Developments in ethnic conflict and secessionist agitations over the past decade are a cause for concern for countries in West Africa. The most recent of these being the declaration of a group of people declaing their independence in Ghana and calling themselves Western Togoland. It raises concern because they are interruptions to articulation of the state in the region. In this article we will look at the colonial legacy and its impact on what is happening generally and its potential to erupt if not checked, and also look at the Ghana case to see what lessons can be drawn from it.

Why should West Africa be mindful of these development? Below we examine some common denominators that make this rising demand a dangerous precedence for the region, given the potential effect for West Africa as a region which may be prone to seccession or iridentism if not checked.

A second reason is the possibility of terrorist groups taking advantage of these situations to infiltrate these seemingly innocous developments and create chaos in the region, as they have done in Mali. The training of private armies and small-arms proliferation creates a future danger for safety and security because they will become terrorists in the countries’ internal sovereignty and to the territorial integrity of states within the region. Unemployed youth that are trained to to use guns/bombs can become armed-robbers in the future.

The example of Mali is there to learn from. Will this relatively low-key rebellion in Ghana escalate into a more insidious phenomenon if not checked, as has happened in Mali? To attempt highlighting the reasons for apprehension and the need to nip this in the bud, let us examine why what is happening has potentially devastating impacts on Ghana and the West African region as a whole; it will be useful to look at the nexus between politics and ethnicity in the region.

General Characteristics of West African Politics

Since independence, the politics of West African states have undergone a lot of experimentation with with both regimes and the adoption of ideologies. However, underlying all the divergencies, the experimentations and flux which characterise the politics of the region are certain common charateristics. The obvious and most fundamental of these is their colonial experience. From this common denominator the various countries of the region have undergone a varied set of political regimes which can broadly be categorised into military regimes, one-party states and multi-party democracies. All of these have left their legacies on the patchwork of reality for present-day political intercourse in each country of the region.

Colonial Experience

Historical factors more than anything else have been very influential in determining both the structure and shape of states within the region. Colonial rule in particular has been the most significant in terms of the shape of politics since independence. As has been pointed out by many historians, the nation-state in Africa is a European creation – and West Africa stands out as the most heavily-demarcated region, in terms of the size and number of states, on the continent. It reflects more than any region in the world the legacies of colonial demarcation.

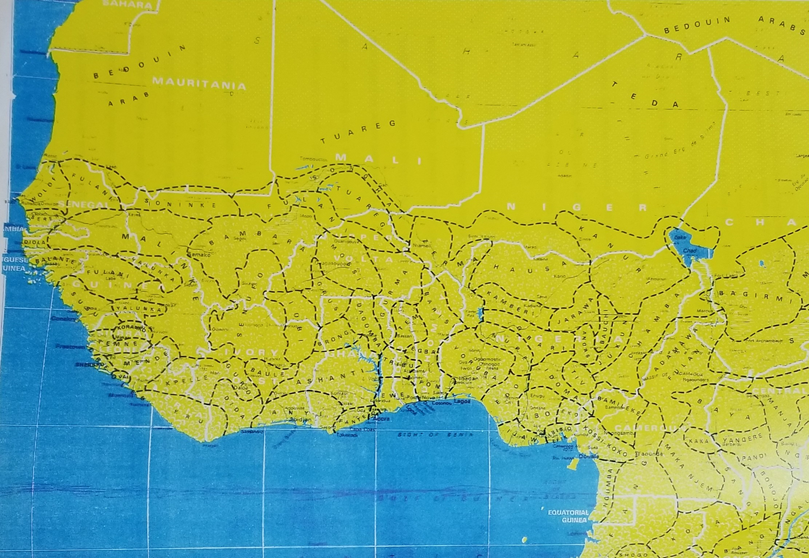

Ethnic and Political Map of West Africa

Of particular salience in the colonial legacies are the artificial boundaries that today determine the geographical extent of each individual country in the region. The effects of this has been the separation of ethnic groups into different countries. It has also created countries with very dissimilar economic resource bases and economic viability. The dividing of the same tribe-group into different countries and the agglomeration of different ethnic groups into the same country has created ethnically differentiated and amorphous states.

This situation was expected by several observers to result in a proliferation of secessionist movements and irredentism after independence. However, after an initial spate of ethnically inspired opposition of ruling governments, the situation settled down to what might be called a manageable equilibrium. Thus, apart from the Biafran war of secession (1967-70), the survival of colonially inherited boundaries has been remarkable.

One reason that may be responsible for the relative stability of the highly ethnically heterogeneous African state is that the agglomeration of diverse but numerically small groups within individual states has created a situation in which none of them dominates the political sphere to a disproportionately large enough extent to cause the other groups to view their continued political survival as threatened perpetually.

