Strategic Sourcing and Industrialisation insights with Prof Douglas Boateng

Over the next 30 years, Sub-Saharan Africa is predicted to account for the majority share of the world’s population growth with the United Nations World Population Prospects forecasting that around two thirds of growth in the world’s population between 2020 and 2050 will take place in Africa.

Africa’s working age population is expected to double by 2050 while many other continents will see their working age population shrink as a result of aging populations. An African Development Bank report has also predicted that nearly 40 percent of the world’s working age population is expected to reside in Africa by 2100.

The predicted population growth has significant implications for industrialisation and socio-economic development in Africa. To date, the African continent has made great strides from colonial occupation and exploitation. However, investment, economic growth and development continue to remain focused on the extraction of resources.

This has left Africa’s growth and trade trajectories largely the same – still driven by raw materials and primary commodities including, oil, gas, metals and cash crops.

Similarly, due to the natural resource wealth in Africa, much of the region’s industrial production has remained largely centred on resource-based production with it counting for roughly half of the total manufacturing value-add and manufacturing exports. The situation is not different in Ghana, which according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) was one of world’s fastest growing economies in 2019.

Whilst there have been positive developments in a number of African countries some of these high growth rates must be viewed in context, as a number of these economies – mostly relatively small – are expanding from a very low base, making improvements seem disproportionately impressive.

Slow progress is better than no progress and yes, African is definitely rising. The big question is who is really benefiting from this economic growth which is in most cases do not translate into genuine long term and impactful economic development?

Investments in manufacturing also tend to be uneven with an African Growth Initiative report indicating that approximately 70 % of manufacturing activities on the continent are currently confined to few countries. They include amongst others, South Africa, Mauritius, Egypt and Morocco. In recent years countries, including Nigeria, Ethiopia, Kenya, Ghana, Rwanda and Tanzania, have registered growth rates in manufacturing of above or close to 10%, albeit from low bases.

According to the United Nations, over 80% of the region’s exports are shipped overseas – mostly to the European Union, China and the United States.

Data from one of the most recent UN Economic Development in Africa reports, revealed that between the period of 2015 and 2017 total trade from Africa to the rest of the world averaged US$760 billion. These figures suggest that Africa is industrialising other regions of the world at a faster pace than what is happening on the continent itself and reveals that Africa is not harnessing the collective value-chain resources at her disposal.

Well over three quarters of African exports are heavily focused on natural resources and raw materials to be converted into work in progress and finished goods and then re-exported back into the continent.

The non-oil sectors, including agriculture, manufacturing and services are certainly growing. However, the over dependence on extractive industries and export of cash crops such as cocoa, cashew nuts, rubber, coffee, oil palm; metals including gold, silver, platinum, bauxite, nickel, copper, lead and Zinc and oil means that not enough “value addition” jobs are being created to provide for the ever-expanding population.

Sustained upward regional growth depends on much needed intra-African trade, industralisation, institutional governance and economic diversification all of which can only be realised through collective national and regional effort, co-operation and innovative strategic sourcing practices. Despite all the internal resources at its disposal, the African continent is still home to some of the most unequal countries in the world.

With de-industrialisation and its proven negative impact on local and regional poverty reduction increasingly becoming a major concern across the continent, African governments, public and private sector organisations should be looking to renegotiate their potential value adding participation within vertical specific global supply chains to directly and indirectly boost local and regional wide economic development.

Unfortunately, at present, many public and private sector executives and policy makers generally continue to adopt a “mere suppliership” modus operandi when it comes to the acquisition and supply of tangible and intangible goods and services. As a result, they are more prone to opt for short-term cost and profit gains as opposed to medium- to long-term win-win collaborative value adding, job and wealth creating partnerships.

This mindset limits opportunities for the implementation of developmental driven procurement strategies.

The over one billion Africans (1187 billion) are collectively the largest group of people in the world that consume products generally not produced on their continent. The end result is that while the rest of the world is strategically sourcing from Africa to meet their medium- to long-term developmental needs, the majority of the African population and companies are buying from outside the continent to meet short- to medium-term needs.

