By Prince NKETIA

The foundation of the patent system is grounded on quid pro quo. The state grants exclusive exploitation of an invention to the inventor for 20 years. In return, the inventor discloses the best mode to practice the invention so that a person skilled in the art can practice same.

The disclosure serves as a guide for third parties to practice the invention after the expiration of the patent period. This system has stood the test of time.

The emergence of COVID-19 has however exposed some fundamental weaknesses in the entire patent architecture. Although COVID-19 vaccine manufacturers did disclose the best mode to manufacture their vaccines as the law requires, third-party vaccine manufacturers are unable to manufacture same.

The inability has exposed limitations in the disclosure requirement that defeat the very foundation of the Patent System. This means that innovators of COVID-19 vaccines enjoy the protection the state offers through patents.

However, their disclosure is not up to the standard required to permit third parties to manufacture the vaccines. This article addresses the weakness in the disclosure requirement and ways to remedy it.

A patent is a legal document granting its holder the exclusive right to control the use of an invention, as defined in the patent’s claims, within a limited geographical area and time by stopping others from, among other things, making, using or selling the invention without authorization. The patent system operates on the concept of quid pro quo. Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines quid pro quo as “something given or received for something else”.

An arrangement where something is given out to receive another thing in return. The state guarantees exclusive exploitation of an invention by its owner as an incentive to motivate inventors to invest in Research and Development (R&D) to come up with new inventions.

In exchange for exclusive exploitation, the inventor discloses publicly how the invention can be practiced in a codified manner. Binnie J explained that Patent protection rests on the concept of a bargain between the inventor and the public. In return for disclosure of the invention to the public, the inventor acquires for a limited time the exclusive right to exploit it.

The entire patent system is grounded on this quid pro quo arrangement between the patentee (inventor) and the state where the state guarantees exclusive right over the invention and the patentee ostensibly discloses the best mode to practice the invention. This creates a win-win situation for both parties.

Over the years, this arrangement between inventors and the state has functioned perfectly well. Once patent protection is granted, the patent lasts for at least 20 years from the date of the patent application. Within the years of protection, it is only the patentee or someone authorized by him who can practice the invention. Monopolies created by patents benefit both the public and the patentees. Each party ought to perform its part of the bargain to the satisfaction of the other.

The patent system precludes others from making, using, or selling an invention without permission from the inventor. It is only the patentee who can authorize another party to practice the invention under agreed terms. A patent, therefore, grants only a negative right (i.e., the right to exclude others).

According to US/Australian Economist Fritz Machlup, a patent confers the right to secure enforcement power of the state in excluding unauthorized persons for a specified number of years from making commercial use of a clearly identified invention.

There are a myriad of advantages available to a patentee. During the 20 years of exclusivity, the patentee can recoup the investment made in R&D; the patentee may grant licenses to others to practice the invention, the patentee may enter into a technology transfer agreement with other parties and the patentee has the right to determine the price of the invention among other things.

The overall economic aims of patent protection as originally summarized by Fritz Machlup are, to recognize the intellectual property rights of the inventor, to reward the inventor for his useful services to society, to give incentives to the inventor and the industry to invent, invest, innovate, and to provide incentives for early disclosure and dissemination of technical knowledge. These benefits attached to the patent system encourage organizations and States to sponsor R&D into breakthrough discoveries.

The State on the other hand benefits from the public disclosure done by the patentee. The disclosure permits third parties to practice the invention once the patent expires. During the pendency of the patent, the innovator determines the price at which the product is to be sold which is always exorbitant.

When the patent expires third parties are able to manufacture generic versions of the inventions at a reduced price. The innovator is forced to reduce its prices once competitors start producing the invention at a reduced price. The public benefits from this arrangement because of the reduction in price brought about by competition. Again, public access to technical information about the inventions serves as a launch pad to stimulate more innovations.

If the patentee were able to obtain a product monopoly without disclosing how to make the product, the public would get nothing in return for the grant of the monopoly. Furthermore, it has the potential to stifle creativity and innovation. This means that the disclosure requirement is pivotal to the grant of a patent.

