By Constance Kwame GBEDZO

It has become imperative to have a more vibrant SME banking regime to anchor Ghana’s developmental agenda, as assisting the growth of SMEs will benefit national economy as well.

Many SMEs in Ghana often rely on informal sources of capital, such as borrowing from relatives, to meet their financial needs. Indeed, SMEs need access to sustainable financial services in order to grow and impact the economy. However, there exists significant gap in SME access to finance.

SME Banks are set up to provide innovative financial solutions to SMEs in empowering them to achieve their full potential. Their target Market is SMEs in the commerce, agriculture, manufacturing, and services sectors.

These sectors are not fully catered for by the current universal banks as they consider them very volatile. This has created a gap that needs to be filled to boost economic growth.

By debunking misconceptions of SME banking, establishing its business case, and sharing global good practices, this paper hopes to support banks and government in building stronger, sounder services for small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in Ghana.

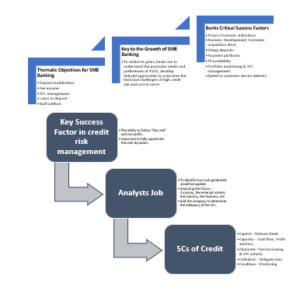

To the banks, serving SMEs can be profitable and rewarding. In order to serve the SME market profitably, banks need to follow a process for market entry that begins with understanding the specific opportunity in the SME sector, and end with developing a strategy and implementation plan.

There is need for market assessment and operational diagnostic. SME Banks need to develop Value Chain Industries in Agricultural Inputs, Food Processing, Logistics and Supply Chain Management, Healthcare Services, the Renewable Energy, for example.

Also, Government interventions are necessary to ensure survival of SMEs, especially in times of economic and financial crisis as being experienced in Ghana today. There is the need for government to look at the current capital requirements the commercial banks, especially for those that are to focus on SMEs financing. This paper is making a proposal of GHS 100 million to GHS 200 million for banks focusing mainly on SMEs financing.

The Banks and Specialized Deposit-Taking Institutions Act, 2016, Act 930 will need to be amended to support this from the current GHS400 million for all universal banks in Ghana. Although there are different policy perspectives on the relative merits of government intervention, banks and SMEs alike should be supportive of many such policies, particularly those that enable better risk management.

Creation and sustenance of SME Banks will open the economy of Ghana, and indeed, support Ghana’s industrialization programs and the 24-hour economic model.

The banking sector includes commercial and investment banks, leasing companies, microfinance institutions (MFIs), Savings and Loans Companies, and other related institutions. This paper pays particular attention to commercial banks, which are critically important financial intermediaries in Ghana, as they link savings and investments.

Commercial banks normally lend to, rather than invest in, SMEs. Unlike other specialized finance providers, commercial banks offer a broad suite of products and services including deposit, credit, transaction and advisory services. They also focus on enterprises in the formal sector, rather than informal micro enterprises which MFIs traditionally serve.

Composition of the Industry

Traditionally, the SME banking market is one served by small local banks that specialize in niche market segments. These banks employ a relationship-lending approach that relies on lenient information gathered through personal contact.

However, in response to perceived profitability, and competition in other banking segments, many larger banks including private and government-owned domestic banks, and foreign banks moved largely “downstream” in the direction of the SME segment.

Arguably, large banks are not primarily suited for relationship lending. However, they do have certain plusses in serving the SME sector. They often employ state-of-the-art business models, develop customized statistical credit scoring approaches, leverage connections with large multinationals to reach SME suppliers, and provide sophisticated and technology-based non-lending products at scale.

Large banks are, however, not the only new arrivals to the SME space. Successful MFIs have also looked “upstream” to serve SMEs. They serve SMEs by offering relatively large loans to the bottom of the SME market. They do so in much the same way as large banks initially made relatively small loans to the top of the SME market.

In Ghana, most MFIs and the local banks serving SMEs have not become formal financial institutions. They often lack financial and human capital and organizational missions that are required to attain sustainable business.