In 2017 a Brookings report indicated that the share of intra-African exports as a percentage of total African exports sat at around 17 percent. A significantly low percentage when compared to the likes of Europe (69 percent), Asia (59 percent), and North America (31 percent). This is not sustainable.

Governments need to begin to prioritise industrialisation through innovative supply chain interventions that allow for focus on local value add to raw materials, job creation and economic development thereby moving the economy up the value chain, whilst at the same time leveraging aspects of procurement to stimulate strategic sourcing along the local supply channel to help reduce reliance on the importation of basic necessities.

As proven in other economies, this structural change will help to move labour from low productivity sectors to higher productivity employment, thereby leading to more sustainable local value addition and job opportunities – especially for the youth, people with disabilities and women.

Short term thinking is the enemy of long term success. The bottom line is that presently, African governments and companies generally buy products instead of strategically sourcing them. This short-term buying practice is widespread at the individual consumer level as well. In addition to exporting raw materials, Africa is also exporting money, and even skilled human capital, through these buying habits.

A fundamental paradigm shift in these buying attitudes and practices can, over time, lead to significant increases in the exchange of goods and services between various nations on the continent – enhancing intra-African trade and supporting regional economic development.

The COVID-19 pandemic has certainly given the region’s leaders and policy makers some serious food for thought. As the dynamics of global trade become ever-more complex, strategic industrial sourcing will become an increasingly important factor contributing towards the realisation of regional medium- to long-term growth industralisation and economic development

By adopting strategic sourcing, both public and private sector procuring organisations can begin to seriously move towards “local value chain developmental sourcing” and productivity improvements as opposed to just buying. With industralisation achieved through changing regional wide industrial and consumer sourcing patterns, African countries will ultimately and significantly be sourcing and consuming what they internally produce.

This internally generated demand will positively impact the region’s prosperity and the prospects of long-term job creation for current and future generations. The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) which came into effect in March 2018 will also have a significant role to play in opening up opportunities for strategic sourcing practices to become a continental reality.

The AfCFTA aims to provide a single market for goods and services focused on facilitating industralisation, supporting manufacturing, promoting economic diversification and sustainable growth and enabling jobs creation on the continent. In addition to a single continental market, AfCFTA will facilitate intra-African trade buy creating a customs union with free movement of capital and business travelers.

If the objectives of AfCFTA are achieved it is anticipated that Africa’s manufacturing sector will double in size, with annual output reaching $1 trillion by 2025. It is also expected that through increased local value add, economies of scale and sectorial productivity improvements will be achieved.

This is certainly positive news for the region in that if through supply chain thinking, the inputs required for production are strategically sourced for the various manufacturing requirements, it will undoubtedly generate demand for agriculture, mining, and other raw materials as well as for energy and information technologies, whilst concurrently increasing the supply of products for consumer markets, construction, and other sectors. Such value chain developmental thinking will have a direct and positive impact on much needed regional industralisation and job creation.

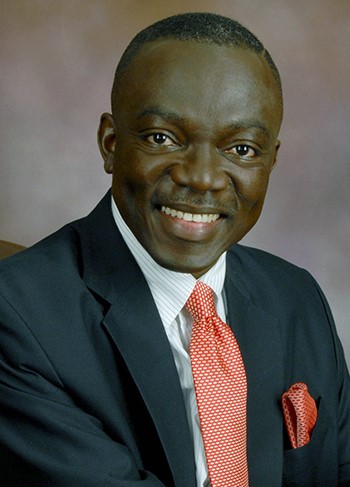

Douglas Boateng, Africa’s first ever appointed Professor Extraordinaire for supply and value chain management (SBL UNISA), is an International Professional certified Chartered Director and an adjunct academic. Independently recognised as one of the vertical specific global strategic thinkers on industrialization, supply and value chain governance and development, he continues to play leading academic and industrial roles in sectorial reforms both in Africa, and around the world.

He has received independent recognitions and numerous lifetime achievement awards for his extraordinary contribution to the academic and industrial advancement of supply chain management from various international organisations including the Chartered Institute of Procurement and Supply, the Commonwealth Business Council and American multi-national Hewlett Packard (HP). For more information visit www.douglasboateng.com and www.panavest.com