The unfair distribution of COVID-19 vaccines especially in Low and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) has created a huge inequality gap. This is largely blamed on some imperfection in the patent system.

In as much as the innovators have disclosed the procedure for the manufacture of their vaccines as required of them, third parties are not able to manufacture same. Although third parties are precluded from manufacturing a vaccine with patent protection without authorization, exceptions created for products that are of public health importance permit third-party manufacturers in third-world countries to do that.

The Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights Agreement (TRIPS Agreement) has granted exceptions to the strict application of the 20-year exclusivity right to third-world countries under some circumstances. The challenge with the COVID-19 vaccine manufacture is that the disclosure made by the innovators meets the requirements of the law. However, the disclosure does not provide sufficient technical knowledge to permit third-party manufacturers to synthesize same.

This paper discusses the foundation upon which the patent system is built. It also delves into the subject of patentability and its eligibility requirements. The disclosure requirement which has become the chief cornerstone of patentability is explored.

Again, the strategies put in place to circumvent the protection patent offers under emergencies are discussed to its logical conclusion. Despite the strategies activated during emergencies, COVID-19 vaccine manufacture has eluded third parties and the reasons for this failure are revealed in this paper together with measures to address this challenge.

Patentability

TRIPS Agreement provides a minimum standards agreement, which allows member-states of the World Trade Organization to provide more extensive protection of intellectual property rights. Members are left free to determine the appropriate method of implementing the provisions of the Agreement within their legal systems and practice. Some aspects of Ghana’s Patent Act, 2003 (Act 657) were modeled after the provisions in the TRIPS Agreement. The Agreement provides standards for the various aspects of intellectual property rights enforcement and dispute resolution mechanisms.

Under the TRIPS Agreement, an invention qualifies for patent protection if it is new (novelty), has an inventive step (non-obviousness), and has industrial applicability (usefulness). Ghana’s Patent Act states that an invention is patentable if it is new, involves an inventive step and is industrially applicable. Subject Matter of patents under the TRIPS Agreement is provided as follows:

- Subject to the provisions of paragraphs 2 and 3, patents shall be available for any inventions, whether products or processes, in all fields of technology, provided that they are new, involve an inventive step, and are capable of industrial application.

From the foregoing, an invention qualifies for patent where it is not excluded from patentability and satisfies the eligibility requirements of novelty, inventive, and having industrial applicability.

Some inventions are excluded from the grant of patents even though they meet the eligibility requirement. The first hurdle to cross is to ascertain that the invention is not excluded from patentability. Having crossed this hurdle the next step is to assess the invention in accordance with the eligibility requirement.

Exclusion from patentability

The TRIPS Agreement states that inventions

“exploitation of which is necessary to protect ordre public or morality, including to protect human, animal or plant life or health or to avoid serious prejudice to the environment, provided that such exclusion is not made merely because the exploitation is prohibited by their law”.

TRIPS Agreement again provides that:

Members may also be excluded from patentability:

| (a) | diagnostic, therapeutic, and surgical methods for the treatment of humans or animals; | |||

| (b) | plants and animals other than micro-organisms, and essentially biological processes for the production of plants or animals other than non-biological and microbiological processes. However, Members shall provide for the protection of plant varieties either by patents by an effective sui generis system or by any combination thereof. The provisions of this subparagraph shall be reviewed four years after the date of entry into force of the WTO Agreement. |

For an invention to be patentable, it must first be considered as one that is not excluded from patentability. Section 2 of Patent Act 2003 (Act 657)-Ghana provides a list of matter excluded from Patent protection among which are the list stated in the TRIPS Agreement above. Once an invention is excluded from patent protection then that’s the end of the road as far as patent protection is concerned.

Newness/novelty

Ghana’s Patent Act provides that an invention is new if it is not anticipated by prior art. Prior art is defined as everything disclosed to the public anywhere in the world. In other words, prior art is any information on an invention that is publicly known. Lord Wedsbury espoused as follows: “The antecedent statement must be such that a person of ordinary knowledge of the subject would at once perceive, understand, and be able to practically to apply the discovery without the necessity of making further experiments and gaining further information before the invention can be made useful. If something remains to be ascertained which is necessary for the useful application of the discovery,that affords sufficient room for another valid patent”.

