The pulse of a nation’s democratic health beats through the perceptions and opinions of its citizens. Much like a skilled physician diagnosing a patient’s condition through careful observation and empathetic listening, understanding citizen perceptions serves as a stethoscope to gauge the vitality of democratic societies. This article employs a visual storytelling approach, utilising ten insightful charts derived from Afrobarometer data to provide a comprehensive snapshot of current socio-political realities in Ghana. Each chart explores a distinct facet of public opinion, shedding light on governance quality, economic perspectives, citizen engagement, and democratic participation.

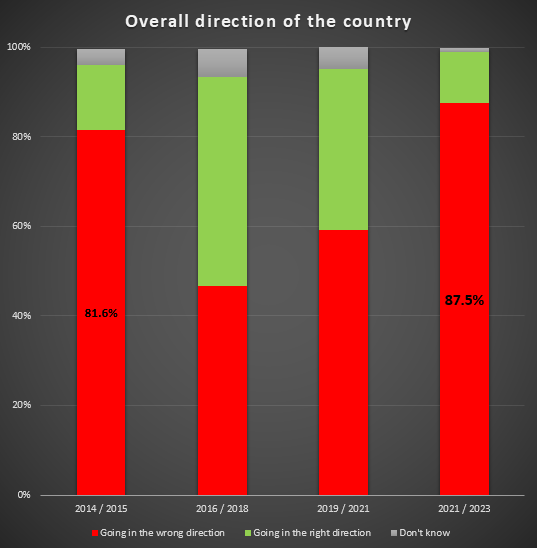

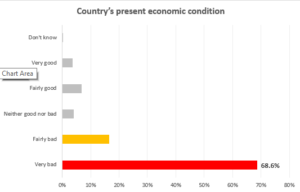

In the 2021/23 data survey, a striking 87.5% of respondents expressed concern that the country is moving in the wrong direction. While this discontent mirrors the economic downturn of 2014 when a substantial 81.6% believed Ghana was off course, many Ghanaians are now more pessimistic about the country’s direction. During the 2016/18 period, a relatively lower 46% held the same sentiment, reflecting the optimism around the change in power. These data points highlight the fluid nature of public perception, shaped by economic conditions and political dynamics. The recent numbers are a call to action for a change in tack for responsive governance and better policy measures that can steer the country toward a more optimistic path.

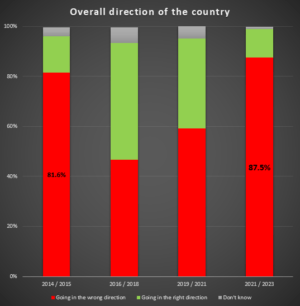

The latest Afrobarometer data reveals a substantial shift in trust levels towards Ghana’s key governance institutions between 2014/2015 and 2021/2023. Notably, those who trust “a lot’ in opposition parties witnessed a significant decline from 22% to 7%, reflecting diminished confidence in alternative political options. Similarly, trust in Parliament decreased from 16% to 8%, highlighting waning faith in legislative effectiveness. Even more jarring is the trust in the President, which also experienced a notable drop, declining from 22% to 14%. Concurrently, the proportion of individuals who expressed no trust at all in the President surged from 35% to 43%, indicating heightened scepticism towards executive leadership.

Furthermore, the erosion of trust extends to the courts of law, with a decline from 22% to 10%, potentially reflecting perceptions of compromised judicial integrity. Religious leaders, once trusted by 38% of respondents, also faced a decline in trust to 17%, underscoring changing perceptions of their influence and credibility.

These shifts collectively underline a complex interplay of factors influencing Ghanaians’ trust in critical institutions. The decline in trust across political, government, legal, and religious domains could indicate growing disillusionment, possibly influenced by political developments, economic challenges, or perceptions of institutional performance. As trust in fundamental pillars of governance and society falters, there is a clear call for renewed efforts to strengthen transparency, accountability, and effective communication between institutions and citizens, especially in a region experiencing a surge in non-democratic government takeovers. Addressing these trust deficits becomes imperative to bolstering public confidence, fostering a more robust democratic foundation, and enabling positive socio-political and economic outcomes for Ghana’s future. Because, as it stands, the dissatisfaction is unwaveringly evident. Ghanaians don’t trust their governance and leadership institutions as much as they did before.

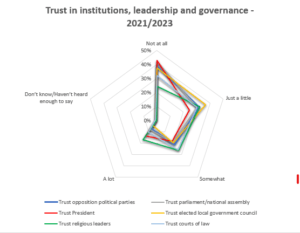

Herewith lies a rather sombre picture of Ghana’s socio-economic sentiment. A significant 68.6% of respondents deem the present economic conditions as very bad, reflecting widespread dissatisfaction. Similarly, a staggering 70% disapproval rate (disapprove and strongly disapprove) underscores discontent with the President’s performance. Furthermore, 53% express deep dissatisfaction with their living conditions, highlighting prevalent challenges. Notably, too, 69% perceive the country’s economic state as worse compared to a year prior, indicating a decline in economic well-being. A colourful tapestry of sentiments, collectively, these data points highlight the urgency for comprehensive measures to address economic concerns, enhance governance effectiveness, and improve citizens’ quality of life, fostering a more optimistic outlook for Ghana’s future. What we can do is not unknown, as shown in the chart 6.

