It is a great privilege for me to have the opportunity to speak from this podium, which from my understanding has previously hosted many other distinguished speakers, and I am deeply grateful to the Vice Chancellor for asking me to follow in their footsteps. I intend to proceed as follows:

First, I will look at the global and domestic changing trends which have had profound impacts on economies of the world and our own domestic economy, and how leaders have responded. Second, I will look at the leadership mindset and profile required in Ghana to respond to these developments, and try and evaluate how our Ghanaian leaders have performed in the face of these leadership moments and tests. Finally, I will try and share some thoughts on the shifts in mindset and profile that our Ghanaian leadership will require if Ghana is to succeed in building a prosperous country on a sustainable and resilient basis.

As you can see from the topic – ‘Leadership for the future, Reflections from a 50-year Career in Corporate Africa’, this is not intended to be an academic thesis about Leadership; I am only here to share with you my Leadership experiences as a corporate executive.

Shocks to the world economy & the changing trends

In 2019, the world was thrust into a catastrophe from the COVID-19 pandemic – a medical crisis which morphed quickly into a major economic and social crisis across the globe. Many countries and companies buckled, others were able to adjust to demands of the new fractured world economic structures with supply chain disruptions, rising costs, rising inflation and depreciating currencies. Following on the pandemic’s heels was Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which worsened the disruptions, the uncertainties and economic and social dislocations which followed the outbreak of COVID-19. Together, the economic catastrophe caused by these two major developments are still gathering momentum with no end in sight.

But even before COVID-19 struck, the world was already going through a seismic technological transformation driven by rapid digitalisation of processes and systems, Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning, Big Data, Nanotechnology, Biotechnology, Robotics and Humanoid Robotics and many other technological innovations now termed the 4th Industrial Revolution. With these technological changes have emerged new generations; namely the generation millennials, the Gen-Z and now the AI generation – all young people born after 1989, whose expectations, skills and behaviour are completely different from what countries and businesses have been used to. Collectively, these developments are causing profound changes in the way the world’s economies and businesses are run, from global trade to global peace and security.

The danger is that many countries and businesses see the underlying drivers of these changes as isolated occurrences, but I share Alvin Toffler’s view that seeing them as isolated occurrences may blur our view of the underlying transformational trends. It is not surprising, therefore, that in Ghana the economic mess that we are in today is being explained away, simplistically, by government as having been caused solely by the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

While there is no doubt that the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have caused extreme disruptions to the global economies, it is also clear that the failure of Ghana’s leadership to understand the major global trends, which are dramatically changing the world, and their associated risks has been a major cause of Ghana’s economic crisis. And to this we must add Ghana’s own changing trends and governance weaknesses – which have long been ignored and which I now wish to address.

Changing trends in Ghana and Ghana’s leadership failures

When I first joined UAC of Ghana in 1966 as a management trainee, and until 1981, Ghana had six military regimes, several attempted or rumours of coup-d’états and two civilian administrations, namely the Busia and Liman administrations. On average, Ghana changed government every 22 and half months, with the only regime to stay in office long being that of Flt. Lt. J.J. Rawlings, which lasted 11 years from 1981 to 1992 – even if we discount the three months AFRC reign of terror from June 4, 1979 to 24th September 1979.

The 15-year period – also described as Ghana’s Lost Years – was characterised by chaos, economic and social uncertainties and dislocations, economic malaise, economic mismanagement, breakdown of governance and general economic deterioration. No regime, military or civilian, was able to put Ghana firmly on the path to sustained economic transformation to create a high income, prosperous economy that moves on its own axis.

Besides, governments during those 15 years were characterised by greed, graft and corruption, destruction of the country’s infrastructure from lack of investment and a complete failure of leadership to understand the changes that were taking place – especially the rapid globalisation of world trade which was propelling transformation of the Asian Tigers at that time.

Consequently, for 15 years Ghana never succeeded in building strong institutions and governance structures to drive sustainable economic transformation, growth and widespread prosperity. And not only that; Ghana also systematically destroyed the core governance values of transparency, accountability, integrity and reward systems based on performance and achievements.

The rise of the Asian Tigers from 1st World to 3rd World during the same period contrasts dramatically with what happened in Ghana.

Apart from South Korea, none of those countries was led by a military messiah or charismatic leader; each one of those Asian Tigers was led by a leader with a clear mission and a clear purpose, which they also executed with passion and commitment, as well as an uncompromising and unyielding adherence to good governance and respect for the rule of law.

