By Ebenezer M. Ashley (PhD.)

Generally, prolonged civil conflicts in certain parts of Africa have the tendency to stall economic development and growth by starving foreign direct investments, which feed essentially on stable political atmosphere and friendly business environments. The imminent question is: if African and other regional economies are struggling to create congenial environments for businesses to thrive, how prepared are they to implement youth-centred programmes that would assure effective development and contribution of young people to national growth?

Juneja (n.d.b) opined, the regulatory environment in most economies is characterised by many and complex compliance requirements. To be abreast of and compliant to the regulatory requirements, the young entrepreneur would have to invest time and effort, continually, in the study of the regulatory requirements. The author noted however, variations in business registration requirements from one country to the other. This notwithstanding, the number of government departments, agencies and compliance requirements could prove handful to the young and inexperienced entrepreneur in a given country.

Brief comparative analysis by Juneja (n.d.b) revealed while one registration is required in some economies, between two and twenty registrations are required in other economies such as Paraguay and Uganda. Administrative cost of registering a business in countries such as Syria and Yemen is high. However, no administrative cost is incurred in registering businesses in Denmark and other related economies. UNESCO (2016) found, due to the absence of more sophisticated skills required to establish complex business entities, many young entrepreneurs in developing economies settle for businesses with low-skills requirements; and sectors that are easy to penetrate and transact businesses.

The World Economic Forum’s report for 2017 suggested, given the youthfulness of their respective populations, countries in Sub-Saharan Africa stand the chance of adding about $500 billion annually to their economies for the next thirty years. The estimated increase in annual economic earnings, that is, $500 billion, represents about a third (1/3) of the continent’s (Africa’s) gross domestic product (GDP). Similarly, the World Bank believed Africa’s young population is a perfect opportunity for economies in the region to increase their gross domestic product between 11% and 15% from 2011 through 2030.

However, the foregoing economic success story is predicated on massive investment in education; and creation of jobs in the various economies in Sub-Saharan Africa. In the absence of sound education and job opportunities, African economies risk of experiencing social and economic unrests, especially from the youthful population.

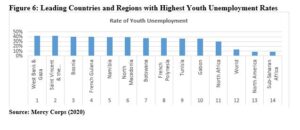

It is worth-emphasising, increase in social vices such as pilfering, theft, armed robbery, cyber fraud, early school drop-out, teenage pregnancy, and drug abuse, among others, cannot be ruled out in the absence of structured education and employment programmes in economies dominated by youthful populations. Table 7 and Figure 6 depict data on selected economies and regions with significant youth unemployment rates in recent periods.

Available data in the table and figure suggest the West Bank and Gaza has the highest youth unemployment rate (42%); and Mercy Corps (2021) estimated unemployment rate among young people in Gaza at 70%. This alarming unemployment rate among the youth is indicative of the economy sitting on a time bomb. Efforts by Mercy Corps to train over 2,500 youth in the West Bank and Gaza through the Gaza Sky Geeks programme, so they become computer literates, technologically-savvy; develop apps, learn how to code; and start their own businesses deserve commendation.

Table 7: Leading Countries and Regions with Highest Youth Unemployment Rates

| Rank | Country / Region | Rate of Youth Unemployment |

| 1 | West Bank & Gaza | 42% |

| 2 | Saint Vincent & the Grenadines | 41.70% |

| 3 | Bosnia | 39.70% |

| 4 | French Guiana | 39.60% |

| 5 | Namibia | 39.50% |

| 6 | North Macedonia | 39.10% |

| 7 | Botswana | 37.30% |

| 8 | French Polynesia | 36.90% |

| 9 | Tunisia | 36.30% |

| 10 | Gabon | 36% |

| 11 | North Africa | 30% |

| 12 | World | 13.60% |

| 13 | North America | 9% |

| 14 | Sub-Saharan Africa | 9% |

Source: Mercy Corps (2020)

Mercy Corps (2021) recalled about 100 young people in the West Bank and Gaza have been able to nurse their technology projects for markets in the Arab world. The initiative is crucial at a time when COVID-19 had eroded gains made by many economies in prior and recent years; and the affected countries need external financial and technical supports to revive their respective economies.