In instances where large and homogeneous groups exist and where there seems to be a disproportionate distribution of the benefits of independence, as was the case in Nigeria, communal conflicts occurred. A second reason for the survival of colonial boundaries is that West African leaders, like all other leaders on the continent, very jealously guarded the political independence of their territories; and in instances where such independence was threatened either by internal dissension or external aggression were not averse to protecting the boundaries and territorial integrity by calling on the assistance of former colonial masters. Leaders have helped each other, where they found it in their interest, to quell internal dissension.

Finally, the OAU entrenched in its charter of 1963 the principle of preserving existing colonial partition boundaries, and the notion that territorial integrity is identified with the state system became a basic premise of the emerging code of African international law. Thus, colonially inherited boundaries could not be redefined without effectively going against the spirit of the OAU. Hence, few attempts on colonial boundaries have ever been attempted, and where they have been, the only conceivable way of resolving them has been by reference to the colonial order.

Attempts at seccessiion, that is challenges to the colonial legacy, have failed largely because they have had virtually no support from other African countries. The result today is the existence of states where domestic politics is maintained by a careful distribution of state benefits in such a way as not to invite accusations of ethnic partiality.

Ethnicity and the state in West Africa

Are ethnically homogenous states possible in West Africa? It is my opinion that the idea homogenous groups have been divided between countries and lumped together, thus creating potentially unstable states, is somewhat exaggerated. Most ethnic groups are themselves highly differentiated group. The Ewes and the Akan of Ghana, the Yoruba and Ibo of Nigeria, and other tribes in the region are made up of similar but dialectically different groups.

The Asante Empire was anything but a nation made up of a consenting, willing and homogenous groups. Therefore, the colonial demarcation of the region should be seen not from a non-factual and sometimes romantic perspective of how the region would have been made up of peaceful coexisting ethnic groups, since that can never be proven. Also, it is difficult to see how national boundaries could be drawn to coincide with tribal boundaries.

The articulation of the nation-state, properly so-called, is still in its embryonic stages in almost all countries of the region. Their sovereignties are more juridical than de facto. Peace and security are a result of policies that encourage authority and legitimacy transfer from groups to the state rather than the ethnic group. The nation-state or a pluralistic security community takes time to build and must be deliberately undertaken for centuries. Countries in the region are not focusing energy on building their countries into nations where a deep level of a psycho-social community exists.

As the the map shows, West Africa in very heterogenuous. If tribal boundaries had been followed, the sizes of states in the region would have been even smaller than they are today. Thus it would have been difficult, no matter who demarcated the region, to have ethnically homogenuous states. The ethnic, and more specifically the tribal diversity of states, is inevitable given the patchwork of tribal boundaries in the region. It can indeed be said that the straddling of tribes across borders is also inevitable. What was not inevitable is the size of the countries.

Further Dividing of Inherited States

Many of the countries balkanised themselves further by creating regions that further disaggregated the state along ethnic lines, thus eventually making national integration even more difficult. The Mali Federation between Senegal and the then-Soudan (now Mali) also broke up because of personal and ideological differences between Senghor and Keita – just as politics in Nigeria was stymied by the personal differences between Awolowo, Azikiwe, and Amadu Bello. Thus West Africans could not sustain cooperation in instances where it was attempted, and broke up even more in certain instances where it had existed prior to independence.

Boundary Demacation and Ewes and Unification

Countries in West Africa are creations of European colonialism and imperialism. Ghana as a country did not exist before the advent of the Europeans. First, it was the British initially coming into the Anlo lands in 1850 and settling more permanently in 1874. They then moved along the coast eastward gradually; and did not, according to political historians such as D.E.K. Amenumey, occupy the whole Ewe-speaking territory immediately.

It was only when Germany came on the scene that more aggressicive steps were taken to occupy the rest of the Ewe-speaking territory and establish British rule over them. There was a rush to more or less estsblish ownership over the Ewe speaking territory. The squabble over land between the British and Germans resulted in a boundary demarcation between the two colonial powers that resulted in splitting the territory of Ewes between the two colonial powers.

