By Makafui AIKINS

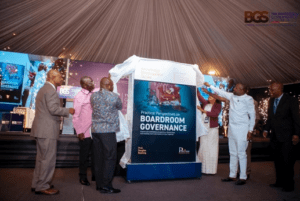

Let me start by saying that not only is the book, ‘Practical Perspectives on Boardroom Governance’ by Prof. Douglas Boateng an insightful, enjoyable, and easy read, but it is also a very luxurious one.

Holding this portable hardcover, debossed cover-text, rich and glossy-paged, and well-bound book in hand, and knowing full well that it was written, designed, and printed in Ghana by Ghanaians, I tell you, I felt very patriotic and proud—as though I had a hand in it myself. I didn’t.

Don’t judge a book by its cover, they say. But in this particular case, you would be right to favourably judge this book by its look—even before diving into it.

You would be right to do so because I spent the weekend reading it, and I must say, my excitement over its exterior was topped by that which I felt from its interior—the rich lessons on corporate governance driven by effective boardrooms, as contained therein.

One particular speaker, during the book launch held on Tuesday, 8th October, commented that he just could not put down the book once he started it. My experience was no different. This 175-paged hardcover book is indeed a hard book to put down once one begins it. You and many others who finally get to read the book will find this to be the case with you too.

The lessons

Who are directors? As a business owner, as an employee of someone else’s business, and as a tax-paying citizen in a nation awash with various state entities, what do board of directors mean to you?

What is the scope of their responsibilities? What are their limitations? Who can become a director? What is the right composition of boards (for both public and private sector entities alike)—not only in terms of what is legal, but also, what is expedient? What are the implications of boards? What powers do they wield? Why do they matter?

What is effective corporate governance—and how does an organisation reach this feat? What are the roles of directors in helping achieve this feat? What are the regulatory stipulations on corporate governance—what is legal and what is not? What are the implications for acting illegally—what is the scope of liabilities of directors as per the law? Could a person ever end up in jail in this position of director? (The answer is yes, by the way).

What sets directors apart from managers? How do companies manage the nuances existing between these two different roles—these two different groups who ultimately have the duty of working towards a singular corporate goal? How are directors to act so as to not overstep—and not descend into micromanagement, unethical, and outright illegal behaviours within the organisation?

You have heard these two terms a lot: executive and non-executive director… What is the difference between these two roles? Are their duties under the law any different? Can an executive director, particularly a chief executive officer (CEO) or a managing director (MD) serve as board chair? First of all, is that legal; and secondly, is it expedient? And, by the way, you have heard these two terms used interchangeably a lot: CEO and MD. Are there, by any chance, any difference between them?

Who is a board chair and what are their responsibilities? What sets a successful board chair apart from a failed one? Who can (by law) and must (by common sense), be appointed to the position of chairperson? And when so appointed, how should a board chair act?

The tendency to think that chairpersons are supposed to be faceless individuals reserved to be at the back of the corporate machinery unseeingly stirring the overall affairs of organisations is high. Yet, we find in the law, as pointed out by Prof. Boateng in this book, a reality that is completely different.

The matter of the role of the board chair, brings to mind that of the CEO (and their public sector equivalents like director generals, chief directors, etc.,), the company secretary (and their public sector equivalent: board secretary), and other members of executive management such as the chief operating officer (COO) or Chief Supply Chain Officer (CSCO), the chief finance officer (CFO), etc.

What are the roles, responsibilities, and qualities required of these persons within the organisation? In the case of company secretaries for instance, who can hold such positions? Can an artificial person (a body corporate), just like a natural person, serve as a company secretary? And is the role restricted to lawyers only?

What different types of boards are there to explore? What is a unitary (single-tiered) board and a two-tiered one? Which is more prevalent in Ghana and which is more advisable depending on your particular type of organisation? What are the emerging trends or changes on this front?

Under what circumstances can boards be said to have acted ultra vires—in what circumstances must they refer to shareholders for prior approval before they can act? What are the differences between shareholders and board of directors? What factors must a person consider before accepting the role of director?