Figure 6: Leading Countries and Regions with Highest Youth Unemployment Rates

Source: Mercy Corps (2020)

Nonetheless, in the domain of youth unemployment, performance of Sub-Saharan Africa deserves a thumbs-up; her performance (as shown in Table 7 and Figure 6) is at par with North America (9% apiece). Sub-Saharan Africa’s average (9%) is about 3.3 times better than the rate recorded by North Africa (30%); about 4.7 times superior to the rate recorded by the West Bank and Gaza (42%); and 4.60% (9% – 13.60% = -4.60%) better than the world’s average rate (13.60%). In spite of the good average youth unemployment rate recorded by Sub-Saharan Africa, respective rates recorded by African countries such as Namibia (39.50%), Botswana (37.30%), Tunisia (36.30%) and Gabon (36%) were quite alarming; and about 3 times higher than the world’s average (13.60%) during the period.

Hoetu (2015) observed, the issue of youth unemployment in most economies transcends socio-economic challenge to include threat to national security. For instance, in 2004, the United Nations (as cited in Hoetu, 2015) wondered how the youth, who should be adorned as the world’s greatest assets have been allowed to become a threat to security; a phenomenon which could extend beyond national, sub-regional and regional borders to the global level.

In 2005, youth unemployment rate in West Africa (18.10%) was among the highest in the world. The global youth development index report for 2016 identified Sub-Saharan Africa as one of two regions with overall least development in youth policy implementation. The other identified “culprit” was the South Asian region.

Although unemployment rates among young people in developed economies may be high, structural and institutional arrangements providing financial support tend to minimise the overall adverse effect on the youth. Conversely, there is no gain-saying immediate and recurring practical intervention programmes are required at the national level to nib the growing challenges of high unemployment rates among young people in developing and emerging countries in the bud.

In 1995, Uganda established the Youth Entrepreneurship Scheme (YES) as a publicly-funded programme to provide support for brilliant, but needy young people endowed with creativity, innovation and critical thinking skills in the country. As at 2015, about 1,812 Ugandan youth had received financial support in the form of credit facilities while over 4,000 young people had undergone training and acquired skills in business management (Hoetu, 2015).

Mercy Corps is complementing efforts of the Ugandan government by empowering over 8,600 Ugandan females located near the country’s border with Kenya, so they become self-sustaining and bread-winners for their families. To this end, the mobilised females are trained to acquire financial literacy skills, education in life skills; and resources needed to raise livestock to earn personal incomes, manage their finances; and to support their families (Mercy Corps, 2021).

As revealed by Sambo (2016), Kenya is one of the few countries in Africa to have officially introduced entrepreneurship education to her national academic and training systems; and one of the economies promoting aggressive youth entrepreneurial development through the national Youth Enterprise Development Fund (YEDF).

Hoetu (2015) recounted, YEDF had already assisted in the creation of more than 300,000 employment opportunities within five years. As of 2013, more than 200,000 young entrepreneurs had been trained while financial assistance had been extended to over 157,000 young Kenyan entrepreneurs through the youth enterprise development fund. Through the Youth Employment Scheme Abroad (YESA), the youth enterprise development fund supported some young Kenyans to secure employment opportunities outside the country.

A reality television show developed by Mercy Corps entitled Don’t lose the Plot and aired in 2017 in Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda sought to encourage many young people to perceive farming as lucrative venture. The reality television show attracted over 3.4 million viewers across the three countries. Over 60% of the viewers were believed to be between the ages of 18 and 34; and were predominantly females. Alongside the reality television show, Mercy Corps developed web-based interactive budgeting tool known as Budget Mkononi; and over 5,000 users were enlisted in the first two months (Mercy Corps, 2021).

In addition to state-led intervention programmes in Nigeria and Tunisia, Mercy Corps has initiated programmes to accelerate support for young people in these countries. Since 2011, over 71,780 Tunisian youth between ages 15 and 35 years have been assisted to develop the requisite skills to be more efficient in their respective workplaces and in their lives. The presence of Mercy Corps in Nigeria has already facilitated training of nearly 253,700 females in 536 Junior and Senior Secondary schools in Kano State.

Young people in Guatemala and Iraq were also benefitting from the employment programmes organised by Mercy Corps during the research period. As part of its strategy to complement national efforts at reducing youth violence in urban communities, Mercy Corps organised educational, job-related and cultural activities for over 14,000 students in over 28 schools in Guatemala. In Iraq, over 38,600 adolescents and youth have benefitted from mentorship, and other forms of support since 2016. An estimated 52% of the beneficiaries in Iraq were females (Mercy Corps, 2021).

However, population dynamics in the next forty (40) years may address some of the high unemployment challenges currently witnessed in many developing economies. Data shared by Jones (2020) revealed, the global working-age population is expected to witness 10% decrease by 2060. On individual country basis, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Greece, Japan and Korea are projected to witness 35% or more reduction in their respective working-age populations during the period.