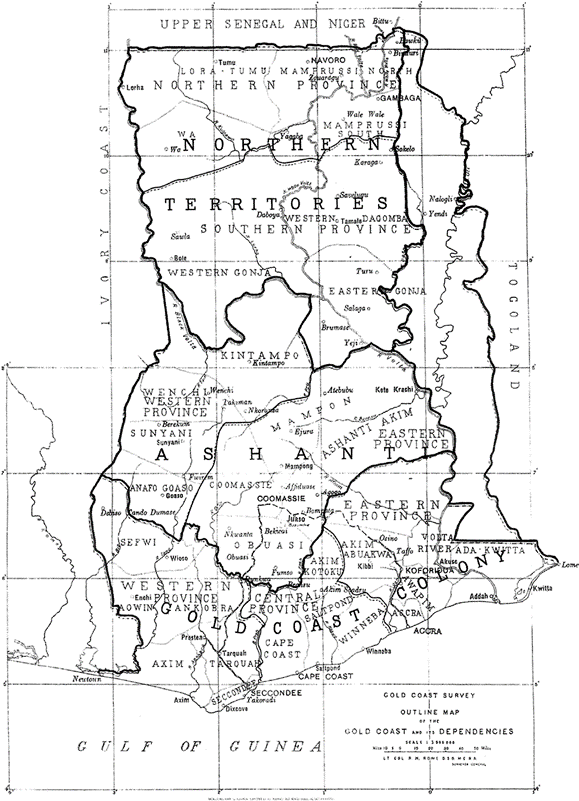

The states of Anlo, Some, Klikor, Peki and Tongu remained part of the Gold Coast, while the others became part of the German Protectorate of Togo. Apart from the , other ethnic groups that were split by the demarcation included the Kusasi, Mamprusi, Dagomba and Nanumba among others.

In the map above, we have shaded British Togoland to indicate that when the literature talks about the southern part of British Togoland, it is not referring to southern Gold Coast but instead to the Ho and Kpando areas. The Anlo areas have always been a part of the Gold Coast. Hence the Anlos, Somes and others in the southern part of the Gold Coast were not part of the plebiscite that decided on the integration of British Togoland into Gold Coast after the latter’s independence and change to Ghana.

But back to the story: when the demarcation between the British and Germans happened, the Ewe states and their chiefs protested against the partitioning of their states. Kwadzo Dei VI protested strongly against the splitting of his state and managed to be exempted from being affected by the demarcation. Others protested too; such as the chiefs of Adaklu, Abuadi, and Waya, but they were forcibly brought under German control. Even though the capital of the German administration was in Lome, there were District Officials and their supporting police forces in places like Ho and Kpando.

Ewe economic activity prior to the advent of the Europeans was highly integrated. Foodstuffs, salt, fish ecetera were constantly exchanged among the various areas within Eweland and beyond. The demarcation of the land under different foreign administrations created obstacles to free trade. Political administrations superimposed on states within Eweland also created problems for chiefs whose peoples were now under different jurisdictions, British and German, whose attitude to traditional rule were different.

There was also the different languages that the separated people had to work with as their official languages. The differences in administration – harsher German versus the more linient British rule – caused the Ewes in German Togo to desire joining their kin in Ghana. Many families among the Anlos and Somes had families in Lome, the German administrative capital. There was therefore constant interactions between them. The Ewes under German rule wanted to move to join their kith and kin across the border in the more congenial Gold Coast.

These and many other reasons led to the calls for Ewe unification. The unification was for all Ewes to be under the same British colonial administration.

The World Wars and Changing Face of Ewe Unification

During the first World War, Togbe Sri II of Anlo whose kingdom was not split by the demarcation but was vehemently against its effects on the Ewes as a whole, actively assisted the British with the hope that if Germany was defeated the Ewes would be able to come under British rule. Unfortunately, after the defeat of Germany the area they occupied was split between the British and French under the League of Nations. The Ewes under Germany were now in French Togoland and British Togoland. The status quo had not changed. Various petitions were written to the Gold Coast Colonial Administration and to the UK government to no avail. Deputations even attempted going to the League of Nations, but that did not change the situation either.

The defeat of Germany only resulted in a further split of German Togoland into the two Protectorates. Ewe unification was not embarked on by Ewes alone. As D.E.K. Amenumey noted in his book ‘Ewe Unification’, prominent non-Ewe-speaking people from the Gold Coast – such as Caseley Hayford, Ofori Atta and other non-Ewes – represented and advocated for their cause in various fora. Initially, Ewe unification was never about secession or iridentism. It was about bringing Ewes under one colonial administration.

After the defeat of Germany again in World War 2, the two Togolands became Trusteeships under the United Nations. With the Truseeship system, there was an expectation that the colonial powers would prepare the Trust territories for eventual independence. Under the UN Trusteeship arrangement, various possibilities were considered for the Trust Teritories. These included: integration of British Togoland into Gold Coast at independence; the unification of British and French Togolands into one country and the original concept of unification. The dilemma for the colonial powers was how to treat the Ewes differently from all the other ethnic groups that had been split but had not advocated as vociferously as the Ewes.

The points to make here are that: Ewe unification started as a result of the European scramble for Africa; unification was not about secession or iridentism; the Anlo Ewes on the coast were never part of British Togoland, and therefore did not take part in the plebiscite of 1956; The Anlo Ewes have always been part of the Gold Coast and subsequently Ghana; and also southern British Togoland does not mean southern Gold Coast.

The plebiscite that eventually took place to resolve the conumdrum resulted in a 58% majority of the people opting for integration with Gold Coast. Out of the five districts that voted, only two of them, Ho and Kpando, preferred remaining separate with the prospect of being unified with French Togoland as a unified country.

