The frequency of military coups in Africa is a fact that no longer shocks the international community. Since 1946, the continent has weathered an astonishing 224 coup attempts. To bring the stark numbers into sharper focus, 45 of Africa’s 54 countries have faced at least one coup attempt, and the average African state has contended with four since gaining independence.

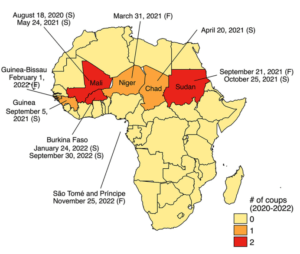

The statistics are sobering, even more so considering the recent surge. Eleven coup attempts occurred in just over two years, from August 2020 to November 2022. As numbers cascade down our news feeds, we begin to notice that Francophone African nations are particularly vulnerable.

Whether it’s Mali with coups in August 2020 and May 2021, Chad in April 2021, Guinea in September 2022, or the recent ones in Niger and Gabon, the French-speaking nations are at the epicentre of the continent’s upheavals, begging us to ask: what is going on?

Source: Colpus dataset, updated by Chin and Kirkpatrick (2023) through December 2022.

S in parentheses denotes a successful coup, and F denotes a failed coup attempt.

The “French pattern” can hardly be ignored. It is not just the frequency, but also the intensity of anti-France sentiments in these countries that turns heads. Why do the streets of Bamako, N’Djamena and Conakry resound with anti-French slogans when chaos strikes? Is there something more profound in this “Gallic connection” that sets the stage for political drama? Indeed, this is not a question with an easy answer, but it’s certainly one worth delving into. A glimpse into history, which constitute PART 1 of this article, may provide some clarity.

With recent developments like Niger reconsidering its relationship with France, and the latest BRICS summit discussing the possibility of expanding its membership, it’s evident that the geopolitical landscape is changing. In light of these shifts, the question that looms large is: what will the future of the Africa-BRICS relationship look like?

“In a world where ‘change is the only constant’, the shifting dynamics between Francophone African nations and France, as well as the BRICS’ vision for expansion, set the stage for an unpredictable yet fascinating geopolitical dance.”

The French connection: History and the quest for true independence

When we delve into the multi-faceted relationship between France and Africa, we find a story that spans more than five centuries. One might say it’s a tale of exploitation, but others see it as a complex yet vital partnership. History shows that France, as the third-largest slave trading power, transported an estimated 1.3 million Africans to the Americas. Tragically, around 200,000 individuals perished during the transatlantic journey. France needed coastal footholds to facilitate this trade and established one such port in Saint-Louis, Senegal, in 1659. For centuries, the interests remained confined to Africa’s coastal regions. However, the 19th century marked a departure from the status quo, as European powers began to engage in what has come to be popularly known as the ‘Scramble for Africa’.

The scramble and colonisation

Two critical motivators drove this shift: intra-European competition and the search for resources to fuel burgeoning industrial economies. Africa became an irresistible target, particularly regions rich in gold, oil and other resources. General Louis Faidherbe was appointed the governor of Senegal in 1854. Under his administration, France expanded its influence to include Gambia, though a cost-conscious French Government curtailed his ambitions to conquer the Niger Delta and Mali. However, the hiatus was temporary. By the 1880s, European powers abandoned shadow games in favour of overt territorial grabs, leading to the Berlin Conference in 1885, where the Berlin Act was signed. This act partitioned Africa among European nations, sidelining African rulers, sultans and tribal chiefs who had hitherto governed nearly 80 percent of the continent. By 1900, that statistic was reversed: almost 90 percent of Africa was under European rule.

The dark chapters and subjugation: Zooming in on Niger’s coup

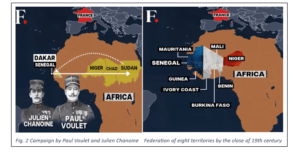

From history books to several news anchor desks, it has been documented that French colonisation was particularly brutal. In Niger, for instance, French officers like Captain Paul Voulet and Julien Chanoine led expeditions characterised by unfathomable cruelty. These military campaigns featured the decimation of entire villages and horrifying acts of violence, earning names like ‘The Killer Trail’ and ‘The African Apocalypse’. The brutality was so egregious that even the French Government sought to arrest the officers in charge, although their own troops ultimately killed them. By the close of the 19th century, France had succeeded in creating a federation of eight territories—Mauritania, Senegal, Mali, Guinea, Ivory Coast, Burkina Faso, Benin, and Niger—known collectively as French West Africa (see figure 2). Paris maintained its grip through a reign of terror, as evidenced by its ruthless suppression of revolts like the Tuareg rebellion of 1916 in Niger. Though African colonies contributed significantly to both World Wars, their inhabitants remained French subjects, not citizens, until post-World War II reforms in 1946.

