Gifting the Saviour

So apparently, Jesus, on his birth day, dipped his little baby feet in gold.

Three Wise Men converged one evening… Hearing news of the birth of the Messiah, three great Wise Men converged one evening, each bearing gifts… History lists these gifts as gold, frankincense and myrrh. Onwards to the birth place of the Messiah these three went, led by a bright star, carrying these three gifts. God made flesh, Christ was to, on his birth day, receive three gifts, two of which had pronounced spiritual significance—frankincense and myrrh. And the other one, it reigned supreme on earth—gold. It was a symbol of wealth, authority, and earthly rule—befitting for a king, even an otherworldly one as Christ was. I, for one, like how the Bible begins this list of three with the mundane, the glorious mundane—gold.

Now, I have a theory… That gold that first Wise Man brought to Christ, it was dug up from Ghana. Hear me out. Where else could he have derived this finest of gold (as it was bound to be), if not from this country of ours? Being a gift intended to be brought before the Lord, this gold had to be at its finest. So the city of Bethlehem, lying in the nation of Palestine, a nation clinging on to the crown of Africa as though holding on to dear life… Bethlehem lying in Palestine, and Palestine, being remnants of the ancient supercontinent, Pangea, not altogether divorced from Africa, nationals of this country, setting out in search of the finest gold, were bound to come down south in search of the top gold producers closest to them, but not so south that they would land in South Africa, because half-way through the African continent, lying on the far west, was the country of Ghana, brimming with gold. So gold it was—from Ghana straight to the Messiah.

Admittedly, I may have made this whole story up; but we’re going to stick with it, and see where it takes us.

The Big Folks’ Club

“Africa is not the only resource-rich land—it is not the most resource-rich land. We are blessed, abundantly blessed, but not exclusively so.” We made this statement in last two weeks’ article, ‘Human Sacrifice’, a piece which attempted to nudge us out of our comfort zone—our ‘all praise to our natural resources, none to our human resource capital’ comfort zone.

But then you have the matter of gold. Let’s just go ahead and say this: when it comes to this resource, Ghana has for centuries earned its past name tag—Gold Coast. If not for its colonial tinge we may have just kept that name, because it’s a perfect description of the fact at hand. Worldwide, we are consistently placed in the top ten gold producers list. Presently we are sixth globally; and in Africa, we are first. Having kicked South Africa to the curb, this country of ours, having a landmass of 238,533 square kilometres, is currently Africa’s leading producer, and the world’s sixth largest producer of gold, producing approximately 132.5 tonnes [2019 production].

This is telling, isn’t it?—this matter of landmass weighed against natural-resource prowess. I mean, it is not for nothing that Russia is so resource-rich—with its vast land size, the chances of occurrences of natural resources, in all its varied forms, are very high. And in fact, it is the same for all these five countries beating out Ghana on the top gold producers list. They are all by far larger than us. China, the world’s leading gold producer, for one, has a land size of 9.6 million square kilometres; Russia, as already mentioned, the world’s second largest gold producer is also the largest nation by land size, spreading a whopping 17.1 million square kilometres; Australia, third on the gold list, is almost 7.7 million square kilometres big; Canada, the world’s fourth largest gold producer has a land size of 9,984,670 square kilometres; and USA, placing fifth on the gold ranking, has a landmass slightly smaller than Canada’s—9,833,520 square kilometres. And then you have Ghana, tiny Ghana, coming in with barely a quarter of these land sizes, yet sitting ever-so proudly on the gold list—the sixth largest gold producer in the world. This is no small feat. In fact, this might just be where our perception of our indomitability in natural resource endowment, across board, stems from.

The gold in the nation’s flag is not big-headedness. You and I—as I write, as you read—we might just be sitting on gold. At this mention of money, I can almost hear you hum Article 257(6) of the 1992 Constitution. “Every mineral in its natural state in, under or upon any land in Ghana, rivers, streams, water courses throughout Ghana, the exclusive economic zone and any area covered by the territorial sea or continental shelf is the property of the Republic of Ghana and shall be vested in the President on behalf of, and in trust for the people of Ghana.” [Emphasis yours.] This tune you just sang is repeated almost verbatim in section one of the Minerals and Mining Act, 2006 (Act 703).

So here you are, waiting to lay claim to what’s yours. And what’s yours extends far beyond gold, even though this article has, to the writer’s own dismay, led boldly and primarily with it. We have on our hands also, the diamonds, bauxite, manganese… Let’s end the list here and see what the law says regarding this matter of ownership.