Current Incidents of Secession

I believe the various secession movements, such as among the Tuareg in Mali and the Ewes under the Homeland Study Group Foundation pose dangers for the territorial integrity of states in the West African region for the following reasons. They challenge sovereignty of the state by attempting to carve out new states from those that exist now. Western Togoland never existed as an entity. It is an atavistic move based on an idea that never existed in reality and on a false 50-year legal clause that cannot be supported by evidence.

The ethnic group, which is our main concern in this article, is a large and unwieldy sort of social organisation. Within it are a motley collection of more intimate territorial, religious, and political affiliations. However, the nearer one moves toward the more intimate level of social interaction the less effective they are in terms of their impact on policy at the state level. Hence, a village elders’ meeting or even a traditional court is less likely to influence political decisions than the possibility of ethnic unrest.

The vertical interaction between society and the state is facilitated by the structure and various mechanisms of political intercourse. There must the mechanism for state interaction with the publics. Where this is absent, it creates a break in interaction and communication. The chiefs ought be the link between the political centre and the people. MPs are unable to perform this role because of partisan politics.

Ethnicity: Definition, Concepts and Characteristics in West Africa

The diverse ethnic composition of West African states is seen as having multiple ramifications for national unity and political stability for countries in the region. In all instances where an explanation for the political and economic malaise of West Africa is attempted, ethnicity usually features as an important variable whose impact is seen, largely, as negative. It is my contention that though ethnicity has and continues to be important in the economic, social and political organisation of the state in West Africa, things have changed considerably since independence.

There is a general assumption that ethnicity is a bad thing. This negative connotation pervades the analysis of its impact on states. Contrary to popular belief, I think ethnicity was an important organisational principle prior to colonialism and in the early days of state formation in West Africa. This is because it provided an easily recognisable structure for governments to use in their interaction with their societies.

Ethnicity is difficult to define, however. The reason for this is because of the multidisciplinary approach in the study of the concept. Various perspectives – ranging from those of anthropologists to political scientists, sociologists and historians, have created a kaleidoscope of insights into the concept.

One way of looking at ethnicity is to list the bases of ethnic distinction as including the possession of a symbolically different geographical origin. This could be historical or recent, and is of prime importance because it provides the basis of differentiation. Other elements include historical traditions, social customs, languages, physical appearance and religion. However, the essential element in ethnic distinctiveness is that it is ascriptive and describes an overlap between cultural and territorial segmentations of society.

The second way to look at it is to see ethnicity as organised activities by persons who jointly seek to maximise their corporate political, economic and social interests. What this suggests is the deliberate exploitation of ascriptive affiliations, and introduces a dynamism and utilitarianism to the concept. Apart from the ascriptive criterion which forms the basis of organisation of ethnic groups, this perspective looks at ethnic groups as interest groups.

Both the dynamic and static aspects of ethnicity that have been highlighted by the definitions above can be traced to its effect on internal political interaction. First, the multi-ethnic composition of individual states has meant a concentration by national governments on nation-building and the forging of state unity and nation-building. The straddling of ethnic groups across borders of neighbouring countries such as the Ewes of Ghana and Togo creates a continuous socio-psychological space which ought to facilitate neighbourliness among countries of the West African region.

The paradox is that it also creates situations of possible irredentism and secessionism. Added to these, because the straddling of ethnic groups make international boundaries permeable, such occurences are seen as having implications for national security. So, instead of being viewed as a positive part of the political landscape, it is viewed mainly as negative.

The first proposition that ethnic heterogeneity is destabilising for the internal structure of countries is based, implicitly, on the idea of the ethnic group being an interest group which seeks to promote the collective goal of the group at the expense of other groups within the country. This sees inter-ethnic interaction mainly as conflictual.

If the ethnic group is indeed a consciously organised group which seeks to further the interest of its members, then the framework within which such groups function, the rules governing state/society interaction, and the characteristics of the public domain in terms of the scarcity or the availability of distributable resources could be posited as important elements in ethnic organisation, compromise and conflict.

The framework which makes up the level of ethnic segmentation and determines the intensity of the interaction between the various groups and between them and the state is provided by the relative size of ethnic groups within the country, the number of such groups, their settlement patterns within society, and the extent of overlapping or cross-cutting.

Additionally, the way in which the state is organised, in terms of leadership style, ideology, and institutional structure, will affect the salience of ethnic conflict in determining access to distributable resources. The intensity of ethnic cooperation and conflict and its salience in resource distribution is affected also by broader societal factors, such as socioeconomic change, political organisation, or government policies.

Implicit in the negative perception of erthnic groups is the assumption that the ethnic group is unified and cohesive. However, this tends to be far from true. Ethnic groups are fluid and lack homogeneity and cohesiveness. Hence, there is no common (indivisible) interest of its members. The lack of cohesiveness and the espousal of common interests may sound contradictory and paradoxical. Such discrepancy is only because government resource allocation is designed – where it is to curb actual or potential conflict – to appeal to the group as a whole and not to individuals, since individuals are in themselves not as threatening to national unity as the group is.