Yet there seems to be a common refrain – especially recently – that Ghana needs a dictator, a strongman leader or a one-party state to develop. That cannot be true. J.J. Rawlings ruled Ghana for almost two decades: first as a military dictator and the proclaimed Ghana economic Messiah from 1979 to 1991, and continued for almost another decade from 1992 to 2000 as a civilian president; succeeding only in handing over a broken and bankrupt economy devastated by greed, graft and corruption to the Kufuor administration. It was no surprise therefore that Ghana had to be declared HIPC (Heavily Indebted and Poor Country) to secure debt-forgiveness after President Kufour took office.

But even with the massive debt relief under the HIPC programme, the Kufuor administration also succeeded in leaving a broken and bankrupt economy to Prof. Evans Atta Mills’ administration. After a successful IMF programme, the Mills administration made some impressive progress; but the succeeding administration also failed to build on the progress made by the immediate past-administration, while it was also accused of pervasive greed, graft, corruption and economic mismanagement, causing it to massively lose the 2016 elections.

The launch of the bold vision to create a ‘Ghana without Aid’ in April 2019 by the Akufo-Addo regime, championed by its finance minister Ken Ofori Atta, therefore appeared to break away from our sordid past. Unfortunately, that too has now become a mirage and mere slogan. Today, Ghana’s economy is once again in tatters – the economic crisis deeper than ever before, with perceptions of greed, graft and corruption more pervasive than in any other administration before it, and leaving Ghana still hugely dependent on Aid, Grants and Loans.

The reasons for Ghana’s continued woeful economic performance and the pervasive poverty after the overthrow of Dr. Kwame Nkrumah’s administration should therefore be sought elsewhere; it is definitely not due to the fact that we have not been led by a supreme dictator or a charismatic leader; the stark answer is that we have failed to identify, normalise, reward and promote the right kind of leadership and commit to good governance practices.

Why Ghana needs a new leadership mindset and profile

Permit me at this stage to summarise the reasons why Ghana needs new leadership for the future. I will then proceed to attempt establishing a new leadership mindset and profile required to build a new prosperous Ghana, borrowing from my experience from the private sector. I shall be brief because of time constraints.

The many years of political instability and the associated breakdown of good governance, loss of key democratic principles, disregard for the rule of law and destruction of our cultural values and behaviour which had shaped our governance arrangements even at our traditional levels, accompanied by pervasive greed and corruption, have succeeded in accumulating very destructive values and behaviour which have consistently undermined attempts to develop a prosperous country.

And we are also now very conversant with the fact that our world has changed considerably – driven by many disruptive technological changes, fundamentally changing the way we work, the way we communicate, the way we teach and learn, the way medicine is practiced, even the way wars are fought among many other changes to the lives of people all over the world.

Regrettably, Ghanaian political leaders after Dr. Kwame Nkrumah have failed to demonstrate any understanding of these complex external and domestic polycrisis, with their disruptive changes and impact on the country and its citizens. And the simple reason is that we have not had, and still do not have, leaders who can anticipate the future, adapt and respond by changing the governance architecture and operating model and execute appropriate resilient plans to shore-up the economy, grow it and create jobs and wealth.

Instead, they have always managed the past and the today. Yet leadership is not about the past, it is about today and the future; the past only provides leaders with lessons of mistakes which should not be repeated and the good things to build on. Ghanaian leaders post-Nkrumah have only focused on yesterday and today; that is why we are not going forward but rather going backward.

Identifying the new fit-for-future leadership profile for Ghana

So, what should Ghana’s future leadership mindset and profile be, how should we select the new fit-for-future leaders, and how can we identify, select, develop and sustain them? Ordinarily, these questions should not be difficult to answer. In my corporate days at Unilever and other companies, leadership development was a major enabler of business performance and taken seriously. It was deigned to:

- identify current and future needs of the business across the board

- define the right leadership profile that can respond to the needs

- identify potential candidates, (and take them through a selection process to select the most suitable candidates

- agree specific training and development plans as well as mentoring programmes, and

- share with candidates their career paths, together with annual evaluation schedules (usually based on potential, performance, values and behaviour).

It was a well-structured, transparent approach and had no room for nepotism, family and friends, favouritism, tribal relationships etc. – all the things that have undermined the development of quality human resources for the public sector in Ghana. Let me say up-front that I am very much aware that a business is not a country; however, I believe also that the principles of good Human Resource governance are the same for businesses and countries – even if the scope, the scale and the application may differ. And so, let me now attempt to apply my private sector experience to see how Ghana can respond to its current situation.