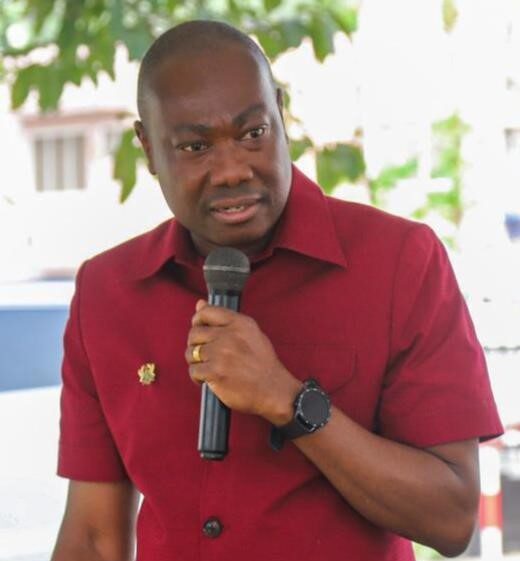

I would be remiss if I do not mention the fact that Mr. Martin Ayisi agrees with you wholeheartedly on this point. On this point of unapologetically laying the fullest, the most optimum of claims to our land and the natural resources that proceed therefrom, Mr. Ayisi, the CEO of the Minerals Commission, a fellow citizen, is very passionately on the same page with us all—I daresay—jealous, zealous citizens. “Over hundred years of mining activity in this country, mining has to fully and continuously benefit the Ghanaian. And that’s the job we, at the Minerals Commission, have set out to do.” Mr. Ayisi’s conviction is infectious.

Needs No Introduction

Mr. Martin Ayisi needs no introduction, but bringing you today’s piece with him, we are going to proceed with an introduction still. There is no way of keeping his vast exploits and expertise brief, but we are going to have to try. Mr. Ayisi is a lawyer—a mining and petroleum legal expert, having over 20 years of experience in the field. Before deservingly taking this position of CEO of the Minerals Commission, he served as Deputy CEO for almost three years. He’s served as a member of the board of directors of both GIISDEC (Ghana Integrated Iron and Steel Development Corporation) and GIADEC (Ghana Integrated Aluminium Development Corporation).

Mr. Ayisi has offered consultancy work for national, continental, and international institutions and agencies—agencies like the International Institute of Sustainable Development (IISD), and the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) (its Annual Workshops on natural resource contract negotiations); countries like Kenya (its Ministry of Mining), and the Kenya Extractive Industries Development Programme (KEIDP), etc. The wealth of knowledge Mr. Ayisi has garnered through this all, he has disseminated, serving as lecturer at the GIMPA Law School, teaching Environmental Law. At this juncture, I request permission to prematurely cut Mr. Ayisi’s very dense CV short, as we proceed to the matter at hand…

“When it comes to skills and expertise, we have the finest in the world—not just in Africa. We are a major exporter of skills globally. The nation remains a top priority destination for mining investors worldwide. Centuries of mining activity in this territory now called Ghana, these skill-sets have evolved with the times, the Ghanaian mining expert is not found only in low to middle-levels, we fill top-tier positions in this industry—worldwide. And that’s not the end of it. Ghanaians are no longer just employed expertise in this industry, but also owners in the sector. I mean, twenty years ago, starting off as a young lawyer right here at the Commission, I could not have fathomed that a time would come when Ghanaians would be engaged in the multibillion-dollar operation that is contract mining. But that’s exactly what we are witnessing now…,” Mr. Ayisi highlights.

This is all well and good, but even more so than Oliver Twist, Mr. Ayisi, together with the Ghanaian, wants more. Hence this new law, the Minerals and Mining (Local Content and Local Participation) Regulations, 2020 (L.I. 2431).

The Elements

Usually, over here, we tackle issues, first through a historical lens—it helps us appreciate and dissect the present more informedly. But this time around, we would have to adopt a kpa-kpa-kpa approach, and look first at the nation’s mining sector’s legal regime as we have it now, with particular emphasis on L.I. 2431. Because when it comes to money matters, time is of very dire essence. And I have a keen sense that with ‘gold’ on your mind, you don’t have the time nor patience to mull over history.

