…the urgent need for an uncommon sense approach

The results of Ghana’s Covid -19 economic stress test is finally in. The economic crisis we are experiencing, as a result of lockdowns and other policies to control the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, provide real objective metrics regarding the level of resilience of Ghana’s economy. No more subjective political hype because this crisis is truly global and unprecedented.

We now have solid empirical data from which to draw reliable insights. Clearly, in spite of huge budgets and accrued debts, implementation of the MDGs, SDGs and other developmental programs over the past 64 years our preferred strategies have failed to resolve our most pressing socio-economic problems in a sustainable manner. The results of our political and socio-economic decisions, our way of life, are now laid bare for all to see. The state of Ghana’s real economy, which escaped scrutiny during the 2008 international financial crash because of our relatively weak integration into the world financial system, now stands disrobed so to speak.

The brutally frank results of the recently published GSS Multidimensional Poverty survey makes nonsense of claims by the international governance and financial institutions regarding the effects of their advice and support. The vulnerability and helplessness of large sections (up to 21.4% severely poor according to the Ghana Statistical Service) of our society during this crisis confirms our poverty eradication claims are highly debatable.

According to GSS’s recently released Multidimensional Poverty Report 46% of the population is poor. In practice, large sections of our people have no savings and live from daily wage to daily wage with no safety net. Real issues of systemic poverty, unemployment and low access to basic amenities and essential services exist and need to be tackled with all seriousness. Our low production and consumption capabilities of essentially strategic goods and services result in low job creation opportunities and national reserves levels are woefully inadequate for mitigating the effects of the pandemic (about GHS 12 billion unplanned expenditure) without external support or putting further tax pressure on the Ghanaian people.

The structure and content of past and contemporary local and international relationships or arrangements on both the economic and political fronts have failed to produce a level of self-reliance necessary for the development of our desired level of economic resilience. As the strategist Prof Rumelt suggests deep tectonic chain-linked faults in the structure and workings of Ghana’s economy have been exposed by the COVID-19 pandemic. We have to fix all integrated (linked) core economic problems.

These problems existed well before the pandemic but were covered up by our governments because politicians either did not appreciate the problems or simply kept ‘kicking the can (problems) down the road’ to the next government. According to Dr. Thomas Sowell, “that is the truth (whether palatable or unpalatable) about where we are now that we must first acknowledge as we develop social and economic strategy for advancement and progress towards our destination” of a resilient economy of Ghana.

Quite an impressive number of recent Covid-19 inspired publications have documented firm, sector and country level research findings, analysis and opinion papers on the effects of the pandemic.

Generally, scholars and practitioners have focused on providing solutions for severely disrupted demand and supply chains, problems with employee retention, unemployment, lost foreign direct investment, drastically reduced international trade, lost government revenue and social intervention issues etc.

The main theme of these publications has been how to survive or minimize the effects of the pandemic and quickly restore organizations to their original levels of operation and status quo. Essentially, they are asking us to re-create our old society and maintain our old culture. This is, in my humble ‘street’ opinion, the popular traditional common sense approach to resolving this conundrum.

To paraphrase Professor Jordan Peterson, they are answering the question “what has been destroyed?” which I agree is the wrong question even if it is the easier question to answer. Naturally, those benefitting from the current structure and arrangements as well as those who anticipate that they will soon ‘have their turn’ at exploiting the system, or those looking for quick fix short term solutions will advocate for non-consequential, minimal or band aid reforms only.

The writer, on the other hand, belongs to the school of thought which argues that it would be naïve and even foolish to limit remedial action to restoration of the pre-COVID-19 status quo which has left large sections of our population in poverty in a non-resilient economy.

The correct questions to ask are first “what remained standing during the lockdown” (Jordan Peterson, 12 Rules for Life, p37)? What aspects of the Ghana economy remain standing during, or will remain standing after, this pandemic? What is our real time strategic fallback position?

And secondly, how can we significantly and rapidly improve our fallback position so that we increase our chances of surviving any crises with minimal collateral damage. This will require some uncommon sense solutions which challenge our current way of life and its underpinning philosophies.

By uncommon sense solutions I refer to contrarian strategic solutions, as advocated by Professors Goddard & Eccles, based on specific perspectives and insights unique to our Ghanaian context which only Ghanaians who feel the heat can decipher. Adopting common sense or conservative and generic strategies which have worked for our competitors (and detractors?) under different contexts cannot lead to unique or sustained economic breakthroughs for us.

We cannot resolve our challenges or beat the market by continuing to apply the linear common sense, ‘one solution fits all’, proposals being promoted by the multilateral financial institutions for the development of third world countries. These common sense neo-liberal economic solutions (theory) which favor rich multinational organizations, with access to large capital, have failed countries like Ghana and resulted in the marginalization of our continent.

Clearly, the common sense logic and arguments advanced in support of global trade has failed us woefully because the market is imperfect and skewed against us. A situation that is made more complex by our own internal weaknesses. We need new (radical?) and different economic perspectives, ideas and beliefs if we are going to beat the competition in this global village.

As Banerjee and Duflo note China, Vietnam and Bangladesh etc still have large reserves of poor people prepared to work for abysmally low minimum wages. Even more important, according to leading investors who locate production facilities in China and Asia in general, is the fact that they have a deep, sustainable pool of highly skilled workers and advanced tooling in one location.

These countries also constitute large markets which are attractive to manufacturers. A competition strategy anchored on the traditional paradigm of regular and cheap manufactured goods is therefore bound to fail even in the near long term. We need to determine a new set of priorities by using processes underpinned by arguments, logic and assumptions which reflect both our current realities as depicted by empirical analysis of data and our aspirations.

