Inflation, which refers to the rise in prices of goods and services, affects everyone. That notwithstanding, some people are oblivious to its direct impact on our lives. This brings to the fore a phenomenon called ‘Money illusion’ – which is the tendency to view income and wealth in nominal terms instead of their inflation-adjusted values.

Both individuals and institutions are affected by inflation, but worst-hit of the lot are pensioners because their income is often not adjusted to inflation. Beneficiaries of rising inflation are predominantly borrowers, as rising inflation decreases the real value of their debts.

Inflation has varying impacts on a private investor. This further varies from one investor to another, mainly due to how soon their income is adjusted to inflation. Pensioners tend to bear more of the impact from rising inflation because the income received during retirement is often fixed at a nominal value for a period of time, unlike the working public which has their salaries adjusted to inflation from time to time in the form of salary increments.

Assuming a pensioner is expected to live about 15 years after retirement, with annual inflation of about 10 percent the pensioner’s purchasing power is likely to decline by more than 100 percent, assuming there are no adjustments to the pension being paid. The pensioner therefore has no guarantee of protection against inflation.

Some traditional asset classes provide some degree of protection against inflation. These include equities, gold and real-estate. The protection these assets offer against inflation is not enough to accommodate its full impact. On the other hand, Inflation-Linked Bonds (ILBs) have been seen to be reliable and consistent in containing the impact of inflation and also providing positive real returns in a portfolio.

The first ILB was issued by the state of Massachusetts in 1780, with cash flows of the bond being linked to the prices in a representative basket of consumer goods. The UK then became the first industrialised nation to issue such a bond in 1981. The US and Germany issued theirs in 1997 and 2006 respectively. The total market value of ILBs stands at an estimated US$2.4trillion, with 13 of the world’s largest economies active on the ILB market. Brazil currently dominates the emerging economies’ market for ILBs, with a market share of over 70 percent.

How inflation-linked bonds work

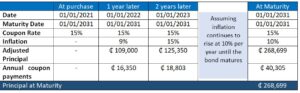

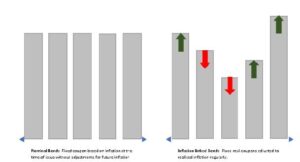

The nominal bonds that are issued are done with a fixed nominal coupon and a principal amount agreed upon in advance of the bond’s maturity. At the time of issuance, these bonds take into account prevailing inflation at that time but are not adjusted over the bond’s lifetime. On the other hand, ILBs offer a guaranteed real return irrespective of the level of inflation.

The structure of ILBs provides investors protection against rising inflation. These ILBs can be set up in two ways to counterbalance the effects of inflation after they have been issued. The first setup can have coupons that are adjusted in line with the level of inflation while the principal remains constant.

The second option can have the principal amount regularly adjusted by the latest inflation rate, while the coupons are pegged at a percentage of this adjusted value. Although the coupon rate remains fixed because the coupons are paid on the inflation-adjusted principal value, the nominal value of the coupons paid rises over time – which effectively links the coupon to inflation as well.

The value of an ILB moves up and down after it is issued and listed, which is expected like any other security because these movements are in response to changing market conditions and sentiments. The price of such a security is sensitive to movements in inflation and interest rates. ILBs can suffer during low inflation and periods of slow economic growth, as their prices tend to decline as yields rise.

Aside from the benefits of offering protection against inflation, ILBs can be used as good security for diversification in a multi-asset portfolio because of their low correlation to other asset classes. ILBs have a low tendency to move in the same direction as equities and nominal bonds, and therefore lower the overall volatility of a portfolio.

Interest rates on nominal bonds are made up of real interest, expected inflation and an inflation risk premium that offsets the risk of realised inflation being higher than the expected interest rate. ILBs do not include inflation premiums because this type of risk is nonexistent in such bonds. Because of this, the yields on ILBs tend to be lower yet provide the best option for protection against inflation.

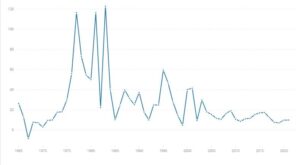

Does Ghana have the right market environment for Inflation-linked Bonds?

