Sustainability Corner with Ebenezer ASUMANG & Romein VAN STADEN)

“The Earth provides enough to satisfy every man’s needs but not every man’s greed.”

———–Mahatma Gandhi, social activist, lawyer, writer and politician

Are businesses acting consciously? Do they take responsibility for their actions? In today’s fast-paced business world, doing business consciously can be the key to success – yet how do you turn an organization into a conscious business? Although one seldomly hears the phrase “conscious business”, is it actually a thing? Honestly, the term sounds a bit pompous, painstakingly progressive, and far-fetched.

There is a progressive outlook on business that they will manage their overall impact on society, that they will aim to maximize the positive contributions and minimize the negative (Werther & Chandler, 2011). Business is embedded in society as its functional parts to serve the common interests, rather than dominate and hijack culture for their purposes and interests (Sun et al., 2010). In addition to identifying the range of social responsibilities and social problems facing the organization, a company must decide how it will address the issues arising from its liability (Banerjee, 2007). On balance, the last point suggests that businesses don’t have to lead the shift to a sustainable global economy. There are two alternatives. They can do more of the same, so today’s slow shuffle towards sustainability continues, two steps forward, one or more step back. Or they can delay the shift because of apparent advantages to them in the status quo (BSDC, 2017).

Becoming a conscious business lets us recognize that it is the key to tremendous business success (Kofman, 2006). Furthermore, Kofman (2006) states that a conscious business fosters personal fulfillment in the individuals, mutual respect in the community, and success in the organization. Conscious Business is the definitive resource for achieving what matters in the workplace and beyond (Kofman, 2006). As Kofman (2006) succulently puts it, a conscious business seeks to promote the intelligent pursuit of happiness in all its stakeholders.

Businesses need to be honest and transparent on their impact and report on what is right for their business. Moving the company to a sustainable growth model will be disruptive, with enormous risks and opportunities in danger. It will involve experimenting with new “circular” and more shrewd business models and digital platforms that can grow incrementally to shape new social and environmental value chains (BSDC, 2017). A company’s operations are increasingly conducted in “the social gaze” such that business activities and impacts are held in the entire limelight. Businesses playing a significant role in the route to sustainability (or unsustainability) is not in doubt (Banerjee, 2007). Whatever you want to call it, the conscious business must permeate through organizational values and constructive communications with employees, communities, and other stakeholders. In Good to Great, author Jim Collins shows how the most successful companies are the ones that thrive for more than financial success, as they’re motivated by higher values (Kofman, 2006).

A Fine Balancing Act

Businesses are the engines of society that drive us toward a better future (Werther and Chandler, 2011). Business, as part of society, is woven into its political and legal framework. Today, however, the meaning of a company signals a far higher degree of complexity (Werther and Chandler, 2011). The desire to “do well by doing good” motivates the world’s largest corporations collectively to direct billions of dollars towards a broad spectrum of social and environmental issues, whether through donations, volunteer programs, or other means (Pedersen, 2006).

Companies generate most of the jobs, wealth, and innovations that permit the larger society to prosper. They are the chief delivery system for food, housing, medicines, medical care, and other necessities of life (Werther and Chandler, 2011). According to the “Iron Law of Responsibility,” ‘society grants legitimacy and power to business and ultimately, the companies who do not use their faculty in a manner which society considers responsible will tend to lose it’ (Banerjee,2007, p. 20). It implies that businesses playing by the rules, which are required by society. Companies not only have to follow the law but act in a manner that will successfully compel the right kind of behavior. Although the statute is not sufficient, not in place, or not enforced, that good behavior to the employees, the suppliers, the consumers, the physical environment, and the community to the world should be an essential and core responsibility to the community of businesses.

According to Blowfield and Murray (2019), increasing attention is being paid to the idea of business as a solution to poverty. That is not a paraphrase of the centrality of business to the capitalist economy as the source of employment, goods and services, and wealth. Instead, it is the belief that a company can consciously invest in ways that are simultaneously commercially viable and beneficial to the poor. One of the constants of business’s interest in its relationship with broader society this century has been its concern with climate change, which in many ways exemplifies the business-sustainable development interaction (Blowfield and Murray, 2019). The populace also knows that climate change will affect some of society’s most fundamental principles and institutions (Blowfield and Murray, 2019, p.60).

We anticipate much higher pressure on business to prove itself a responsible social actor, creating good, adequately paid jobs in its supply chains and its factories and offices (BSDC, 2017). It’s also an acknowledgment that the strain between business and society will continue as each tussle with the changes ahead brought on by disruptive advances in technologies like artificial intelligence and robotics (BSDC, 2017).

At last

One has to be intrigued less by the phrase “conscious business”, but by the sentiment.

“Business as usual” will not realize any market transformation. Neither will disruptive innovation by a few sustainable pioneers be enough to drive the shift: the whole business sector has to move (BSDC, 2017). But, all in all, when we successfully create an organization filled with self-awareness employees who are value-aligned, we go beyond “business as usual” to start a truly conscious business.

References

Werther, William B; and Chandler David (2011): Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility: Stakeholders in a Global Environment. 2nd Edition., SAGE Publications, Inc, California.

Business and Sustainable Development Commission (BSDC) (2017): Better Business, Better World: Executive Summary. The report of the Business & Sustainable Development Commission, London. Available from: http://report.businesscommission.org/uploads/Executive-Summary.pdf [Accessed 05 June 2021].

Banerjee, Subhabrata Bobby (2007): Corporate Social Responsibility: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. Edward Elgar Publishing Limited, Cheltenham, UK / Northampton, MA, USA.

Sun, William; Stewart, Jim; and Pollard, David (2010): Reframing Corporate Social Responsibility: Lessons from the Global Financial Crisis. Critical Studies on Corporate Responsibility, Governance, and Sustainability, Volume 1, Emerald Group Publishing Limited, United Kingdom.

Blowfield, Michael. & Murray, Alan (2019): Corporate Social Responsibility, Fourth Edition. Oxford Univerisity Press, New York.

Kofman, Fred (2006): Conscious Business: How to build value through values. Sounds True, Inc, Boulder, USA.

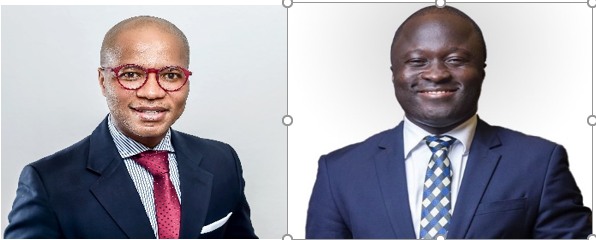

About the Writers:

Romein is a (self-confessed) Pan-Africanist by heart. His diversified professional career spans many different sectors, i.e., local government, mining, consultancy, construction, advertising, and development cooperations. He has an MBA in CSR and various qualifications in engineering, environmental health, and leadership. Romein is the Head: Business for Development at PIRON Global Development, Germany (www.piron.global). Contact him via ([email protected])

Ebenezer ASUMANG is a Development Communication Specialist, an SDG Market Building, SME & Finance Researcher, serving as Senior Project Manager with PIRON Global Development, Ghana (www.piron.global). Contact him via ([email protected])