Ghana needs to be bold and courageous even as we experiment with new long term strategies which challenge conventional economic or political wisdom and leverages our unique insights. We need an aggressive injection of local entrepreneurial effort in these remaining sectors. By local entrepreneurs I mean private individuals, the central government, regional and district administrations, cities and towns as well as assemblies which should be empowered, legally and financially, to set up and own privately managed (via agency) enterprises in the surviving protected sectors.

Of course, to paraphrase Osagyefo Dr. Kwame Nkrumah (Africa Must Unite), we will stumble and fall along the way because it is an unchartered course and also because of stiff opposition but we will learn from our mistakes even as we adapt and adjust our policies and activities on the ground to make the strategy successful.

This is normal. After all, we also know what has not worked for 64 years. What is important is our commitment and dedication as we innovatively implement tactics and necessary disciplined behavior dictated by our new integrated strategy.

This article suggests that the components of Ghana’s real economy which remained standing during and after the lockdown constitutes our arsenal against the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and indeed, against any future crises from different sources.

Our uncommon sense strategies for building a resilient economy should be anchored on these surviving sectors that should be developed to produce core industrial value and profits.

Yes, they may be weak and inefficient today but they remained standing and relevant during the crises nevertheless. An in depth study of the economic development strategy of China will provide some significant and valuable insights regarding the way forward.

We urgently need a different logic for strategy development and efficient resource allocation to these sectors that we have identified as vital and central to our existence as a people. This is the key factor that should guide our new strategy for rapid and resilient economic development in the post COVID-19 era.

We must think local (in terms of well managed market participation, competition and regulation) and simultaneously act strategically regionally, continentally and globally (ie LORECOGLO) to maximize output from identified opportunities. This is a contraindicative and uncommon sense position as we prioritize the basic structural transformation of selected sectors of our economy and tap into external factors like the AfCFTA which accelerate our local agenda.

The apolitical state of affairs of some major remaining sectors:

What remains of our health sector are underperforming and generally un-innovative hospitals as well as traditional medicine and scientific research institutions which although staffed with brilliant professionals are under equipped, under resourced and poorly managed. Our residual manufacturing sector, is weak with generally questionable production standards and low levels of local raw materials utilization.

This includes our local pharmaceutical manufacturing enterprises producing critical indigenous products often rejected by our own regulators even during this pandemic. We still do not produce (and cannot design) our own machine tools or acquire skills necessary for the development of a vibrant and competitive manufacturing sector.

All this in spite of on-going attempts by the Business Resource Centers (BRC) of the Ministry of Trade and Industries to decentralize and facilitate local manufacturing.

After the closure of 35.7% of established enterprises during the partial lockdown with 16% remaining closed after lockdown was eased (GSS Business Tracker Survey, 2020) Ghana’s private sector is now dominated by stunted MSMEs, with weak balance sheets, which dare not attempt risky innovations.

They have brittle organizational backbones and immediately begin to regurgitate employees under minimum stress. The so called large investors we expect to transform our economy are jumping ship. Worse, although they are identified as the engine of economic growth, the indigenous private sector receives inadequate long term support and are left to the vagaries of international competition.

On the public and civil service front we are left with a bureaucracy which does not, and cannot, serve the public interest because it lacks effective checks and balances necessary to address non or poor performance and conflict of interest situations.

The powerful and self-serving workers’ unions do not make life any easier even though a large and disproportionate amount of state revenue goes to paying salaries of government workers. Kwame Nkrumah used the metaphor of a nail without a head lodged in a piece of wood to express similar frustrations.

This is aggravated by a legal and justice delivery system which in practice still de-emphasizes justice, access, truth, speed and targeted operational costs reduction for both the clients, practitioners and the legal system in general.

In a society such as ours, with a dearth of trust and trustworthiness, this weak legal environment has dire consequences for commerce and economic performance. Complaints regarding the non-enforcement of laws on our books continue to fall on deaf ears.

Politically, we are saddled with a stomach-directed and partisan local media which has abandoned truth and its watchdog role.

They are suffering a terrible hangover from the onslaught by social media which is making mainstream media irrelevant. In their desperate search for attention today’s media people will even engage in investigative reporting with no respect for hard earned reputations. Even worse, nothing is sacred for our power seeking political players (the bed fellows of the media) and parties.

Not even ethnic and tribal sentiments nor the unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic is spared diabolical political machinations. Likewise, our youth and pre-tertiary schools are fair game and have been sacrificed on the political altar.

The cost of political campaigns is probably at the lowest level ever experienced in Ghana as large rallies have been banned and political parties have to find more innovative and less costly ways to engage the electorate.

After almost 30 years of the fourth republic, we are yet to find even minimal consensus or common ground regarding our path to national development between the major parties.

Agriculture, the mainstay of our economy, generally proved resilient on the food supply front during the pandemic. Apart from the initial food price hikes, induced by panic buying, the market stabilized and we did not experience shortages in the supply of staples.

The ‘Planting for food, crops and jobs’ programs seem to be making significant impact. Our emphasis on export crops instead of local food production and raw materials for local industry however, means we continue to sacrifice resources badly needed for food security for foreign exchange generating activities which were very sensitive to the global lockdown and reduced international trade resulting from the pandemic. We are still basically consumers of what we do not produce.

In spite of gradually increasing modernization of this sector, agriculture generally still remains unattractive to our youth because relative to other vocations it is financially risky (land acquisition problems, largely rain fed with high post-harvest losses and unstable prices), hard, back-breaking and unrewarding work. Irrigation infrastructure is still woefully inadequate and is reported to be less than ten percent of the required capacity.

