It’s an undisputed fact that BWIs remain very influential in shaping the structure of the world’s development and financial order.

Like many, I authored an article – a very scathing one – criticising the Institutions as a surrogate of western imperialism only meant to defend or expand the reach of western capitalism in the face of a potential challenge from then Soviet Union, and to promote American interests in particular.

My reference case was specifically about the spikes they placed under the wheels of Kwame Nkrumah’s developmental efforts. Yes! BWIs were significantly influenced by the US’s geopolitical strength; nonetheless, their mandates, focus and programmes have evolved greatly over time.

It’s significant to note that the Fund and Bank missions started shifting as they developed a focus on income inequality and poverty for the first time under World Bank President Robert McNamara.

Hitherto, the Bank was a poster-child for the Washington Consensus; but it has since moved on to become what is now referred to as the ‘Knowledge Bank’ – whereby it tries to position itself as the repository of ‘development expertise’. Isn’t it ironic we continue to belong in spite of averred scepticism and reservations? The last time I checked, one of the inalienable rights accruing to any human being is freedom of association.

The Bank is currently framed in twin goals of eliminating extreme poverty by 2030 and boosting shared prosperity. They try to achieve this in principle by direct lending for developmental projects; direct budget support to governments (Development Policy Financing); financial support to the private sector, including financial intermediaries (FI); and via guarantees for large-scale development.

It would be perversely counterintuitive to have these laudable goals and deliberately prescribe recovery measures which make life so unbearable for the one hundred and ninety members who subscribe to their programmes. The fact is that we normally run to them when we are in dire straits and needed urgent ‘surgery’ to be able to keep our heads above water. In such circumstances, it is a sick person who ought to take a bitter pill.

Many indisciplined countries don’t want to be accountable, they therefore abhor what is referred to as macroeconomic surveillance. If not, I wonder what’s so wrong with engaging the IMF as this precarious economic turmoil has our back is against the wall – obtaining short to medium-term lending that focuses on economic adjustment in the structural and financial space, and more importantly sanitising social policies to improve public sector resource management with the ultimate aim of reducing poverty seems to make sense.

Undoubtedly, we can turn to our favour the Fund’s useful advice and help reduce our vulnerabilities.

Long-standing critiques of the Bank and IMF have involved the economic policy conditions they promote which often come with ‘attached’ or ‘recommendations’ as part of loans, projects, technical assistance or financial surveillance (often referred to as conditionalities.) And that these conditionalities tend to undermine the sovereignty of borrower nations, limiting their ability to make policy decisions and eroding their ownership of national development strategies. This has particularly been the case with the IMF as ‘a lender of last resort’ for governments experiencing balance of payment problems or liquidity crises – the latter currently being Ghana’s situation.

At the macroeconomic level, following on from the original Washington Consensus, the Bank and IMF continue to push a particular set of macroeconomic policy prescriptions across almost all their member-countries. Most typically, these are fiscal consolidation measures (or austerity), and include reducing the public wage bill, introducing or increasing/improving the taxes regime in particular; labour flexibilisation, rationalising (cutting) and privatising social services; and targetting social protections and subsidies while maintaining low levels of inflation, corporate taxation rates and trade tariffs.

While historically the BWIs enforced conditionalities primarily through SAPs, today the IMF requires a ‘letter of intent’ from governments requesting a loan. To be approved by the IMF for a loan, the letter requires prior actions, quantitative performance criteria and structural benchmarks – though the latter continues to contain structural macroeconomic policy reforms.

In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, the ‘pro-cyclical’ approach was criticised for leading to a decline in economic activity that led to lower consumption, lower public revenues, lower investment in vital public services and higher levels of inequality – which in turn also lower growth. Critics have also repeatedly pointed out this approach does not address the root causes of governments’ balance of payments distress.

There is absolutely no human endeavour that is fool-proof. It is therefore unusual that many remain sceptical and apprehensive at the mention of these twin organisations. Perhaps what’s more important is to keep pushing the frontiers for a level playing field and win-win outcomes for member-countries.

As we keep evolving by the day, it is heart-warming to note the current stated aims of the Fund as promoting international fiscal and monetary cooperation, securing international financial stability, facilitating international trade, and promoting high employment and sustainable economic growth. They do these by providing loan programmes to nations with balance of payments problems, as well as policy advice either through technical assistance or bilateral and multilateral macroeconomic surveillance.

There is no question that the IMF and World Bank continue to be among the most relevant and significant, powerful norm-setters, conveners, knowledge-holders and influencers on the international development and financial landscape. In addition to providing temporary financial assistance for distressed countries to help ease liquidity and balance of payments constraints, the IMF is also increasingly engaged on the issue of poverty reduction – particularly for low-income countries that find it difficult to attract capital at affordable rates.