Ghana’s current and future needs

Given Ghana’s polycrisis situation, I have attempted to list below what I consider the most critical short-term needs which a new leadership is required to address.

Short-term needs:

- Leadership with purpose, not leadership by slogans

- Restoration of macro-economic and social stability

- Commitment to good governance

- Elimination of greed and corruption

- Promotion of honest and transparent partnership with the private sector

Medium- to long-term needs:

In the medium- to long-term, I see the following as Ghana’s most critical needs.

- Embed the Culture of Purposeful Leadership

- Sustain macro-economic stability over a minimum 10-year period

- Build a resilient economic model – build to last

- Invest in growth infrastructure

- Overhaul Ghana’s democratic framework and build an inclusive society

I will now comment briefly on each of the above needs.

Leadership with Purpose, Integrity and Conscience

One of the biggest causes of Ghana’s current crisis has been the dearth of quality leadership; leadership with purpose, integrity, honesty and conscience driven by bold plans; not rudderless leadership driven by greed and corruption – and we have had too many of the latter. Permit me to ask our leaders one simple question: has Ghana and Ghanaians been better-off because you have been our leader? A practical way to answer the question would be in terms of the legacy you are leaving behind.

Leadership must impact not only current but also future generations, including unborn generations – stakeholders who are never in the room when you take the decisions to shape the future of your country’s future, but on whom the decisions will impact most. In the private sector a poorly-performing CEO will be dismissed; but, sadly, that cannot be said of a political leader in a democracy. And that is the tragedy of our Ghanaian democracy.

Undoubtedly, leadership matters most in national development; a corrupt leader will bankrupt a country for personal gain; a rudderless leader will resist change and miss all the opportunities that come with change; an incompetent leader can only mismanage an economy to the detriment of creating wealth and jobs. I could go on and on, and it is for this reason that the issue of electing the right leaders has become key and urgent in Ghana. Also, what I see on the horizon does not give me confidence.

Restoration of macro-economic and social stability

Restoring macro-economic stability in Ghana is urgent and critical. The economy is traversing very difficult times. The deep deterioration of our fiscal and macro-environments – characterised by unsustainable debt with debt service ratio in excess of 100%; high levels of inflation, steep depreciation of the cedi; over 40-year record high interest rates; and elevated uncertainties and risks from debt defaults – has shattered the trust and confidence of investors in the economy. Reversing this situation is clearly urgent and requires a new leadership mindset.

And in Ghana’s case, what’s needed most is a dose of humility/honesty administered to Ghana’s leadership – so they admit that the country’s crisis was home-grown and not imported, and that it is also more complex than just the pandemic and Russia-Ukraine war. And let me be clear – going to the IMF will never be a permanent panacea to Ghana’s problems; otherwise we would not be where we are today, having been under Fund programmes 16 times already. What will bring a permanent solution is commitment to a clear purpose of building a prosperous country for all and an uncompromising commitment to good governance, which I now wish to address.

Commitment to good governance – a pre-condition for wealth-creation

The foundations of good governance have long been identified, extensively written about and discussed. These include probity and accountability, transparency, integrity, honesty, credibility, predictability and participation. I don’t intend to belabour these governance principles, but just to point out that they are at the core of good governance.

What I need to add and stress is that Ghana has consistently, and sometimes even deliberately, destroyed the institutions which were established – some by the Constitution, to enforce strict application of these governance principles. What I have seen in Ghana, and most of Africa, is rather a shift away from ensuring strong and functioning institutions to concentrating power in the hands of heads of state and leaders – who most often lack the capacity, integrity and willingness to pursue good governance practices.

Today in Ghana, power is over-concentrated in the presidency – and allegiance is often owed not to the state and its citizens but to the president and political parties. It is not surprising therefore that throughout our 66 years of political independence – during which because of greed, graft and corruption the country has repeatedly been plunged into dire straits – there has only been a cosmetic attempt to punish public officials for wrongdoing. We need to return to our traditional core values of integrity and good behaviour in public life, and we all know the adage ‘Dzin pa yε sen ahonya’, vis – ‘A good name is better than riches’.

Confront greed, graft and corruption

When I was Chairman of Stanchart, I arrived at the bank one day and saw a huge pull-up banner with the inscription ‘Corruption Kills’. In my office, I began to reflect on the banner, and it then dawned on me that the statement was pregnant with many truths.