Our remaining banking sector is weak because of extremely low savings by a population with high unemployment and underemployment components resulting in our generally low earning power. Our banks, both foreign and indigenous, and other financial institutions are totally insensitive to local economic and developmental needs.

They are only primed to exact their maximum ‘pound of flesh (profits)’ from the system.

This situation is exacerbated by the existence of an impotent central bank which cannot influence the price of credit even for government owned banks, is not proactive when it comes to regulation and may even be managed by some personnel complicit in financial crimes by banking cartels.

As usual, the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) of the Central Bank continues to hide behind funny economic jargon to escape scrutiny of their decisions. Only during this COVID-19 era have the banks finally reduced interest rates because of high default rates and low demand for loans.

The central bank has also reduced commercial bank cash reserve requirements in a bid to free up funds as the real economy shrinks. Additionally, our inability to intervene in the foreign exchange market to mitigate the effect of capital flight and reduced foreign exchange receipts means the Ghana Cedi has found its real level against convertible currencies.

Ghana’s telecommunications sector is also left with dominant IT and telecom organizations, fully controlled by foreign interests, which take full advantage of poor regulation to exploit its addicted, locked-in and hooked customers. In spite of their huge profit margins the telecom organizations continue to provide poor service and coverage even as they expand their market offerings to include financial services.

Their prices remain unchanged despite highly increased consumption of data, voice and associated financial products during this COVID era. In this age of comprehensive internet usage and heightened need for cyber security we are left at the mercy of these foreign monopoly organizations that only pay lip service to Ghana’s developmental issues.

Similarly, our mining sector remains unchanged the past 40 years. It is still dominated by foreign investors and organizations which demonstrate no interest in impacting their host communities in a sustainable manner despite benefiting from an unprecedentedly high gold price and a ridiculously conducive investment policy. We still have no operational solution to the small and unlicensed (galamsey) mining menace.

Our local records of gold exports are far outstripped by import-from-Ghana records of recipient countries like India and China. Meanwhile, the production of portable water and energy in Ghana remains inefficient under both public and private controlled organizations. Production losses of up to 50% of output as well as ridiculous production and distribution agreements ensure that Ghana’s manufacturers continue to pay high prices for utilities which make them uncompetitive locally and on the international market.

Socially, we have achieved some remarkable feats. COVID-19 has put child education and upbringing firmly back where it belongs…..in the bosom of parents. Both child and parent are stuck at home and parents have greater responsibility for supervising learning and playing activities of their children. Our adherence to personal hygiene protocols have impressively reached unprecedented levels. Due to mandated hand washing and cleaning with sanitizers as well as wearing of face masks there is a reported reduction in the incidence of common diseases like cholera, dysentery and typhoid etc which plagued our communities.

Regarding funerals, weddings, parties and other social gatherings we have finally managed to force down expenditure on such activities by enforcing emergency social distancing and participation rules. Unfortunately, the need for enforcement of lockdown instructions during this COVID-19 era confirmed that the psyche of our private and public security organizations is clearly still stuck in the brutal 1979 coup era. They still do not hesitate to use control methods made popular by the forces of the erstwhile apartheid South Africa.

Our Ministry of Finance (MOF) which is responsible for fiscal management of the economy has suffered a rude shock as its sources of revenue have been severely hit by the COVID-19 pandemic. Government reports a shortfall of about GHS14billion in 2020. These include oil revenue shortfalls due to the combination of reduced production and a drop in world prices, over 40% cargo throughput drop in the shipping and maritime industry during the early part of 2020 only to be rescued by the transshipment activity of Meridian Port Services (MPS).

Export trade volume also experienced a drop of up to 60% and hemorrhaging or collapsed enterprises meant the loss of tax revenue. The ministry however still implements a rigid and high tax regime that is not designed to stimulate local wealth creation or growth. Indeed, in a self defeating move, the Ghana Ministry of Finance even charges VAT on NHIL & Get Fund fees (as if these are value creating or adding) thereby further impoverishing local enterprises. Despite strong empirical research evidence to the contrary, Ghana still focuses on Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and prostitute world-roaming surplus funds as our preferred vehicle for transformation of our economy.

These foreign investors do not spend their huge profits within the Ghana economy and as such create very little additional demand for locally produced goods and services. With the advent of COVID-19 FDI inflow into new businesses and sectors dropped as expected within the first two quarters and surprisingly recovered to over $2,600 million.

Our economy is still controlled by unrelenting global financial institutions that continue to sell us economic experiments which have no possibility of solving our complex problems whilst securing super favorable investment terms for their conglomerates.

Generally, Ghana is still a severely import oriented consumer nation with a sustained negative balance of trade. And (my personal beef) the MOF is still running the SSNIT Ponzi scheme which ‘steals’ worker’s incomes and provides ridiculous pensions upon their retirement.

On the sanitation front what is remaining of Ghana’s sewerage and garbage management infrastructure and services is inadequate given our production levels, types and dispersion of waste.

Our current installed capacity of modern sewerage treatment plants, engineered garbage dumpsites, un-engineered open pits, land fills and collection arrangements leave this environmental menace unresolved.

Our inadequate network of drains (covered or open and choked) which trails community development, continued open defecation and unenlightened individual waste disposal activities coupled with our weak enforcement of sanitation laws leaves our population at the mercy of disease, erosion and a relatively high contribution to green house gas emission.

