In the year 2020, Ghana and Ivory Coast leveraged their cocoa production dominance to capture some extra value i.e., the Living Income Differential (LID) levy that granted cocoa farmers $400 extra income for a metric ton of cocoa beans sold. At the back of this is what was referred to as “COPEC”, the Cocoa sector’s version of “OPEC”, as a potential cartel that can protect the interest of cocoa-producing countries.

In this article, I will assume “COPEC” as the working name for an organisation of cocoa-producing countries. I will argue that “COPEC” should work “with” not “for” politicians and Lead firms with a business-biased interest in the cocoa value chain, to alleviate cocoa farmers from endemic poverty. I will give an overview of OPEC and argue that it was formed at the “Right time” hence made the organisation impactful and relevant to its mission to protect their interest from those of the western oil marketing firms.

I will juxtapose this onto the cocoa sector and highlight how COPEC though sounds like a good idea will have less impact as compared to if it was formed during the 1950s after Independence. I will conclude with some policy recommendations that can make “COPEC” an impactful cartel that can flip the script and fairly protect all the actors in the cocoa-chocolate value chain, especially the Smallholder Cocoa Farmer.

OPEC (ORGANISATION OF PETROLEUM COUNTRIES)

OPEC countries, for example, were a victim of the natural resource exploitation due to the economic, financial, and technological power Western Oil Companies (WOC) had over them. WOC used this power to exploit the Crude Oil of the now OPEC and locked them out in even having a say in the price of Crude Oil until the formation of OPEC.

WOC invested in the oil exploration on the lands of OPEC, vertically integrated that upstream sector to their existing downstream networks and became dominant in the oil industry. They took charge of price setting and set prices of crude oil very low so that they can buy it cheaply for refining into more valuable products like gasoil, gasoline, etc., in their refineries in their home country (outside of OPEC).

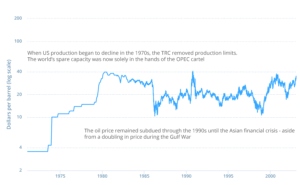

This exploitation continued for years and heavily affected the economic growth of OPEC countries as 90% to 99% of their foreign exchange came from crude oil exports in the 1960s. OPEC realized they were supplying over 70% of the global oil needs during the industrial revolution from the 1970s and sensed the long-term global dependence on oil as a necessity product. Realising this opportunity, they came together as a strong unit, took over the control of the entire activities within the upstream sector including the unilateral setting of prices of crude oil and the distribution of oil concessions, hence the formation of OPEC.

They unilaterally increased crude prices by an estimated 40.25% and further by an estimated 127.6%. This exchange and utilization of power from the WOC to OPEC saw OPEC increasing its balance of trade surplus from $8bn in 1973 to $114bn in 1980. Europe and United States on the other hand recorded a balance of trade losses of 42.6% and 29.3% respectively within that same period. This can be argued as a fair redistribution of value within the Oil & Gas value chain for the benefit of OPEC.

Graph 1: 1971 – 2003: OPEC Takes Over From TRC

COMPARING THE COCOA SECTOR TO THE OIL SECTOR (OPEC)?

Since the 1900s the OPEC countries were exporters of unrefined Crude Oil (raw Materials). Crude Oil was explored by the buyer (the oil marketing companies) on the land of OPEC as they had the technology, technical know-how and financial strength. The success of the OPEC countries in their ability to claim and control prices was due to the high dependence on Oil & Gas for industrialisation and the almost non-existence of substitutes. This rendered the oil marketers powerless yet had to still consume the products at any price thrown at them by OPEC.

The high prices led to the rise in exploration and discovery of crude oil, the development of energy-efficient machines, and substitute energy products, hence stabilising and driving down prices. But at this point, most of the OPEC countries have made a lot of money and some, smartly diversified from oil to reduce the economic risk with the downward trend in oil prices.

On the other hand, Cocoa is cultivated by experienced smallholder cocoa farmers with the technical know-how and have access to local technology needed for cocoa production. Though Chocolate, the main derivative of cocoa beans, may not have been a necessity good like oil, its annual demand growth is directly associated with the growth of the middle class which is also associated with the rise in the industrialisation era.

So, one can establish a parallel between the rise of industrialisation with the rise in the demand for oil and chocolate due to middle-class growth. So, whereas OPEC was formed in the 1970s to take advantage of the Industrialisation era, Dr Nkrumah (Ghana’s first President), who wanted to form a cocoa cartel in the 1960s even before the formation of OPEC, to take advantage of prices at that right time, was overthrown. So, the Concrete silos that were built to facilitate the supply control of Africa’s cocoa production, were never used and still surviving at Tema, Ghana.

The period between the 1960s till today was the prime opportunity for us to extract as much value as possible through price controls since we were raw-materials export-focused. Today is the right time for us to be diversifying rather than price-fixing.

This is because the lead firms have already found means on controlling cocoa beans price i.e., through hoarding, financing NGOs to encourage more cocoa production. They have vertically and horizontally integrated such that we have 4 companies processing over an estimated 74% of the world’s cocoa beans.

Lead firms backward and upward integration, and heavy utilisation of technology due to their strong economic strength in investing in research and development, increase their competitiveness, economic & political power and dominate the value chain’s governance. Whereas price-fixing may disadvantage lead firms in terms of the rise in their input cost, it auto protects them from the competition as price hikes increase barriers to market entry, especially indigenous investors.