Ghana’s Recent Macro Economic Indicators

Over the years, Ghana has had worsening fiscal and balance of trade deficits, and had depended on the money market to finance its budget deficits. Provisional gross public debt at end Q1-2023 stood at GH₵569.35 billion (US$51.67 billion), representing 71.1 percent of GDP, a slight decrease of 20 basis points from 71.3 percent recorded at the end of Q4-2022.

This comprised external debt of GH₵322.56 billion (US$29.27 billion); 40.3 percent of GDP, and domestic debt of GH₵246.79 billion (US$22.4 billion); 30.8 percent of GDP. Government, since 2017, exploited the Eurobond Market for support, mostly to finance debt repayment, capital and heavily recurrent expenditures.

Domestic interest rates, however, were increased for Treasury Bills and Government Bonds. The Private Sector was being crowded out as commercial bank would rather lend to government as opposed to SMEs.

In 2020, when government started facing debts payment challenges, they began playing down on the short term government instruments, 1.e. treasury bills for the 2-3 year bonds. By 2022, the risk of debt distress had actually crystallized. Debt to GDP went as high as 92.69 percent in 2022. This has subsided to 71.3 percent by Q4-2022, and 71.1 percent Q1-2023. Fiscal deficit went as high as 15.8%.

Other Macro-economic factors comprising a major challenges in the operating environment include; overall macro-economic instability, high inflation gone as high as 54% in 2023, interest rates sky-rocketed to an average rate of 31.40 percent in October 2022 compared to 22.53% in May 2022 (i.e., high cost of capital to lend), and exchange rate averaged US$1.0/GHs10.20 in 2022 from US$1.0/GHs5.70 in 2019.

Ghana has been booted out of the Eurobond Market. Ghanaians were subjected to unprecedented domestic debt exchange program. Liquidity for both government and commercial banks was distressed.

Bank audited financial statements for 2022 reflected the entire impact of the Domestic Debt Exchange Programme (DDEP) by the end of March 2023. Most banks reported considerable losses due to mark-to-market valuation losses on their respective holdings of Government of Ghana bonds. Value of financial assets were devalued.

Bank of Ghana, the regulator, also recorded heavy loss of GHs60 billion cedis due high impairment provisions. An average of 40% of the earning assets of Commercial Banks were also held in government instruments. Per the IFRS-9 requirements, these assets were automatically impaired. This has distressed the liquidity for these banks, enterprises and consumers at large.

The ‘PRESS RELEASE: STATEMENT ON BANK OF GHANA’S 2022 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS’ on 9TH AUGUST 2023 explains it all. “Bank of Ghana released its full-year 2022 audited financial statements on 28th July 2023. The financial statements reported a total loss of GHS60 billion, which has since become a matter of unfortunate politicization.

It is noteworthy that GHS53.1 billion of those losses were a direct result of the Government’s domestic debt restructuring exercise (phase 1 and II). It is important to put the Bank of Ghana’s 2022 financial results in proper context with a clear statement of the problem that Ghana faced and the chronology of events in Ghana since 2019.

There was a clear mismatch between revenue inflows and expenditure financed in 2020 by exceptional support from the IMF and World Bank resources, and in addition to financing from the Bank of Ghana through the issuance of the GHS10 billion Covid-19 bond.

As a result, sovereign spreads on Ghana bonds widened, signaling investor dissatisfaction with the stance of fiscal policy. The Budget for 2022, which was read in 2021, failed to address fiscal concerns as the Budget was even more expansionary by about 23% with a raft of revenue measures to raise financing. As a result, the Credit Rating Agencies further downgraded Ghana’s sovereign debt rating, which blocked Ghana’s access to international capital market borrowing.

This triggered a liquidity crisis, spilling over into a balance of payments crisis. External and domestic payments needed to be made, the domestic auction was failing, and the Bank of Ghana had to step in to arrest a major economic and social crisis.

In 2 months, the Bank of Ghana lost US$500 million in reserves and built significant overdraft with the government as a result of the auction failures. It became clear that Ghana was on a path that was unsustainable, and the Government had to approach the IMF for support in July 2022.