The second characteristic of ethnic groups is their heterogeneity and lack of cohesion. This means that individuals identify themselves with a segment of the group in certain instances and with the whole group on other occasions. In Ghana, for example, the individual may identify himself with the Akan as opposed to the Ewe at the state level. However, at the cultural, linguistic and territorial levels he may identify himself as an Ashanti as opposed to a Fanti – even though both groups fall under the broader Akan ethnic group. The ethnic group in West Africa in certain instances is therefore a broad category. Even though Ewes can be classified as an ethnic group, differences exist in dialects, religion, cultural observances etc. Variables are therefore capable of being refined even further to differentiate between co-residence in a region, economic activity and other types.

The heterogeneity of the ethnic group also means that individuals belonging to different ethnic groups are able to identify with each other in other group-formations such as social class, religious groups and trade unions – all of which cut across ethnic boundaries. Thus, an analysis of the role of groups in the politics of West African countries must be done with their internal structure in mind.

Despite the internal divisions and changing form ethnic groups adopt under different circumstances, they have been and continue to be highly significant politically. What intra-ethnic schisms indicate is the complicated politics of the region.

Another aspect of the internal diversity is its impact on intergroup exchange. Instead of a two-way bargaining process between ethnic groups and central government, there is in most instances several layers of interaction in the process. The first takes place within the ethnic group itself at the required level and its centre, with the second part being that between the ethnic bloc intermediaries and national leaders at the top.

The third and final characteristics of the ethnic group we need to look at is that it promotes the communal interest as opposed to the individual interests of its members. Through them, demands by an ethnic group to secure railway facilities or roads are made. Such demands are indivisible. However, though ethnic intermediaries represent collective demands at the governmental level, it is not uncommon to find government ministers appropriating resources for their area of origin (hometown); sometimes to the exclusion of other segments of the same ethnic group. This is because the intermediary tends to get the most political support from his immediate hometown.

As was mentioned earlier, ethnic demands are usually articulated by the elite and are usually urban-led. The demands normally take the form of a reciprocal exchange between central authority and the intermediaries who represent ethno-regional interest according to what they perceive those interests to be. If we take Members of Parliament in Ghana as an example, the question would be how intimately they are aware of the collective interest of the areas they represent at the national level. Ethnic cleavages are regarded by most leaders who oppose them as divisive. In a lot of instances national leaders have voiced their opposition to such arrangements.

Because of the negative effects attributed to it, national leaders in the quest to foster national unity have used several devices to reduce its salience in national politics. This they did by attempting to weaken ethnic linkages, and by creating common national ties, remembrances and values. Thus, public policies abolishing chieftaincy in Guinea, ethnically-based political parties in Ghana, and the banning of state-creation movements in Nigeria and Ghana were all attempts to overcome divisions and keep such cleavages in check. So the formation of single-party states were attempts to overcome what, among other things, were perceived to be the detrimental effects of ethnic fragmentation.

Despite the public pronouncements against ethnicity, leaders usually took and still take proportionality principles into account when dispensing political appointments and in fiscal allocations. Thus, though central-state elite sometimes view ethnoregional negotiations as burdensome, they still regard it as a necessary form of political exchange. This is to a certain extent explained by what has been called ‘the softness of the West African State’. The inability to impose its regulations, and thereby exact compliance by threatened coercion, makes ethnic allocations a useful means of enhancing legitimacy.

Ehnicity, Political Structure

The role of the elite in ethnoregional bargaining and the structure of politics at the centre have implications for national unity.

It must be remembered that the elite who champion ethnic causes are themselves members of the ruling class, and that the impact of ethnic bargaining is different in single-party and no-party states. It must also be remembered that ethnic conflict does not only occur when resources are perceived as being disproportionately allocated in favour of a particular group. Ethnic groups may conflict with central government as the latter seeks to overrule the prerogatives of traditional rulers in such issues as land redistribution and ownership.

The role of the political elite and the public in making ethnicity a salient aspect of politics in West Africa is another aspect that is important. Political aspirants have and continue to use the ethnic group as the focus of their support, and usually articulate their campaign rhetoric in a manner that is meant to appeal to ethnic sentiments. Symbols and remembrances are evoked to buttress the idea of ethnic cohesion and the need for unity.

The ‘we’ versus ‘them’ has come to dominate West African politics because of the tendency for the political elite to depend on their ethnic group for support. Election to parliament depends very much on being able to win the vote of one’s ethnic group. This has gradually had the effect of leading the public to expect parliamentarians to champion the particularistic interests of the ethnic group. Post-colonial ethnic conflict is elite-led.

In multi-party systems, regional representatives sometimes find themselves on the opposition benches. This means that regional/ethnic interests are not represented in the ruling party. The result of such a situation is that it takes a lot of effort to get fiscal allocations. This is mainly because governments tend to allocate resources in a way that will enable them to retain their support base. In an instance when most of the MPs from a region find themselves in opposition and where such a region coincides with ethnic allegiances, conflict between central government and the region may arise as the ethnic group feels itself discriminated against.