Some of these lead firms are already investing in commercial farming outside of Africa to reduce their reliance on Ghana and Ivory Coast, hence creating a geopolitical tension that pit producing countries against each other. Lab-grown chocolate has also emerged.

This is synonymous with the oil sector where a rise in crude oil prices rather inspire innovations and more oil exploration that rendered price-fixing myopic. But in this cocoa sector, the one who suffers from Price fixing is the Cocoa Farmer rather than the government or Ghana Cocoa board.

So, the question remains, is COPEC an effective tool today? To whom is this potential cocoa cartel COPEC supposed to benefit? How resilient can it be in a hyper-governed industry, and how can we ensure that it delivers a sustainable increase in value extraction for smallholder cocoa farmers? How will COPEC ensure local value addition and the competitiveness of the indigenous cocoa processor/chocolate manufacturer with its price-fixing? I am concerned about Smallholder cocoa farmers.

Remember that the government’s interest in the cocoa sector hasn’t always been for the supposed benefit of the cocoa farmer. For example, after independence, foreign exchange earnings from Cocoa were heavily used to pursue Dr Nkrumah’s import Substitution Industrialisation agenda at the expense of the cocoa farmer’s livelihood. He and successive governments paid cocoa farmers less than Gh¢1 for a ton of cocoa beans while receiving a world market price of between US$389.00 and US$ 3,632 per ton between 1950 and 1980 (See Fig 1 & 2).

In effect, for 50 years since 1950, Ghanaian Cocoa Farmers were made to work as slaves for an estimated 80% to 100% tax by both the Colonialists and our governments. This is the source of the endemic poverty among cocoa farmers. The difference between OPEC and COPEC is the estimated 2,000,000 Smallholder Cocoa Farmers in producing countries.

Whereas the Nkrumah’s government saw Cocoa as a financialised commodity whose foreign exchanges was worthy of being used unilaterally for his import substitute industrialisation agenda, it came at the short-term and long-term economic and social cost for cocoa farmers. To understand this, imagine a tomato farmer and a cocoa farmer in Ghana.

The tomato farmer can produce and sell their products and receive the whole money directly. However, Cocoa farmers sales pass through a government entity that pays the cocoa farmer less than Gh¢1 for a product they sold for $3,632. And the government gives you the cocoa farmer an excuse that your products (Cocoa), fortunately, brings in foreign exchange and I need that foreign exchange to industrialise the economy.

Any Window of opportunity with “COPEC”

From the learnings from OPEC and other industries, leveraging your raw material production strength to implement price control, is a strategy that would have been effective from the 1950s. Every for-profit business needs to find ways to reduce its cost of production. So, I do not begrudge any value addition firm that innovatively convert a suppliers’ market into a buyers’ market.

I will rather begrudge regulatory agencies and government who are not two steps ahead of lead firms to ensure that their activities do not render smallholder cocoa farmers endemically poor, increase barriers to market entry for local actors or render Cocobod’s operations unsustainable. Below are some policy recommendations for COPEC if it finally gets formed:

- COPEC’s mission should be Smallholder Farmer livelihood-focused with clear objectives on how their activities will directly increase the net income of the smallholder cocoa farmers rather than meeting a political objective that has no direct link to a measurable livelihood improvement of smallholder cocoa farmers.

- COPEC should develop a cocoa land acquisition and management policy that prevent businesses from buying lands from cocoa farmers for commercial cocoa farming with some fake assurance of employing the farmers back. The land is the only appreciable livelihood asset that can pass on as economic insurance to their children.

- COPEC should have a cocoa interventionist policy that prevents cocoa value addition firms who embark on any programme that is intended to increase cocoa production excessively.

- COPEC countries should operate an incentive policy that increases the competitiveness of indigenous investors who would like to enter the cocoa processing and chocolate manufacturing sector.

- COPEC should embed value addition to its agenda and remove any impediment that prevents indigenous investors from investing in the sector. For example, why should being a member of the Federation of Cocoa Commerce in London be a prerequisite to gaining a beans supply agreement as an indigenous investor? Having more indigenous-owned value-adding firm increase COPEC’s power in the value chain.

- COPEC should design a diversification roadmap that helps cocoa farmers to transition into the production of other crops. This will diversify cocoa farmers’ income source reduce their economic risk of being reliant on just the proceeds from cocoa farming. The well-known investment advice is to always diversify your portfolio to spread risk. Cocoa farmers’ diversifying part of their lands into other crops keeps a supply in check to maintain high cocoa prices. The diversification should be intensified when lead firms devise strategies to be resistant to the prevailing supply numbers.

- COPEC should finally behave as a vigilant unit and a better regulator that is not hostile to cocoa value addition firms but rather keeps both governments and lead firms in check to ensure that their activities do not directly or indirectly, keep rendering cocoa farmers poor. Investment in Research & Development and Business intelligence unit is crucial.

Kwame Asamoah Kwarteng is an International Development & Trade Analyst with a deep research interest in issues affecting smallholder cocoa farmers in Ghana

Twitter: @asamoahpeters

LinkedIn: Kwame Asamoah Kwarteng”