The IMF process included putting into place a credible programme of reform, which included restructuring of the total government debt to sustainable levels. Until Staff Level Agreement with the IMF was reached in December 2022, the Bank of Ghana had to continue to provide the necessary support to keep the economy running.

In line with the provisions of the Bank of Ghana Act, (Act 612), as amended, the Bank informed the Minister of the developments in its finances. The Minister reported this to Parliament as part of his briefing to Parliament on the IMF programme and the Domestic Debt Exchange.

A major plank of the corrective action required for the IMF programme was the Domestic Debt Exchange, where the stock of Government of Ghana debt was to be halved from 105% of GDP to 55% of GDP by 2028.

The holders of Government debt had their debt instruments exchanged for new ones with lower interest payments and longer terms. Despite the losses inflicted on households and banks, the threshold of 55% of GDP was not met. The Bank of Ghana was used to close the gap to enable Ghana meet the debt threshold that qualified Ghana for the IMF programme (Bank of Ghana therefore, acted as a loss absorber).

This means the Bank of Ghana had to absorb a 50% haircut on its non- marketable holdings of Government debt instruments. This singular act led to significant impairment losses of GHS 32.3 billion to the Bank’s accounts. Impairments of marketable instruments also accounted for another GHS16.1 billion, bringing the total impairments of Government holdings to GHS48.4 billion.

As experienced by central banks globally, price and exchange rate movements led to a loss of GHS5.2 billion whiles impairments of COCOBOD loans amounted to GHS4.7 billion. This is the reason the Bank of Ghana reported a loss of GHS60 billion in 2022. Central banks are not commercial banks.

This financial outcome has very little implication for the operations of the Bank of Ghana as supported by evidence from other central banks. Technically, Central Banks cannot be insolvent or bankrupt. Bank of Ghana assures key stakeholders and the general public that we are committed to the highest standards of prudent management, governance, and transparent accounting and audit practices.”

Ghana had continued to depend on the money market at this point to finance recurrent expenditures. The resultant effects are that the SMEs have been crowded out. The banks are mainly interested in financing government instruments which prior to the debt exchange program, were considered risk-free.

Banks are not necessarily investing or lending to the private sector and are heavily investing in government instruments. Banks are discouraging lending to the private sector mainly to avoid NPLs.

The banks’ avoidance of the private sector lending is to mitigate the risk of default and increase in NPLs. Nonetheless, banks would naturally lend to the private sector at interest rates above that of government instruments in order to take care of the risk and avoiding the opportunity of ARBITRAGE.

Once again, this has naturally crowded out the private sector.

Financial Sector Crisis

The banking sector reforms date back in 2017, when the Bank of Ghana (BoG) embarked on a ‘comprehensive reform agenda’, with the objective of cleaning up the banking industry and strengthening the regulatory and supervisory framework for a more resilient banking sector.

The most significant component of the said banking sector reforms was the new minimum capital directive issued on 11 September 2017. The directive required universal banks operating in Ghana to increase their minimum stated capital to GHS400 million by the end of 2018. In effect, the number of banks has shrunk by eleven (11), representing a 32% decline from the 34 banks that operated as universal banks prior to the coming into effect of the new minimum capital directive.

The total number of banks currently operating as universal banks in Ghana stands at twenty-three (23). Out of the eleven (11) banks that exited the market following the issuance of the new minimum capital directive, three were assessed as insolvent by BoG and had their licenses revoked even before the deadline for compliance.

These are: UniBank Ghana Limited (UGL), Beige Bank (TBB), The Royal Bank Limited (TRB), Sovereign Bank Limited (SBL), Construction Bank Limited (TCB), Heritage Bank Limited (HBL), Premium Bank Ghana Limited (PBG), Bank of Baroda (BoB).

Sovereign Bank and Construction bank had their banking licences revoked for obtaining them by false pretenses through the use of suspicious and non-existent capital, according to the Bank of Ghana.

The remaining six have had to either exit the market or merge with other banks for various reasons, including those related to the new minimum capital requirement: Heritage Bank Limited (HBL) and Premium Bank Ghana Limited (PBG) had their licenses revoked.

The reasons provided by BoG for the revocation of their licenses were insolvency in the case of Premium bank and questionable source of capital for Heritage bank.