Lord Hoffman further stated as follows: “If I may summarise the effect of these two well-known statements, the matter relied upon as prior art must disclose subject matter which, if performed, would necessarily result in an infringement of the patent. That may be because the prior art discloses the same invention.

In that case there will be no question that performance of the earlier invention would infringe and usually it will be apparent to someone who is aware of both the prior art and the patent that it will do so. But patent infringement does not require that one should be aware that one is infringing: “whether or not a person is working lan]… invention is an objective fact independent of what he knows or thinks about what he is doing”: Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals Inc Vrs H N Norton & Co Ltd [1996] RPC 76, 90.

It follows that, whether or not it would be apparent to anyone at the time, whenever subject-matter described in the prior disclosure is capable of being performed and is -10- such that, if performed, it must result in the patent being infringed, the disclosure condition is satisfied. The flag has been planted, even though the author or maker of the prior art was not aware that he was doing so”.

Test for novelty

The test for novelty is hinged on two key concepts. These are priority dates and enablement.

Priority date

The priority date of a patent is the date on which the applicant first files a patent application in respect of his invention. This is referred to as the priority date of the patent because it enables him to invoke priority or a priority right. The priority date must be distinguished from the Filing Date. After securing your patent in country A under the Priority Date, you may wish to protect your invention in other countries by filing a patent within a year. The filing date is the date on which you filed your further application in the other countries. An applicant who has filed a first patent application for an invention has for filing another patent for that invention, a right of priority for a period of 12 months after the first filing. The priority right is enshrined in the Paris Convention.

(1) Any person who has duly filed an application for a patent, or for the registration of a utility model, or of an industrial design, or of a trademark, in one of the countries of the Union, or his successor in title, shall enjoy, for the purpose of filing in the other countries, a right of priority during the periods hereinafter fixed.

(2) Any filing that is equivalent to a regular national filing under the domestic legislation of any country of the Union or under bilateral or mutilateral treaties concluded between countries of the Union shall be recognized as giving rise to the right of priority.

(3) By a regular national filing is meant any filing that is adequate to establish the date on which the application was filed in the country concerned, whatever may be the subsequent fate of the application.

Enablement

Enablement is the second element in determining whether or not a particular invention was anticipated by prior art. This relates to whether the disclosure of the prior art was such that a person of ordinary skills in the art (PHOSITA) could carry it into effect without much struggle.

According to Lord Hoffman “enablement means that the ordinary skilled person would have been able to perform the invention which satisfies the requirement of disclosure. This requirement applies whether the disclosure is in matter which forms part of the state of the art by virtue of section 2(2) or, as in this case, section 2(3). The latter point was settled by the decision of this House in Asahi Kasei Kogyo KK’s Application [1991] RPC 485”.

Inventive step

The next requirement is the involvement of an inventive step. An invention is considered as having an inventive step if having regard to the prior art relevant to the application it would not have been obvious to a person having ordinary skill in the art. Article 56 of the European Patent Convention (EPC) is in pari materia with the provision under the Ghanaian Patent Act above and states that: “An invention shall be considered as involving an inventive step if, having regard to the state of the art, it is not obvious to a person skilled in the art. …”

The United States Supreme Court held that. “this patent simply arranges old elements with each performing the same function it had been known to perform, although perhaps producing a more striking result than in previous combinations. Such combinations are not patentable under standards appropriate for a combination patent”.

A US Court held that if a patent only improves an old device by substituting materials better suited to the purpose of the device, it will not be held valid. Where the inventive step is lacking as in the above scenarios, the grant of patent must fail because the invention fails to satisfy the key eligibility requirement of the inventive step.

The test for inventive step

Two of the most common steps to determine inventive step is the problem-and-solution approach under the European Patent Office and the Pozzoli test.

Problem and solution approach

In order to assess inventive step in an objective and predictable manner, the so called Problem-and-solution approach of the European Patent Office (EPO) is applied:

- Determining the ‘closest prior art’.