Every cedi or dollar stolen from state coffers deprives a Ghanaian child somewhere of a life-saving vaccine, protective gear for medical practitioners – especially in this age of COVID-19 pandemic, food for SHS students, clean water and motorable roads for rural communities, safer highways and streetlights to prevent accidents on our roads and in our cities, hospital beds for pregnant women, investment in the economy to create jobs for the teeming jobless youths; and investment in science, technology, engineering and mathematics to build the foundation that would enable Ghana to compete in the 4th Revolution economy, etc. – things we should be taking for granted in this 21st century.

Indeed, it is because of corruption that we consistently have bad governments in Ghana and Africa. We are still poor and highly indebted after 66 years of political independence, largely because of corruption. Some ruthless actions are required to confront this destructive menace, without which we may become chronically distressed…permanently.

Build an honest and transparent partnership with the private sector

For many years, governments in Ghana have claimed to partner the private sector in pursuit of development. Yet all our governments have continued to promote and enlarge the public sector, while private sector growth and expansion has faced many obstacles. Given the tight fiscal space, it will only make sense if governments turn to the private sector for investment in certain types of projects capable of offering commercial returns: such as renewable energy, port expansion, major roads and highways, railways, tertiary medical and educational facilities, among many such opportunities.

The private sector has greater capacity to raise funds to invest in Ghana’s economy than what governments can do without further worsening the already-stressed debt burden. Clearly, relying on Foreign Direct Investment and a strong indigenous private sector working together is a better option for developing Ghana than raising debt for development.

Medium- to long-term needs:

Now, permit me to look briefly at what I see as Ghana’s medium- to long-term needs.

Embed the Culture of Purposeful Leadership

Mr. Chairman, from my corporate experience, let me be emphatic that leadership matters. It matters most in the delivery of any long-term strategic development plan; it is often at the core of success or failure. Leadership sets the tone for performance; it is responsible for the full application of all governance principles – integrity, accountability, transparency, credibility, humility and the rest. The leader sets an example of living the values, behaviours and culture of the organisation, and is accountable for delivery of the plan’s purpose and objectives.

It must be the same for countries, but sadly it’s not been so with Ghanaian leaders. Ghanaian leadership has regrettably been driven by short-term, political-cycle interests, and has demonstrated sheer contempt for good governance. They have been greedy and corrupt, especially in this fourth Republic, and we can see the impact through pervasive corruption, economic mismanagement, widespread poverty, unemployment and blatant disregard for the rule of law. Such leaders are clearly not fit for Ghana’s future.

Ghana requires from our future leaders a clear purpose to confront these endemic destructive habits and practices, which have undermined our efforts to build a transformed and prosperous economy. Thatcher and Tony Blair are good examples to follow: Margaret Thatcher doggedly and single-handedly confronted unions and the large and powerful state-owned corporations in the United Kingdom, which together had strangled the British economy and destroyed its capacity to grow for many years.

It was a fierce fight, the coal miners were on strike for 9 months – bringing the British economy to its knees. But she and her government held on; the unions were defeated and the British economy was saved. She had a clear purpose, and had planned its execution even before she came into the office.

Tony Blair, an avowed Labour leader, saw the merits of Thatcherism and decided to think and behave Labour but act Thatcherism. He succeeded in shifting the Labour Party away from being the big-government party interested in controls, to pursuing a market-economy that prioritised private investment. Blair continued with Thatcher’s privatisation programme to slim the size of government. That was the power of leadership with purpose. Building a country must be like building a house; one block on another, one at a time.

Sustain macro-economic stability – long-term

A stable medium- to long-term macro-economic environment is a pre-requisite for attracting long-term investment capital. Investment in manufacturing, agri-business, tourism, technology, research and innovation all require long-term capital; and therefore require medium- to long-term macro-economic stability, underpinned by stable political and social stability. But a stable macro-economic environment alone is not sufficient; it should be underpinned by an efficient and competitive micro-environment.

It is common knowledge that bad roads, poor social services, poor telecommunication-networks, poorly-educated manpower, among many others, pose even greater threats to Ghana’s attractiveness as a competitive investment destination.