The IMF and Bank pronouncements on domestic policies can lead to important, positive reactions by ‘the market’ (including potential lenders or investors); thereby potentially increasing our financing options. This is because their policy prescriptions are oftentimes described as ‘best practice’, supported by ‘robust’ theoretical and empirical work.

It is true that the Bank and Fund’s bias toward fiscal consolidation, the private sector and debt servicing may constrain government’s flagship programmes, restrict public policy space and the overall ability to finance infrastructure and social services.

These notwithstanding, the BWIs’ transition from the Washington Consensus – underpinned by their trust in the efficiency of markets and consequently a drastically reduced role for state actors – to its ‘more progressive’ post-Washington Consensus successor acknowledges market failures and re-inserts the relevant role of the state.

This in no doubt can be seen as a significant change in Bank and IMF thinking, and their principle of the state merely facilitating the creation of an enabling environment for the private sector to pursue its objectives.

There are so many misconceptions surrounding the BWIs. Unknown by many, IMF money is cheap with diverse products – some of which are even interest rate-free as long as member-states’ borrowing keeps within the limit of 187.5% of their quota, beyond which a paltry rate of 2% kicks in.

Products like Rapid Finance Instrument (RFI), Flexible Credit Line (FCL), Rapid Credit Facility (RCF), Precautionary and Liquidity Line (PLL) and Stand-By Arrangements (SBA) come with few or virtually no conditionalities.

There are even some facilities that are interest-free irrespective of amount involved. They usually come with a moratorium with not less than five years grace period. Of course, a member-state must have solid economic fundamentals and be able to meet eligibility criteria to enjoy these fully. All these juicy facilities can be contrasted with Ghana’s not too distant past 7-year US$1billion Eurobond that attracted a market interest rate of 7.75%.

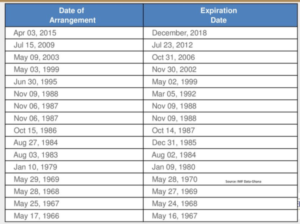

It would be interesting to play out the record for vindication of the country’s growth trajectory in all the sixteen times Ghana has been on the Fund’s programmes versus being on our own.

We have little to virtually no option than to bite the bullet and swallow the bitter pill soonest, rather than letting things degenerate before looking in the direction of the BWIs. For emphasis, the earliest the better; simply because the meat is down to the bone. Ghana’s economy is troublingly hobbled by widening current account and budget deficits, rampant inflation and a depreciating currency.

Interest rates also continue to pile up. At the root of Ghana’s woes has been out-of-control government spending, largely to pay salaries of an overgrown civil service, and over-reliance on foreign financing with overriding cost of debt servicing – all exposing the nation to swings in investor sentiments.

I do not therefore think the E-levy possesses the magic wand to get us out of this quagmire. I therefore think the IMF idea and the E-levy are not mutually exclusive. Indecision is as bad and a dangerous path to tread as getting good and bold initiatives wrong. It must also be said that the Fund, being a temporary stop-gap measure, won’t be a panacea for getting us out of the woods in the long run.

It would be highly irresponsible for us as a sovereign nation to neglect our responsibilities for development and blame the Fund for stepping in temporarily as a bastion of last resort when are backs are pinned to the wall. We have to take the bull by the horns and drink the kind of bitter drug meant for our perpetual cure.

Perhaps how Rwanda dealt with its development partners while in distress should be a classic case to guide us: Rwanda’s strategic use of international support was decisive in its success, more so than the amount it received. The more fundamental difference in Rwanda, relative to other fragile and distressed countries, was the extent to which self-determination increasingly played a role in how aid and other scarce resources was used; and the extent to which advice of development partners was taken.

The Rwandan government took to heart loan effectiveness principles of ownership in establishing structures for coherent coordination and mutual accountability – taking this to a benificial conclusion by implementing its own decisions, even when these were controversial or unpopular with its development partners.

Rwanda’s success story has become well-known in recent years, but the breadth, pace – and most importantly the ‘how’ – require special attention.

Beyond dining with the Fund, our best bet is to carefully direct Public investment to restructure the Ghanaian economy toward activities with higher returns to productivity and growth acceleration, while improving resilience to external shocks. Another major challenge beyond the Fund’s programme will be maintaining our discipline and significantly reducing tremendous wastage, leakages and thefts in the system without losing momentum on the growth of internal revenue generation.

The writer is member of Risk and Insurance Management Society and currently works for Provident Insurance Company as Risk and Compliance Manager.