- Establishing the ‘objective technical problem’ to be solved, and

- Considering whether or not the claimed invention, starting from the closest prior art and the objective technical problem, would have been obvious to the skilled person.

In practice, the closest prior art is generally that which corresponds to a similar use and requires the minimum of structural and functional modifications to arrive at the claimed invention. According to the European Patent Office, the closest prior art must be assessed from the skilled person’s point of view on the day before the filing or priority date valid for the claimed invention.

In the second stage, one establishes objectively the technical problem to be solved. To do this one studies the application (or patent), the closest prior art and the difference (also called distinguishing features of the claimed invention in terms of features (structural or functional) between the claimed invention and the closest prior art identifies the technical effect resulting from the distinguishing features, and then formulates the technical effect resulting from the distinguishing features, and then formulates the technical problem. See European Patent Convention

In the third stage, the question to be answered is whether there is any teaching in the prior art as a whole that would have prompted the skilled person, faced with the objective technical problem, to modify or adapt the closest prior art while taking account of that teaching, thereby arriving at something falling within the terms of the claims, and thus achieving what the invention achieves.

Pozzoli test for inventive step

Pozzoli test for inventive step as follows:

- Step 1: Identify the person skilled in the art and their relevant common general knowledge (CGK).

- Step 2: Identify the inventive concept of the claim in question or if that cannot readily be done, construe it.

- Step 3: Identify what, if any, differences exist between the matter cited as forming part of the “state of the art” and the inventive concept.

- Step 4: Viewed without any knowledge of the alleged invention claimed, do those differences constitute steps that would have been obvious to the person skilled in the art?

Any of the above outlined tests may be used to determine whether or not a particular invention has an inventive step properly so-called.

Industrial applicability

The last requirement is industrial applicability. An invention shall be considered industrially applicable if it can be made or used in any kind of industry. It must be noted that for an invention to be patentable, it must have practical usefulness. For an invention to be patentable, it must satisfy the general utility, specific utility and beneficial utility requirements. General utility means that the invention must work. Specific utility means the invention must have some practical applications. Lastly, beneficial utility means the invention must be socially beneficial.

Disclosure and sufficiency

Disclosure

The exclusive right of a patentee to stop others from making or using their invention for a defined period is balanced by the obligation to disclose the invention in detail. This serves two purposes; firstly after the period of exclusivity ends, others can make and use the invention. Secondly, the disclosed invention becomes the basis for further technological advancement and research.

Before patent protection is granted, the invention must be disclosed ostensibly in a codified manner. The disclosure should capture the best mode to carry out the invention for a Person Having Ordinary Skill In The Art (PHOSITA) to carry it out without hindrance.

The US Supreme Court affirmed the decision of the courts below in Amgen Inc v. Sanofi. The courts below correctly concluded that Amgen failed “to enable any person skilled in the art . . . to make and use the [invention]” as defined by the relevant claims. The Supreme Court held that “the patent “bargain” describes the exchange that takes place when an inventor receives a limited term of “protection from competitive exploitation” in exchange for bringing “new designs and technologies into the public domain through disclosure” for the benefit of all”.

The absence in the specification of sufficient information to enable others to learn and practice one of the 6 of the embodiments of the claim was fatal to its validity. The Federal Circuit held that, “[t]o be enabling, the specification… must teach those skilled in the art how to make and use the full scope of the claimed invention without ‘undue experimentation.”

Since the sixth permutation was either impossible or would have required undue experimentation the Federal Circuit held the claim was invalid for lack of enablement because enabling five out of six permutations was not sufficient.

Sufficiency

The United Kingdom Supreme Court held that: “It is a general requirement of patent law both in this country and under the European Patent Convention (“EPC”) that, in order to patent an inventive product, the patentee must be able to demonstrate (if challenged) that a skilled person can make the product by the use of the teaching disclosed in the patent coupled with the common general knowledge which is already available at the time of the priority date, without having to undertake an undue experimental burden or apply any inventiveness of their own. This requirement is labelled sufficiency. It is said that the invention must be enabled by the teaching in the patent.”

The requirement of disclosure is not complete where the disclosure is not sufficient. To be deemed sufficient, a PHOSITA must be able to practice the invention based on the disclosure made by the Patentee.

