The 2022 Economic Development Report on Africa has underscored the fact that diversification of African economies is the most viable strategy for Africa’s economic prosperity in the global economy. The Report is titled ‘Rethinking the Foundations of Export Diversification in Africa: The Catalytic Role of Business and Financial Services’.

The Report notes that though Africa has the highest concentration of exports compared with other world regions, it has the second-lowest number of exported products after Oceania. Similarly, trade in services within Africa is both low and heavily dominated by traditional services. Potentially, however, high-knowledge-intensive services and technology-enabling services have the potential to boost innovation and drive diversification.

The Report proposes strong policy-oriented actions to help Africa leverage trade in services, and to diversify economic activities into new and potentially transformative sectors. According to the Report, Africa’s export diversification potential must be linked to the catalytic role of firms and financial services, which must be underpinned by capable, inclusive and accountable institutions.

Unmet financial needs

Currently, there are about 50 million formal microenterprises and small and medium-sized enterprises in Africa, with an unmet financing need of US$416billion every year. Some of these exporting firms, particularly new entrants and small-scale exporting firms, need to secure external financing to cover the high cost of entering into export markets. These SMEs represent the bulk of private enterprises on the continent. The Report highlights credit constraints and the need to facilitate access to financial technology that is critical for the growth and competitiveness of small and medium-sized businesses.

Hopefully, the African Continental Free Trade Area (ACFTA) coming into force gives African countries a unique opportunity to promote trade in services, export diversification and regional value chain development. Therefore, high-knowledge-intensive sectors and financial services should be mainstreamed into national and regional export diversification strategies, by drawing on internal and external knowledge and expertise in the public and private sectors.

Furthermore, national development and regional integration policies should provide specialised financial and non-financial products and services – such as government loan guarantees and pool risk instruments – that can better help address the long-term financial needs of small and medium-sized enterprises. Moreover, the establishment of regional payment systems, legislating regional policies and convergence in the regulation of innovative financial technology are required to catalyse financial technologies.

Also, African governments are required to strategically design and target incentives that encourage entrepreneurs to move into economic activities with the potential to drive structural change in their economies.

A massive 83 percent of African countries are commodity-dependent. These countries also constitute 45 percent of commodity-dependent countries worldwide, notes the report. According to UNCTAD, a country is commodity-dependent when its share of primary commodity exports is more than 60 percent of its total merchandise exports.

To change the situation, African governments need to initiate policies and investment agreements which ensure skills-transfer, technological know-how and innovation in partnership with the private sector. Governments also need to mobilise domestic resources to provide targetted infrastructure and technology that promote industrialisation. In short, the Report makes a clarion call for Africa countries to diversify from commodities into knowledge-intensive services. In this light, the One District One Factory industrialisation drive of the Ghana government is a prudent policy worth every support.

Fintech on an upswing

The Director of UNCTAD’s Division for Africa, Mr. Paul Akiwumi, in an interview with UN Africa Renewal affirmed that small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in financial technology (fintech), agri-tech, health-tech and other high-knowledge-based and technology-driven SMEs can help the continent achieve financial and social inclusion.

Therefore, Africa must diversify into knowledge-intensive services to achieve the twin goals of ‘providing support for existing traditional economic activities’ and ‘creating innovative products that will boost productivity’, he insists. Mr. Akiwumi further explains that small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in fintech, agri-tech, health-tech and other high-knowledge-based and technology-driven SMEs can help the continent achieve financial and social inclusion.

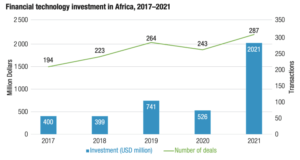

The good news is that investment in fintech in Africa is on an upswing. UNCTAD reports an increase of investment in the sector from US$400million to over US$2billion between 2017 and 2021. And Mr. Akiwumi projects the figure could reach US$4billion by the end of 2022.

The UNCTAD report praises Opay – a Nigerian point of sale platform and mobile payment service company – as a top performer in fintech services. In 2021, Opay raised US$400million and currently boasts 160 million users, including millions in the huge unbanked population.

Hurdles in the way

“We have fintech fostering the financial inclusion of people, so we don’t need a physical bank anymore. They can manage their accounts in their apps,” says Akiwumi. Despite such progress, hurdles remain in the way. The report lists “restricted access to finance, poor integration in regional and global markets, and a limited skills base” as some of the roadblocks to financial inclusion. For example, mobile money – the most-used financial technology in Africa – is only being utilised to advance short-term microloans to users, states the report.

Mr. Akiwumi says the onus is first on governments to provide the right environment, including cyber security, since most transactions are electronic. Besides, there’s a need for adequate power supply, since there can be no development without reliable and sustainable power supply. Furthermore, Internet infrastructure and its regulatory frameworks have become critical for both financial service and business development.

