… Key to economic prosperity?

By Solberg Horve MISHIWO

Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs) are major economic growth drivers in developed and developing nations (The Business and Financial Times, 2024). These enterprises are vital to Ghana’s rising economy, contributing to employment and Gross domestic product (GDP).

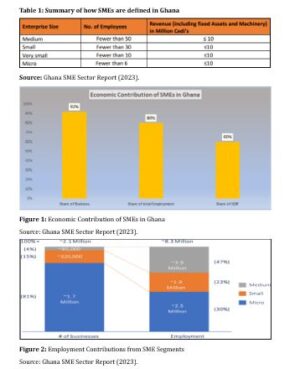

Despite limited statistics on their growth and development, 92% of registered companies in Ghana are SMEs. Furthermore, Small and Medium Enterprises create 85 per cent of manufacturing jobs and contribute 70 per cent to the national GDP (Ghana SME Sector Report 2023).

On the other hand, Ghana’s Micro, Small & Medium Enterprises (MSME) sector has an estimated 2.1 million businesses, with approximately 1.7 million classed as micro-enterprises. These enterprises employ around 2.5 million people (30% of total MSME employees), meaning that each micro-enterprise creates 1-2 jobs.

See Figure 1 and 2.

This evidence confirms that SMEs have a substantial influence on economic growth and development, as well as on employment and income. Despite their important role, however, many SMEs in the country still struggle with the rising cost of taxes (Peprah, Abdulai & Agyemang-Duah, 2023).

Table 1 presents what SMEs represent in Ghana.

This article examines whether the Ghana Revenue Authority’s (GRA) tax enforcement strategies with SMEs align with the government’s economic goal of shifting the economy from one focused on taxes to one focused on production. Therefore, this article will begin by exploring government’s economic plan and what SMEs represent in the Economy of Ghana. Second, the paper will look into data on how aggressive taxes affect SMEs. Third, we will look at the theory and real-world connection between taxes and production, comparing Ghana’s methods to those used by other nations. Lastly, policy suggestions will be made to find a balance between taxation and helping the growth of small businesses.

Economic Vision of Ghana

As this article progresses, it is crucial to look into the Government of Ghana’s economic vision, which aims to transition from a taxation-heavy economy to a production-oriented one. This shift is part of a broader strategy to foster sustainable economic growth, reduce unemployment, and enhance the country’s industrial base. In line with this vision, the Government has articulated plans to increase investments in manufacturing, agriculture, and technology sectors. The Ministry of Finance’s 2021 budget statement emphasized the need to build a resilient economy by supporting local industries and reducing the reliance on imports (Ministry of Finance, 2021). This approach aligns with “Ghana Beyond Aid” agenda, which seeks to leverage the country’s resources and human capital to create a self-sustaining economy.

In the background of this article, SMEs’ formidable role in Ghana’s economic landscape has been established, significantly contributing to GDP, employment, and innovation. See Figure 1 and 2 in the previous above. Moreover, the Ghana Revenue Authority (GRA) has implemented several tax policies to generate more revenue for the nation. However, evidence revealed that these taxes have imposed significant financial burdens on SMEs (Koranteng et al., 2017; AGI, 2022). Tax rates have increased in the past few years, and new taxes have been implemented. For instance, between 2019 to 2022, Government of Ghana introduced Electronic Transfer Levy (E-levy), COVID-19 Health Recovery Levy, Sanitation and Pollution Levy, Financial Sector Clean-up levy. Again, on 29 December 2022, the President of Ghana assented to the bill passed by Parliament, thereby formalising the increase in the standard Value-Added Tax (VAT) rate from 12.5% to 15%, which took effect 1 January 2023. SMEs have difficulty with their finances because of these extra taxes and levies. Many of them are still recovering from the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the economy. The Association of Ghana Industries (AGI) in a survey found that 75% of SMEs identified high taxes as one key factor impacting their growth and business sustainability, while recommending that the Government should focus on agriculture to help the economy grow (AGI, 2022). According to the report, agriculture has been the primary driver of Ghana’s economic growth. Agriculture’s GDP contribution declined from 29.8% to 20.3% between 2010 and 2015. With 44.7% of the workforce employed, it continues to make a significant economic contribution (GLSS6, 2014). Agriculture got 1.3 billion dollars in Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) between 2008 and 2016 (GIPC, 2016).