Instances where the exclusive practice of patented invention can be side-stepped

Trips flexibilities

Trips flexibilities are legal mechanisms that enables member-states to express specific needs in terms of public health, in spite of the patent protection in force. World Trade Organization (WTO) member states may develop their own criteria for patentability requirements. That is novelty, inventive step and industrial application.

General exceptions including Bolar exception for WTO members. Members may provide limited exceptions to the exclusive rights conferred by a patent, provided that such exceptions do not unreasonably conflict with a normal exploitation of the patent and do not unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of the patent owner, taking account of the legitimate interests of third parties.

Member states of WTO are permitted to engage in compulsory licensing. A non-voluntary licence may be granted by a duly authorized administrative, quasi-judicial, or judicial body to a third party to use a patented invention without the consent of the patent holder subject to the payment of adequate remuneration. Compulsory licensing for export purposes is an additional protocol for WTO members who do not have manufacturing capabilities. Parallel importation is one of the avenues countries can use to go round the strict application of patent system. That is goods legitimately placed on another market may be imported without permission of the rights holder. These strategies are used by countries to circumvent the strict application of patents.

Other strategies

In addition to the TRIPS Flexibilities, countries have instituted other strategies such as the use of social responsibility index by the United States. Social Responsibility Index is used as a way to strengthen drug distribution infrastructure, giving discounts to developing countries, and conducting R&D for neglected diseases. To market one’s drug in United States, one must obtain the required social responsibility index each year. Every company must satisfy this requirement.

The total number of Disability Adjusted Life Years saved (DALYs) as a result of the availability of the firm’s product throughout the world divided by the firm’s size which is determined by the firm’s global revenue during the year gives the index. There are several ways by which a company can improve its social responsibility index.

Differential pricing also known as price discrimination or tiered pricing in many instances is where different prices are charged for the same products or services. It can also come about where different consumers are charged different prices for different versions of a product or service. In the context of pharmaceutical and other health products, differential pricing is the adaptation of product prices to the purchasing power of consumers in different geographical or socio-economic segments.

Usually the only difference arises from the prices but when it comes to the benefits the goods or service delivers, it remains intact. Differential pricing can enhance access while preserving incentives for innovation. Thus it would benefit patients in both developing and developed countries in the long run. Differential pricing is a great way to make essential medicines accessible to many people in developing and middle-income countries. It can also lead to incremental sales for the firms involved. Price discrimination therefore presents a win-win situation for the manufacturer and the patient.

One way that is tried and tested to enable expanded access to innovative medicines across Low and Middle-Income Countries is public health-oriented non-exclusive voluntary licensing of Intellectual Property Rights. This approach has been shown to lead to stronger sustainable generic manufacturer competition in more countries faster, driving medicine prices down to lower-than-tiered prices, and creating both economic and health impacts.

With this approach, the patentee permits other manufacturers to make a generic version of the original molecule. This helps to reduce the price to the patient. There are a host of generic manufacturers in India, China and Brazil. There is a technology transfer agreement between the patentee and third parties paving the way for full disclosure to be done leading to enhanced production.

Public-health voluntary licensing of intellectual property rights has been highly effective in supporting the scale-up of World Health Organization (WHO)-recommended Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and Hepatitis C virus treatments in low-income and middle-income countries, saving both money and lives.

Covid-19 vaccine

Countries around the world have suffered the ravages of COVID-19. Many low to middle-income earners have been pushed below the poverty line with a widening inequality gap. People have lost their lives, some have lost their sources of livelihood, others are left with chronic sicknesses that have negatively impacted their quality of life, and in some cases, economies have become moribund with many citizens hardly able to make ends meet. As a result, some countries have made efforts to protect the lives of their citizens. While few have successfully produced vaccines to protect the majority of their citizens many are still struggling to protect half of their populations.

