three-year extension of maturity.

This is a very useful idea as there are circumstances where an extension of maturities may allow an optimal outcome for both Ghana and domestic and external creditors; breathing space from principal maturities may allow a government to get its financial house in order and thus regain the ability to repay creditors in full. Debt re-profiling need to be studied as a subset of the general category of transactions known as debt restructurings — transactions where debt payments are reduced or delayed because of the unwillingness or inability of the issuer to pay. It is possible, of course, to mix and match these techniques (for example, a maturity extension with a coupon adjustment) and this is indeed the norm in most sovereign debt restructuring packages. For their part, creditors can be expected to express strong views about the method chosen to address a sovereign’s debt problem.

Principal haircuts are particularly disfavored by domestic creditors. When the restructuring involves only a maturity extension and/or a coupon adjustment, a post-closing improvement in the sovereign’s financial prospects and credit rating will directly benefit creditors because the secondary market value of the entire principal amount of their claims against the country will increase. Principal haircuts, however, involve a forfeiture by the creditor of portion of that claim. A subsequent improvement in the credit rating of the country can therefore lift the value of only the residual principal amount of the claim. This explains why transactions calling for principal haircuts are more likely to involve the issuance of some form of “value recovery instrument” that will permit creditors to recoup a portion of their loss if the economic fortunes of the sovereign debtor improve in the future.

One restructuring technique that has received recent attention involves a “reprofiling” of maturities (that is, a relatively short extension of the maturity dates of affected debt instruments), often with interest rates left untouched during the extension period. The classic example is Uruguay’s debt restructuring of 2003. Uruguay extended the maturity date of each of its 18 bonds issued in the international markets by a uniform five years, while leaving the coupon rates during this extension period the same as those on the bonds as originally issued. In 2016, the IMF endorsed the use of a reprofiling technique in situations where the Fund is providing exceptional access to its financing, and cannot determine with high probability whether the sovereign’s debt is sustainable. The reprofiling shifts the maturities of existing debts out of the IMF’s program period, thus obviating the need to fund those maturities with official sector resources The reprofiling shifts the maturities of existing.

Debt reprofiling would be mandated as a condition of an IMF loan under the proposed new lending policy when (IMF 2014b, 23-24): the member country seeks a large amount of funds relative to its quota (“exceptional access). The IMF suggests that reprofiling should be a comprehensive tool through which private sector creditors and official bilateral lenders move out the maturity of short-dated debt in a comparable fashion. Both the international and domestic debt of issuers would typically be included. The IMF staff’s 2013 proposal to reprofile (i.e., stretch out for a short period without haircutting principal or interest) the maturing debt of a country that has lost market access is a sensible policy in cases where the IMF is uncertain whether the country’s debt stock is sustainable. Maturity extension is the most frequent form of restructuring. Amendments to the coupon structure are also frequent, while face value reductions are relatively rare according to various empirical literature.

There have been three incidences of sovereign debt restructuring involving private creditors under IMF-supported programs since 2015. In 2015, Grenada was in default and completed a restructuring of bonds issued as part of its 2005 restructuring. The restructuring involved principal haircut and 5-year maturity extension. Two countries also restructured their debt held by private creditors as part of pre-default debt operations in 2015-16. In 2015, Ukraine restructured its sovereign and sovereign-guaranteed Eurobonds, City of Kyiv Eurobonds and sovereign-guaranteed state- owned enterprise (SOE) external commercial loans, with terms involving principal haircuts and maturity extensions on most of the restructured debt. In addition, selected non-guaranteed SOE external liabilities were also restructured, with terms involving only maturity extensions. In April 2016, Mozambique swapped existing Eurobonds with new bonds that carry higher interest rates and mature three years later than the original bonds. Domestic-law debt restructurings proceed faster than foreign ones, often through extensions of maturities and amendments to the coupon structure. Ghana may restructure it’s domestic debt may be seeking the combination of all following options: debt reduction, maturity extensions and coupon adjustments, or Debt Re-profiling.

6.0 The objective of the Ghana’s domestic and external debt restructuring framework

Sovereign debt restructuring can be pre-emptive or post-default. A default is inherently costly as it can result in a sustained loss of access to capital markets. That leaves pre-emptive restructuring when a country deems itself unable to service outstanding debt. Ghana is considering pre-emptive debt restructuring. The objective of the Ghana’s debt restructuring framework will be to identify the type of restructuring that will restore public debt sustainability while minimizing potential economic costs and financial system disruptions. Sovereign debt restructuring can be pre-emptive or post-default. A default is inherently costly as it can result in a sustained loss of access to capital markets.