“L.I. 2431 is a law which sets out to quite bluntly put moneys in the pockets of Ghanaians. It is a law which sets out to lend credence to Article 257(6), and empower the Ghanaian with ownership of the very land on which they stand. It is indispensable then, that this law becomes an educational imperative for all Ghanaians. This is a task, the gravity of which the Minerals Commission fully appreciates, hence the nationwide educational campaigns we have carried out recently on the new Regulations.” Mr. Ayisi notes.

All laws, ever put out in human history, tend to have within them these elements:

- What the law sets out to do and who it sets out to do it for, or enforce itself against (Here, the law is ‘The Dreamer’)

- How it intends to do it (The law here is ‘The Action-oriented’)

- And there is this element of ‘woe betide you who disobeys’. (Over here, the law morphs into ‘The Enforcer’ – ‘The Punisher’ if you will, demanding stern accountability).

In L.I. 2431, the law, we daresay, is in its very elements. Let’s start off with ‘the dream’…

The Dreamer

The objects of the law are spelt out in regulation 1, and they can be categorised into these broad camps:

- the attainment of job creation for Ghanaians;

- skills and expertise development of the Ghanaian;

- boosting local industry/ownership;

- and the derivation of accountability to the stipulations of the law.

The Interpretation portion of the law uses the expression ‘Ghanaian content’ in lieu of ‘local content’, as though to say, ‘make no mistake, by local, we mean Ghanaian’, and defines the term as, “the quantum of value added to or created in the Ghanaian economy by a systematic development of capacity and capabilities through the deliberate utilisation of Ghanaian and material resources and services rendered in the mining industry value chain.” And this definition, one can’t help but note, captures the essence of the first three broad categories of objects spelt out above. Interspersed throughout the law are punitive provisions, waiting to take effect upon non-compliance—non-compliance without (legally excused) cause. And that’s that bit about accountability, as indicated under category four above.

On the matter of employment, sub-regulation (a) notes the purpose of the law as promoting job creation, businesses and financing in the mining industry value chain and the retention of these jobs in the country. Still related to this aim of job creation is the intent to see to the creation of Ghanaian mineral and mining-related support industries that will boost employment and consequently, spur economic development—this is stipulated under sub-regulation (d).

The law does not only seek to find the Ghanaian gainful employment, but also help them build and sustain something of their own. The Ghanaian is with this law, not only going to be the employee but the employer too, as provisions like regulation 1(e) sets out to “achieve and maintain a degree of participation for Ghanaians or companies incorporated in the country, in the [entire] mining industry value chain”. But not only is the Ghanaian to be a gainful owner of mining industry within this national border of ours, they are to also be empowered so as to “increase [their] capacity and international competitiveness” in the sector. This is indicated under regulation 1(c).

These are apt aspirations, one that can only be attained by the unwavering exhibition of sheer skill and expertise, innovation and adaptability, by our human resource capital. L.I. 2431 is cognisant of this fact, as it seeks to develop the capacities of Ghanaians in the mining industry value chain through education, skill transfer, expertise development, transfer of technology and technological know-how, and research and development. In this fast-paced Information Age we find ourselves in, knowledge is, more than ever before, mutable—quick to change.

With each rotation around the sun, this world of ours experiences an evolution. Knowledge, skills and expertise of today are tomorrow easily rendered obsolete. Consequently, it is nations that have mastered this art of change that drive the course of time in this highly industrialised, digital age of ours. L.I. 2431, again, is cognisant of the urgency of this fact. Ghana’s natural resources, its minerals—famously, its gold—will forever be subject to the pillaging reminiscent of the colonial era, should we not figure out a seamless and effective way of, with our own hands, driving the exploration of these resources, and steering national and global expertise and technological advancement in the sector.

The question of ‘to whom does the law applies?’ is answered in regulation 2, which indicates: applicants or holders of reconnaissance, prospecting, or mining licences, dealers or exporters of minerals, and mine support service providers.

The Action-Oriented

Now to the question of, ‘how does the law intend to do it?’… How does it intend to turn the words contained in its opening provisions, as discussed above, into action? The answer is a long one—contained in regulations 3 through to 14 of the law, where it is spelt out exhaustively, the local content requirements of the nation’s mining sector. We will dissect, individually, these provisions in subsequent articles. However, a quick run-through will do no harm. On the matter of skills transfer and the employment of the Ghanaian, the law provides its approach under provisions like regulation 3, where holders of reconnaissance or prospecting licences are required to submit to the Minerals Commission, for approval, a localisation programme for the recruitment and training of Ghanaians. The Interpretation portion of the law, regulation 20 defines a localisation programme as one that sets out to employ and train Ghanaian citizens, with the intention that they will eventually replace expatriates employed in a particular mining entity.