Education in Ghana has been severely paralyzed by the COVID -19 crises and our corollary need for social distancing. Although children of upper and middle class parents in private schools benefit from virtual classes, the broad masses cannot afford laptops or internet access because of high internet data usage requirements and high prices.

Our National Service Scheme still has practically no emphasis on patriotism or a graduate’s sacred duty to contribute meaningfully to national development. Parents and students alike use the scheme to position wards in perceived successful organizations in order to improve their chances of securing lucrative jobs and personal development opportunities. Industry personnel requirements and output quality of the educational system are still poorly aligned. Even worse, the moral fabric of our society is in serious disarray. This was manifested by the level of indiscipline exhibited by our students during recent WASSCE examinations.

As a result of the need for social distancing in examination halls because of COVID-19 students had a zero chance of cheating or illegal collaboration.

To my utter amazement students rioted and used videos uploaded on social media to shamelessly and openly lambast and threaten political and educational authorities for daring to organize such a tightly invigilated event.

Research at the tertiary level still remains on dusty shelves with no attempt to commercialize findings or make them easily available to interested parties.

Also remaining are new digital shopping platforms and new logistics arrangements for products and service delivery, our deteriorating road networks and woefully inadequate functional pre-colonial rail lines with new projects still in the works and last but not the least, a large, aggressive and highly opinionated army of illiterate and semi-illiterate indigenes impervious to scientific knowledge or information.

It is also instructive to note the range of redundant and unessential expensive infrastructure, services, products and relationships of no strategic value for our survival and way of life during this COVID-19 pandemic.

These include the numerous hotels, music or entertainment enterprises and joints, commercialized sports facilities, restaurants, office edifices, political rallies, religious edifices, commercial aviation, local and international tourism facilities and arrangements, irrelevant traditional educational infrastructure, unnecessary elaborate cultural practices, superfluous downstream and upstream oil and gas installations, deserted recreational centers and play grounds, theaters, non-food retail shops, barbers shops and hairdressing salons etc.

With this clear picture of our state of affairs Ghana has a rare opportunity to recalibrate, restructure and recreate our economy using a new and more sustainable strategic framework.

Although a comprehensive catalogue of uncommon sense solutions for all remaining sectors is beyond the scope of this article I suggest some general principles and a few specific examples which will demonstrate the urgently needed uncommon sense paradigm shift in our approach to building a highly resilient economy.

Proposed Solutions:

First, instead of wasting precious time and resources trying to achieve limited and diversionary goals set by our so called ‘international collaborators’ Ghana should implement a smart and innovative long term strategy which enables us focus our scarce resources on shoring up the critical surviving components of our economy.

Some of these ideas may be old and others may highlight totally new ways of approaching this daunting problem. Ideally, programs like the COVID-19 Alleviation and Revitalization Enterprises Support (CARES) program should be limited to, and aim at stimulating only, those sectors which remained crucial to our survival during the crises. In practice we may have to continue allocating some minimal resources to maintaining activities in some less crucial sectors during our transition to the new structure.

What is important however, is that we clearly appreciate the fact that we cannot mortgage our right to independent macro and micro decision making in these remaining sectors.

We will have to develop new and different strategies for quickly industrializing and growing these crises-resistant sectors organically if necessary after properly evaluating and ranking them. We need tons of humility which dictates functional ability and modular installations instead of unnecessary competition with the Joneses ie advanced economies.

This is indeed an urgent security matter which must be addressed even as you read this article. The sectors which collapsed, on the other hand, should be opened up to interested ‘prostitute’, expensive and unreliable FDI so they bear the higher business risks.

A well regulated market will take care of the FDI business and ensure that it works to our benefit. But that is a discussion beyond the scope of this article. Ghana must develop a superior level of self-reliance in these pandemic resistant sectors of the economy.

Even more importantly, we must clearly define and establish our own concepts and perspectives of progress, development, growth, poverty, security, democracy and education etc. and develop our own metrics for measuring them.

These will guide our future decisions and plans. So far, the so called universal indicators and measurements of development and growth have only served to divert our focus from wealth creation resulting in our marginalization in a globalized game with rules outside our scope of influence or control.

For example in our new Ghana, the degree (ie speed and quality) of integration of the different facets of our economy, how versatile our production facilities are, the degree of diversification and self-reliance of the economy, the alignment of output of our educational institutions to industry requirements, conflict of interest and corruption in public service, and even the level of participation of the general populace in determination and protection of the national agenda will be the indicators used for the meaningful assessment of national progress. Metrics regarding our level of integration into the global economy will be de-emphasized.

The direction of growth and development instead of how fast we develop will be emphasized. I am aware there will be serious resistance, attacks and even sabotage by sceptics, vested interests and their local collaborators who will lose their choke-hold on Ghana’s economy. These proposals will be classified as idealistic, naïve and unachievable.

We however, must stand our ground and assure them that a strong and resilient Ghana will be a better and reliable partner in mutually beneficial relationships even as we pursue our agenda with absolute conviction and dedication. Although subsequent articles will focus on specific solutions for identified remaining sectors this article provides two practical examples of uncommon sense solutions.

Example 1 of uncommon sense solutions:

I first draw attention to the most important factor in our strategy landscape. This is the group of people, primarily Ghanaians, who were locked down in this country and in the diaspora as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic with nowhere to go. Ghana today is inhabited largely by a group of cynical and disillusioned individuals who seem to have reached the conclusion that Ghana is not worth dying for. We are an emotionally distraught and broken hearted people who feel deceived and exploited by our leaders. We have no concept of a ‘Ghanaian economic dream’.