Impact of Aggressive Taxation on SMEs

SMEs in Ghana have difficulty with financial resources because of higher taxes imposed on them. This, however, reduces their disposable income, limiting their ability to reinvest in their businesses, hire new employees, or expand their operations.

The International Finance Corporation (IFC) (2020) found that high taxes are the major factor that stops small businesses in emerging countries like Ghana from growing. Adding more taxes, like the COVID-19 Health Recovery Levy, has made it difficult for these businesses to recover from the economic effects of the pandemic thereby putting more pressure on their finances.

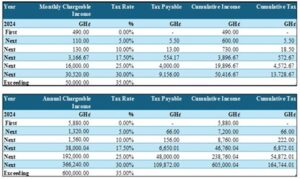

When these taxes add up, they can cut into small businesses’ profit margins, causing some to shrink or close down completely. According to Ayiku (2023), the Ghana Revenue Authority imposes a 25% tax on SMEs. PAYE, Corporate, and Personal Income taxes all apply to SMEs.

See Figure 3. Again, when taxes are high, it discourages people from working hard, save funds or even invest in new enterprises. However, perceptions of fair taxation vary among individuals, resulting to differing views on optimal tax rates, which can influence resource allocation and economic output.

Ghana’s severe tax rules have adversely affected small enterprises. Tee et al. (2016) surveyed 102 managers and executive officers from SMEs in the Ga West Municipality of the Greater Accra Region to determine how tax policies affect SMEs’ growth. The study indicated that most respondents thought tax policies hurt SMEs and called for tax reform. Ghanaian business owners also say the 25% one-size-fits-all income tax unjustly stifles growth and sustainability (GhanaWeb, 2022).

These examples demonstrate how high taxes hurt small enterprises, which create jobs and diversify the economy. Emmanuel (2024) reported in Pulse Ghana Newspaper that Ghana has a 25% corporate income tax, which is higher than that of nearby countries. Business and consumer burdens are increased by the 15% VAT rate, compared to 7.5% in Nigeria, their West African counterpart. High tax rates limit profit margins, making it hard for businesses to innovate, grow, and reinvest (Emmanuel, 2024).

Taxation Vs. Production: Economic Theory and Evidence

Economics’ taxation-production relationship is difficult and contested. Traditional economic theory indicates high taxes reduce investment and entrepreneurship, discouraging production. According to the Laffer Curve hypothesis, the best tax rate maximises income without inhibiting economic activity (Laffer, 1974).

Tax increases over this optimal point can diminish economic output and production. However, public finance theory holds that well-structured taxation can boost economic growth by supporting infrastructure and public goods that increase productivity (Musgrave & Musgrave, 1989).

Strategically, taxing relevant sectors of the economy can enhance productivity and drive long-term economic growth. However, taxation and production incentives must be balanced. Moderate and well-targeted taxation can increase production by encouraging corporate expansion, while excessive taxation can restrict investment and delay economic growth (Feld & Kirchgässner, 2001).

Other nations that have successfully moved to production-focused economies tax differently than Ghana. Singapore balances taxation with economic growth by investing in infrastructure and research and having a low corporation tax rate (World Bank, 2020).

Singapore’s tax policies encourage international investment and local business, creating a production-oriented economy. In the country, for up to 15 years, qualified manufacturers’ export profits were taxed at 4% instead of 40%.

More generally, the incentives seemed to stimulate investment and employment in export-intensive sectors and, later, in sectors that introduced new manufacturing technology to Singapore (International Monetary Fund, 2021). Estonia, on the other hand, has a progressive tax structure that exempts reinvested gains, supporting corporate growth (OECD, 2021).

This strategy has helped Estonia become a knowledge-based economy by improving output and innovation. A smart balance between taxation and production incentives can lead to successful economic transformations.

