The tech industry is at a crunch point.

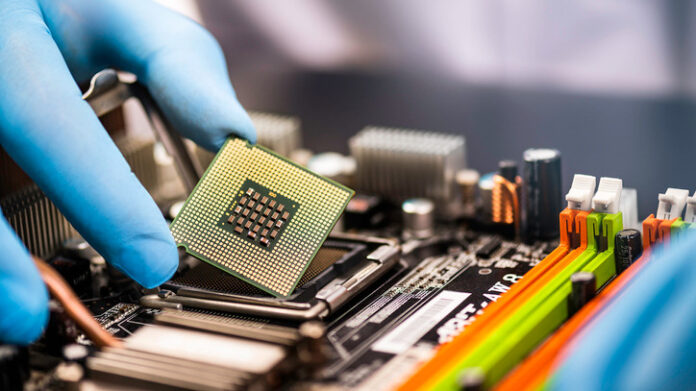

Today, millions of products – cars, washing machines, smartphones, and more – rely on computer chips, also known as semiconductors.

And right now, there just aren’t enough of them to meet industry demand. As a result, many popular products are in short supply.

It has become almost impossible to buy a PS5 games console. Toyota, Ford and Volvo have had to either slow or temporarily halt production at their factories. Smartphone makers are feeling the pinch too, with Apple warning that the shortage could affect iPhone sales.

Even companies that wouldn’t necessarily be associated with computer chips haven’t been spared, such as CSSI international, a US firm that makes dog-grooming machines, is feeling the effects.

Some shoppers have already noticed these problems. Sales of used-cars are up, for instance, because new vehicles, often packed with thousands of individual chips, are in short supply.

Kris Halpin, a musician based in North Warwickshire, is one of many who have experienced disappointment. Mr Halpin has cerebral palsy and leases a car through the Motability scheme.

His current lease ends in October and under the rules of the scheme he must replace his car at that time. However, his local dealership has told him that the car he ordered has been delayed until January next year at the earliest.

“As a disabled person I am really, really reliant on my car,” says Mr Halpin, who uses a wheelchair. “Where I live, I literally couldn’t get beyond my drive without my car.”

Thankfully, Mr Halpin says that Motability agreed to extend the lease and insurance on his current car until the new one arrives.

In the coming months and, particularly over Christmas, it’s possible that even more products will fall foul of the shortage.

So, what is going on?

The chips that are in short supply perform various functions in modern products, and there are often more than one in a single device.

Piotr Esden-Tempski is the founder and owner of 1bitsquared, a US-based firm that specialises in electronics hardware. He has orders on his books for several thousand electronics interface boards, which allow students and makers to connect various appliances to their computers.

But Mr Esden-Tempski’s suppliers say that some of the components he needs containing semiconductors will not be available for 12 months or more.

“You cannot just assemble it and miss one part, it won’t work,” he says.

This situation has been developing for years, not just months.

Koray Köse, an analyst at Gartner, says that among the pressures facing the chip industry prior to the pandemic were the rise of 5G, which increased demand, and the decision by the US to prevent the sale of semiconductors and other technology to Huawei. Chip makers outside the US were quickly flooded with orders from the Chinese firm.

Other, less obvious, manufacturing complexities have also hampered the supply of certain components.

For example, there are two main approaches to chip production right now: using 200mm or 300mm wafers. This refers to the diameter of the circular silicon wafer that gets split into lots of tiny chips.

The larger wafers are more expensive and are often used for more advanced devices.

But there’s been a boom in demand for lower cost chips, which are embedded in an ever-wider variety of consumer products, meaning the older, 200mm technology is more sought after than ever.

Industry news site Semiconductor Engineering highlighted the risk of a chip shortage, partly due to a lack of 200mm manufacturing equipment, back in February 2020.

As the pandemic unfolded, early signs of fluctuating demand led to stockpiling and advance ordering of chips by some tech firms, which left others struggling to acquire the components.

People working from home have needed laptops, tablets and webcams to help them do their jobs, and chip factories did close during lockdowns.

At times consumers have struggled to buy the devices they want, though manufacturers have so far been able to catch up with demand eventually.

Mr Köse says, however, that the pandemic was not the sole cause of the chip shortage: “That was probably just the last drop in the bucket.”

More recently, bad luck has exacerbated the problem. An atrocious winter storm in Texas shutdown semiconductor factories, and a fire at a plant in Japan caused similar delays.

Logistical headaches are compounding the situation. Oliver Chapman, chief executive of OCI, a global supply chain partner, says that for many years the cost of shipping was not of great concern for many tech firms because their products are relatively small, and suppliers could fit lots of them inside a single 40ft container.

But the cost of moving shipping containers around the world has ballooned because of sudden shifts in demand during the pandemic. It is accompanied by a rise in air freight fees and the lorry driver shortage in Europe.

Sending a single 40ft container from Asia to Europe currently costs $17,000 (£12,480), says George Griffiths, editor of global container markets at S&P Global Platts.

That’s a greater than ten-fold increase compared to a year ago, when it cost around $1,500 (£1,101).

Chip makers are responding to sustained demand by increasing capacity but that takes time, says Mr Köse, not least because semiconductor factories cost billions of dollars to build. “That is not going to be solved by this Christmas and I find it hard to believe it will be solved by the next Black Friday [November 2022],” he says.

Bosses at the tech giants appear sharply aware of this. The chief executives of Intel and IBM have both said recently that the chip shortage could last two years.

Seda Memik, professor of electrical and computer engineering, and computer science, at Northwestern University, agrees: “It will take multiple years to accomplish… a better balance.” She also says that the pace of demand for chips has been rising so strongly that a shortage was, at some point, “inevitable”.

Establishing new chip factories is difficult to do quickly, she adds: “It’s extremely expensive and requires a well-trained workforce.” It’s a potential spanner in the works for those who advocate “re-shoring” – relocating chip fabrication to a wider variety of countries, including those in the West, in order to ease the pressure on global supply chains.

Mr Chapman isn’t convinced that the market is up for grabs. He argues that Asia-based chip makers, such as those in Taiwan, China and South Korea, are already racing to meet demand, and will likely continue to dominate in the future.

Mr Köse says that consumers aren’t likely to notice price rises or widespread shortages of tech products this Christmas. Certain in-demand devices, such as games consoles, could become hard to get, with customers having to wait a few months for the item they want. However, he doesn’t expect interminable delays.

The bottom line is: the pandemic accelerated an already precarious situation for chip makers – we’re in the middle of a tech boom, supply can’t quite keep up – and it won’t get sorted out overnight.

It means that all sorts of people, including those seeking a new car like Mr Halpin, could continue to experience delays and disappointment for months to come.