As far as the majority of us are concerned the only way to attain some measure of personal success and growth is to pursue an individualized and selfish agenda. We are generally indifferent to the plight and suffering of our compatriots. We will use all and any means or forms of ‘entrepreneurship’ and ‘intrapreneurship’ to achieve our personal agenda whilst sacrificing our nation, communities and fellow nationals. There is a dearth of trust and trustworthiness. Political, business, religious, gender / child and even philanthropy entrepreneurs now consider their ‘ventures’ as legitimate means for self-aggrandizement. Opportunism is the number one virtue. Legitimacy is now defined only quantitatively as ‘being rich’. The end justifies the means.

This is our reality and we have made sure our children (generations millennium, Z and alpha) understand this. We have made sure today’s entitled millennial generation, our future leaders, have one agenda and one agenda only. To reach the pinnacle as fast as possible with as little effort or sacrifice as possible irrespective of collateral damage caused en route to achieving their goals. Advanced technology, increased globalization, increasingly widespread democracy and transparent governance, mass education, mass communication, increased access to information and expanded inclusiveness etc which were originally conceptualized as a means for rapid social development are all now just tools which allow the millennium generation to pursue their singular self-interests at minimum cost.

The core thesis of this article is that this immature and unbalanced approach to self preservation is a recipe for chaos and stunted economic growth. How do we change this national psyche and motivate our youth to citizenship, higher levels of patriotism and belief in Ghana? How do we impregnate our collective national subconscious mind with fearless pride in a new and unique Ghanaian heritage?

My proposed uncommon sense integrated solution to remedy this particular complex problem is predicated on three mutually reinforcing pillars. First, the development and implementation of a tough and effective public management systems. Second, mutually beneficial collaboration with Ghana’s faith based organizations (FBOs) and thirdly, an enhanced practical pre-tertiary school curriculum.

Clearly, changing ingrained individual or group mindset and behavior is a tough, arduous and long term endeavor for any country. A shorter and more effective route will be to establish effective and objective (and democratic) public management systems. Since we cannot trust our citizens at all levels to ‘do the right thing’ voluntarily we must coerce them by making the price for errant and deviant behavior exceptionally high and unattractive. We must have the physical and legal frameworks to underpin and implement this.

The recently passed Criminal Offenses Amendment Bill and the Right to Information law are steps in the right direction but must be tightened further. Clearly defined corrupt and inappropriate behavior should be made truly expensive options for officers in responsible positions (in both public and private organizations or institutions). According to Banerjee and Duflo, China in an effort to save the reputation of its industries ensured that violators of their laws suffered “devastating consequences”. Ghana must aggressively adopt a similar stance for all our sectors. Generally, crime must lose its glamour because we actively and unrelentingly pursue perpetrators in the fashion of Nazi hunters. Our laws must capture and reflect the moral, work, environmental and sanitation standards we determine are necessary to promote responsible citizenship. Ghana’s definition of, and position on nepotism, conflict of interest in the public space and socially acceptable behavior should be clear and unambiguous. The current programs for the digitization of national identification of all individual and corporate citizens as well as operational subsystems should be accelerated, broadened and deepened to ensure effective monitoring of all major socio-economic activities.

It is even more crucial that our rules and laws should be firmly applied without fear or favor. Justice should be swift and fair no matter whose ox is gored. Good and operationally successful examples in other jurisdictions are the implementation of the income tax filing laws / system in the USA and the system for controlling environmentally responsible behavior in Singapore.

On the flip side, as successfully implemented by Singapore, Ghana must attract the very best quality personnel into these crises-surviving sectors. Indeed, Ghana’s politics, the civil and public service and the executive apart from being right–sized must recruit a core of the most brilliant and patriotic individuals / professionals, train and protect them and provide them really befitting performance–related remuneration. No pretending to pay them!! The smart private sector will take the cue and follow suit. Our new economy must, and will, be built on a reliable meritocracy.

Although there are multitude problems with the impact of faith based organizations (FBO) in Ghana, they actively compliment government’s health delivery, education, peace building and some social intervention efforts. They however, do not directly or specifically call their congregations to nation building. Indeed, the importance of self-sacrifice, a conscientious approach to secular work and instructions for an honest day’s work have been relegated to the back burner or completely ignored by faith based organizations. Given their structure, inherent and inordinate control over the psyche and behavior of their members this article, shares the views of Dr. Henrik Clarke and, posits that should the government directly and honestly elicit the support of faith based organizations for a clear and well articulated national economic liberation agenda they will, and can, assist establish and ingrain desired work ethics, virtues and morals which will help change the behavior of the Ghanaian worker in favor of nation building.

The FBOs should be encouraged to establish commercial ventures which will serve as training grounds for their members and allow them to contribute directly to economic growth. As a people our culture and character are firmly anchored on our religious beliefs. Therefore, the uncompromising emphasis by our religious leaders on the love of God and country, abhorrence of all forms of corruption and laziness, demand for righteous work, promotion of frugal living and acceptance of contributions from honestly earned income, even as they pursue their religious objectives, will positively impact our society. This, I think, is at the core of the American economic model.

The third component is the inclusion of an actionable practical component in pre-tertiary education curriculum that targets and promotes a culture which emphasizes what Thomas Sowell calls “economically meaningful skills”, love of community, practical problem solving and patriotism. Paraphrasing Thomas Sowell again “…the education of our youth must benefit society at large from their work later in life as high powered intellectuals”. Students should be exposed to examples of selfless leadership and involved in seeking practical solutions to problems or challenges within their communities. For example, problems with water conservation, post harvest loses, personal hygiene, environmental issues and the effects of corruption on poverty and economic development should be introduced early at school. The need for honest work, the wisdom in frugal living and a collaborative approach to problem solving, innovation, the joy in identifying and developing solutions for the big challenges society faces etc should be inculcated in our youth from a very early age. It is crucial that our future leaders be taught our culture, our history and Africa’s true contribution to world civilization.