Fig. 2 Campaign by Paul Voulet and Julien Chanoine Federation of eight territories by the close of 19th century

After independence: France never left

The transition from a colonial territory to an independent nation was far from a clean break in French colonies. It was more of a recalibration of power dynamics, with France still playing a pivotal role. In the case of Niger, the footprint of French influence remained deeply embedded in the country’s political, economic and social fabric after independence.

When France adopted a new constitution in the late 1950s, it presented its colonies with a referendum—a choice that Niger had to grapple with under the Progressive Party of Niger (PPN) leadership. This party was led by two dominant cousins: the radical Djibo Bakary and the moderate Hamani Diori. Diori, who advocated for greater autonomy within the French community rather than complete independence, won the debate. Niger voted to favour the new French constitution, and Diori eventually became the country’s president.

However, independence in 1960 and the subsequent presidency of Diori did not lead to the exit of France from Niger’s affairs. France utilised a strategy best encapsulated by the term “Françafrique”, a policy developed by former French President Charles de Gaulle to maintain a sphere of influence in Africa post-independence.

Through Françafrique, France nurtured personal relationships with African leaders, provided military support, and engaged in economic ventures. More than 1,000 French companies operate in these former colonies, making France one of the largest foreign investors in the region. This enduring influence extends to military matters as well. As of my last update in 2021, France had about 3,000 troops deployed across Africa, half of which were stationed in Niger. The purported objective was combating terrorism, but this ongoing military presence was often viewed as an affront to the sovereignty of Niger and other African states.

Perhaps one of the most palpable aspects of this lingering influence is the CFA franc, the currency used by 14 African countries, including Niger. This currency system requires that these countries deposit a significant portion of their foreign exchange reserves in the French treasury, thereby maintaining a form of economic dependence that many criticise as ‘monetary servitude’. Since the 1980s, French presidents have promised to diminish the extent of Françafrique.

Despite these pledges, the post-colonial relationship between France and Niger remains complex and fraught, leaving many questioning whether France ever truly ‘left’ its former colonies. The continued influence is a testament to the enduring legacies of colonialism, which do not disappear with the lowering of a flag or the signing of an independence declaration, but continue to shape geopolitical realities in subtle and overt ways.

Why the anti-France sentiments?

Do you know why most people in Niger and other former colonies dislike France and jubilate during coup? Several documented narratives signal that the French didn’t just come, colonise and leave; they stayed, continued to meddle, and extended their influence in ways that are palpably felt in these countries to this day.

This dual legacy (colonial and post-colonial) amplifies the sense of grievance. It’s not just the haunting memories and the traumas that fuel these sentiments, it’s also the flagrant and continuous meddling (military presence) under the guise of combating terrorism, making the resentment run so deep. Imagine being in a relationship where your partner claims to have given you independence but still controls your finances and occasionally drops by unannounced to tell you how to run your household.

That’s how France has operated in Niger and other Francophone African states. The issue isn’t just that France colonised these regions; it’s that France has never genuinely left. And until that happens, this lingering resentment will continue to fester, shaping the relationship between France and its former colonies in ways that are far from healthy.

From shadows to sunrise

It may be uncomfortable to present a brutal past that casts a long shadow over France’s relationship with Francophone African nations. While the past is a narrative of subjugation, the future can be chapters of change and mutual benefit. Is France willing to genuinely review its foreign policies with former colonies? Will Francophone African countries find the strength to decouple from the complicated web of Françafrique? Will the involvement of emerging economies, such as the BRICS nations, shift the balance of power and provide African nations the leverage needed to negotiate more equitable relationships?

There are no easy answers. The soil of these nations may be soaked in a history of sweat and tears, but I believe that from that very soil springs the hope for a future that sings a different tune. This new dawn is a possibility to redefine, reconstruct and reclaim a legacy that serves not as a chain to the past but as a ladder to a brighter, more equitable future. And that is a future worth fighting for.

Author:

Dr. Isaac Ankrah

Senior Research Fellow, Africa-China Centre for Policy and Advisory.

Lecturer, Ghana Communication Technology University.