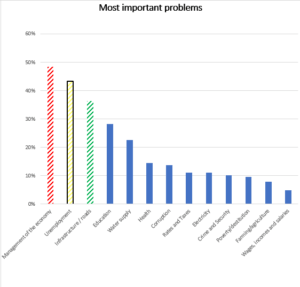

Understanding a nation’s most pressing issues is crucial for policymakers and citizens alike. As it stands, Ghanaian society is grappling with a range of social problems that require attention, including the management of the economy, unemployment and infrastructure/roads, in order of importance.

Knowing this is a golden opportunity for those concerned with doing work. By analysing public opinion through access to surveys like these, policymakers, captains of industry and civil society groups can gain valuable insights into the needs and aspirations of the people they serve or should be serving. In a world with limited resources and competing needs, this data-driven approach enables them to prioritise resources more efficiently and effectively and implement policies and programs that will, in actuality, address the most pressing issues facing Ghana today. That, not simply theorising, is a step closer to fostering a more inclusive society where everyone has an opportunity to thrive.

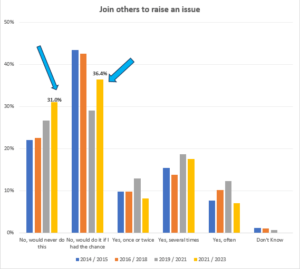

These figures illuminate challenges in democratic involvement, suggesting a significant portion of the Ghanaian population remains hesitant to participate in public affairs. However, the percentage of people who join others to raise an issue is back on the rise. This phenomenon may underscore the degree of civic disengagement and/or potential apprehensions about the impact of such actions – both cases worth exploring further. Enhancing democratic involvement requires addressing these factors and fostering an environment where citizens feel empowered and confident to raise their voices collectively.

Point 6: An unsurprisingly decent performance on empowerment and the shrinking of gender disparities, and the work cut out for all moving forward:

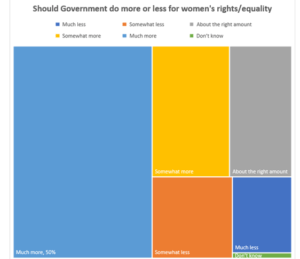

There is a dynamic societal discourse around Ghanaian perspectives on gender equality and women’s political leadership. A substantial 50% believe that the Government should be more active in advancing women’s rights and equality. Interestingly, a robust 62% strongly support the idea that women should have equal opportunities to hold political office, yet, some 15% strongly agree that men are superior political leaders and should be preferred over women.

It would make for great social discourse to look at the demographic breakdown for this 15%. Nevertheless, these viewpoints say two good things: a significant portion is for gender parity in politics, while a smaller minority clings to seemingly traditional notions of political leadership.

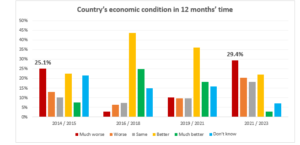

Ghana has seen economic hardship. Part of the giving the boot to the main opposition party in 2016 was based on a visible “fed-upness” with the management of the economy at the time. To see the percentage of people who view the country’s performance in the next year as worse than the peak of this dissatisfaction is shocking, worrisome and telling of a lot.

Conclusion:

These data points, among others, should colour every meeting of the Presidency, government and their relevant delivery units, and prompt an urgent response.

How has such dissatisfaction built so rapidly? Is there a broken telephone in the rapport between the leader and those being led? Indeed, the economic impact of COVID-19 and recent geopolitical occurrences have been severe. They, however, have only exacerbated longstanding national and sub-national governance and economic challenges in the country.

Perhaps finding better ways to communicate about the issues we face, the efforts needed and being made to address them, and the limitations that hamstring policymakers may play a significant role in building trust and addressing Ghana’s political and economic problems. It will, of course, help, too, if officials who contravene legislation and commit unlawful activities are held accountable.

So, while challenges exist, there is a palpable undercurrent of a desire for positive change: better government and governance, economic improvement, and gender equality. Addressing the trust deficits, fostering civic engagement, and ensuring economic gains reach further than a select few will be beneficial for Ghana as a whole. A glimpse at what is happening in the broader geographic region indicates people are no longer looking to sit on their laurels or be taken for a jolly ride. They want better, different.

Marie-Noelle writes in her capacity as a concerned Ghanaian youth. You can connect with her on Twitter at @marienoelleobj