To the extent, therefore, that ethnic organisation is fluid and heterogenous, and politics itself dynamic, it is difficult to assess the direct impact of ethnicity on national unity. This is important because it implies that ethnic diversity does not preclude the formation of a political community. The United Kingdom, Canada or Spain, for example, are not ethnically homogeneous states. Despite the conflicts that arise between different ethnic groups in these countries, they are nevertheless regarded as constituting political communities.

Cultural homogeneity is therefore neither a prerequisite for political unification nor a sufficient condition. We suggest that it is only in instances where political parties are polarised along ethnic lines, and one particular ethnic group always dominates the decision-making machinery that ethnic conflict might become endemic and therefore stymie political unification

Ethnicity and Nation-building

Nation-building in West African countries has gained ground since independence, and identification with the state has increased while the salience and probability of ethnic irredentism has waned and reduced as governments devised ways and means of distributing resources.

It is true that ethnic diversity posed very serious problems for West African states in the first decade of independence as each ethnic group sought to assert itself politically. It is also true that an actual secession attempt was made by the Biafrans of Nigeria which led to war between 1967 and 1970. The recent Tuareg attempts at secession in Mali have resulted in fighting within the country. Furthermore, it is undeniable that politics, even today, are still influenced to a large extent by ethnic loyalties. Irredentist claims made on the Ewe-speaking section of Togoland after the latter’s independence caused a lot of apprehension in the 1960s and led to a souring of relations between the two countries. However, despite all the problems that arose and are still present, the colonial boundary has become a permanent feature of the region with no modifications. Indeed, they are seen as among the most resilient colonial inheritances to date.

To examine the issue of the idea of the nation, we conducted a piece of research in the 1960s. In that research, we asked Ghanaians, Nigerians, Togolese, Ivorians, Sierra-Leoneans and Liberians living in the UK whether they saw themselves as different from other people from other states of the West Africa region. There was an unequivocal and unanimous ‘yes’ response from all the respondents. Not even one respondent differed from this position.

We then asked if they were willing to fight for their country against other countries such as Burkina Faso, Togo, Nigeria and Mauritania; the answer was again a unanimous ‘yes’.

We then went on to test the relative affiliation to ethnic groups vis-a-vis the state. What came out was that political affiliation of Ghanaians questioned saw political allegiance at two levels; the international and the national. Ghanaians from all ethnic groups saw themselves as Ghanaians when the comparison was with people from other countries. At the national level, social and political identification were not so clear-cut. Not all people from an ethnic group identify with the same political party, even though the tendency was to support candidates from ones own ethnic group.

Ethnic affiliation is predominantly a social differentiation which spills over into political identification if political parties are ethnically based. The reasons given for identifying with political parties that are dominated by people from the same ethnic group range from affective feelings to utilitarian expectations that resources and political positions will be more likely to be distributed in favour of people from the ethnic group of an incumbent. Others supported political parties solely on the basis of whom they thought could do the job better.

At the national level, it was however clear that those questioned did not see the ethnic group as more important than the state. The two were different social constructs overlapping at certain times. The validity of the state was not being questioned. The ethnic group and the state were not in conflict. Neither is ethnic conflict endemic. Resentment arose when inequity was perceived in the distribution of resources in favour of the incumbent’s ethnic group.

The conclusion that ethnic identification and political allegiance do not always coincide is validated by research carried out to test the validity of the assumption that the straddling of tribes across borders creates irredentist and secessionist tendencies, and therefore leads to instability. Research, though dated now, among the Ewes of Ghana and Togo revealed that the straddling of tribes across borders did not necessarily result in secessionist tendencies among the general population of those tribes.

When we asked Ghanaian Ewes the question: “Whom do you identify with more, Togolese Ewes or people from other tribes in Ghana?”, 99 out of 100 people in the age group 40 to 65 years responded that they identified with Togolese Ewes more than with people from other tribes in Ghana. When the same question was put to Togolese Ewes of the same age group, they all said they identified with Ewes across the border than with other tribes in Togo. There was therefore mutual identification with each other across the common border. When the same question was put to people between between 15 and 39, the answer varied with the level of education, the distance they lived away from the border, their perceived future prospects, where they attended school, and whether they could speak the Ewe language.

We found that the further the respondent lived from the border, the higher the level of education, if he/she attended school in other parts of the country other than Ewe areas or there was a good mix of ethnic groups, if one perceived his or her prospects to be good and not threatened, and if he/she could not speak the language, then the level of identification with those across the border was minimal or even non-existent. They did not see any overwhelming sense of belonging together culturally, and neither did they see their futures converging. On the other hand, those who lived closer to the border or had relatives in either country, were less educated and could not speak the languages of the other tribes and had not mixed extensively with people from other tribes tended to identify with their tribesmen across the border. However, their identification was cultural rather than political.