Bank of Baroda (BoB) “closed shop” and exited the market on their own volition also for reasons related to the new minimum capital requirement. BoG approved three mergers involving six banks, effectively accounting for three more exits. The approved mergers are: First National Bank & GHL Bank Limited, Energy Bank & First Atlantic Bank and Sahel-Sahara Bank & Omni Bank.

Several MFIs, Savings and Loans Companies and Asset Management Companies were also collapsed.

Consequently, SME banking suffered.

The SME Market

A common definition of SMEs includes registered businesses with less than 250 employees. This places the vast majority of all firms in the SME sector. To narrow this category, SMEs are sometimes distinguished from microenterprises as having a minimum number of employees, such as 5 or 10.

Alternative criteria for defining the sector includes annual sales, assets, and size of loan or investment. Many banks currently serving SMEs do in fact use annual sales figures, and average bank-reported maximum thresholds of $10 million.

To qualify as a micro, small, or medium enterprise (MSME) under the World Bank classification, a firm must meet two of three maximum requirements for employees, assets, or annual sales. They can be further divided into small enterprises (SEs) and medium enterprises (MEs).

SMEs are estimated to account for at least 95 percent of registered firms worldwide. In developing countries like Ghana, many SMEs operate in the informal sector, and although they are excluded from most accounts of the SME sector, they may represent a potential market for SME banking.

The SME banking sector is best defined conceptually by its position between large corporations and mostly-informal microenterprises. SMEs are firms whose financial requirements are too large for microfinance, but are too small to be effectively served by corporate banking models.

SME banking appears to be growing fast in Ghana.

Economic Potentials of SMEs

SMEs represent a large and economically important sector in Ghana. They are central to economic development in Ghana. They are active at every point in the value chain as producers, suppliers, distributors, retailers, and service providers, often in symbiotic relationships with larger businesses.

Studies have shown that women constitute approximately 46% of the entrepreneurial workforce in Ghana. This is an evidence to the significant strides women are making across various sectors in agriculture, tourism, healthcare, technology and education.

Regarding agriculture, women entrepreneurs are particularly active in food crop farming, not only as farmers but also innovators that are introducing sustainable farming techniques that are both eco-friendly and enhancing yield. Women entrepreneurs in Ghana are not just contributing to the economy, but are essential for economic growth and societal improvement.

A thriving SME sector is commonly considered a sign of a thriving economy as a whole. In the advanced countries, SMEs account for over half of national output.

Many SMEs in Ghana often rely on informal sources of capital, such as borrowing from relatives, to meet finance needs. There exists significant gap in SME access to finance, attributable to factors in the operating environment, such as regulation and macroeconomic conditions.

In order for SMEs to grow and their positive impact on the economy to continue, they need access to financial services, which has historically been severely constrained. However, when a small or medium enterprise does access formal channels, it looks to a bank as its primary source of financial services.

SME banking industry is young and growing. In Ghana, ‘we need to envision to create sustainable jobs for Ghanaians through the transformation of Ghana into an import substitution and export-led economy, among others.

The mechanisms available to achieve this should include; modernizing and mechanizing agriculture, promoting agro-processing and manufacturing, tourism, promoting entrepreneurship, and generally providing incentives for the private sector to thrive.’ There is the need for a vibrant SME banking regime to anchor Ghana’s developmental agenda.

SME Banking in Ghana

SME market includes a wide range of firms and sizes. SMEs are often family owned, and in most cases, the owner is the primary financial decision maker. The development of a commercial banking sector in Ghana began with addressing the needs of large corporate clients.

This model has historically consisted of managing very high-value transactions for a small number of low-risk clients. Outside of the commercial banking sector, MFIs arose to offer working capital loans to microenterprises, typically ranging from median amounts of GHs15,000.00 in Ghana.

SME finance has been referred to as the “missing middle” because SME financial requirements are too great for most MFIs and SMEs have been viewed as too small, risky, or costly for traditional commercial banks.

