Recent Posts

Most Popular

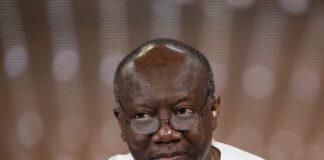

Ken Ofori-Atta is the major reason for current economic stability – Dr. George Domfe

Development Economist and a Senior Research Fellow at the Centre for Social Policy Studies (CSPS) at the College of Humanities, University of Ghana, Dr....

Emirates, Air China ink MoU to explore enhanced partnership

Emirates and Air China have signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) to establish a strategic framework for expanding their existing reciprocal interline cooperation.

The signing...

Frequent electricity systems maintenance is a red flag—not routine

By Elikplim Kwabla APETORGBOR (PhD)

Ghana’s electricity sector is flashing red and we must not ignore the alarm.

The recent surge in scheduled and emergency maintenance...

Time with the Amazons: UBA Ghana’s Women unite for inspiration and wellness

The women’s wing of UBA Ghana, U-Lioness, hosted an inspiring and engaging event dubbed “Time with the Amazons.” This session brought together women from...

Transport Minister tours GACL

In a move to advance Ghana's position as a preferred aviation hub in West Africa, the Minister for Transport, Joseph Bukari Nikpe, visited Ghana...