In the 14th century, some Portuguese seafaring entrepreneurs had a problem. They had discovered a lucrative business, supplying skilled workers to sugar plantations in Portugal and there was a demand for these workers.

The Portuguese entrepreneurs would dock their boats along the coast of West Africa, hide in the weeds and wait for unsuspecting Africans to come to the water to bathe or perform ablution for evening Muslim prayers, and then attack them, subdue them and take them back to their boats as prisoners to be eventually shipped to the sugar plantations of Europe. These Africans would fetch a decent price from the European farmers who had a need for such labor.

Unfortunately, the demand for such labor was higher than the entrepreneurs could supply. There was also a higher demand (and therefore profits) for young men than for women, because the young men had a higher chance of surviving the harrowing sea journey with little rations to Europe than the women and would have more years of productivity left in them when they arrived.

Children were also less desirable because they required special care to get them to an age where they would become truly productive. The challenge was that capturing these young men was an arduous and dangerous task because they would fight back fiercely. After thinking hard about how to solve this problem, the Portuguese seafaring entrepreneurs came up with an ingenious solution.

They decided to befriend the chief of the coastal village, and present him with desirable objects like matches, trinkets and mirrors. The chief then agreed to help the Portuguese capture other inland African tribesmen (from a different tribe) that were just as desirable to the Portuguese entrepreneurs who were simply delighted with the newfound exchange. This discovery was not what started the transatlantic slave trade; it was what brought it to scale.

Through this “cooperation,” thousands of slaves were captured and extradited to Europe where their resources were utilized to the benefit of Europeans at a fraction of the cost of what such labor would have cost if it had come from Europe; this was done with the complicity and cooperation of a small group of Africans who willingly sold out their African brothers and sisters for trinkets, matches and mirrors.

Why did the Portuguese decline to engage the Africans on a fair trade basis and recruit them with a fair offer of payment with salaries and benefits for working on European plantations? I believe there are two reasons. The first is economic and the second is psychological. The economic reason is that if the Portuguese farmers in Europe had to pay a fair wage to these African workers then they would either have made a loss on their farms or they would have made significantly less profit on their farms.

The psychological reason was that the Portuguese (who were eventually followed by the French and/or the British) believed that the Africans were not intelligent enough or civilized enough to be worthy of recognition as human beings with the same rights as Europeans, and therefore it was acceptable for their resources (the labor and energy) to be plundered without regard for anything but the minimum compensation required to keep the Africans alive.

Why did the coastal chiefs agree to sell out their fellow Africans for trinkets and mirrors to the pale strangers that they saw before them? Why did they not reject such deals as inhuman and offensive? I believe there are three reasons for it. The first reason is selfish, the second is self-preservational, and the third is short-sightedness. The first reason why they accepted the deals was due to a desire for personal gratification in the form of acquisition of something that others would not have (trinkets and mirrors). It was a selfish act to desire to have something that others would not have so that they could revel in their exclusivity.

For the second reason, the chiefs were also thinking that if these pale strangers had already been taking some of their tribesmen and women by force, this was a way to preserve the chief’s tribe so that the scourge of not being able to bathe safely by the water would go away.

The third reason was short-sightedness in the form of a lack of long-term planning by the chiefs who assumed that the pale warriors would be satisfied with simply collecting the resources from other tribes and that their alliance with the pale warriors would last forever. As history shows us, the pale warriors eventually reneged on their deals with the coastal chiefs and enslaved them as soon as they had secured their base in the African frontier lands with the help of the coastal tribes.

Fundamentally, the slave trade was the process of the acquisition of a large group of Africans’ resources at significantly below market/rock-bottom prices by non-Africans facilitated by a small group of Africans.

When the slave trade is broken down to this basic definition, it may be apparent to Africans who are living in the 21st century that the slave trade is still alive and well in Africa.

In this century, non-Africans are still acquiring the resources belonging to a large group of Africans for significantly below market prices and these acquisitions are being facilitated by a small group of Africans, who are selling out their brothers and sisters for the same reasons that the coastal chiefs did it centuries ago.