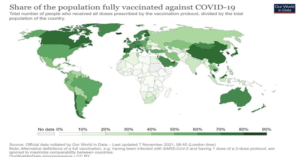

The data above shows percentage of the population of various countries fully vaccinated as of 7th November 2021. The situation as of 7th November 2021 has not significantly improved that much. As shown above, many developed countries had vaccinated the majority of their population while low to middle-income countries are still struggling to get the needed vaccines to protect their citizens. The trend above means that developed countries have what it takes to protect their citizens while third-world countries look helpless in the face of the global challenge.

Challenges current patent regime poses to vaccine manufacture

The current patent system operates on the concept of quid pro quo. In the case of Universal Oil Prods. Co. v. Globe Oil & Refining Co. it was held that “[T]he quid pro quo [for the patent grant] is the disclosure of a process or device in sufficient detail to enable one skilled in the art to practice the invention once the period of the monopoly has expired, and the same precision of disclosure is likewise essential to warn the industry concerned of the precise scope of the monopoly asserted.”

Per this arrangement, the state guarantees the exclusive right to a patentee to benefit from his invention. The patentee has 20 years to practice the invention exclusively, devoid of any competition. In exchange, the patentee ostensibly discloses his invention in a manner that will permit a PHOSITA to practice the invention.

This mutually beneficial relationship between the state and patentees is what sustains and fuels discoveries around the world. It has been the backbone and the anchor upon which the patent system is grounded. There is enough motivation and incentive to entice organizations and individuals to invest in research and development leading to discoveries and inventions that are beneficial to humanity.

A patent must: teach a person of ordinary skill in the art how to make and use an invention, provide an adequate written description of the invention, and (at least technically) disclose any best mode the inventor knows as the most effective way of practicing it.

Robust patent disclosure is a key component of the patent system to ensure that third-party manufacturers can effectively produce their own versions of the invention once the patent expires. The US Supreme Court in the case of United States v. Dubilier Condenser Corp. Upon expiration of [the patent] period, the knowledge of the invention inures to the people, who are thus enabled without restriction to practice it and profit by its use. To this end the law requires such disclosure to be made in the application for patent that others skilled in the art may understand the invention and how to put it to use.

While the public can only practice the invention after the expiration of the patent, the disclosure is done at the time the patent is granted. In practice, public disclosure often occurs even earlier, as most pending U.S. patent applications are published 18 months after filing.

Why can’t third-party manufacturers synthesize covid-19 vaccine?

The key question that COVID-19 has brought to the fore is that if biopharmaceutical patentees have disclosed their inventions as required by law, why are third-party manufacturers unable to manufacture these vaccines leading to uneven distribution of vaccines around the world? As a result of the inequality, some countries like South Africa and India have put forward a suggestion to waive COVID-19 vaccine patents to make the vaccines accessible.

Biopharmaceutical patentees have strongly rebutted this suggestion because weakening COVID-19 vaccine patents will not necessarily increase production by third-party manufacturers especially the latest generation of mRNA vaccines. This inability stems from the lack of proprietary tacit knowledge and trade secrets that third-party manufacturers are not privy to. These are information available only to the biopharmaceutical firms.

Tacit knowledge refers to personal, experiential knowledge that is not amenable to codification. Trade secret on the other hand is uncodified technical knowledge that firms deliberately keep secret. In general, a trade secret encompasses technical or business information that is the subject of reasonable efforts to maintain secrecy and that derives economic value from such secrecy.

For example, a professional tennis player could write instructions on how to serve a tennis ball, but such instructions would necessarily fail to convey tacit knowledge derived from years of training, inherent athletic skill, and even muscle memory. In the technological context, tacit knowledge refers to “non-codified, disembodied know-how” that resides in the mind of an inventor.

It encompasses “intangible knowledge, such as rules of thumb, heuristics, and other ‘tricks of the trade.”. In the context of COVID-19 vaccines, biopharmaceutical patentees have developed tacit knowledge in the course of developing and commercializing their vaccines, and they argue that third parties cannot manufacture these vaccines in industrial quantities without it.

Tacit knowledge ordinarily is not amenable to codification. Moreover, the requirement of disclosure does not require patent applicants to disclose tacit knowledge. Patentees are therefore free to keep tacit knowledge and trade secrets to themselves. Patentees are only required to disclose their invention ostensibly.