In 1990 the Ghana government and World Bank issued a Report – ‘Ghana Toward a Dynamic Investment Response’, which identified the reasons why the private sector had not responded to all the reform initiatives Ghana had undertaken. The Report enumerated a long list of investment constraints in both the micro and macro-environments which frustrated investments. I am afraid all the constraints identified then, 23 of them, persist today. So, we should not be surprised that we have made no progress attracting strong private investment response – apart from those into the oil and gas and gold mining sectors, natural resources which cannot be replenished.

Ghana must not only ensure a long-term stable macroeconomic environment over a minimum of 10 years, but also invest aggressively in competitive economic and social infrastructure to modernise Ghana’s economy. That is the only way to build long-term confidence in the private sector and investors to attract long-term capital.

Build a resilient economic model

At the recently-ended Davos meeting of global political and corporate leaders, resilience was the subject that took centre-stage. Disruptions are not new, but the current era is increasingly defined by the interplay of complex disruptions with their disparate origins and long-term implications. They require economic models which are not only robust and sustainable but, even more importantly, resilient enough to withstand the many disruptive changes the world is currently going through.

Ghana has never been able to lay the foundations for a resilient economy; whenever commodity prices fall, the Ghanaian economy falls with them. The country has historically built no fiscal buffers, except during the Mahama administration when a conscious effort was made to create some buffers to shore-up the economy in the event of a crisis – only for all those funds to be dissipated within few years of this administration.

Every corporate executive knows that liquidity is key to survival. Sadly, the reverse is true of Ghana; as virtually all our governments have been profligate in spending far more than our means and repeatedly resorted to debt financing, which often goes to finance consumption. When the debts become unsustainable, we run to the IMF.

This cannot be a resilient development model going forward. But building a resilient economy should not be limited to creating fiscal buffers only. Ghana needs resilience in the supply of food and raw materials (Ghana is more dependent on imported food supplies than any other African country); in the supply of workforces skilled in modern science and technology; in the provision of social services; in maintaining a transparent legal and regulatory environment; and in ensuring a sound financial system, among many other critical areas.

Let me sound one cautionary note while on this subject of resilience. Ghanaian leaders must understand that the years of fossil-fuels are numbered, and there is so much discussion going on now throughout the world to stop their use. We cannot continue to depend on revenue from crude oil to build a resilient economy in the future, and we must act now. Ghana has the natural resources to produce hydrogen, and we must begin ‘thinking big’ to replace crude oil with hydrogen for export and local use to generate energy. Ghana needs leaders who can anticipate the future and ‘think big’.

Invest in growth infrastructure

We don’t need anybody to educate Ghanaian governments about the critical importance of investing in economic and social infrastructure as the foundation for economic transformation, development and growth. What I must emphasise is that there is an urgent need to pay attention to investment in Science, Technology and Innovation.

The 4th Industrial Revolution of this 21st century and the next requires that Ghana builds a workforce with skills and capabilities in Digitalisation, Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning, Robotics and many more. They are changing everything, and they are driving everything. We fail to invest in them at our own peril. And from my global experience, the best option is to pursue these investments in partnership with the private sector – like the MTN ICT Hub in partnership with the Ghana Digital Centre, which was commissioned in Accra yesterday.

Overhaul Ghana’s democratic framework and build an inclusive society

Ghana’s democracy is at risk, undermined by three very dangerous interlocking factors. These are:

- Inability of the electoral process to deliver the right political leaders

- Over-concentration of power in the Executive, and

- Costly but ineffective governance arrangements provided by the Constitution

I intend to focus only on the first one, for the sake of time because it is more relevant to our topic and poses the greatest danger to Ghana’s democracy. I have taken some time to read, with considerable trepidation, a recent publication by the Ghana Centre for Democratic Development on ‘Understanding How Dirty Money Funds Campaign Financing in Ghana: An Exploratory Study’. Indeed, dirty money now controls the selection and election of Ghana’s leaders from the Ward, Constituency and Regional levels to the national level. Only candidates described in the Report as “biggest spenders” get elected to become local executives, parliamentarians and presidential candidates.

The financing of political campaigns with dirty money and the monitisation of Ghana’s democratic process clearly undermine the possibility of Ghana ever getting the right leaders for the future; they put at risk any possibility for a purposeful transformation of our economy and the building of a robust, resilient and prosperous economy for future generations, while they also destroy any hope of a return to good governance in the public sector.

It is no wonder that our leaders become inward-looking, self-serving, greedy and overly corrupt when in office. It is a dangerous trend that must be confronted. Our democracy is no longer a “government of the people, by the people, for the people”. It is now government to serve the interest of wealthy individuals and special interest groups and corporates – and of course aided by poor and vulnerable delegates who are quick to sell their votes for peanuts.