That leaves pre-emptive restructuring when a country deems itself unable to service outstanding debt. The complex creditor landscape of today though makes governments reluctant to entertain sovereign debt restructuring. The landscape of sovereign borrowing has evolved from a small group made up of multilateral organizations, a few commercial banks, and the ‘Paris Club’ of rich countries to something much more complicated. In recent decades, emerging markets and developing economies have borrowed proportionately more from international bond markets with their dispersed private investors, and tapped new non-Paris Club lenders like China.

From the sovereign’s perspective, this makes a potential debt restructuring operation particularly complicated. One of the biggest dilemmas facing Ghana as sovereign debtor embarking on a restructuring will be the extent to which the restructuring burden should be borne by holders of domestic-law versus foreign-law governed debt. There are several considerations at play. One issue refers to the means of restructuring: the Ghana can unilaterally change the terms of domestic law-governed debt by making appropriate changes in its domestic law. This gives the country enormous flexibility in designing the restructuring and limiting holdout behavior (see Case Study: Greece). Moreover, if domestic-law debt is denominated in local currency, the country may also choose to “inflate away” the debt problem by printing money.

Another set of considerations relates to the collateral effects of a debt restructuring. While restructuring local-law governed debt may be easier from a legal perspective, this debt may be disproportionately held by local institutions such as domestic banks. A restructuring of that debt may undermine the health of the banking system and worsen the prospects for restoring economic growth. Governments may also have political incentives to avoid or minimize the restructuring of domestically held debt. Those claims are often held by voters or political insiders. On the other hand, focusing a restructuring exclusively on domestic debt may help to reduce the reputational costs in the eyes of the international capital markets. Ghana with a strong desire to maintain access to external borrowing may therefore have an incentive to restructure domestic debt before contemplating a restructuring of debt held mainly by external creditors. One example is Russia’s 1997 default and subsequent restructuring which excluded foreign law bonds issued by the Russian Federation.

Restructuring foreign-law governed bonds will require other tools to limit holdout behavior ( “Carrots” and “Sticks” below) because the sovereign debt cannot unilaterally change the terms of the bonds by legislative fiat, as it can with domestic-law governed bonds. An attempt to place the major weight of the restructuring on creditors with foreign-law governed debt, however, may give rise to inter-creditor equity concerns. Foreigners may refuse to agree to restructuring terms that effectively subsidize full payments to creditors holding domestic-law governed debt. In the International Monetary Fund’s definition, debt sustainability incorporates the concepts of solvency and liquidity without making a sharp demarcation between them. From a liquidity perspective, the country must be able to refinance obligations falling due and to finance new fiscal deficits at interest rates that prevent market stress or aggravate the solvency position. From a solvency perspective, the country must be able to sustain a given debt level without a substantial risk of reverting to explosive debt dynamics or requiring protracted primary surpluses that could undermine growth.

The starting point of the discussion is a situation where Ghana is now experiencing unsustainable debt, and wishes to address it through a domestic debt restructuring. In this setting, the paper answers three questions. First, what may be relevant considerations for a debtor that needs to decide whether to restructure domestic debt, external debt, or both? Second, what practical, legal, and procedural issues need to be addressed in the context of a domestic debt restructuring? Third, how can the adverse spillovers of domestic debt restructurings on the domestic economy and the domestic financial system be mitigated? IMF report (2021) posited that when facing liquidity or solvency pressures countries will have to employ a range of strategies to reduce the real burden of domestic public debt.

The debt reduction strategies include financial repression, high inflation, retroactive use of withholding taxes, and overt debt restructurings by law or executive acts or through negotiations with creditors. Based on the type of public debt held by private creditors (foreign law debt, domestic law debt, or both) and the approach to reducing the real burden of domestic debt, the public debt reduction/restructuring episodes generally fall into one of five categories: (i) high inflation/financial repression episodes (ii) standalone external debt restructuring ; (iii) standalone domestic debt restructuring; (iv) external debt restructuring accompanied by high inflation or financial repression ; and (v) comprehensive restructurings with both external debt restructuring and domestic debt restructuring. The government can use financial repression can take many forms, including (i) directing state-owned banks and enterprises or government-controlled entities (e.g., social security fund) to hold government securities, (ii) running interest-free arrears with domestic suppliers for extended periods, and (iii) setting interest rate on government securities below market rates.

For the purpose of this article, Ghana’s domestic debt restructuring refers to changes to contractual payment terms of public domestic debt (including amortization, coupons, and any contingent or other payments) to the detriment of the creditors, either through legislative/executive acts or through agreement with creditors, or both.