Moreover, there is a need for governments to enable the private sector to play a lead role in financial sector service delivery. According to the report, financial technology and alternative financing are mostly private sector-driven, which could boost export diversification if appropriate legal and institutional frameworks are in place.

AfCFTA is a catalyst

Several experts have spoken about the African Continental Free Trade Area’s (AfCFTA) potential to consolidate a market of about 1.2 billion people. “Potentially, Africa’s market is a huge potential for export diversification,” the report notes. It is therefore expected that AfCFTA will ease business transactions and help countries to “prioritise services sectors that are relevant to a value chain relevant for a given country”. Experts are forecasting that a smooth AfCTTA could to a transformed African economies ten years from now.

Protectionism

With AfCFTA in full swing, experts are divided on the issue of protectionism. For example, Carlos Lopes – a former Executive Secretary of the UN Economic Commission for Africa – once argued for what he termed “sophisticated protectionism”, which is a government’s strategic intervention with policies that target specific sectors to benefit the national economy. However, Mr. Akiwumi counters with: “Protectionism only gets countries less prepared for competition. There must be competition, and competition leads to efficiency and cost-effectiveness”. He argues that protectionism stifles innovativeness and the ability to absorb new technologies, though he is not against policies which protect sectors pertaining to national security.

Slow transition

A major factor responsible for Africa’s slow transition to emerging economy status is that the current commodity development and import-dominated models have in no way transformed Africa’s economic structure. This trend further explains why Africa’s weak economies cannot stand global economic shocks. According to UN statistics, over the last 40 years only six countries have graduated out of the least developed counties (LDCs). The six countries are: Botswana in 1994, Cape Verde in 2007, Maldives in 2011, Samoa in 2014, Equatorial Guinea in 2017, and Vanuatu in 2020.

The 46 current LDCs comprise around 880 million people – 12 percent of the world population. These LDC countries face severe structural impediments to growth, account for less than 2 percent of world GDP and around one percent of world trade. The 46 countries currently on the list of LDCs include:

Afghanistan, Angola, Bangladesh, Benin, Bhutan, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cambodia, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gambia, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Haiti, Kiribati, Lao People’s Dem. Republic, Lesotho, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mozambique, Myanmar, Nepal, Niger, Rwanda, Sao Tome and Principe, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Solomon Islands, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Timor-Leste, Togo, Tuvalu, Uganda, United Republic of Tanzania, Yemen and Zambia. Sadly, most LDCs are African countries.

In the late 1960s, the United Nations began paying attention to the least developed countries, recognising those countries as most vulnerable among the international community. The International Development Strategy for the second UN Development Decade for the 1970s incorporated special measures in favour of least developed countries.

The category of least developed countries (LDCs) was officially established in 1971 by the UN General Assembly, with a view to attracting special international support for the most vulnerable and disadvantaged members of the UN family.

The first United Nations Conference on LDCs was held in Paris in 1981, during which a comprehensive Substantial New Programme of Action for the 1980s was adopted. Similar conferences on LDC were held in 1990 in Paris and Brussels in 2001.

In 2008, the General Assembly convened the Fourth United Nations Conference on Least Developed Countries (LDC-IV). The same conference was held three years later in 2011 – Istanbul, Turkey – to assess the Brussels Programme of Action’s implementation by LDCs and their development partners. The 5th United Nations Conference on LDC5 was held in Doha in January 2022 to help build a new programme of action for LDCs. The conference was held at a critical time when action for the 2030 agenda gathers pace.

Despite the numerous conferences on LDCs, these poor countries (most of them African) continue to face major obstacles that block their sustainable development, said Paul Akiwumi, UNCTAD’s director for Africa and least developed countries. These include soaring debt, export marginalisation, energy poverty and climate vulnerability. LDCs also remain marginalised in global trade. Their share of global merchandise exports has hovered at around just 1% since 2010. And their main exports leave them highly vulnerable to global crises and shocks.

As many as 38 LDCs remain commodity-dependent, relying on primary goods like copper, cotton, cocoa and oil for over 60% of their merchandise exports. Besides, global commodities’ markets are very volatile – and when prices crash, so do exports, jobs and government revenue. This volatility is a serious threat to many LDCs, especially for food and fuel. All persistent pressure on LDCs to devalue their currencies continues to undermine labour and manpower development.

All said, the unfair global economic order continues to undermine LDCs, especially African economies. For instance, it is well-documented that France siphons over US$500billion from its former colonies (all LDCs) each year under an obnoxious colonial pact. Why has the UN kept quiet over this injustice and pillaging of African resources? When Will Africans and Africans in the Diaspora say enough is enough to the pillage of African resources?

Reference

United Nations. 2022. Rethinking the Foundations of Export Diversification in Africa: The catalytic role of business and financial services