The need to prioritise the development of indigenous petroleum resources has become even more critical for two key reasons: the energy transition and energy security in a volatile energy market. Recent global geopolitical issues and energy trends teaches Ghana that lesson – to prioritise its God-given oil and natural gas resources to secure its energy requirements and transform the economy.

Domestic natural gas, for instance, is associated with an economic advantage – given that it sells for less than imported liquid fuels and gas, provides reliability and low cost for power generation and industrial use, and reduces the pressure on our local currency. Moreover, a thriving domestic oil and gas sector linked with industry creates millions of jobs and develops home-grown expertise among others.

Doric & Dimovski (2018) argue that energy resources provide the necessary facilitator for development of other sectors of the economy. According to the authors, when it comes to exploration and production of oil and gas, industrialised countries manage these resources in a way that assures the security of oil and gas company investments while decreasing a country’s dependency on imports; enabling better prices to industry and society in general, and having a positive impact on the state budget. That was exactly the expectation of Ghanaians when the country struck oil in commercial quantities and commenced oil production in 2010, beginning with 85,000 barrels per day (bpd) from the Jubilee field.

A decade after the commencement of oil production, a poor business climate, incoherent strategic petroleum plan, and inadequate policy support are accounting for under-investment in the upstream petroleum sector – leading to a consistent decline in the production of crude oil and under-utilisation of the country’s indigenous natural gas.

Declining Production Trends

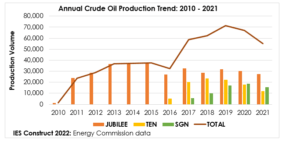

Data captured from the Energy Commission (EC) of Ghana show there has been an increase in oil production at an annual growth rate of 8.7 percent as of the end of 2021. However, over the last two years there have been constant declines in annual production volumes from the three offshore producing fields fields – Jubilee, Tweneboa Enyera and Ntomme (TEN) and Sankofa Gye Nyame (SGN), with 2020 and 2021 recording production falls of roughly 6.3 percent and 17.7 percent respectively from their preceding year’s production.

The Public Interest and Accountability Committee’s (PIAC) latest report shows a similar declining pattern, with the total volume for half-year (HY) 2022 from the three fields indicating a 6.9 percent decline from HY 2021 production. Thus, the PIAC report is suggesting a third consecutive reduction in year-on-year (YoY) crude oil production volumes since 2010. According to PIAC, the present decrease was a result of reduced production on the TEN and SGN fields, which recorded a decline of 34.3 and 21 percent respectively.

The Energy Commission’s data confirm that oil production from all three fields are showing signs of decline – Jubilee field started declining in 2016 from a peak of 102,498 barrels of oil per day (bopd) in 2015; whereas TEN started declining in 2019 from a peak of 64,541 bopd in 2018. An earlier report commissioned by PIAC and released in March 2022 indicated that production from SGN was projected to decline in 2021 from a peak of 51,232 bopd in 2020.

From all indications, total production from Ghana’s three fields has peaked and may experience continuous decline if nothing is done by way of new in-fill developments on these existing fields, or new fields coming on-stream.

PIAC attributes the decline in production volumes to technical challenges, such as poor well performance resulting in production losses from the Jubilee and TEN fields. It also included the delayed commissioning of gas processing and export infrastructure (gas management challenges), and stalled field developments as no new field has gone into production since 2017. The production declines have been occasioned even though Ghana has signed 18 petroleum agreements/contracts (PAs) covering its offshore basins since 2004.

Indigenous gas under-utilisation

Compounding the production decline challenge is the under-utilisation of indigenous natural gas – an issue that is rapidly transforming the gas sub-sector into a fiscal burden for the country. The situation is the result of poor demand growth, poor energy strategies, and delay in building the requisite infrastructure to off-take the processed gas, in the face of ‘take-or-pay’ clauses in gas contracts.

Records from PIAC show that over the last 8 years less than half of the country’s produced gas was utilised for power generation and non-power activities, with the remaining gas either re-injected or flared. For instance, in 2021 of the 256,262 million standard cubic feet (MMscf) of raw gas (associated and non-associated) produced from the three producing fields (Jubilee, SGN and TEN), just 98,900 MMscf (38.6percent) was transmitted during the year to Ghana National Gas Company (GNGC) and the Onshore Receiving Facility (ORF) from the fields. Ironically, the re-injected gas constitutes 48.0 percent, while total gas flared was 8.3 percent of total produced gas.