From 2000 to 2016, the Zambian government accumulated about US$6.37 billion in Chinese loans, with reportedly favorable terms for transport, power and government projects, in exchange for mining concessions with Chinese state-owned companies. Due to the opaqueness of the deals struck, there has been criticism about the unknown terms of the loan deals. In the neighboring DR Congo, in 2010, a US$6 billion resources-for-infrastructure agreement was struck with China, in which Congo promised Chinese state firms millions of tonnes of copper and cobalt in return for infrastructure projects.

Once again, the details of the deal were not made available to the Congolese citizens who are the rightful owners of the assets that have been traded in the deal. China is not the only non-African country that has utilized these secretive methods of acquiring African assets.

In Niger, French uranium-mining company Areva signed a deal in 2001 with the government of Niger that was kept secret from the citizens of Niger until human rights activists petitioned to acquire details of the deal and it was since revealed that Areva is benefitting from a sweetheart deal that allows it to pay 12percent less in taxes to the government of Niger compared to what it would have had to pay if it had been mining in a Western country. While the uranium has been profitably mined to the tune of an annual average turnover of US$4 billion by Areva and it powers energy production in France, the people of Niger wallow in poverty and power cuts.

In Nigeria, the campaign group Global Witness calculated in 2011 that the OPL 245 deal (an oil deal signed by the Nigerian government with oil giants Eni and Shell) was so unfair to the people of Nigeria that it deprived Nigeria of double its annual education and healthcare budget.

None of these acquisitions of assets at below-market prices could have happened without the facilitation of a small group of Africans who, due to selfish, self-preservation, and short-sighted reasons, are willing to sell out their brothers and sisters.

Dear African leader: take a page from President Paul Kagame, who learned that when we sell out our African brothers and sisters, the outcomes are devastating in the long run. In addition to ensuring that he does not sell out his fellow Africans, he has made it clear to Rwandans that betraying each other comes at a steep price. To quote Kagame, “You cannot betray Rwanda and not get punished for it. Even those who are still alive will reap the consequences. It’s a matter of time.”

Whether you are a public sector or a private sector leader, you may, from time to time, be presented with an opportunity to betray your continent by a non-African. This happened to me over a decade ago, when two non-Africans approached me and asked me to facilitate the recruitment of Sierra Leoneans for work in Iraq in return for a lucrative fee. Sierra Leone has a high unemployment rate, so the prospect of getting work in Iraq is certainly not a bad thing at face value. However, rather than simply saying yes, I asked them a few questions:

- What kind of work will they be doing?

- What kind of contract/terms of employment will they have?

- How is this being financed?

- How much is the principal employer paying your firm for the labor and how much of that amount are you passing on to the employee?

- What safeguards do you have in place for the Sierra Leonean workers in the event that they are unhappy with the employment/conditions in Iraq?

I asked these questions because I was not willing to sell my African brothers and sisters into employment conditions that would be opaque and unfair just so that I could make some money. I never informed the two non-Africans that I was not interested in helping them. However, after I had asked these questions which they promised to come back to me with answers, they never returned.

Dear African leader, please remember this: the slave trade would NEVER have reached SCALE without the complicity and facilitation of Africans. Today, Africa’s poverty and economic enslavement has reached SCALE because we, the Africans, continue to betray our fellow Africans. May the words of Paul Kagame be a sober reminder for all Africans.

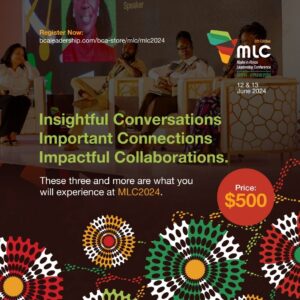

>>>The writer is a scholar and practitioner of organizational development and leadership and a leadership Coach and Facilitator. Over the past three decades, he has successfully coached and trained leaders in Africa, North America, and Europe. His passion for leadership enhancement was born out of his experiences as a cadet in the U.S. Military Academy (West Point) and as a military officer serving in combat in the Sierra Leone Civil War where he was shot twice. As the only Sierra Leonean with a Ph.D. in Leadership, Modupe was the founding Dean of the African Leadership University School of Business, an institution providing a Pan-African MBA degree to Africa’s mid-career professionals. He is the Co-founder and CEO of BCA Leadership (www.bcaleadership.com), an organization that has impacted over 4000 African leaders with coaching and knowledge-sharing services. He leads a team of forty-two Coaches across Africa and he is the curator of The Made in Africa Leadership Conference. Contact Modupe through email at [email protected]