By Peter Egyin-Mensah (COO & Founder of iJANU Limited)

Introduction: Setting the Stage for Ghana’s EV Transition

Over the past few years, Ghana has made significant strides in creating the groundwork for a clean mobility future. The Energy Commission’s forward-thinking policies and the efforts of the Drive Electric Initiative (DEI) have been pivotal in bringing electric vehicles into the national conversation.

Through regulatory clarity, pilot infrastructure rollouts, and active stakeholder engagement, they’ve helped move EVs from concept to a legitimate part of Ghana’s transport outlook. As someone working within this evolving ecosystem—through iJANU and other collaborative efforts—I’ve seen firsthand the growing appetite for local solutions that reflect our energy realities.

It’s within this context that we look outward, to places like California, not to copy, but to learn. Their experience offers valuable lessons on what it takes to scale—and how Ghana might chart its own course, guided by ambition but grounded in what makes our journey unique.

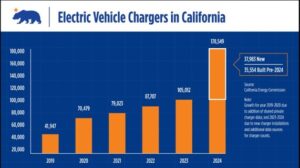

California recently achieved a landmark in electric vehicle (EV) infrastructure: the state now boasts 48% more EV charging stations than gas pumps. This didn’t happen by accident. It is the result of bold government leadership, meticulous planning, and substantial funding. Over the past few years, California doubled its publicly accessible charger network – growing from about 87,700 in 2022 to over 178,000 in

2024 – through aggressive investment and policy support. Governor Gavin Newsom’s administration dedicated billions of dollars to building out charging infrastructure, including a recent $1.4 billion plan to expand the nation’s most extensive EV charging network.

The strategy combined state funding, private sector collaboration, and data-driven planning to ensure chargers kept pace with the rapidly growing EV adoption. As a result, drivers in California today have “more options than ever to charge [their] vehicle,” with nearly half again as many chargers as traditional fuel nozzles statewide.

California’s Formula: Leadership, Planning, and Investment Pay Off

California’s achievement illustrates how a focused, comprehensive approach can accelerate the transition to clean transportation. The state government rapidly deployed funds into charging projects, from urban centers to hard-to-reach rural areas. Initiatives like the Fast Charge California Project – part of the CALeVIP incentive program – have awarded grants to install fast chargers at businesses and public locations across the state.

At the same time, agencies worked to streamline regulations and planning: California cut red tape by expediting permitting for new chargers, set reliability standards for charging stations, and developed a comprehensive infrastructure roadmap to meet its zero-emission vehicle (ZEV) goals.

Data mapping has been crucial; the California Energy Commission improved data collection to identify where chargers were needed most, helping add tens of thousands of previously uncounted chargers to the network.

The state also offered consumer incentives (including rebates and support for low-income EV buyers) to spur demand, ensuring that infrastructure growth was matched by a growing EV population. This strong leadership and planning have created a virtuous cycle: today 1 in 4 new car buyers in California choose an electric car, confident that a robust charging infrastructure has their back.

Ghana’s EV Aspirations and a Reality Check

Ghana, despite economic and infrastructure challenges, is looking to chart its own path toward EV readiness. The government’s intentions are clear – Ghana’s Minister for Energy and Green Transition, John Abdulai Jinapor, recently announced an ambitious plan to convert many fuel stations into EV charging centers as part of a broader clean energy strategy.

Speaking at an energy forum, he argued that Ghana must prepare for an influx of electric cars in the next decade and begin retrofitting existing filling stations to support them. This proactive vision is commendable: it signals political will to embrace the inevitable shift toward electric mobility and reduce dependence on fossil fuels.

However, simply transplanting the gasoline-station model onto EV infrastructure may not yield the same success in Ghana’s context. The strategy of converting fuel stations needs a reality check against how EV charging actually works and the on-the-ground conditions in Ghana.

EV Charging ≠ Gasoline Fueling: Rethinking the Infrastructure Model

Electric vehicles do not “fuel up” in the same way gasoline cars do, and Ghana’s EV strategy will need to account for key spatial, behavioral, and technological differences. For one, charging an EV typically takes longer than pumping gas, which encourages drivers to charge when and where their cars are idle – at home overnight, at work during the day, or while shopping.