This shows that re-injected and flared gas constitutes a significant (56.3 percent) portion of the total gas produced from the three fields. This makes it abundantly clear that the country has excess natural gas, hence the decision to re-inject and flare.

Ghana may be one of the most gas-resourced countries in West Africa but the country is facing the real possibility of reliance on imported natural gas, driven by government’s misplaced priorities in the gas sub-sector. Despite its vast natural gas potential, Ghana has failed to maximise the utilisation of its gas – rather choosing to import gas from abroad to the disadvantage of its indigenous gas resource, and exploration and production (E&P) companies.

Instead of the state giving priority to the production and off-take of indigenous gas, it has rather resorted to gambling on the importation of liquefied natural gas (LNG) without giving a thought to the guarantee of sufficient and reliable supply of same. Government’s appetite for natural gas imports in the form of LNG can best be described as short-sighted, morally indefensible, naturally irresponsible, and a deliberate attempt to increase the fiscal burden on the economy.

It is not too late, though, to rethink its decision to import natural gas from overseas at the expense of its vast natural gas resource. Given the country’s vast gas reserves and the capability of existing contractors to meet the gas needs of the country, the state is better off prioritising gas liquefaction instead of regasification. It is worth repeating that “the contracting of a regasification facility at this moment is misplaced and wasteful” – in the sense that it is going to create excesses of supply, resulting in cost to the country.

Role of Policy Certainty

Ben-Gera (2006) defines policy as a “course of action or inaction chosen to address a given problem or interrelated set of problems, or the way in which the courses of action for achieving the appropriate goals are determined”. It includes but it is not limited to taxation, regulation, expenditures, information, statements, legal requirements and legal prohibitions.

In the energy space, Shaffer (2011) finds that countries throughout the world use energy policy to achieve geopolitical and economic advantages, and to position themselves globally. In Egypt for instance, enabling domestic policies laced with certainties and a robust investment framework for the broader oil and gas industry are helping to ramp up upstream exploration and production that will ultimately position the African country as a regional player.

Even in the face of the energy transition, The Oxford Business Group observed that Egypt between 2015 and 2020 has attracted financing of roughly US$74billion from government agencies and international oil companies (IOCs). On the back of the huge investment, Mordor Intelligence has forecasted Egypt’s upstream oil and gas market to expand at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 8 percent between 2019 and 2027.

To deal with Ghana’s dwindling oil production and the under-utilisation of indigenous natural gas, the present administration must emulate the likes of Egypt and start addressing issues bordering on its investment framework by developing coherent and favourable policies to attract investment into the broader petroleum industry.

There is a need for policies and actions which provide certainty, assures inclusiveness and improves predictability. Once policy certainty is in place, the market will react by providing the requisite investments in response to market attractiveness, which will bring back the much-needed confidence in the upstream petroleum sector.

In shaping the policies, government must capture well-defined supply-demand dynamics and priorities in consultation with industry players. Broad consultation with and consideration of the views of industry players in framing policies and regulations which govern the upstream sector will generate some form of settlement and certainty for policies. It has been found that the lack of consultation between government agencies and investors is the reason for today’s fragmented policies (particularly for the gas sub-sector), the reason for failure to attract necessary investment for the upstream sector.

Over the past years, operators of Ghana’s existing producing fields have given all indications that they can and are willing to increase, significantly, the current production levels through additional investments, given the needed support and cooperation from government. All that’s required is government’s willingness to remove constraints imposed on the sector, expedite action on the signing of new petroleum agreements (PAs), and provide policy certainty.

Some level of urgency in resolving differences government may have with existing investors is equally necessary to enable contractors expedite action on expanding existing fields, to either sustain or grow production levels.

Furthermore, government must stay committed to the terms of existing PAs. Any attempt by the state to disregard, for instance, the stabilisation clauses in PAs threatens that predictability for investors in recouping their investments at reasonable returns. Fabrizio (2012) argues legal uncertainty increases the fiscal risk to investments, thus reducing the opportunity to grow investment in existing fields – and is damaging host country’s reputation.

>>>the writer is Director of Research & Finance, Institute for Energy Security (IES) ©2022. Email: [email protected]