And they sell their votes with the mistaken belief that they are reaping upfront their share of benefits from the democratic process, when indeed all they will achieve is a total surrender of their right to demand accountability from these elected officers while mortgaging Ghana’s future to charlatans, cabals – and sometimes to people involved in illegal and illicit businesses.

My view going forward is that, first, we should revisit the Constitutional Review undertaken during the Mills administration; then update it, given what we now know, and make the Constitution relevant to our current needs and promote good governance. Three specific areas of interest for me would be:

- Reviewing Section 70,

- Reconciling Sections 35 (7) and 36 (5) to promote shared purpose to focus on development and avoid waste, and

- Reviewing Section 47 clauses (1) and (5) to contain cost and build greater efficiencies

Additionally, every effort must be made to strengthen provisions dealing with the funding of political parties and campaign financing in the Political Parties Act 2000 (Act 574), in response to what are clearly red signs to the stability of our democracy.

Ghana’s Future Leadership Profile

Let me now turn to what Ghana’s future leadership mindset and profile should be, from my experience. I hope that from the analyses of Ghana’s needs in the short-, medium- and-long term we are now forming some pictures in our minds as to what kind of leadership Ghana needs today and into the future. The process cannot directly follow my private sector model, but we can and must adapt it to meet the demands of good governance. Before I go into the leadership re-profiling, permit me to make some general statements.

First, given my corporate experience, I believe that leaders are not born; leaders learn to lead. There is scientific evidence from neuroplasticity that refers to the brain’s ability to form new pathways and connections through exposure to novel, unfamiliar experiences. This allows adults to adapt, grow and learn new processes throughout our lifetimes. So, leadership is not a matter of inheritance or a matter of lineage; leaders are, and must be, developed.

Second, leaders are not necessarily the most intelligent, the most ambitious, the most eloquent; not the most vociferous, not the most charismatic and not those with the deepest pockets. These attributes may help, but they do not define good leadership. That is why in the private sector we have copious leadership development processes. My knowledge of the British political system, and most Western countries as well as Malaysia and Singapore, is that political parties do have clearly-defined leadership development programmes – and we can and must do the same. I will come to this later.

To build a great country in the medium- to long-term, I see that leadership in Ghana must make six fundamental mindset shifts to meet the short-, medium- and long-term needs of Ghana.

Our leaders must shift from being:

- Heads of State to Leaders with Purpose – (purpose pulls together vision, the

strategies to drive the purpose, commitment to the purpose and focused execution of strategies)

- Leaders to catalysts – (change-agents – long-termist, motivating and empowering

all stakeholders)

- Planners to Architects – (re-imaging and innovating, designing to build new

economic and social architecture fit for the new world economy),

- Controllers to Coaches – (enabling the country to constantly evolve and build

new mindsets, knowledge and skills)

- Bosses to Humans – (authentic servants, people-centred and pursuing inclusivity)

- Greedy and Corrupt to Honest and Socially Responsible – (leading with integrity,

working for all citizens while eschewing sectionalism)

These shifts will take time to achieve, maybe not in the short-term – even though I believe that if the political will is there, most of them could be achieved even in the short-term. In the medium- to long-term, however, there must be a determined effort on the part of the country’s leaders to achieve these shifts. I recommend that our political parties must define clear framework to clearly outline the profile of their fit-for-future leaders:

- Recruit, train, monitor and review the progress of identified future leaders, and

- Expose them to international best practices

Ghana needs leaders who build, not leaders who destroy; leaders who are rooted in today and tomorrow, not leaders who are rooted in yesterday and the distant past. According to Theodore Levitt of Harvard Business School, “Leadership is about tomorrow, not yesterday; but most leaders manage for yesterday’s conditions, because yesterday is where they got their experiences and their successes”.

Above all, Ghana needs leaders who are incorruptible, honest, transparent and credible; leaders with integrity, conscience and humility; leaders who will build an inclusive society. Standing in Ghana’s way, I’m afraid, is monitisation of the process for selection, election, appointment and vetting of leaders – from the Ward level to the level of the Executive and the Legislature. The process is woefully compromised.