When we asked the 40 to 65 age group why they identified with each other more than with people from other ethnic groups from their own countries, the predominant answer was because they shared the same culture, language, religious practices and that they had relatives living on the other side of the border. Particularly for Ghanain Ewes who did not speak English or any of the languages of other tribes in Ghana and Togolese Ewes who were in the same position, language was a very important criterion for identification. The Ghanaian Ewes actually felt more at home in Lome, the capital of Togo, and went there more frequently than to Accra because Lome is in an Ewe-speaking part of Togo and it is closer. Another reason, especially among the elite of both countries, was that they felt discriminated against by other tribes from their own country.

When asked whether they felt the Ewes of both countries should be united into one country (Ghana or Togo) or secede from both countries and form their own new state, all except one person said ‘no’.

The reason for the apparent ambivalence was explained by separating socio-cultural identification from political identification. Most of those questioned did not see any special advantages accruing from such a move. A large number thought such an occurrence would actually lead to retrogression. One reason for the perceived negative impact of such a move was that since official business was conducted in European languages in the region, they would have to adopt either French or English as the lingua franca. If English were adopted, the Ghanaian Ewes would be at an advantage in terms of jobs and political office and vice versa. Thus, the common language factor would not produce any substantial advantages except in social communication.

The separation of political and cultural affiliation was validated by the fact that Ghanaian and Togolese Ewes were willing to fight each other if war erupted between armies of the two countries. The reason for their willingness to fight was that they would not go around asking if an enemy was from their ethnic group or not. The enemy from the neighbouring country would be treated collectively rather than as possibly members from ones own tribe. Intra-ethnic conflict that approximated war was seen by respondents as remote. However, if it should occur it is likely to be contained by the separate national governments.

Another reason that was given for not wanting to join to form a separate state was intra-ethnic rivalries. It was pointed out that the Ewes did not constitute a homogenous group except from a distance. Besides, Ghanaian Ewes generally felt superior to their counterparts in Togo – while the Togolese Ewes felt Ghanaian Ewes were scamps.

Both groups of Ewes also felt they had lived so long in their individual countries and therefore identified with the state and other groups within it politically. Of the more than 100 people interviewed only one person was willing to fight a war of secession, but expressed the unlikelihood of the need or occasion ever arising. It was also pointed out that having established economic, social and political links with other groups in the individual countries since independence, it was indeed very difficult to envisage giving it all up for the possibilities of living in an ethnically homogenous state – a situation which did not promise any obvious advantages. Neither group of Ewes was therefore particularly interested in forming a separate state of their own, even though they expressed a liking for the idea of free interaction between them as a result of regional integration.

Even though there is clearly no desire on the part of the Ewes of Ghana and Togo to either separate to form their own state or be united with their kin in either country, their straddling of the Ghana-Togo border has contributed to the sometimes acrimonious relationship between the two countries. Though the Ewes expressed the desire to be united after the Second World War, and even made representation to the United Nations on the issue, such demands have become dormant. The present generation of Ewes have lived in the respective countries since they were born, and have therefore become politically integrated into those countries. This, we deduced, explains to a certain extent the difference in answers of the two age groups.

From the above we concluded that political communities were being formed in West African countries. Though the ethnic group remains an important group for individual identification and group action, political loyalty was with the state rather than the ethnic group. A nascent political loyalty to the state is developing, which makes the assertion that African states lack empirical statehood is anachronistic.

Apart from the Biafran war of secession, no country in West Africa has been faced with break-up because of ethnic diversity. Governments continue to be the only legitimate users of coercive force. In the Liberian civil war, the issue is not about the legitimacy of the state but about power and resource distribution, and ethnic discrimination. But even in this case, ethnic groups continue to identify with the state.

Our conclusion is therefore that states are not at risk of disintegrating because of their diverse ethnic composition. Neither is the straddling of tribes across borders a threat to survival of the state in the region, though it might be if there is discrimination in the allocation of resources.

Politicians in West Africa are aware that the state is no longer a mere inheritance from the colonial era. They are however mindful of the effects of their policies on perceptions about equitable distribution of political appointments, executive positions in parastatal organisations, project and resource allocation – and are also careful of making utterances that could be construed as indicating ethnic bias.

It must be stressed that though the idea of the nation is gaining ground slowly, the ethnic group continues to be an important object of identification. It is the predominant reference group in social organisation, and has not been replaced by class identity on a sufficiently general level. Even in the urban areas where social assimilation has been highest, individual ethnic/tribal associations perpetuate links with the hometown and ethnic groups.

Ethnic organisation is, in our opinion, an important organising principal which could serve very well in a political situation where pressure groups and lobbies are not well developed. Governments adopted a negative attitude to ethnic demands, in part, because many politician’s could not come to terms with potential alternative centres of autonomous power; and, we suggest, did not know quite how to incorporate and assimilate such sources of opposition into the ruling party’s proposed structure of the state or the bureaucracy during the early days of independence.