The value of nominal bonds is determined by changes in interest rates and inflation expectations, but ILBs change with the fluctuation of real interest rates. Assuming inflation expectations remain constant, there will be no difference in the returns generated by nominal bonds and ILBs. Changes in returns between these 2 classes of bond can solely be attributed to changes in inflation expectations. A rise in expected inflation will mean that ILBs outperform nominal bonds and vice-versa. These are the key indicators as to whether an ILB will generate higher returns than nominal bonds.

The demand for ILBs typically comes from pension funds and asset managers, though recent data show retail investors are developing an appetite for these bonds.

With the current inflation above the central bank’s inflation target of 8±2, data from analysts suggest that in periods of inflation staying above this target, 10-year ILBs are likely to outperform their nominal bond peers – with data on the last 20 years and in different eras supporting this analysis.

How does the Bank of Ghana benefit?

Issuing ILBs not only benefits investors but also the central bank. The Bank of Ghana benefits from the inflation risk protection by ILBs, and also makes savings on its interest expense. The central bank, which is the largest issuer of nominal bonds, bears a high degree of inflation-risk when servicing its debt.

In the current dispensation of high coupon rates on bonds, which is a result of the increasing inflation, assume that a five or 10-year nominal bond is issued during this period with a likely coupon rate of 30 percent to 35 percent. In the next two years, when inflation drops to about 10 percent, the central bank will still be paying the high coupons of the bonds that were issued during periods of high inflation. This will increase the cost of servicing the debt. The above notwithstanding, if all outstanding debts of the central bank were indexed to inflation the cost of debt servicing would not vary inversely with inflation.

ILBs save the central bank some amount of money by eliminating the embedded inflation risk premium embedded in the yield of nominal bonds. The inflation risk premium compensates the investment for exposure to inflation risk. Because ILBs do not carry any inflation risk, their nominal yields do not contain any premium for inflation risk. The cost of ILBs tends to be lower by the size of the inflation risk premium.

Thus, by issuing ILBs instead of nominal bonds the central bank would, on average, save money by eliminating any inflation risk premium that might exist. Although the inflation risk premium for nominal bonds is uncertain, ILBs would save the Ghanaian taxpayer a great deal of money because of the large scale of borrowing done by the central bank.

How do policymakers benefit?

Policymakers benefit from ILBs by gaining information on real interest rates in addition to inflation expectations by the market. The availability of a liquid market will provide a lot of information on real interest rates. A nominal bond comprises the sum of the real interest rate, expected inflation and inflation risk premium. Therefore, the difference between the rate of a nominal bond and rate of an ILB becomes the sum of expected inflation and the inflation risk premium. If the inflation risk premium remains constant over time, changes in rates of nominal bonds and ILBs reflect the changes in expected inflation by the market. Without data from the above, policymakers will not be in a position to tell whether the decline in nominal rates is a result of improved inflation or changes in real rates.

In the absence of data on real interest rates, policymakers will have to rely on statistical models or surveys to make estimates of inflation expectations. These methods of estimation are subordinate to estimates received from market data on nominal bonds and ILBs, because data on government bonds are available as soon as a trade occurs and reflect the true belief of investors as backed by their money.

The data also become available to monetary policymakers, as information on expected inflation helps them to better understand inflationary pressures on the Ghanaian economy – which will allow them to make necessary adjustments to the monetary policy from time to time.

In addition to this, the data become useful to businesses which are likely to raise prices of goods and services if they perceive inflation will be higher; and consumers are also likely to accept these higher prices if they perceive the increases to be consistent with the general inflation rate. This will enable the policymakers to detect increases in inflation expectations and take the necessary steps to effectively counter the changes.

Issuing ILBs strengthens the credibility of low inflation policies. Because ILBs cannot be inflated away, there is a low motivation for politicians to generate inflation for the purposes of reducing the debt burden of government.

“Many people want the government to protect the consumer. A much more urgent problem is to protect the consumer from the government.” —Milton Friedman

The author is a Senior Research and Compliance Analyst at Tesah Capital

He can be reached on 0201653697 and at [email protected]