Empirical evidence shows a nuanced relationship between taxation and production growth. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF, 2018), countries with high corporation tax rates have slower economic growth than those with moderate tax rates. Most OECD nations’ 2018 tax reforms reduced business and individual tax rates to boost investment, consumption, and labour market participation.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act lowered the US corporate tax rate from 35% to 21% in December 2017. The US rate dropped below the majority of OECD countries after this move. Belgium then enacted a tax reform plan that will gradually reduce the Corporate Income Tax (CIT) rate from 33.99% to 25% in 2020 While the UK and Greece have announced plans to drop their CIT rates by 2020, Luxembourg, Japan, and Norway, all reduced their statutory CIT rates in 2018 With the exception of Chile, the OECD reports that CIT rates have decreased in almost all member and partner countries. In additions, CIT rates of 25% or less were observed in six of the OECD’s 2000 survey countries; this year, the number has increased to 38.

In Ghana, recent data indicates that while aggressive taxation has led to short-term revenue gains, it has also coincided with slower production growth. The Ghana Statistical Service (2024) reported a 3% decline in industrial production in 2021, which aligns with increased tax burdens on SMEs. The World Bank (2021) and OECD, ATAF, & AUC (2023) also noted that Ghana’s high taxation has contributed to a larger informal sector, where businesses operate outside the formal economy to evade taxes, thus hindering overall production growth.

However, the report also shows that one of the main sources of fiscal stress is low domestic resource mobilisation, especially due to extensive tax exemptions. Ghana has a low tax-to-GDP ratio. Recent data paints a sobering picture of Ghana’s position in the African tax landscape. In 2021, Ghana’s tax-to-GDP ratio stood at 14.1%, lagging behind the average of 33 African countries, which reached 15.6% in 2023. The country needs to rationalise its tax expenditures, which were estimated at 5% of GDP in 2014.

See Figure 4,5,6,7. Corporate Income Tax (CIT), one of the least efficient taxes, drove recent revenue increases and did little to address equity (World Bank, 2021). Low Personal Income Tax (PIT) receipts indicate the informal economy’s size, which could help social policy goals. Ghana should use VAT and property tax to fund its social policy goals (World Bank, 2021; OECD, ATAF, & AUC, 2023).

From the preceding, Ghana’s economic objective of shifting from a taxation-heavy model to a production-oriented economy appears to conflict with the GRA’s tax enforcement strategies on SMEs. This is because the GRA’s enforcement strategies is hindering the government’s goal of sustainable economic growth and unemployment reduction through increasing investments in industry and agriculture (Ministry of Finance, 2021; Ayiku, 2023). For instance, the COVID-19 Health Recovery Levy and 15% VAT increase create a huge financial burden on SMEs in Ghana (Ayiku, 2023; Emmanuel, 2024). Other evidence showed that with rising taxes, industrial production fell by 3% in 2021 (Ghana Statistical Service, 2024). However, the world bank’s recent report evidenced that high tax rates have also increased the informal sector, as enterprises avoid taxes, impeding formal sector growth and innovation (World Bank, 2021).

Taking a look at the lesson from Singapore and Estonia which showed that taxation and supportive policies have boosted productivity and growth in these countries. For example, Singapore’s production-oriented economy is boosted by low corporate tax rates and infrastructure investment (World Bank, 2020). Ghana differs from these models, which combine high taxes with low company development and investment support.

Therefore, Ghana must consider a more balanced taxation strategy. This can be achieved by lowering tax rates to encourage investment and growth, while rationalising tax expenditures for efficiency and equity. The tax enforcement strategies of GRA must align with the government’s economic policies in order to create a conducive ecosystem that fosters growth and development of SMEs, which in turn will drive economic growth, job creation, and overall prosperity in Ghana.

References

- Association of Ghana Industries (AGI). (2022). SME Growth and Sustainability Report. Retrieved from https://www.agighana.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Industry-Perspectives-Magazine-Vol.5-Qrt-2-2022.pdf

- Association of Ghana Industries. (2021). SME Growth and Sustainability Report. Retrieved from https://www.agighana.org/

- Ayiku, A. (2023, May 9). Impact of high taxes on SMEs. Graphic Business. Retrieved from https://www.graphic.com.gh/business/impact-of-high-taxes-on-smes.html