Without ethnic pressures, it is difficult to envisage how governments would have been mindful of equity in the spatial distribution of resources without a bias in favour of areas where they got the most votes. Our conclusion on ethnic pressures is that it was a useful means of expressing general demands. It’s conflictual and potentially disintegrative impact on national politics and survival of the state could, to a certain extent, be because nationalist governments failed to realise that the nascent pluralistic political systems that had been introduced on the eve of independence by the departing imperial powers were in part dependent on finding compromises between groups and bargaining between conflicting interests.

Sensitity of the Ghana/Togo Border

There is no doubt that dissidents escape from one country to another all over the region, and that this is sometimes facilitated by the straddling of common borders by the same ethnic group. Tribes across borders have not in every instance been a problem for neighbouring countries. The Ghana/Togo Border, for example, has experienced one of the most protracted tensions because of this issue. However, from our research we found that the tension was not caused by straddling of the same ethnic group across the common border, but by coincidences that have combined to make that boundary important in the strategic calculation of both countries.

The factors that have combined to cause tension on the Ghana/Togo border include: the nearness of the Togolese capital to the border, the internal impact of ethnic identification in politics, and the difficulties that arose between Nkrumah and Olympio over the unification of Ghana and Togo after the latter’s independence.

The capital of the Togolese Republic is only about four miles from the border with Ghana. This means that dissidents find it very convenient to penetrate the country from Ghana. The capital is also situated in Ewe territory. Ayadema, the president of Togo, at that time regarded the Ewes as his main political opponents. A large majority of Ewes also feel that Olympio, an Ewe, was overthrown by the active participation of Ayadema, a Kabre. Part of the Olympio family, and the first president’s son, who had pretensions toward ruling Togo lived in Ghana.

Thus, even though the general Ewe speaking population around the border are apolitical, the coincidence of the factors listed above combined to create suspicion of the Ewes in Togo by the ruling predominantly Kabre government. The border was therefore regularly closed and accusations of political connivance were made regularly, especially, by the Togolese government. As long as the Togolese authorities perceive an Ewe threat, the border will continue to feature highly in Togo’s strategic calculations. Indeed, the situation could actually be reversed if rulers of Ghana perceived their main opposition to be the Ewe and there is an Ewe president in Togo.

The straddling of tribes across borders does not therefore pose the problem attributed to it in the region. The problem is mainly a result of the personalisation of politics, and in the Ghana/Togo case a combination of historical, cultural and ideological factors.

Conclusions

As we have indicated in this article, the current threat to Ghana’s sovereignty by the Homeland Study Group Foundation led by Charles Kudzordzi is based on history that is false. Western Togoland has never existed and is a figment of his imagination; and neither was there any 50-year limit clause in the plebiscite after which the Ewes could decide to form their own state. As we pointed out, not all Ewes were part of British Togoland. The Anlo, Some and Peki were part of the Gold Coast and part of Ghana from its very beginning. Clearly then, whatever conditions that could possibly have existed was not for all Ewes. The case for unification is based on an atavistic appeal to primordial relations that never existed.

So, what should we make of it? Should events since 2016 be dismissed as the dreams of a dotard which will eventually die down? This would be a mistake. The fact is that Kudzordi has been able to convince people to believe his rewriting of history – and even some educated and elite Ewes sympathise with his cause. The Group uses social media and the Internet to propagate its doctrine; and lest we forget, has been able to train a private army.

I believe the group has been testing the waters. They get bolder and bolder as they get treated with kid-gloves. If indeed the images we see on the Internet of a private army are true, then the country must do something about this before it gets out of hand

As noted, the colonial legacy is a severe balkanisation of the region which leaves the possibility of secession and irridentism. This is because of the ethnic heterogeinity of the states and the stradlling of tribes across international borders. As already suggested, these will only lead to secession and irridentism if resource distribution in a country is seen as unfair. In Ghana, the distribution of resources is seen as skewed by the Ewes. They feel taken for granted by the NDC party that they vote for, and neglected by the NPP who do not have a strong presence in the region.

The boarding-house system was also an important tool for assimilating Ghanaians from different tribes. People from various tribes lived together and got to know each other. Life-long friendships were fostered among students and their teachers. The point here is that nationalism must be built deliberately to foster unity and to reduce the ‘we’ versus ‘them’ effects of tribalism.

In conclusion, the current spate of ethnic conflict in Ghana may seem innocous but can easily become insidious if not checked. For the long-term, the allocation of resources must be done in a manner that ensures all have a fair share in the national cake. Finally, chiefs must desist from political utterances that may be construed as ethnically-based political endorements.

The writer is the Managing Director of Zormelo & Associates, a Management and Development Consultancy Firm in Ghana, and also Chairman of the Upstream Oil and Gas Service Providers Association of Ghana