Ghana is currently facing debt servicing difficulties has broadly speaking three options: debt reduction; debt rescheduling and debt reprofiling. In the Ghana’s domestic debt restructuring options:

- Rescheduling is a change of the maturity dates for amounts of principal or interest falling due under the affected debts and introduce grace periods,

* debt reduction that reducing the principal amount of the debt (in the jargon, a principal “haircut”), and

- Reprofiling is about reduction of the interest rate on the debt (in the case of bond indebtedness, a “coupon adjustment”).

Reprofiling can also connotes a transaction in which maturities are extended but there is no principal haircut and typically not even an adjustment to the coupon. Domestic-law debt restructurings proceed faster than foreign ones, often through extensions of maturities and amendments to the coupon structure. According to Asonuma and Trebesch (2016), an extension of maturities is by far the most frequent form of restructuring, featuring in almost 80% of the episodes. Amendments to the coupon structure are also fairly frequent, while face value reductions are rare.

7.0. Arguments for Restructuring Ghanaian Domestic Debts

Restructuring domestic debt is a tool that can be used by Ghana as it has been facing fiscal and economic stress. To be successful, domestic debt restructuring should be well designed to avoid doing more harm than good. To ensure that it is done right the first, the country’s domestic debt restructuring should be part of s broader policy package that effectively addresses the underlying problems and debt vulnerabilities. There has been much media and academia attention on what creditors will do in the case of Ghana’s debt restructuring. It seems there are there approaches: the foreign holders in the domestic bonds will prefer to have a haircut (debt forgiveness), whereas financial institutions seems to have been using rescheduling and re-profiling in recent years (as in the case of Angola and Ecuador).

The starting point of the analysis in this section is that Ghana has found itself at a point where its public debt is no longer sustainable and has to decide which obligations to restructure according to 2023 Budget statement to the Parliament of Ghana’. There have been suggestions that Ghana would prioritize the restructuring its domestic debt as the interest costs constituted about 75% of the country’s revenue while external debt service is only 25%. But this begs the question: what does a debt restructuring entail and where does the burden fall especially if haircuts – which can include a reduction in outstanding interest payments – are part of the policy mix? Ghana’s commercial banks held about 30% of the domestic debt and 50% of the total banking sector assets in 2021. Domestic debt restructurings often proceed much faster than external ones, but they can also protract significantly. It is understatement that Ghanaian domestic bondholders have suffered an additional implicit inflationary haircut as a result of higher inflation since the beginning of the 2022.

However, as accumulated domestic debt has grown over the past six years, interest payments have come to account for a greater portion of government revenue leading to debt restructuring programs to reduce near term payment obligations

Domestic debt restructuring cannot be ruled out, especially given the very high nominal cost of cedi-denominated government debt. Still, it is likely to involve some caution to avoid triggering a self-defeating ‘doom loop’ affecting the domestic banking sector’s solvency and stability The government’s domestic debts are so large relative to the size of the national economy that the Bank of Ghana is unable to tame very high inflation purely through monetary policy. While continuing the high cost of rolling over the government’s domestic debt would perpetuate the problem, the interconnectedness of fiscal solvency and inflation makes monetary policy less effective, even with high interest rates that have a negative impact on investment and growth.

The government restructuring the domestic debt will provide a foundation for resetting these negative dynamics and achieving conditions conducive to economic growth, with reduced interest rates and reduced inflation. Reducing domestic debt through explicit restructuring allows the costs to be targeted progressively to those sectors of the economy that are most equipped to bear the burden of debt reduction. Thus, any attempt to restructure the domestic debt without a compensating policy action could leave the banking sector highly vulnerable to further distress. Restructuring domestic debt focused solely on haircuts would severely affect asset quality and increase non-performing loans much higher than the current 15.7%but it may impact negatively on Tier One capital of the IFRS 9 is applied.

It would also reduce private sector lending, already under severe strain from 20-year high inflation. Pensions and other institutional investments are also likely to suffer significant losses which produce crisis of confidence in domestic debt market. These challenges have forced Ghana’s government to approach the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for an economic support package. Part of the engagement will involve a new assessment of the sustainability of the country’s debt. Debt sustainability analysis classifies countries into four bands: low risk, moderate risk, high risk, and in debt distress but recent classification by World Bank as high distress country has forced the government to seek IMF Bailout of US$ 3billion. This is based on certain thresholds for key public debt indicators. Ghana’s last analysis, conducted by the World Bank recently high distress country has changed the previous classification, as being at high risk of external debt distress and overall debt distress in 2021.

