Prices of petrol and diesel shot up 347 percent and 338 percent respectively between 2010 and 2019, due to the cedi’s persistent depreciation, taxes and levies, according to a new study by the Institute for Energy Security (IES).

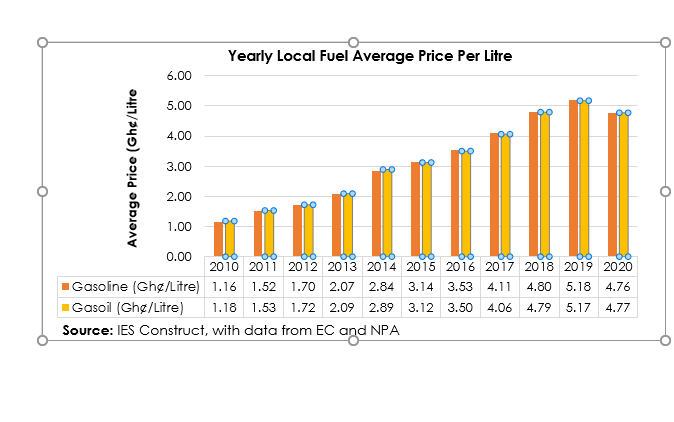

In 2010 the average pump price of petrol stood at GH¢1.16 per litre (GH¢5.22 a gallon), but in 2019 the average price was GH¢5.18 per litre (GH¢23.31 a gallon). Likewise, the average pump price of diesel moved from GH¢1.18 per litre (GH¢5.31 a gallon) in 2010 to GH¢5.17 per litre (GH¢23.27 a gallon) in 2019.

The analysis was carried out using data from the Energy Commission (EC), National Petroleum Authority (NPA) and IES MarketScan data, and revealed that by the end of 2019 domestic consumers of these products were paying more than four times the amount they parted with for a litre of fuel in 2010.

“Even as price deregulation and the falling prices of crude oil over the past decade offered a great opportunity for fuel consumers to spend less on the commodity, the poor performance of the cedi against major trading currencies, and the introduction of additional taxes/levies, eroded the benefits presented to consumers,” IES said.

Cedi’s depreciation

Over the period, the cedi depreciated approximately 265 percent – beginning at a yearly average of GH¢1.43 per US dollar in 2010 to a yearly average of GH¢5.22 per US dollar in 2019.

“Regardless of general reduction of crude oil prices over the decade, the cedi-depreciation, government fiscal policies among other factors significantly affect the price Ghanaians pay at present for finished products,” IES said.

Additionally, historical data from the Bank of Ghana (BoG) and US Energy Information Administration (EIA) show that performance of the cedi on the forex market greatly affects ex-pump prices Ghanaians pay more than crude oil prices does.

Meanwhile, had it not been for the global COVID-19 pandemic, it said, the price of domestic petrol that sold at GH¢5.30 per litre in early 2020 and is currently at GH¢5.10 per litre could have been more than GH¢6 per litre today.

The pandemic led to a slump in crude prices for a good part of 2020; hitting a 21-year low of US$16 per barrel in April, and trading at negative US$30-plus – the first time oil price has turned negative because of reduced global economic activity and markets’ lockdown due to the virus.

Furthermore, the period also saw the introduction of several taxes and levies – including the Price Stabilisation and Recovery Levy (PSRL), Road Fund Levy, Energy Fund Levy, Energy Debt Recovery Levy, and the Special Petroleum Tax (SPT). The margins cover the Primary Distribution Margin (PDM), BOST Margin, fuel marking margin, marketers margin, and the dealers (retailers/operators) margin, IES indicated.

The report added that: “But for some government fiscal policies which led to the introduction of new taxes and margins over the past five years, prices could have been much lower than we see at the pump today. The introduction of new taxes and levies, the upward adjustment in the RFL, the EDRL and the PSRL in 2019, plus the 100 percent increase of the BOST Margin, fundamentally aided in seeing pump prices go up”.

Consequently, year-on-year, the pump price of petrol went up averagely 18.4 percent within the period. The year 2014 recorded the highest year-on-year increase of 37 percent, with an average price of GH¢2.84 per litre as against GH¢2.07 per litre in 2013. Meanwhile, the least yearly increase of petrol pump price was recorded in 2019, as average price per litre increased from the previous rate of GH¢4.80 to GH¢5.18.

Before deregulation

Prior to full deregulation of the downstream petroleum sector in 2015, when consumer price for fuel was below the supply cost, government intervened through various forms of subsidisation because it had the exclusive right to do so through the NPA.

These interventions, IES noted, in a way distorted the market as it created perverse forms of incentives, resulting in unnecessarily high pump prices not reflective of international market conditions. However, the introduction of full deregulation has seen Oil Marketing Companies (OMCs) actively negotiating prices with Bulk Distribution Companies (BDCs) to benefit the final consumer.

“Domestic fuel prices were seeing sharp annual increases prior to price deregulation of 31 percent in 2011, 12 percent in 2012, 22 percent in 2013, and 37 percent in 2014,” IES stated.

Nevertheless, from 2015 onwards it said, the highest annual price rise recorded was in 2018 at 17 percent – with annual increases falling below 8 percent in 2019: “This literally means that introduction of the price deregulation regime in 2015 has greatly contributed to a slowdown in the margin of annual price increases over the last 5 years”.

Key indicators of local fuel prices

Key determinants of local fuel prices at the pump, the study says, include: global crude oil price, prices of finished products on the world market, the foreign exchange (forex) rate of the cedi to the US dollar, and the taxes and levies that are slapped on price per litre of domestic fuels.

The ex-pump price – the price the public buys fuel at the various filling stations – is a sum of ex-refinery price, export duty, taxes/levies, marketers and dealers’ margins.

The ex-refinery price constitutes the cost of product on the international market, insurance, freight, and other related charges.