The curriculum must emphasize the need for Africa to regain its rightful place and respect in the community of nations as the original source of world civilization. Through the use of dedicated social media / information platforms, story telling, excursions to project sites and enterprises within their communities, practical experiments and discussions of contemporary news items we can create an army of smart and passionately engaged youth.

The capacity of our youth to learn about, and understand, all issues should not be underestimated. Yes, filling the bellies of our students is important but even more crucial and urgent is the need to fill their minds with the right thoughts and attitudes. It is the only way for us to transform the character of leadership in government, business and society in general.

The sophisticated, genuine and non-opportunistic integration of these three components constitutes an uncommon sense long term solution to remedying Ghanaian individualistic behavior and the lack of patriotism.

The specific configuration of these three components we choose will constitute an integrated solution for a complex challenge because an uncompromising public management system will ensure smart and efficient allocation of our resources which in turn ensures that our educational system receives adequate funds for the aggressive implementation of our new curricula.

The schools in turn feed industry and society in general with well educated and balanced youth adequately prepared for public and private service even as the faith based organizations help build a culture which highlights love of God and country. These three components are mutually reinforcing and the circle spirals upwards all the while self correcting and adjusting our assumptions and belief systems for missteps, emerging opportunities and set backs till we create the kind of society we desire for Ghana.

Example 2:

The second example focuses on our large, multi-faceted and complex health sector which is directly engaged on the frontline in the fight against the Covid-19 pandemic. The proposed uncommon sense health sector strategy will comprise at least three core components which may not be easily expressed or modeled as the proposed solution may require integration with solutions for other sectors like agriculture (nutrition), sanitation (disease prevention) and education (lifestyle).

The first component is a paradigm shift to a tremendously increased allocation of resources to the development and implementation of policies for disease prevention, public health education and health information dissemination.

The second component is the establishment of a smaller but highly efficient and responsive, research oriented remedial health delivery service whilst the third component is a fully functional integrated manufacturing and industrial complex or ecosystem anchored on the first two components.

A significant portion of the Ghanaian populace, from inner city slum dwellers, workers and public transport providers across the country etc right up to our politicians and government, demonstrated clearly that medical science and its dictates ranks rather low on our hierarchy of priorities. Official government policy during and after lockdown mandating social distancing, wearing of masks and hand washing was blatantly ignored and even ridiculed by a large majority of our population including political leaders. Some of whom paid the ultimate price with the loss of their lives. A closer look at this phenomenon strongly suggests that it is pervasive and reflects a culture that has generally low appreciation of scientific insights and core technology.

Yes, we appreciate and use applied technology as we drive latest design vehicles fully loaded with accessories, use new design mobile phones, watch curvilinear television sets, use new medical diagnostic gadgets when we are sick, construct complex bridges etc but as a people we don’t understand or appreciate the power of the underlying technology or science and innovation regarding winning in the global market place.

It is not a top priority for us. As a proxy for measuring our commitment, as a nation, to development of core advanced scientific knowledge we should check our budget allocation for research and track private funding and bank support for new technological research over the past 20 years. I do not have the data but anecdotal reports indicate that this is practically non-existent.