Conversely, countries such Australia and Mexico are expected record over 20% increase in their respective active work force. The working-age population in Israel is projected to surge by 67% by 2060, citing high fertility rate comparable to the “baby boomers” generation in the United States of America as the reason for the sporadic increase. Some economies could leverage on their relatively high working-age population by exporting human capital to other countries; or by maintaining the working population to attract foreign direct investments.

The expected changes in population demographics are likely to result in capital flights across countries and regions. Jones (2020) noted, the expected changes in the world’s demographics by 2060 are likely to induce capital flights from economies with ageing population to economies characterised by youthful population and significant number of active labour force. Another derived effect from the changes in demographics is global redistribution of economic power.

Perspectives on Youth Unemployment Challenges in Ghana

The decision to encourage entrepreneurship among the youth would come with myriad of benefits, including youth entrepreneurship serving as breeding ground for future successful businessmen and women; and creating the enabling environment for the Ghanaian economy to harness large domestic investment funds in the medium- and long-term with relative ease, thereby reducing extensive reliance on foreign-investor participation in the domestic economy.

Other benefits include helping to improve the socio-economic livelihood of Ghanaian youth who would in turn, remit their parents; and provide the needed financial assistance for their siblings, close and distant relations and friends. Thus, successful youth entrepreneurship does not only assure improvement in the livelihood of young people identified for the programme, but also improvement in the lives of their significant relations and others.

In 2017, the President Nana Addo Dankwah Akufo-Addo-led government introduced the Free Senior High School (Free SHS) policy and programme for implementation in Ghana. The underlying objective of this policy and its attendant implementation was to ensure every Ghanaian child gains access to secondary education and that, funding should not be the barrier to entry into second cycle institutions by graduates from the Junior High School (JHS) level.

The socio-economic benefits of the novel programme are manifold: it extends the academic life of young people beyond JHS level; increases tuition affordability which reduces early school drop-out rates; elected governments have “ample” time to plan and put the necessary structures and measures in place to absorb the country’s labour force in the job market at a future date; extended academic life of young people is likely to enhance the quality of human capital churned out to the national, sub-regional, regional and global labour markets; competitiveness of Ghana’s skilled human capital in the world labour market is likely to be improved; and the standards of living of young people who graduate from the tertiary institutions are likely to improve, among other positives.

The presumption is, trained human capital in Ghana for both local and international labour markets would be dominated by graduates from tertiary institutions; and not from lower levels of the academic echelon.

Presently, there are about sixty-four (64) accredited private and nineteen (19) public tertiary institutions in Ghana. On the average, each of these tertiary institutions graduates about three thousand (3,000) students annually. This implies about two hundred and forty-nine thousand (249,000) (3,000 x 83 tertiary institutions = 249,000 graduates) tertiary-level learners are trained and graduated annually for the job market. This estimation (249,000 graduates) is slightly in excess of the figure (230,000 new entrants) quoted by Hoetu (2015, p. 1), but reflects increases in enrollment and graduation rates at the tertiary level in recent years.

Further, what is certain is the population of new entrants is in excess of the cumulative number of employees who retire from both the public and private sectors of the Ghanaian economy annually. Since the youth entrepreneurial initiative is at its nascent stage, elected governments are saddled with how to effectively address the youth unemployment challenges in the country.

Juneja (n.d.d) argued, the youth constitute the future human capital of every economy. Therefore, their development must remain a priority just as financial status, economic position and availability of natural resources remain top-most priority to leaders across global economies.

However, the author asserted, development of the youth to be resourceful and innovative future generation remains a shared responsibility; the collective efforts of government, industry, academic institutions, community, society and family are required to achieve this feat; each of these stakeholders has unique and interdependent role to play towards transformation of “ordinary youth” into resourceful and successful young entrepreneurs; and productive future human capital.

In the United States of America, the foregoing statement is amply demonstrated in the convergence of hundreds of youth through entrepreneurship in Silicon Valley and in other parts of the country.

The education system in Ghana and in many other developing economies train and prepare students for the job markets rather than consider the establishment of businesses as primary objectives. Most instructors at the tertiary level are noted for adapting phrases such as: “As you go into the competitive professional world…” in the course of imparting knowledge during learning sessions.

These statements draw the potential graduate’s attention to the competitiveness of the global job market and how he or she should be psychologically and professionally conditioned to have an urge over other competing job-seekers with minimal emphasis on entrepreneurship. This results in excess supply of youth labour over demand, as the job market is inundated and saturated with more human capital than it could absorb.

