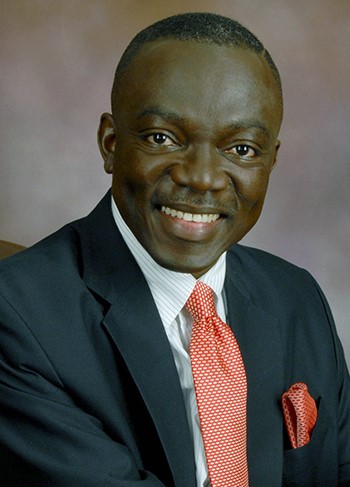

Strategic Sourcing and Industrialisation insights with Prof Douglas Boateng

Africa is one of the fastest growing consumer markets in the world, yet spending habits on the continent remain an obstacle to long-term industrialisation and economic development. The adoption of more strategic consumer sourcing and buying behaviors may offer greater opportunities for economic regeneration following the unprecedented impact of COVID-19.

Despite recent slowdowns in the global economy, the appetite for consumer goods and products in Africa remains strong. Ghana, Nigeria, South Africa and Kenya are no exceptions. A recent Brookings Africa consumer market report found that household consumption in Africa is increasing faster than its GDP and its annual GDP growth continues to overtake that of the global average. The report indicated that consumer spending on the continent has grown at 3.9% year-on-year since 2010 and amounted to US$1.4 trillion in 2015. McKinsey predicts this figure will increase to US$2.1 trillion by 2025.

Food and beverages according to McKinsey constitute the largest consumption category in Africa, with as much as one-third of Africa’s household income going towards this consumer category. A further 15% of consumption is connected to non-food consumer goods such as household goods, clothes and motor vehicles.

What African consumers buy, where they buy from and how they make decisions related to their buying practices all have a significant impact on local and regional industrialisation, socio-economic development and job creation for the current and future generations.

So, when an African consumer decides to buy a fruit juice, rice, maize, canned tomatoes, shirts, belts, underwear or socks, one wonders whether they check to see where these products come from and whether their buying practices are focused purely on price issues that satisfy short-term needs or helping to create forward and backward demand for locally based companies and associated supply chains.

As the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) comes into effect it will open up a single market for consumer goods and services – enhancing opportunities for trade and local production, and also opening up new avenues of consumer spending. It is also predicted that this new market will comprise a total of 1.7 billion people by 2030.

In October 2019, the World Bank estimated that Africans generally live on less than US$5.50 per day. The international poverty line benchmark used to monitor people living in extreme poverty in the world is US$1.90 per day. US$3.20 and US$5.50 are relatively higher benchmarks that demonstrate national poverty benchmarks in lower and upper middle-income countries. Assuming that only 60% of this predicted population (1.02 billion) could afford US$1.90 per day sourcing for their basic needs, this on an annual basis (~250 days) could represent approximately US$484 billion spend within value chains in various African economies every year.

In Ghana, if 60% of her citizens (i~18.6m) are continuously encouraged to spend at least US$0.61 cents(~3.51GHC) per day for 250 days annually by strategically sourcing locally produced consumer goods, it conservatively equates to US$2.82 billion (GH¢16.4 billion Ghana) annual spend on various Ghana based production supply chains. The billions of dollars or its equivalent in cedis will thus be circulating in the local economy positively impacting various national initiatives including the one district one factory projects.

A fascinating possibility would be to think about what would happen across Africa if the majority of its consumers with disposable incomes began to view their personal buying behaviours as if they were strategically sourcing. That is, if they started to adopt a form of strategic consumer sourcing that is focused on selectively sourcing African produced goods and services.

If African consumers start to become strategic when sourcing their goods and services, they could help to collectively leverage local, regional and continental spending to economically benefit the region and continent as a whole.

At the moment Africa by and large consumes what it does not produce.

For example, a recent study conducted by PanAvest and Partners found that unlike in Europe, India, China and the USA, over 90% of the clothes worn in Africa are imported from countries outside of the African continent, primarily India and China, and increasingly from other developing nations like Turkey and Bangladesh.