In fact, studies in mature EV markets show that about 80% of EV charging happens at home (and a significant share at workplaces), not at public charging stations. This means a viable EV ecosystem relies heavily on convenient home and destination charging infrastructure, rather than exclusively on dedicated “charging centers.”

Spatially, EV chargers can be distributed almost anywhere there is electricity: in parking garages, malls, offices, apartment complexes, hotels – not just at highway rest stops or corner gas stations. Tellingly, Ghana’s few existing public chargers already reflect this pattern: units have been installed at Accra Mall, a hotel, and an industrial area, with only one located at a traditional filling station. Behaviorally, EV drivers prefer the convenience of plugging in during natural stops, rather than making special trips to a station as one would for gasoline.

Charging habits are fundamentally different from fueling habits. A commuter might top-up an EV at the office parking lot or a homeowner might recharge in their garage each night – a scenario far different from queuing at a petrol station weekly. Technologically, while fast-charging is improving, it’s not yet as instantaneous as fuel pumping.

Minister Jinapor’s optimism that new technology could charge an EV in “five to 10 minutes” hints at breakthroughs on the horizon (indeed, battery swap or ultrafast chargers are being tested), but most EVs today still require on the order of 20–30 minutes to get an 80% charge on high-power stations. Drivers are unlikely to want to wait around at converted gas stations for that long unless they absolutely must.

Therefore, an EV infrastructure plan overly focused on retrofitting fuel stations may miss the bigger picture: the real advantage of EVs is that, with a smart approach, charging can happen seamlessly in the background of daily life, wherever vehicles naturally park. Ghana would benefit from a more holistic strategy that goes beyond the pump mindset – one that fosters charging at homes, workplaces, and popular destinations, integrated with the way people live and travel.

Homegrown Innovation: Ghanaian Solutions for EV Infrastructure

A solar-powered EV fast charger installed by iJANU in Accra – one of Ghana’s first public high-speed charging stations – exemplifies homegrown innovation driving the country’s EV infrastructure.

The good news is that Ghana doesn’t have to rely solely on imported solutions; local entrepreneurs are already rising to the challenge of EV infrastructure with creative, context-appropriate ideas. A prime example is iJANU, a Ghanaian startup I founded as a Ghanaian-American tech entrepreneur, deployed the country’s first publicly available DC fast-charging station in Accra. What makes iJANU’s approach special is its adaptation to Ghana’s realities: the company is building a renewably powered charging network with a big emphasis on solar power that can operate independently of the often unreliable and costly grid power.

By harnessing Ghana’s abundant sunlight, iJANU’s stations reduce operational costs and ensure a cleaner power source for EVs – a smart tweak that addresses local energy concerns. Moreover, iJANU isn’t just installing chargers and walking away; it’s also providing an affordable pathway to EV ownership through structured leases, maintenance, and support services for EVs, helping to cultivate an ecosystem where electric cars can be serviced and kept running smoothly.

These kinds of complete, locally tailored solutions are exactly what will help build lasting confidence in EVs across Ghana. Importantly, iJANU is not alone. Other local innovators are also paving the way for an EV-ready future. For instance, SolarTaxi Ghana is assembling affordable electric motorcycles, tricycles, and compact cars locally, and pairing them with solar charging stations. Such initiatives not only expand charging options but also create jobs and technical expertise in the clean transport sector.

Even some forward-looking fuel companies and retail centers in Ghana have begun experimenting with charger installations (e.g. a Total station in Accra added an EV charger, and supermarkets like A&C Mall host charging points. These early efforts, though modest in scale, demonstrate that Ghanaian talent and businesses are capable of spearheading the EV transition if given the opportunity. As someone working on the front lines of Ghana’s clean mobility sector, I’ve seen firsthand the transformative potential of homegrown innovation—when it’s supported with the right partnerships and policies. The task for Ghana’s leaders will be to support and scale these solutions, rather than allow the country to remain an end-user of imported technology.