These and many more are the issues thoroughly tackled in this book. And in so tackling, Prof. Boateng adopts an ingenious approach; one which I would like to term as a ‘tentacled perspective’.

The tentacle perspectives

Indeed, in addressing all these issues, one thing that stands out in Prof. Boateng’s work is the tentacled—broad—perspective he adopts. Never in the book are perspectives one-dimensional.

Things are, at all points, looked at, among others, from a cross-national and cross-jurisdictional point of view, from both a legal and ‘common-sensical’ perspective, from a public sector and private sector organisation perspective, from a small to large organisational point of view, from a multi-sectoral perspective, etc.

And you get this sense right from the opening paragraph of the book. When defining the term: board of directors, he, of course, reaches for the Ghanaian definition as set out in the Companies Act, 2019 (Act 992): “those persons, by whatever name called, who are appointed to direct and administer the business of the company.”

But tellingly, he first makes reference to the South African and UK definitions: “A person who, by any title, undertakes that role by offering relevant directional input and guidance.”

Of course, ultimately, these two different definitions convey the same meaning. But it is telling that right from the get-go, the Ghanaian, the African, the European, etc., holding this book, will find themselves, all throughout the text, not cut out from the conversation.

They will find in this book, a brilliant attempt at unifying the concepts and rules behind corporate governance. As a staunch proponent of the conscious upliftment of the Ghanaian and African to the position of globally recognised thought leaders across all fields, this approach adopted by Prof. Boateng excited me endlessly.

The skill of balance

In this book, you will find Prof. Boateng skilfully navigating, and taking you through the often-nuanced terrain that is corporate governance. Like every aspect of our national lives and economy, the concept of corporate governance has within it, certain subtle yet highly consequential nuances—ones requiring the employment of expert skill.

For instance, regarding the role of executive directors (such as CEOs and MDs), he notes, “The executive directors strike a balance between their management of the company, and their fiduciary duties and concomitant independent state of mind required to serve on the board.” He then goes on to prescribe the ‘how’.

For indeed, one of the most daunting challenges faced by CEOs and MDs tend to be the challenge of balancing the responsibilities they have towards the board and that which they have towards the actual management of the organisation and its stakeholders (such as employees, clients, etc). It takes skill to be able to strike this balance so well that there never is the accusation of the CEO/MD being partial to one group to the disadvantage of the other.

We see yet another nuance at play when it comes to the duty on boards to be independent thinkers, yet have great chemistry and a flourishing team spirit. Prof. Boateng shows how these two virtues can co-exist—i.e., how the call for teamwork and consensus is not a call for group-think and the removal of the independent powers of thought granted each board member.

Perfecting the system

Yet another theme that runs through in this book is that of efforts constantly being made by stakeholders—government / private entities and individuals alike—to help shape the corporate governance system within the country… To keep it at par with global standards—an effort that will ultimately result in the boosting of the nation’s business environment, and consequently cause sustained economic growth.

He shows how case laws (by the judicial system), self-regulation strides made by entities like the Institute of Directors (IoD), legislations (such as the Companies Act, 2019 (Act 992)), etc., have caused certain needed changes to the corporate governance systems in the country.

Notably, he points to the enactment and streamlining of the responsibilities, qualifications, consequences (punitive measures for non-compliance), etc., of board directors, board chairs, and company secretaries as one of the crucial ways that the law and the regulatory climate has drastically caused an improvement in the corporate governance systems within the country.

“Being a director today comes with consequences for the person involved. They include the potential jail sentence, or a heavy fine for negligence, and for destroying shareholder value,” he notes.

And it is the same for CEOs/MDs especially of public sector organisations, he points out. It is a common problem in African countries where CEOs and MDs are ‘handpicked executives’ and ‘specially selected’ individuals who have “no detailed job description and performance contracts”, hence making measurement of their job performance and value addition difficult.