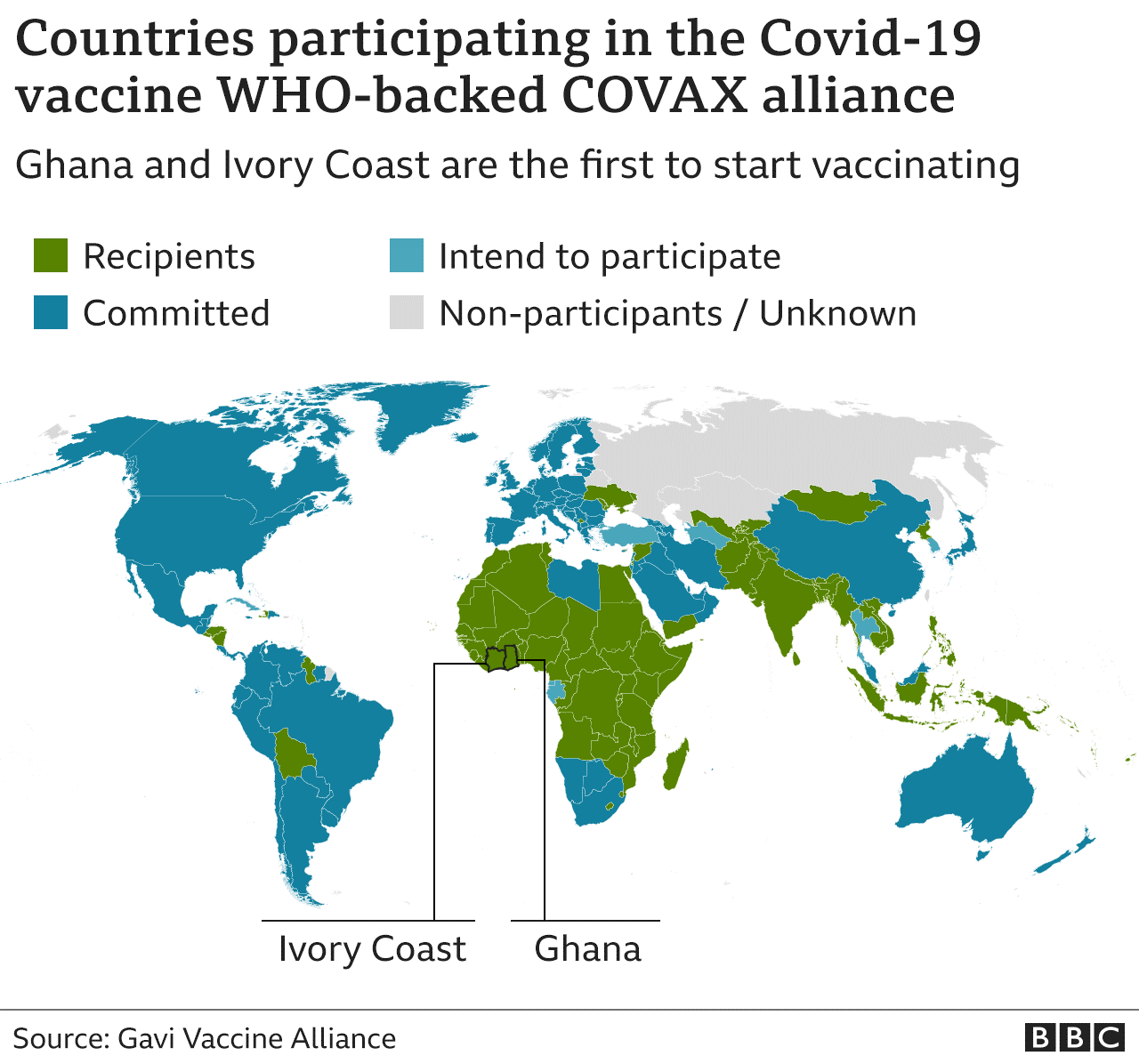

For example, during this pandemic our hard working scientists and technicians at the Negouchi Research Institute, carried out tests to identify infected patients. However, all test kits (both standard and rapid) including sample collection apparatus used were imported. We have no programs to develop our own test kits for covid-19 or any other disease for that matter. We continue to rely on technology developed by other foreign institutions for even malaria test kits. We have neither the requisite human capital nor technical knowhow for developing or producing sustainable innovative solutions in this sector thus limiting its ability to contribute to Ghana’s Gross National Product (GNP). The conditions simply do not exist. The question of our very own vaccine development program and production in Ghana has been off the table at all levels.

Merck Life Science GmbH acknowledges this vaccine gap exists and moved to set up a facility (just packaging or real production?) in Accra in 2017 to take advantage of Ghana and the anticipated AfCFTA. After all, it is estimated that over 90% of vaccines produced by Merck are imported into Africa. It might interest you to know that Merck GmbH is big and rich today because over the past 100 years, with the support of their government, they invested in core technology research for pharmaceuticals, vaccines and also for crystals (originally from carrots) used for manufacture of digital display equipment like colored TV sets and watches etc. They own many patents for these specific core technologies. China recognized the power of core technological knowledge and has been quietly acquiring leading technology companies in Europe and America in order to secure knowhow and patents among other ‘tricks’. Following a radical paradigm shift in our understanding and appreciation of science successive governments should implement a well funded, accelerated and targeted program locally which includes sending students abroad for relevant advanced studies in specific critical core sciences and technology development processes. We must continue Nkrumah’s manpower development program with necessary adjustments.

Secondly, we should monitor the worldwide technology landscape, locate and tap the experience of local and diaspora African inventors, scientists and top medical business executives with the view to combining them into formidable teams the same way we chase footballers all over the globe for the national team. We need a very high level of sophistication and intensity if we are to succeed with this new paradigm to change the focus of our research institutions towards innovation on which to base industrialization of the sector.

These teams should assist set up and grow government-supported laboratories and related startups utilizing next generation technologies in specially designated enclaves. Simultaneously, government must actively work to attract world renowned medical R & D organizations and scientists to Ghana through special incentives or encourage collaboration with local institutions and development agents. Although we do not have the market size to absorb large-scale production we must own the technology and processes used by large-scale producers and leverage this as equity.

By supporting local entrepreneurs (including central government, regional administrations, constituencies and assemblies working via agency) to invest in leading advanced offshore medical technology companies Ghana will keep pace with developments and standards world wide.

The second pillar of the uncommon sense health sector solution addresses the need for a change in the focus of our health policy and implementing agencies / institutions programs from a highly disease curative orientation to a more disease prevention orientation even as we work to significantly to improve operational efficiency at various levels of healthcare delivery and training. This is premised on the well-known fact that a strong and effective community / public health regime supported by health promoting life styles significantly reduces out patient pressure on hospitals and clinics at all levels. The specific health budget ratios and resource allocation by ministries and implementing agencies should clearly reflect this change in strategy.

We must listen to and engage people like Pro.f Akosa seriously. The aggressive personal and public hygiene education drive which was successfully implemented during the early stages of the covid-19 pandemic should be broadened to include health and safety initiatives all levels of public interaction, intensified, institutionalized and backed by the necessary laws.

This will be integrated with the activities and programs of the Ministry of Education, which will redouble its effort regarding personal hygiene education in schools, and the Ministry of Water and Sanitation responsible for waste management and availability of portable water. This second pillar of the public health dimension is targeted at generally boosting individual immunity status.

The third pillar of the health sector uncommon sense solution seeks to vastly and radically improve productivity and efficiency at both the level of individual personnel and the institutions as a whole respectively.