This right here is my favourite part of the law: “A person who does not comply with the localisation programme approved under these Regulations is liable to [among possible others] pay to the Commission an administrative penalty of one year’s gross salary of the expatriate involved, for each month or part of each month that the expatriate worked.” And this administrative penalty “shall be paid into an account established by the Commission for training of citizens for employment in the mining sector.” Here, the law adopts the ‘by hook or by crook’ approach to achieve its end of skills development and the employment of the Ghanaian.

We see a similar, albeit converse approach used in regulation 4, where applicants of mineral rights, or a licence to export or deal in minerals, or to provide mine support services, who intend to employ expatriates in their operations are to submit a proposal to the Commission for a grant of an immigration quota. The proposal shall indicate, among others, the position this expatriate is to fill in the organisation, the remunerations, allowances, and other benefits to be due them, the duration of the contract, and the plans the applicant intends to undertake to employ and train Ghanaians to replace this expatriate(s)—if in fact, expertise and the lack thereof was the reason why they could not find right here in Ghana, a person befitting of that position.

I like this part of the law, because of the picture it paints. It’s like hearing a person employed in a position you would very much like to have as yours has come down with a terminal illness. Wouldn’t you have no option but to, upon hearing this news, pass by the organisation every now and then, wait behind the gate, and every person that passes, ask them, “Is he dead yet?” One can’t help but notice that the law, the Minerals Commission, and one of its leading crusader, Mr. Ayisi, does something similar for the Ghanaian under regulation 4.

‘Robbing Peter to pay Paul’…and those who are uncomfortable stealing from Peter, would rather, ‘robbing Judas to pay Paul’—these two descriptions are uninformed and unpatriotic. Neither is a good description of what is going on with this barely two-year-old law, L.I. 2431. What we have on our hands is a group of people attempting to lay a valid claim to that which is by natural right, theirs.

Our Independence is Meaningless…

You know what, Madam Theodosia Okoh was not only a brilliant artist, but an excellent storyteller too. Because she captured very succinctly yet poignantly, a national narrative with her specific ordering of the colours in our national flag. It goes: red, and then there is the gold… Ghana’s independence as a nation, literally fought for with blood (the red), is easily rendered meaningless, should the ‘black stars’, i.e., the human resource capital contained within it fail at effectively and with their own hands, mining the ‘gold’ contained within their national borders—the gold signified by the yellow, itself a synecdoche for national wealth… Our toil at independence becomes futile should we fail at effectively utilising our naturally endowed resources (both our human and natural resources) to drive national growth. To be free, but not free at all, would become our national narrative. That is enough to send shivers through a nation’s spine, so much so that the Minerals and Mining (Local Content and Local Participation) Regulations, 2020 (L.I. 2431) had to necessarily happen.

Inherently, this all can tend to feel elementary, can’t they? For a people in the confinement of statehood to have the upper-most hand on whatever economic activity prevailing in their nation, that can sound pretty elementary, can’t it? But here we have on our hands, a national narrative necessitating the codification of this mundane national imperative into law. This is the card we have been dealt. Having not entirely come into the global race of nationhood and industrialisation early and strongly enough, this is the cross we are left to bear. It’s never too late for rectification, is it? Hence L.I. 2431.

I, for one, want so badly for the Regulations to attain the success, across board, across the wide and varied minerals and mining value chain it sets out to cover, because of how inescapably indomitable the mining sector has remained in our national economy after all this time—decades following independence, and centuries, preceding the Republic. But perhaps no one wants this more badly than Mr. Ayisi himself, with his signature down-to-earth, open-door leadership approach, bent on seeing the Ghanaian’s feet dipped in gold (and other minerals)—bent on seeing the Ghanaian as principal driver of a sector so consequential to theirs and the rest of the world’s economy as minerals are. Afterall, wasn’t it Mr. Ayisi who went on national television and publicly announced his private phone number, asking viewers to, “WhatsApp me with all your questions…”

Outro

Let’s continue this conversation next week, for, as you know, there is a whole lot more to uncover with this new legislative regime.

And on the matter of Jesus and the gift of Ghanaian gold, Mr. Ayisi and I are fully aware of the fact that when we finally gain admission to heaven, Jesus would have vacated His right seat by the Father and would be standing right at the gate waiting for us to, as they say, ‘remove our mouths’. Even there too, we shall still stand by our story.