These persons often have no qualities to occupy these positions…They “are politically chosen and do little more than nod to requests from external influencers with own vested interests and not necessarily shareholder, organisation, sector, and nation building interests.” “In line with the Companies Act, it is essential that CEOs/ MDs only account to the board and not to any external individuals and special interest groups who in most cases are not shareholders,” he writes.

One other exciting perspective categorically captured throughout the book is that of the evolved responsibilities incumbent on organisations—cutting across all forms, sectors, sizes. And it is the responsibility of sustainability.

The duty on organisations to have as their ultimate end, not only the protection and increasing of shareholder value, but also, the interests of the societies within which they operate and the nation at large. This presents with it some form of nuance and the alteration of certain corporate dynamics, which Prof. Boateng expertly covers in the book.

Touching on flaws

The book doesn’t end without him, as expected, pointing out certain flaws that still remain in the Ghanaian corporate governance ecosystem. The issue of what he calls ‘handpicked executives’ or ‘specially selected’ individuals—persons, who, as already mentioned, have no real qualifications or skills for the jobs/positions they are appointed to. This issue still remains a huge impediment to corporate governance in the country—especially when it comes to the public sector.

In some organisations—especially small companies and even large privately-held companies—within developing countries such as ours (and large economies such as the US, in fact) you sometimes find the roles of CEO and chairperson combined. This combination, he notes, can “often lead to transparency and accountability issues.”

The demographic

I have already touched on the wide expanse of this book’s themes. What this broad-theme format has done is to create for the book, a very wide and varied expanse of target readers.

From the expert to the organisational novice (the new business owner and the person contemplating starting a business who wants to adopt a much more robust, world-class business approach), to the management of established organisations; to the individual who is currently serving on board(s), or that person presently receiving offers to serve on boards; to the employee who wants to better understand what good corporate governance comprises so as to better appreciate or critique their organisational leaderships, to the citizen hoping to get a better understanding of how systems ought to work so as to better undertake their rights/duties of keeping governments on their toes, especially regarding the management of public entities; to the Ghanaian, African, and the world at large; to students cutting across all levels and fields of study.

I, for one, know that having access to such a book during my time in law school—or even in business class in SHS for that matter—would have made Company Law a much easier course, for the book does a great job of putting things in real-life context.

Conclusion

Calling this an insightful book is almost an understatement. All throughout the book, you are educated on not only what is legally acceptable, but also what is advisable. On the back of his almost-three-decade’s experience serving on diverse boards across multiple countries, Prof. Boateng indeed does not only offer you insights as to what is right (by law), but also, what is expedient (by experience).

Directorship is no ceremonial position—at least, this is no longer the case. One cannot expect to carry out this task half-heartedly. Directorship is serious business—as it ought to be. “Contrary to popular belief, a directorship is a profession requiring the highest level of professional competence.”

Especially in this sustainability-driven world of ours. Prof. Boateng notes. And, as mentioned, with our revised Companies Act, the stakes are very high for such persons who perform this role. Essentially, board of directors can make or break organisations; in turn, organisations can make or break their board of directors.

And the position of board chair, it is more hands-on than many are expected to believe. Some experts even recommend that the position should be reserved for independent non-executive directors, and definitely not be given to the CEO/MD of the organisation. Prof. Boateng seems to agree with this sentiment. I could go on and on with the lessons contained in this book. But it is best I end it here, and leave the rest for you to uncover for yourself.

Indeed, this 175-paged hardcover luxurious-looking book is a hard one to put down once one begins it. I could, at no point, give it a cursory read, for each item contained in it is very crucial. I took meticulous notes throughout the entire two days I spent on it. It is great both as a quick read and as a reference work.

In this highly-globalised world, and in our case, in this AfCFTA-era where intra-continental trade and dealings are to become more common-place, it is important that every organisation—big or small—begins to adopt the highest standards when it comes to corporate governance. And boardrooms, they are where the magic begins. ‘Practical Perspectives on Boardroom Governance’ by Prof. Douglas Boateng shows you how.

>>>the writer is CEO & Co-founder of Nvame, a premier business development consultancy and publication firm. She can be reached via [email protected], www.nvame.com