SMEs serve as a middle ground for the economy, often transacting with large corporations and providing links to the formal sector for micro-entrepreneurs. SMEs do operate in different ways compared to large enterprises (LEs), and may be less sophisticated financially, lacking in business planning and cash flow management expertise.

More banks are developing strategies and creating SME units. Commercial Banks have developed synergies with their existing bank operations, by integrating the service of SMEs with that of the personal banking of the owner through retail or private banking portfolios.

The potential profitability of serving SMEs has been enhanced by the development of new business models to engage small enterprises. SME banking operations currently have deployed sophisticated high-volume approaches.

Government also recognizes the importance of the SME sector and are working to support its access to finance. Recently, government secured funding from the World Bank/IMF/IFC, Mastercard Foundation, and many other donors to support SME growth. There is the need for deliberate government policies towards addressing legal and regulatory barriers, building credit infrastructure and seeking donor support.

SME Banking, an Industry in Transition

As stated earlier, SMEs fall between two markets where there is a finance gap commonly described as the “missing middle”. SMEs in Ghana have historically lacked access to financial products and services. MFIs have emerged to serve the smallest of these enterprises, while banking institutions have typically concentrated on large corporations.

However, in recent years, this is beginning to change. SME banking, as an industry, is growing. Banks are now demonstrating that the SME segment can be served profitably provided it is properly understood. From a market that was considered too difficult to serve, it has now become a strategic target of banks.

Competition in the banking industry is contributing to commercial banks moving “downstream” to serve SMEs. For these banks, unmet SME demand for financial services has become an indicator of opportunity to expand their market share and increase profit. Many banks perceive significant opportunities in the SME sector. Rather than overlooking or avoiding the market, banks have begun to target SMEs as a profitable segment. The gap in financial services provided to SMEs, is shrinking.

Most of these large multinationals recorded huge loan defaults. Some successful MFIs also went “upstream” to serve SMEs. For certain MFIs, the ascent to SME banking has been facilitated by a relaxation of regulatory restrictions on loan size and maturity. They serve SMEs by offering relatively large loans to the bottom of the SME market.

The Bank of Ghana licensed some MFIs in the mid-2000s to enable them offer large loans to the SMEs. Others have converted into regulated banks in order to serve the market. These banks also folded up by 2017.

Unmet Demand for Banking Services

Despite the socio-economic importance of the SME sector, SMEs continue to be undersupplied with the financial products and services that are critical to their growth. There are two main obstacles to access to funding; cost of finance to growth and access to finance. These constraints are more acute particularly in Ghana. Not only do small firms have more difficulty accessing finance, but they are more negatively affected by this difficulty than larger firms.

Negative growth impact of financial constraints on small firms is two-thirds greater than the negative impact of financial constraints on large firms. Banks have begun to turn their attention toward this untapped market and their service of SMEs is a major factor in increasing SME access to finance. Although banks have previously focused on high-value, low-risk corporate clients, undeniably the SME market can be a profitable segment to banks.

By employing a range of measures, such as risk-adjusted pricing, credit scoring models, and SME-tailored non-lending products, banks are developing ways to mitigate risks, lower costs, and increase the overall benefit accrued from SME banking.

Few banks are using statistical inputs in credit risk assessment, and cost- effectively providing non-lending products at scale. Risk-adjusted pricing models have also been important tools enabling banks to profitably serve SMEs.

SMEs are particularly in need of bank services due to the following:

- Lack of cash flow to make large investments,

- Lack of access to capital markets as large firms can, and they often lack qualified staff to perform financial functions.

- Banks provided long-term debt can enable SMEs to invest in expansion without losing ownership. In addition, short-term and working capital loans help SMEs grow incrementally.

- Lastly, bank deposit and transaction products can improve operational efficiency and enable SMEs to outsource financial functions.

Capacity of SMEs in Obtaining Required Loans

SMEs may have difficulty obtaining these types of loans because of

- Inadequate financial records or assets to use as collateral.

- While some banks offer unsecured loans to SMEs, based on cash flow rather than collateral, these loans often come with shorter maturities; in general, collateral requirements have been the norm. Long-term finance is one of the most commonly cited needs of SMEs, and in many aspects, long-term loans are where the “missing middle” problem has been most acute in Ghana.