Whilst general sources of mismanagement ie bad / poor planning, monitoring, personnel management, resource allocation and finance etc of organizations within the health sector is well known, what is really killing our health sector is the huge self serving underground (black market) economy for medical services and goods which exists in government health institutions and organizations. Research generally shows that there is a strong inverse relationship (negative correlation) between growth of an entity and its underground economy. Specifically, the larger the underground economy we anticipate a lower performance and growth of the focal organization. Our uncommon sense solution will aggressively work to progressively eradicate and criminalize this canker. Only when we eliminate this negative sub-culture can we bring these organizations to their right efficient sizes and structure, eliminate waste of resources and fully utilize employed personnel. The underground economy within Ghana’s health sector exists at three major levels. First is the relationship between medical personnel and patients. Government hospitals generate a large pool of patients from which government employed medical personnel source and secure private clients.

Doctors divert desperate patients they consider financially capable to private sector medical establishments they are affiliated to (or work for privately) or they reclassify patients as private even as they utilize the facilities of their employer which is a public organization. In the former case the hospital looses income directly whilst in the latter paltry /subsidized sums are charged for the usage of official diagnostic equipment whilst the larger part of fees charged is paid directly to the doctor (privately) for his expertise and medical supplies ie drugs and consumables they peddle directly to the patient. The natural consequence of this underground economy phenomenon is that the medical personnel, who are also in leadership positions at all levels of administration, are not aligned with the vision and mission of their institutions.

This informs their behavior and low productivity. Their side hustle or ‘galamsey’ which is illegal and destructive also corrupts non-medical staff who happily benefit from their own versions of this disruptive sub-culture. They have turned the medical institutions into bustling market places where deals and trades for medical services and consumables, beds, fake reports and non-medical services etc are negotiated at prices far above government approved rates. Somehow stocks from government ware houses find their way to the black market and the private sector.

Procurement at all levels is inefficient and based on ‘whom you know’ criteria. Payment for executed contracts is similarly treated by the finance departments thus practically bankrupting SMEs without the means to influence the system. Again this article paraphrases a warning by Dr. Kwame Nkrumah ie ‘ … that dangers arise out of Ghanaian public men attempting to combine business with public life …… those who cannot give entirely disinterested service should leave or be thrown out’.

It is instructive to note that the Ghana Infectious Disease Centre (GIDC), located at the Ga East Municipal Hospital, is the epitome of efficiency, exemplary commitment to duty and the alignment of employee and corporate goals precisely because the incidence of an underground economy is minimized. COVID-19, which is at present the main business of the GIDC, is a new disease the medical staff do not fully understand and so can not trade in on a large scale.

The effective tracking of patients and products purchased by hospitals and other establishments, as well as minimizing of financial leakage will stem the hemorrhaging of our health institutions.

This requires proper identification of goods and each patient who visits our health facilities as well as employees at all levels. Nyaho Clinic is operating a good and sophisticated system which we can study among others. We must comprehensively computerize and digitize the health delivery system and invest in strict auditing to expose the charlatans, increase efficiency and right size the sector organizations.

Finally, creating an integrated industrial base which meets the needs (consumables, wide range of equipment, medical expertise etc) of the local health sector is essential if we are to achieve and sustain a high level of performance and growth. Although the suggestion of specific lines of production requires deeper investigation and is beyond the scope of this article I acknowledge that this is a fast moving sector which thrives on research and innovative development in all its component spheres.

These include core medical sciences, diagnosis technology (medical &laboratory), pharmacology, health education, mental health, metal and wood fabrication, institutional management and applied technology etc. Instead of wholesale copying of strategies used by large markets / countries like China, India, USA and EU with forced levels of homogeneity and corollary benefits this article posits that smaller countries like Denmark, Finland, South Korea, Malaysia, Rwanda, Israel and Singapore provide us with smarter insights regarding development strategies in a competitive and globalized environment. We have more in common regarding their development problems and paths. Our struggle with management of our many and varied SMEs is paramount. How to grow them into larger and self-financing organizations with stronger balance sheets.

On both the Macro and Micro levels a closer look at our strengths and weaknesses as well as the weaknesses of our competitors, or different perspectives of clearly identified problems in the health sector will help point us in the right direction regarding specific projects.

Even as we concentrate on the local front as the basis for economic resilience we should have an eye on macro effects of AfCFTA opportunities as well as investment outside Africa (including the comprehensive African diaspora) which allow us to take advantage of medical markets and knowledge developed outside Ghana. This sharpens our competitiveness regarding use and upscaling of our God-given raw materials and enterprise.

The problem identification and problem solving skills or the entrepreneurial capacity of indigenous health sector investors, the question of scale and technical competence, questions of land acquisition and ease of doing business etc present difficult problems at the micro level.

These should be solved by investigating and building on known solutions (both macro and micro), a good dose of trial and error and R &D. Special and targeted concessions should be granted to indigenous investors, located in special clusters or designated areas, to attract their capital and expertise to the health sector. While developing core technology on the micro front, we should consider collaboration and smart investment by indigenous Ghanaians and the extended African diaspora. Of particular interest is the Israeli tactic of developing new skills locally and strategically investing in countries which provide conducive economic and scientific environments for growth and influence.

Today, crowd funding presents unique and innovative opportunities for exploring new technical frontiers and can be harnessed to expand this sector. These specialized industries created to serve Ghana’s health sector will allow us to develop higher paying and higher skilled jobs even as we export same by progressively integrating the three dimensions of the uncommon sense solution. We will definitely need to make adjustments for complexity, emerging problems and opportunities.

Hopefully, this article that emphasizes some old ideas and advocates new trajectories or new combinations of existing assets contributes to our charting a new course of action for sustained and resilient economic development.