- Emmanuel, K. (2024, June 27). Burden of taxes in Ghana: Why many businesses are shutting down. Pulse Ghana. https://www.pulse.com.gh/business/burden-of-taxes-in-ghana-why-many-businesses-are-shutting-down/eyewitness

- Feld, L. P., & Kirchgässner, G. (2001). The Impact of Taxation on the Economy: Empirical Evidence and Economic Theory. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 15(3), 23-36. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.15.3.23

- Ghana Investment Promotion Centre. (2016). Foreign Direct Investment Report. Accra: Ghana Investment Promotion Centre. https://www.gipc.gov.gh/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Q4-2016-GIPC-Quarterly-Investment-Report.pdf

- Ghana Revenue Authority. (2021). Taxation Report. Retrieved from https://gra.gov.gh/

- Ghana SME Sector Report (2023). Strategy and Research Department. https://www.gcbbank.com.gh/research-reports/sector-industry-reports/361-sme-sector-in-ghana-2023-v1/file

- Ghana Statistical Service. (2024). Ghana Living Standards Survey Round 6 (GLSS6) Main Report. Accra: Ghana Statistical Service.

- (2022). Small Retail Business Faces Closure Due to Tax Burden. Retrieved from https://www.ghanaweb.com/

- International Finance Corporation. (2020). SME Tax Burden Study. Retrieved from https://www.ifc.org/

- International Monetary Fund (IMF) (2021). Singapore’s Development Strategy. https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/book/9781557754639/ch003.xml

- International Monetary Fund. (2018). Fiscal Monitor: Capitalizing on Good Times. Retrieved from https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/FM

- Koranteng, E. O., Osei-Bonsu, E., Ameyaw, F., Ameyaw, B., Agyeman, J. K., & Dankwa, R. A. (2017). The effects of compliance and growth opinions on SMEs compliance decisions: An empirical evidence from Ghana. Open Journal of Business and Management, 5(02), 230.

- Laffer, A. B. (1974). The Economics of the Tax Revolt. Policy Review, 1(1), 6-13.

- Ministry of Finance. (2021). Budget Statement and Economic Policy of the Government of Ghana for the 2021 Financial Year. Retrieved from https://www.mofep.gov.gh/

- Musgrave, R. A., & Musgrave, P. B. (1989). Public Finance in Theory and Practice (5th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.

- (2021). Estonia Economic Snapshot. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/estonia/

- Peprah, C., Abdulai, I., & Agyemang-Duah, W. (2020). Compliance with income tax administration among micro, small and medium enterprises in Ghana. Cogent Economics & Finance, 8(1), 1782074.

- The Business and Financial Times (2024). Taxation Systems and Policies: A killer of SMEs?. https://thebftonline.com/

- World Bank. (2020). Doing Business 2020: Comparing Business Regulation in 190 Economies. Retrieved from https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/doing-business

- World Bank. (2021). Ghana Economic Update. Retrieved from https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/61714f214ed04bcd6e9623ad0e215897-0400012021/related/Ghana-Rising-Accelerating-Economic-Transformation-and-Creating-Jobs.pdf

Web Link

- The Political Economy of ‘Tax Spillover’: A New Multilateral Framework” by Andrew Baker and Richard Murphy (forthcoming in Global Policy).

- https://unctad.org/en/PublicationChapters/diae2018d4a5.pdf 4.

- 4https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5a0c602bf43b5594845abb81/t/5a78e6909140b73efc08eab6/1517872798080/ICRICT+Unitary+Taxation+Eng+Feb2018.pdf

- https://www.oxfam.org/en/research/tax-battles-dangerous-global-race-bottom-corporate-tax

- https://gabriel-zucman.eu/files/TWZ2018.pdf

Profile summary:

The writer is a Chartered Accountant and Chartered Tax Practitioner with extensive experience in tax consulting, management consulting, and auditing. He has provided strategic guidance to numerous local and multinational businesses by offering valuables insights and expert opinion on financial and tax matters. He is a member in good standing of both Chartered Institute of Taxation, Ghana and Institute of Chartered Accountants, Ghana.

He can be reached via:

M: 0248 887 053

E: [email protected]

LinkedIn: Solberg Horve Mishiwo

X: @Solberg_Horve

Instagram: iam_solberg