- The SME market has been perceived in the past by banks as risky, costly, and difficult to serve.

However, banks are finding effective solutions to challenges such as determining credit risk, lowering operating costs, and are profitably serving the SME sector.

Significance of Banking Interventions

Long-term financing products, such as term loans with longer maturities and fewer restrictions on usage, provide SMEs with investment capital for strategic business expansion. For example;

- Through research and development, or property and equipment purchases.

- Bank products can also enable SMEs to take on more and larger contracts. A small or medium enterprise may have a potential order from a customer in place, but need cash up front to complete the order.

- Banks can provide short-term working capital to such SMEs to purchase supplies, pay employees, and meet obligations to clients.

- Providing help with order fulfillment can extend across borders as well, with trade financing assistance. For example, with a letter of credit, exporting SMEs can offer customers better payment terms because a bank pays the enterprise based on documentation of the sale and extends credit to the customer of the enterprise.

- Other Products

SMEs have important operational needs that banks can meet with non-lending products. This includes; deposits and savings, transactional products, and advisory services. Some of these products can effectively enable SMEs to outsource financial functions to the bank.

- Deposit and savings products; Deposit and savings products provide businesses with basic financial management tools to help organize revenues and savings. Additionally, mutual funds and other investment products provide businesses with opportunities to obtain earnings on excess capital.

- Transactional products; Transactional products facilitate SME access to and use of available cash. Automatic payroll and payment collection, debit cards, and currency exchange are transactional bank offerings that lower the cost of doing business and streamline potentially complicated processes.

- Advisory products; SMEs can benefit from help in producing reliable financial statements, developing business plans, and selecting appropriate financing products. These advisory services can improve SME access to finance by enhancing its capacity to apply for credit.

SME Banking Challenges and the Operating Environment

Challenges to SME banking in the operating environment are as follows:

- Regulatory obstacles,

- Weak legal frameworks

- Macroeconomic factors

- Credit Information Asymmetry

- Risk Perception of SMEs

Regulatory Obstacles

On the supply side, these obstacles can directly reduce the profitability of SME banking by making it difficult to charge market rates or to recover nonperforming loans. Often, government measures intended to support SMEs may in fact have the opposite effect.

For example, interest rate ceilings, a policy that is intended to make lending more affordable for SMEs, can actually discourage competitive and commercial pricing and reduce the supply of credit.

On the demand side, regulatory obstacles can impact the willingness or ability of SMEs to borrow. SMEs that cannot navigate complex regulatory hurdles to formalization may choose to remain informal, and as a result, may not be bankable. Similarly, mandating audited financial statements may prevent SMEs from even applying for loans.

Weak Legal Frameworks

For example, ineffective contract enforcement, can deter banks from serving SMEs. A lending portfolio is in essence a range of contracts of varying dimensions. If weaknesses in the legal and judicial system make it difficult to enforce these contracts, this will increase the transaction cost of lending which will in turn make the smaller loans required by SMEs less attractive to banks.

It is important to note that the finance gap between SMEs and large firms appears greater in countries with worse protection of creditors and less effective judicial systems.

Legal frameworks also impact on the demand side; SMEs that lack effective and enforceable rights to their own assets may not be able to secure sufficient collateral to qualify for a bank loan.

Macro-economic Factors

Government of Ghana has experienced challenging macro-economic instabilities from 2021 to 2024, resulting from excessive borrowing mainly for consumption debt servicing and capital expenditure.

The situation got worsened when government eventually defaulted with debt distress on hand. This has had enormous effects on SME banking whose investments were also a subject of debt exchange program.

Other Macro-economic factors comprising a major challenges in the operating environment include; overall instability, high inflation, high interest rates (i.e., high cost of capital to lend), and exchange rate risk. The impact of the last of these has been illustrated in the current financial crisis.

Banks that have borrowed from international lenders in foreign currency, such as US dollars, have increase in the value of their outstanding local- currency-denominated loans and net worth drop when the dollar strengthened against the cedi. These factors have impacted all banking operations, especially the service of SMEs.