Over 85% of the footwear worn in Africa is sourced from outside of the continent including India, China, Turkey, Brazil and the Dominican Republic.

Over 90% of the underwear worn in Africa is imported from amongst others India and China.

In other key economic sectors, the same pattern exists. Over 70% of bulk pharmaceutical, vaccine, nutraceutical and cosmeceutical needs are sourced from outside the continent. Over 75% of white goods (air conditioners, refrigerators, stoves etc.) are brought in from outside the continent, again primarily from China, South Korea, Germany and India.

Over 50% of loans sourced for infrastructure development originate from outside of the continent. Any interest that would have been earned on such loans by African banks is lost, and over 70% of the content in educational textbooks also originates from outside the continent.

Comparatively, Africans spend more money outside of the continent than any other grouped population in other regions of the world. One of the key reasons for this is that when it comes to acquisitions in Africa, the unit price is often the first consideration before anything else.

Over the years, this short-term thinking and price focused buying behaviour has led to the spectacular demise of selected industries on the continent including the textiles and clothing industry in South Africa, tomato processing in Ghana, footwear and socks in South Africa and Nigeria, educational book production in Ghana, furniture production in Nigeria, Tanzania and Ghana, fruit processing in Tanzania and underwear in South Africa, Tanzania, Ivory Coast, Senegal, Mali and Ethiopia, to name but a few.

The African textile industry continues to struggle in the face of the very low-cost products imported from China, Korea, India and Bangladesh where there are low labour costs and often poor working conditions.

According to statistics from the South African Department of Trade and Industry, China’s share of the country’s total imports of clothing and textiles grew from 16.1% in 1996 to 60.7% in 2008. Estimates also indicate that in the last six years, up to 69 000 jobs have been lost in the clothing and textiles sector in South Africa; a drop of 39%.

The Southern African Clothing and Textile Workers’ Union reaffirmed that due to the relatively cheap imports, employment in the sector over the last 15 years had dropped from approximately 200 000 people to about 90 000.

There are similar industry sector-specific challenges in Tanzania, Zambia, Nigeria, Ghana and Kenya. The region’s footwear, furniture, underwear, book publishing, textile and clothing industries have virtually collapsed whilst the meat, poultry and salt industries are under increasing pressure.

With relatively no economies of scale, selected manufacturers of locally made and sourced goods and services, especially in consumer industry verticals like agriculture, food and beverages, continue to struggle to compete on price.

Based on extensive seven-year purposive fieldwork in selected countries, it was found that the probability of the African consumer overlooking price and strategically supporting the relatively more expensive locally-produced and on par quality products is less than 33%.

In addition to this, Africa seems to be faced with the unpleasantly ironic situation that her citizens are now beginning to believe that selected goods produced locally are of an inferior quality and are prepared to pay premium prices for imported goods which may in fact be of poorer quality than the ones produced locally.

Notwithstanding Africa’s full support of globalisation initiatives, one way to address some of its negative impacts could be for the region’s individual consumers to begin to adopt a strategic approach to their sourcing practices.

A short-term price gain can sometimes lead to unintended long-term pain and “sectorial deindustrialization”. If the region’s consumers are “strategically” prepared to support local sectors, over time, prices will relatively decrease with volume increases, quality and productivity gains. As the developed world has proven, the longer-term benefits of strategic consumer sourcing are more important than the short-term price gains associated with relatively cheaper imports.

In short, paying slightly more for locally made and sourced goods in the short-term will not only lead to lower prices in the medium- to long-term, but could also boost productivity and product quality, accelerate industrialisation, support job creation and reduce poverty on the continent – all of which facilitate the fulfillment of the beyond aid agenda, United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals, African Union’s Agenda 2063.

Douglas Boateng, Africa’s first ever appointed Professor Extraordinaire for supply and value chain management (SBL UNISA), is an International Professional certified Chartered Director and an adjunct academic. Independently recognised as one of the vertical specific global strategic thinkers on industrialization, supply and value chain governance and development, he continues to play leading academic and industrial roles in sectorial reforms both in Africa, and around the world.