Government as Enabler: Policies to Drive Ghana’s EV Transition

To truly kickstart an EV revolution, the government must play the role of enabler and catalyst, creating the conditions for infrastructure to spread. California’s playbook offers a useful template of proven policies that Ghana can adapt to its own circumstances. Key strategies include:

-

Targeted Incentives and Subsidies: Reduce the cost barriers for EV adoption and charger deployment. California poured public funds into incentives – for example, offering grants and rebates to low-income households to help them afford EVs and home chargers. Ghana could implement tax breaks, import duty reductions, or grant programs for companies installing charging stations and for consumers buying electric cars or motorcycles. Earmarking funds to subsidize solar-powered chargers (to address grid reliability issues) could also accelerate private investment in the charging network.

-

Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs): Enabling Local Capacity, Not Just Infrastructure

Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) should be more than just a tool to mobilize private capital for EV charging infrastructure — they must be a strategic pathway to build local capacity and strengthen Ghana’s clean energy ecosystem. While California’s success was powered in part by collaboration with private sector players and utilities, Ghana has the opportunity to go further by structuring PPPs to intentionally nurture a domestic EV and renewable energy industry. Rather than focusing solely on international providers, Ghana’s PPP model can prioritize partnerships with local innovators, enabling them to scale their operations and embed technical expertise, job creation, and long-term economic value within the country.

Already, local companies are proving their readiness to take on this role. A standout example is iJANU, a Ghanaian-owned EV and clean energy company that currently operates the country’s first public DC fast-charging station, powered by solar and integrated with battery storage. But iJANU’s ambitions go further: over the next three years, it plans to assemble all of its chargers and energy storage systems locally, laying the foundation for a homegrown manufacturing base that can serve both domestic and regional markets. This vision is not just about self-sufficiency — it’s about turning Ghana into a hub for innovation, production, and service in the fast-growing electric mobility space.

This model should be incentivized and scaled. Ghana’s PPP frameworks can be tailored to support firms like iJANU, Charge Express, Smart Transit, SolarTaxi, Wahu Mobility, and XCharge EV GH — all of whom are actively developing or operating clean transport solutions in the country. By pairing these local firms with public resources or international partners under transparent, performance-based contracts, Ghana can unlock shared infrastructure growth and deepen technology transfer, skills development, and local assembly capabilities. For example, the government can offer land, tax incentives, and concessional financing to consortia that include Ghanaian firms and commit to sourcing or assembling equipment locally.

In this way, PPPs become a lever for industrial development, not just service delivery. Rather than importing charging infrastructure and outsourcing expertise, Ghana can cultivate an ecosystem where Ghanaians design, build, deploy, and maintain the critical components of its clean energy transition. This approach ensures that public spending and private investment generate lasting returns — in the form of skilled jobs, technical capacity, and export-ready solutions made in Ghana.

-

Infrastructure Mapping and Planning: Deploy chargers strategically by using data to guide decisions. In California, agencies gather detailed data on driving patterns and charger usage to identify where new stations are most needed, and they prioritize “shovel-ready” projects in underserved areas. Ghana should conduct a thorough mapping of its road networks, urban hubs, and highway corridors to plan an optimal charging network. This means pinpointing locations like city centers, busy transport routes, parking facilities, and even smaller towns that would benefit from a charger for inter-city travel. A clear national charging infrastructure master plan can help coordinate efforts and avoid a haphazard rollout.

-

EV Charging Corridors: Ensure drivers can travel long distances by establishing charging stations along major routes. California, for instance, has designated dozens of highway corridors for EV chargers under its federal NEVI program, so that an EV driver can traverse the state without range anxiety. Ghana could start by focusing on key travel corridors – such as the Accra-Kumasi highway, Accra-Cape Coast, and other vital links – and set up fast-charging stations at regular intervals. Creating these “charging corridors” in partnership with roadside businesses will signal to consumers that EVs are not just city toys but can confidently drive anywhere in the country.

-

Streamlined Permitting and Standards: Make it easy to build and use charging stations. California passed laws to expedite permitting for EV chargers (preventing local red tape from stalling installations) and is even developing charger reliability standards to ensure stations are functional when drivers arrive.