But Ghana can learn from the advanced countries as well as from countries in South-East Asia, including Malaysia, Singapore, Taiwan, South Korea and recently Vietnam. Both Mahathir bin Mohamed (former prime ministers) of Malaysia and Lee Kuan Yew of Singapore, annually sent a minimum of 500 carefully selected high-potential future leaders to top universities all over the world, to study and acquire skills and capabilities for leadership positions in their countries.

On a visit to Malaysia in 2002, with President Kufuor, President Mahathir bin Mohamed told the Ghana delegation that he knew that about 50 percent didn’t return immediately to Malaysia, but he saw it as a good investment in Malaysia’s future governance.

So, the private sector template for leadership development (like Unilever) is possible and available elsewhere in the world; and the Ghanaian political parties must just borrow from it and stop putting into key leadership positions mediocre people who get to senior positions and only succeed in ruining our country.

Ghana has had a similar arrangement for a long time through the Scholarship Secretariat – set up during Dr. Kwame Nkrumah’s administration to do what the Singaporeans and Malaysians do. Sadly, the award of scholarships has also been politicised, and scholarships are now awarded to family members, friends and party supporters – and not only that but even worse, to people who sometimes are not even in any university.

I know I have spoken for a long time, but it is only because the issue of poor leadership in Ghana has been the major cause of our dire economic circumstances and the pervasive poverty to which our people have been subjected. It is unacceptable, and we must reverse our preference of mediocrity for the sake of party, family and personal relationships, and embrace merit and capacity as the only means to get into leadership. It has been too costly for Ghana, and we must reverse it. There will be no bright future for Ghana and no hope for our youth if we continue on the same track of putting selfish and parochial interests above national interests. And let me repeat to close – democracy is not only about the majority, it is even more so about values. The time is now or never.

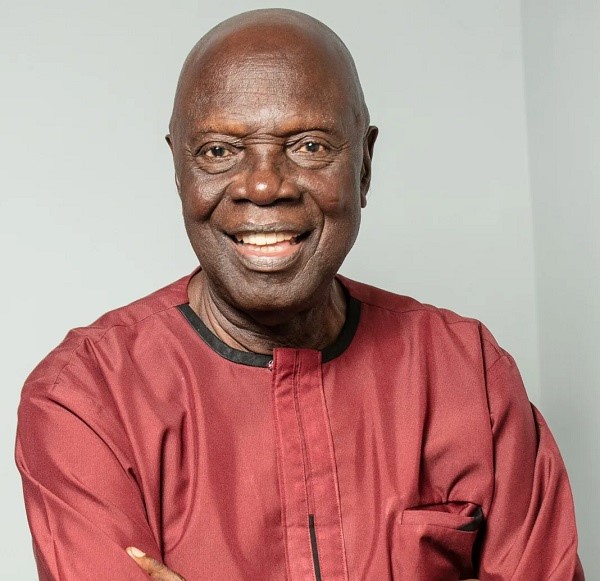

>>>the writer is the Founder and CEO of Yamson & Associates, a Business Development Consulting firm. He is also the non-executive Chairman of both Unilever Ghana Limited and Standard Chartered Bank, Ghana Limited. Mr. Yamson was the CEO of Unilever Ghana Limited for 18 years. During his tenure he transformed the company from a conglomerate business with interests in trading, power generation, motors, textiles and brewing into a focused, fast moving consumer goods company, with backward integration into major raw materials on an alliance basis.

He is now a founding and council member of the Centre for Policy Analysis and Chairman of the Governance Committee of the Commonwealth Business Council. Mr. Yamson has also served as President of the Ghana National Chamber of Commerce and Industry, President of the Ghana Employers’ Association and founding member and President of the Private Enterprise Foundation.

Prior to becoming Chief Executive for Unilever Ghana, Mr. Yamson spent 20 years working in senior management of Unilever companies in the UK, Holland and Africa. He held positions that include Chief Executive of Ghana Textile Printing/Juapong Textiles and of Gailey & Roberts in Tanzania, and Marketing Executive for the Kumasi Brewery and for Bird’s Eye Walls in the UK. He has a BSc. in Economics from the University of Ghana. He is married to Lucy with 5 children.

As a renowned leader and Chief Executive, Ishmael Yamson has received numerous local and international awards. Some of his honours include the Order of the Volta (Civil Division), Fellow of both the Ghana Institute of Marketing and Institute of Management, an Honorary Doctorate degree from the University of Ghana, Member of the Duke of Edinburgh’s Commonwealth Conference, and Honorary Member for the Global Coalition for Africa.