Additionally, the patent disclosure requirements focus on enabling a basic version of an invention, which may be a far cry from a fully developed commercial product. This emphasis on enabling a basic version of an invention serves to limit patent disclosure, particularly given that inventors tend to file patent applications as soon as possible on early-stage, embryonic inventions.

Again, priority rules discourage patent applicants from adding “new matter” to their disclosures after filing. “No amendment shall introduce new matter into the disclosure of the invention”. The addition of “new matter” may lead a patent applicant to lose an original priority date and establish a less desirable later one. Although patentees gain valuable insight into their inventions that make them commercially viable, they are not allowed to update the initial disclosure. This is one area that sometimes inhibits a PHOSITA from practicing an invention.

While many inventions can be practiced by a PHOSITA upon disclosure of the invention by the patentee in compliance with the patent system, same cannot be said of COVID-19 Vaccines which require additional tacit knowledge and trade secrets to be disclosed before they can be manufactured by third parties. The law does not require biopharmaceutical patentees to disclose tacit knowledge and trade secrets before their vaccines can be patented. This scenario therefore highlights the cracks in the current patent regime.

This means that even after 20 years of exclusivity enjoyed by the patentee, the public may still be held to ransom by the patentees since third-party manufacturers may still lack the tacit knowledge and trade secrets that will enable them to manufacture the vaccines. Not only does this development stifle access to COVID-19 vaccines but also reveals the deep cracks in the quid pro quo arrangement upon which the patent system is grounded.

The state and by extension, the public are denied what it should get in return for granting 20 years of protection to biopharmaceutical patentees. The benefit the state gets. This defect defeats the whole purpose of patent protection. The weakness leaves so much power in the hands of Biopharmaceutical patentees who may still control the manufacture of COVID-19 vaccines even after the expiry of the 20 years. This defeats the purpose of the quid pro quo arrangement that underlines the Patent system.

The challenges in vaccine manufacture makes it impossible for TRIPS Flexibilities to be applicable. This is because if a country institutes any of the strategies discussed above without the proprietary tacit knowledge and trade secrets, it will still be handicapped in successfully materializing the strategy. So far it. Moderna entered into a ten-year “strategic collaboration agreement” with Swiss chemicals and biotechnology company Lonza to manufacture Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine.

Far from a one-off engagement, this long-term agreement provides for active technology transfer from Moderna to Lonza. With this partnership, Moderna will be able to transfer the needed tacit knowledge and trade secrets to Lonza to pave the way for them to manufacture the COVID-19 vaccine. The difficulty is that so much power is left in the hands of the biopharmaceutical patentees which could lead to exploitation.

There is no guarantee that after the expiry of the 20 years, third-party manufacturers will be equipped enough to manufacture the vaccines without the involvement of the patentees. A suggestion put forward by India and South Africa was shot down by some Western countries.

Their suggestion was for manufacturers in high-income countries to relinquish their intellectual property rights over COVID-19 Vaccines. This according to them would pave the way for third-party manufacturers to produce COVID-19 Vaccines. The suggestion was met with opposition from members of the European Union and the United Kingdom.

Patent holders rarely share their experiential knowledge, which sometimes is key to practicing the invention. Waiver of some legal requirements alone is not enough to address the challenge faced by third-party manufacturers of COVID-19 vaccines. Increased capacity, acquisition of technical knowledge, and regulatory recognition are needed to ensure the successful manufacture of COVID-19 vaccines.

Due to the challenges outlined above, Ghana and other Low-Income Countries have still struggled to bridge the inequality gap in vaccine availability. Therefore making vaccines available requires more collaboration among partners, increasing manufacturing capacity in LMIC and providing new legal mechanisms to share technical production processes.

Way forward

Modification of the current disclosure requirement. Patent law as it exists now needs modification to address the deep cracks in it. The threshold of disclosure must be raised to make patentees disclose their inventions in ways that will make it possible for third parties to manufacture same in commercial quantities without hindrance. The disclosure should be such that a PHOSITA should be able to practice the invention based on the public disclosure made.

