Perhaps first among the many lessons of 2020 is that the notion of so‑called ‘black swan’ events is not some remote worry. These purportedly once‑in‑a‑generation events are occurring with increasing frequency.

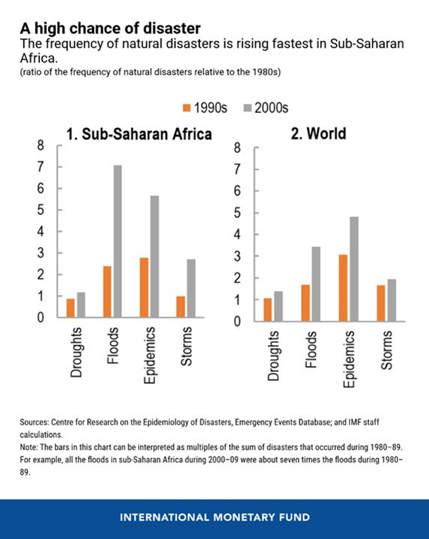

Take climate‑related shocks, especially in sub‑Saharan Africa. More than any other region, it is vulnerable to these events because of its heavy dependence on rain‑fed agriculture and its limited ability to adapt to shocks. Every year, the livelihoods of millions are threatened by climate‑induced disasters.

As we all continue to grapple with the COVID‑19 crisis, policymakers also need to look ahead. Countries need to ensure that the vast global fiscal support deployed to fight the pandemic also works to build a smarter, greener and more equitable future.

Nowhere is that more important than in sub‑Saharan Africa. It is where the needs are greatest and also home to the world’s youngest population, creating added urgency to act now to build forward better. Together, we need to chart a path to a more resilient recovery.

Why resilience matters

Our Regional Economic Outlook for sub-Saharan Africa published earlier this year highlights the lasting damage in the region from climate events. Over the medium term, annual per capita economic growth can decline an additional 1 percentage point with each drought. That impact is eight times worse than for an emerging market or developing economy in other parts of the world.

Nelson Mandela once said: “Do not judge me by my successes, judge me by how many times I fell down and got back up again”.

Given the increased frequency of shocks, building capacity to withstand them becomes essential to protect development gains.

Take investing in a smarter, digital economy; in another chapter of the Regional Economic Outlook we found that expanding Internet access in sub‑Saharan Africa by 10 percent of the population could increase real per capita GDP growth by as much as 4 percentage points.

In other words, a recovery that raises resilience will not just save lives, but also translate into higher living standards, better‑quality jobs, and more opportunity for all.

To achieve this, fiscal and financial policies need to prioritise investing in people, infrastructure, and coping mechanisms.

Empowering people

Investing in healthcare and education can pay large dividends in terms of growth, productivity, gender equity, and living standards. But investing in people is also critical for building resilience.

People who are physically resilient spend less on extra medical care; and if they do fall sick, they return to work or school sooner.

Of course, good health depends on good nutrition. When a climate shock hits, having access to enough safe and nutritious food is essential to survival. And this is where better education on the impact of climate change can help countries safeguard agricultural output. In Chad, for example, farmers are improving water retention through new rainwater harvesting techniques.

Access to new technologies can help farmers and doctors. Sierra Leone launched a new drone corridor last November, the first in West Africa, to monitor agricultural conditions and enable rapid delivery of medicine. Better mobile phone networks mean better access to early warning systems and weather information—even in the form of simple voice messages—that enable more productive and climate‑smart agriculture.

But investing in people is more than just finding better ways to do existing jobs. It is also about carving out new jobs. Better jobs. It is therefore vital to invest in building digital skills.

Our analysis shows that on average, digitally‑connected firms in the region employ eight times more workers, and create higher skilled, full‑time jobs. Also, increased Internet penetration is associated with a larger share of women working in the services sector—the shift to more employment in services is two and a half times larger for women than men.

Enhancing infrastructure

Good infrastructure is the backbone of any healthy and resilient economy. However, in a region where large‑scale infrastructure investments are already badly needed, there is an added premium on infrastructure investments that are smart, green and inclusive.

While the pandemic seems set to accelerate sub‑Saharan Africa’s digital transformation, this won’t happen by itself. It requires substantial investment in infrastructure—both digital‑friendly traditional infrastructure (including more reliable electricity) and digital‑ready information technology infrastructure.

Almost all countries in the region, except just a few, are connected through submarine cables or via cross‑border terrestrial links. But more needs to be done to improve digital access within countries and to reverse the widening gender gap.

At the same time, countries faced with the ravages of climate events need greater investment in weather‑resilient infrastructure. For instance, Mozambique’s Beira Port – a major regional trade and transportation hub – was operational within days of each of two consecutive cyclones, thanks to extensive drainage systems and well‑constructed buildings and roads.

Digital and climate-resilient infrastructure can go hand‑in‑hand. One‑fifth of sub‑Saharan Africa’s electricity is generated from hydropower – which is susceptible to droughts – so we need greater efforts to diversify electricity sources over the long run.

This means moving toward other renewable energy sources, such as solar and wind power. This shift will help reduce carbon emissions, spread electrification, and create jobs.

In Kenya, government increased access to electricity from 40 to 70 percent of the population in large part through the use of small, off‑grid, solar‑powered energy plants.

The added bonus is that the pay‑as‑you‑go, mobile money model makes this initiative accessible and easy to expand; plus, it created 10 times more jobs than in traditional utilities.

Strengthening coping mechanisms

Following a shock, social assistance and access to finance, among others, act as buffers that help people and businesses cope.

They compensate for lost income – allowing households to smooth consumption and buy essentials like food – and make it possible for businesses to continue operating.

A good example is Ethiopia’s Productive Safety Net Programme, which provides emergency cash transfers to food‑insecure households.

By requiring recipients to use bank accounts, the transfers are received quickly and financial inclusion has improved.

Broadening access to finance for low‑income households and small businesses helps them better cope during a shock.

It also makes it easier for households to empower themselves by investing in health, education and so on, and for businesses to invest in productive projects.

Where digitalisation supports better policy design and better economic outcomes, it can be a win‑win.

Governments are also taking advantage of the region’s leadership in mobile money to provide immediate support to households and businesses, while promoting social distancing. For instance, Togo’s ‘NOVISSI’ social protection programme uses mobile money and electronic cash transfers to support informal sector workers impacted by COVID‑19.

One thing is clear: achieving a resilient recovery in sub‑Saharan Africa, as elsewhere, will not be easy.

For one, it will be expensive. Precisely estimating the costs is not easy, given complementarities between investments in people, infrastructure and policies. But it will certainly be in the hundreds of billions of dollars over the coming years.

Meanwhile, of course, the COVID‑19 crisis is taking a toll on the region’s already limited fiscal space. And even before the crisis, most countries’ public debts were increasing rapidly.

Second, it will require transformative reforms. As important as external support is, it won’t be either effective or sufficient unless policy-induced distortions that stymie private investment are eliminated or public finance management systems improve.

More domestic revenue mobilisation will also be imperative – something which digitalisation can help by improving the efficiency of collection.

Third, support from the international community will be vital. Stepped‑up debt-relief, financing and capacity development will all be needed.

The IMF is supporting the recovery in sub‑Saharan Africa through all three of those channels, and we certainly will be doing more in the years ahead.

As we noted at the outset by invoking Nelson Mandela, getting back up after being knocked down is key.

The fact is investing in a more resilient future will be more cost‑effective than repeated rebuilding after crises or disasters.

That should be the measure of today’s success – encouraging a more virtuous cycle and more resilient development path for the region.