On the demand side, SMEs are more vulnerable to economic shocks.

Credit Information Infrastructure

Where reliable financial statements are lacking, the information on prospective SME borrowers provided by credit bureaus and collateral registries can be instrumental in banks’ abilities to sanction loans. SMEs find it more difficult to obtain loans in countries where this information is lacking.

Risk Perception of SMEs

This perception still constitutes significant stereotype against SMEs in Ghana. Commercial banks have traditionally viewed SMEs as a challenge because of information asymmetry, lack of collateral, and the higher cost of serving smaller transactions.

These three sets of challenges contributed to the “missing middle” financing gap in Ghana. These challenges may impact SME banking on the supply side by hampering effective banking operations, or on the demand side by inhibiting SMEs. However, as corporate banking margins continue to shrink and increasing fiscal restraint lowers yields on government borrowings, banks have begun to explore the SME space.

Rather than avoid risk, banks are now finding ways to incorporate the risks of serving SMEs into their pricing of financial products. Banks should be able to use risk calculations to develop multiple pricing approaches within the SME segment. SMEs should also have willingness to pay these risk-adjusted prices because they value the services being provided and because alternative providers are often more costly.

Some banks have been able to successfully serve this new and untapped market. If the banks develop strategies with focus on the SME sector and apply new banking models, banks may be reporting income growth rates and returns on assets in SME banking that exceed those of their overall banking operations.

Bank Approaches to the Challenges of Serving SMEs

Step-by-step SME/Business Banking strategy

- Synergize the corporate banking customer analysis with their suppliers and off-takers.

- Develop deeper understanding of the SME/Commercial banking market.

- Conduct an industry survey.

- Identify risk mitigants and Industry key success factors.

- Develop target list of customers.

- Perform need assessment.

- Develop commercial banking products i.e.

- Short term loans.

- Long term loans.

- Trade finance.

- Non lending products; Deposit and investment products, Salary payments, On-time payment platforms, Advisory services, etc.

- Acquire and screen customers.

- Identify sectors that drive the economy of Ghana

- Target customers.

- Set the risk acceptance criteria.

- Set product limits and Obligation for limits.

- Determine cost-effective ways of acquiring the customers.

- Begin with the existing customers.

- Proceed with the external customers.

- Serve customers:

- Meet the needs of existing customers.

- Build a growing diversities in portfolio.

- Determine profitable and unprofitable customers

- Manage information and knowledge.

- Model and manage risks using data.

- Use current data to adapt service approaches.

Other essentials: Risk management; Credit risk, Operational risk, liquidity risk, etc. and Sales culture.

In serving SME clients, Financial Institutions must develop capacity to predict risk without completely reliable financial information, by using tools such as credit scoring, has enabled banks to more effectively screen potential clients.

Banks need to improve efficiency by using mass-market approaches for smaller enterprises and using direct delivery channels where appropriate. Banks must also build their revenue base by prioritizing cross selling to existing clients.

Finally, banks need to adapt IT and MIS tools, and build capacity to effectively use these tools for managing information and knowledge in their service of the SME market, especially in understanding profitability and risk. Some of these innovations include multi-level service segmentation and creative involvement in equity financing of SMEs.

FIs, especially banks looking to enter the SME market or expand their SME operations should draw from the lessons of other banks’ experience in the following strategic areas:

- Strategy, SME focus and execution capabilities;

- Market segmentation, products and services;

- Sales culture and delivery channels;

- Credit risk management; and

- IT and MIS.

In view of Ghana’s developmental challenges, SME Banks need to develop the following Value Chain Industries:

- Agricultural Inputs: SME Bank can create a value chain industry for agricultural inputs, such as fertilizers, seeds, and pesticides.

- Food Processing: The bank can develop a value chain industry for food processing, enabling SMEs to process and package agricultural products for local and international markets.

- Logistics and Supply Chain Management: SME Banks can create a value chain industry for logistics, transportation and supply chain management, enabling SMEs to provide logistics and supply chain management services to businesses in Ghana and beyond.

- Healthcare Services: The bank can develop a value chain industry for healthcare services, enabling SMEs to provide medical services, including diagnostics, treatment, and prevention.