Biopharmaceutical manufacturers whose inventions require the transfer of tacit knowledge should not be left off the hook with only ostensible disclosure. The disclosure must include the codification of such critical knowledge that is experiential in nature without which their inventions cannot be practiced. Where there is a need to disclose tacit knowledge, patentees must satisfy that additional requirement to avoid a repeat of what is currently happening with the COVID-19 vaccine.

There should also be an avenue for more information to be added after initial disclosure is done. Once initial disclosure is done patentees are not permitted to update the information provided. Usually, the initial disclosure addresses issues that bother on the incubation period of the invention. It does not touch on key aspects of the invention that permit commercial production of the invention.

There must be a way for patentees to amend their disclosure in ways that will afford third parties the opportunity to manufacture same once the patent expires. While the current regime does not permit amendment to be done, there is a need to remove such barriers to make a way for the disclosed information to be updated once new information becomes available to the patentees.

Government should endeavor to fund research into discoveries. When research is publicly funded, the innovators have no qualms disclosing the invention ostensibly and making available all the tacit knowledge and secrets that are not amenable to codification. A classic example is the Trump Administration’s funding of COVID-19 vaccine production in what was dubbed Operation Warp Speed which led to the discovery of COVID-19 vaccines in record time.

This made it possible for the US Government to have enough doses for its population. In April 2020, the Trump Administration launched Operation Warp Speed, an ambitious initiative aimed at producing 300 million doses of safe and effective COVID-19 vaccine.

This initiative provided about US$18 billion to six vaccine developers, including Moderna, Pfizer, and Johnson & Johnson. Operation Warp Speed provided vaccine developers with several kinds of financial support, including grants to cover vaccine development, advance-purchase commitments for final doses, and, in some cases, both. In addition to financial support, Operation Warp Speed also provided logistical and operational support to expand manufacturing capacity for some grantees.

Federal support helped rapidly accelerate vaccine development. While it ordinarily takes three to nine years to move from sequencing a virus to Phase 1 clinical trials, in the case of COVID-19 vaccines, that time period was significantly condensed to about ten weeks. Public funding of research into discoveries give government agencies the bargaining chip to ask for codification of tacit knowledge and trade secrets.

Government agencies can leverage public innovation funding to essentially bargain for greater codification and disclosure of private technical knowledge. After pumping billions into Operation Warp Speed, the Federal Government should have included clauses in its contract with the vaccine developers to make it mandatory for them to disclose the much-needed tacit knowledge and trade secrets.

Government funded research into new discoveries must be aware of the inherent limitation in the disclosure requirement. Government officials must insist on tacit knowledge disclosure in its contracts with private institutions that undertake research for the government.

High Income Countries can institute Social Responsibility Index as instituted in the United States to compel biopharmaceutical companies to make their medications that are protected by patent become assessable to the people living in low-income countries.

For a pharmaceutical company to operate in United States, it must have the social responsibility index that shows that it has made it innovative medicines protected by patents available to people in third-world countries. Other developed countries may adopt this approach to increase access to innovative medicines in developing countries.

Conclusion

This paper discussed patent law in its entirety. The very foundations upon which patent law is grounded was analyzed. The discussion also centered on the various eligibility requirements for the grant of patent.

Not only these but also the challenges that have saddled the current patent system were highlighted. Strategies to surmount these challenges to usher in a more effective way of utilizing the quid pro quo arrangement that underpins the patent system were proffered. Public disclosure in its current form leaves much to be desired because of its inherent limitations as outlined clearly in this paper. Reforms must be put in place to make sure countries are not held to ransom by biopharmaceutical patentees should a pandemic strike again.

Also, as new inventions are churned out day in day out, some inventions may require tacit knowledge disclosure before they can be practiced. Failure to address the cracks identified leave so much power in the hands of patentees which may be subjected to abuse and exploitation.

It can be used as a bargaining chip to hold countries to ransom. Hence, the time has come for the necessary amendments to be made to the disclosure requirement of patent to forestall any future difficulties that may arise.

>>>the writer is a Lawyer/Pharmacist, currently with the IP/Commercial Team of Minkah-Premo, Osei-Bonsu, Bruce-Cathline & Partners. He can be reached via [email protected] and or +233501412922