According to Ministry of Finance 2023 budget statement in November, 2022, Ghana has been classified as a high debt distressed country after debt sustainability analysis which requires that government to ensure that debt is brought to sustainable levels by reducing interest rates and by lengthening the maturity period of the domestic debt. In the modern period, we stress the two debt relief initiatives that were spearheaded by the United States: (i) the Baker plan of 1986, which granted debt relief by reducing interest rates and by lengthening the maturity of selected developing country debts and (ii) the Brady initiative of 1990, which set the stage for face value debt reduction. In 2010 Jamaican government adopted the debt exchange or debt swap designed to offer relief to fiscal accounts through a sizable reduction of the coupon rates as well as through the extension of maturities on most domestically issued bonds which the Government of Ghana could replicate.

The assessment was carried out jointly by the IMF and the World Bank. The recent comments by the Head of Africa Department of IMF Office in Washington DC added that there are conditionalities which may require a country to restructure its public debt if it reaches unsustainable levels. All noises coming through from both international capital market, credit rating agencies and Bretton Woods institutions point to public debt restructuring of some sort. The desirability of Ghana’s domestic debt restructuring would be beneficial to the government, if the government can act soon and restructuring is carried out early, so that economic policy goals could be achieved without needing to impose haircut on coupons or investments of domestic creditors. It would be adequate for the government to simply to reprofile its domestic debt: i.e. extending repayments further into the future to say to 2030.

Domestic debt restructuring should not be standstill, as the real value of the domestic debts has already considerably been eroded by higher inflation, the cost to government of rolling over maturing domestic debt remaining very high thus costing the country about 75% of the tax revenue. Government is currently paying around 33% to 34% annually for new short- government securities. The real value of domestic debt has already halved due to high inflation and Financial Repression (IFR), as the Cedi free floating to the US dollar (now called a ‘free floating’ exchange rate) collapsed from GHC 6.04 in December 2021 to GHC 13.899 on October, 2022 approximately 100% depreciation of the Cedi against the US dollar on foreign debt. There is an understandable concern about the implications of domestic debt restructuring for domestic banking system, the pension funds and the national economy (IMF, 2021). However, this article focuses on the benefits of domestic debt restructuring.

According to Verite Research Group (2022) restructuring domestic debt will (i) provide a quicker path to debt sustainability and economic recovery. It is likely that the best debt restructuring package that the country can obtain from its external creditors will still leave Ghana with severe problems of financial (in)solvency and debt sustainability. Assuming that Ghana manages to negotiate a haircut on (International Sovereign Bonds (Euro bond 5% and 10% haircut on multilateral/bilateral loans, the ratio of debt to GDP is still projected to decline to 68% by 2032. However, if the maturity of domestic treasury bonds were simultaneously extended by 10 years, the ratio of debt to GDP would rise to just 68% in the next 10 years after reaching nearly Debt to GDP 107% according to World Bank

(ii) The restructuring of the Ghanaian domestic debt will provide a foundation for recovering macro-stability. Government’s debts are so large relative to the size of the national economy with high domestic interest that the Bank of Ghana is unable to tame very high inflation purely through monetary policy. The continuing high cost of rolling over government’s domestic debt will perpetuate the problem. The interconnectedness of fiscal solvency and inflation makes monetary policy less effective, even with high interest rates that have a negative impact on investment and growth. Domestic debt restructuring will provide a foundation for resetting these negative dynamics and achieving conditions conducive to economic growth, with reduced interest rates and reduced inflation.

(iii) Domestic debt restructuring will achieve a more targeted and progressive sharing of the adjustment burden. The present path of quietly restructuring domestic debt through high inflation disproportionately hurts Ghana’s wage-dependent working population and increases poverty as well as destroying the welfare of Ghanaians. Reducing domestic debt through explicit restructuring allows the costs to be targeted progressively to those sectors of the economy that are most equipped to bear the burden of debt reduction.

(iv) Reduces the risk of repeating the present debt crisis in the medium term. It is not unusual for countries that enter into insolvency and debt restructuring to fall back repeatedly into the same set of problems. The main reasons are poor governance, political expediency, over-optimistic fiscal targets, and shallowness of the debt restructure. Currently Ghana faces high risks in all three areas. If interest rates remain at current levels and the government’s highly ambitious targets for increasing revenue are not fully met, the country faces the prospect of a relapse into another debt sustainability crisis in the medium-term. An early domestic debt restructure can mitigate that risk – even though it cannot compensate for the continuing risks of poor governance.

(v) the restructuring of the Ghanaian domestic debt is that local debt is expensive as interest cost of the domestic debt is about 75% of total debt servicing cost that shows that Ghana’s domestic debt market is not yet deep and liquid. Given that interest payment on the domestic debt accounts for 75% of total interest cost, it is not unsurprising that some participation from holders of local debt will be included in this debt restructuring plan. The small domestic debt market and a limited pool of funds means that restricts government to borrowing short-term and at higher interest rates.