- Renewable Energy: Catalyst SME Bank can create a value chain industry for renewable energy, enabling SMEs to develop and launch new renewable energy projects, including solar, wind, and hydro power.

Financial institutions’ Capacity

To begin serving SMEs, MFIs often start with micro entrepreneur “graduates”, namely clients who began as individual micro borrowers who have grown in sophistication and size to qualify as small enterprises. For certain MFIs, the ascent to SME banking has been facilitated by a relaxation of regulatory restrictions on loan size and maturity. The Bank of Ghana also converted some MFIs into regulated banks in order to serve the market.

Government Support for SME Finance

Recognizing the importance of the SME sector, governments need to undertake a variety of measures to support SME access to finance in promoting development programs. These measures include;

- Reforming existing legal/regulatory barriers and reducing capital requirements for SME portfolios, perhaps by providing exceptions to international regulations designed with large loans in mind. The Banks and Specialized Deposit-Taking Institutions Act, 2016, Act 930 needs to be amended to support this from the current GHS400 million for all universal banks in Ghana.

- Taking actions to develop the SME finance market broadly, and Intervening in the market directly to jumpstart or incentivize lending to SMEs.

- Streamlining accounting requirements or formalization processes for SMEs.

- Governments may also take action to support SME access to finance by providing public goods and services targeted at incomplete markets and market failures. This can be helpful, particularly in countries where transparent information is difficult to obtain.

- Governments may also provide training to SMEs in financial statement preparation, business management skills, etc.

- On the supply side, governments need to build or support or improve the credit information infrastructure of the country, including credit bureaus and collateral registries. This is considered potentially important role for any government.

- Direct government intervention in the banking market. Such interventions can include direct lending through government-owned institutions and directed credit programs, where the government provides capital to banks specifically for lending to SMEs. The inspiration for these interventions is necessary where banks had not previously been interested in SMEs. As banks are targeting SMEs as a profitable sector, these government interventions may risk distorting the market and generating unintended consequences. Providing loan guarantees, where the government shares a portion of the credit risk on SME loans, have become a very common intervention.

SME Banking During a Global Economic Crisis

The world had experienced three (3) major crisis in recent time; the 2008 economic meltdown, Ghana’s Financial Sector Crisis in 2017, the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, and the Russia – Ukraine conflict and Ghana’s economic crisis 2022/24.

SMEs have been the first ones to be hit. SME banking has not been immune to the effects of the recent global financial crisis. Working capital is a critical need of SMEs during the crisis.

In response to this need, many governments have worked to support lending to SMEs, mostly through credit guarantees, provision of grant schemes, etc. However, government policies must not impair fair competition. Banks interviewed in Ghana, even in the midst of the crisis, report seeing SMEs as the economic future of their countries and express their desire to be positioned accordingly.

Today, despite the significant challenges posed by the current global economic crisis due to COVID and Russia-Ukraine War, and the uncertainty ahead, many banks seem to be holding fast to their strong commitment to the SME sector in Ghana.

Conclusion

Ghana needs to pay attention to creation of SME Banks as this will open the economy as these new banks will require, rented buildings for their offices, health care for their staff, telecommunication services for their networks, catering services for staff, cleaning services and a lot more other economic boosting appendages.

To effectively serve SMEs, banks need to change the way they do business, and manage risk, at each stage of the banking value chain. This begins with

- Working to understand the market, and how it differs from both the retail and commercial segments.

- Developing products and services; banks are beginning to understand that SME banking means much more than SME lending and are, therefore, prioritizing non-lending products in order to provide total customer value. The fact is that 60 percent of SME revenues could come from noncredit products.

- Finding ways to manage both costs and credit risk as they acquire and screen clients.

- A bank’s current portfolio provides both a low-cost starting point for generating new business and a source of valuable data that can enable it to understand and predict the risks associated with SME clients.

Appendixes

The Author is the CEO/Founder, Commodities Investments Ghana Ltd)

Expertise: Corporate Governance, Enterprise /Business Development, SME Trainer, Coach/Mentor and Pitch Expert