However, a report released by the World Bank in 2018 noted, the quality and competitiveness of human capital trained in Ghana through the current education system are weak. The report undermined the qualitative and quantitative usefulness of the prevailing system of education and the urgent need for its replacement since it has been reviewed and re-experimented severally without better outcomes.

Juneja (n.d.d) shared, the historical antecedent of American tradition and culture supports individual creativity and youth entrepreneurship. The cultural dynamics of the United States allow young persons to explore, make mistakes and be pardoned, learn from prior mistakes and emerge as more refined and productive. Conversely, the European culture, especially the prevailing culture in the United Kingdom, encourages young people to take up or apply for jobs other than strive to be self-employed. This cultural “syndrome” is passed on from one generation to the other.

Ghana was a British colony and Ghanaians were traditionally indoctrinated with the search for white-collar jobs to the detriment of aspiring to be self-employed. This approach or cultural indoctrination had no strong negative effect on the country’s total labour force in the early years of independence when the population was relatively small (about 6 million people as of 1960).

However, with the geometric increase in national population, especially youth population in recent years, relative to the arithmetic increase in development of economic structures and job creation to accommodate the fairly large youth population, reliance on the white-collar job approach bequeathed to the nation by the British is becoming socio-economically irrelevant.

The test of contemporary times requires strategic thinking to realign the nation’s labour force with her job opportunities. Hence, the need to develop vigorously youth entrepreneurial programmes that could be nursed into large ventures to assure continuity in business development by the youth during adulthood.

Over the years, Orthodox Churches, including the Roman Catholic, Presbyterian, Methodist, Anglican, Evangelical Presbyterian (E.P.), Global Evangelical Presbyterian, African Methodist Episcopal (A.M.E.) Zion, among others; Pentecostals comprising the Church of Pentecost, Assemblies of God, Apostolic, Kristo Asafo, Christ Apostolic; and Charismatics such as the International Central Gospel Church (ICGC), Action Chapel, and Perez Chapel, to mention, but a few, have contributed significantly to the training and development of human resource professionals by establishing academic institutions at various levels including basic, secondary and tertiary across the country.

Further, leaders of the Islamic faith have established academic institutions at various levels, including tertiary, in different parts of the country as their contribution to the development of human capital.

The foregoing implies religious institutions contribute directly and indirectly to the relatively high annual tertiary students’ graduation rate recorded in the country. Indeed, the enormous efforts of these religious bodies at churning out productive human capital for effective development and growth of the Ghanaian economy are duly acknowledged. However, unemployment remains a major threat to the Ghanaian economy.

Earlier unemployment statistics released by the International Labour Organisation for 2019 pegged Ghana’s respective general and youth unemployment rates at 6.78% and 13.69%. The respective general and youth unemployment rates for 2018 were 6.71% and 13.70%. Indeed, the data showed relatively low unemployment rates during the periods under consideration; and seemed to suggest the existence of fairly low unemployment challenges in the Ghanaian economy.

To buttress the foregoing argument, Ghana’s unemployment rates compared favourably against rates recorded by South Africa, Nigeria and France during the period. However, some economic pundits argued the rates do not reflect the actual number of unemployed in the Ghanaian economy. Further, the percentages are not a true reflection of unemployment challenges in the country due to a number of factors, including the absence of accurate measurement and reliable data on Ghana’s youth and general labour force; and its attendant socio-economic dynamics, among other pertinent factors.

These arguments were relevant to the research which sought inter alia, to assess the implications of youth unemployment rate for general unemployment rate with the Ghanaian economy serving as the unit of analysis during the study period.

Rather than emphasising on youth unemployment rates, elected governments and other key stakeholders including religious institutions would be better-off focusing their attention on how to strategically address the youth unemployment challenges through significant reduction in the total number of young people that remain unemployed.

To mitigate the foregoing issues, religious bodies are being called upon to complement government’s efforts by participating actively in the One District, One Factory initiative. The various religious bodies are solemnly called upon to draw on the spiritual and scientific discernment that culminated in their establishment of academic institutions at various levels to consider the establishment of more businesses to assist the country in addressing the growing youth unemployment conundrum.

Stated differently, religious institutions in the Ghanaian economy are entreated to consider strongly, the establishment of factories in strategic parts of the country to boost the nation’s industrialisation drive, shore up the youth employment rate, improve on the level of job expectations among young graduates; and to enhance Ghana’s competitiveness at the sub-regional, regional, and global levels.

Undoubtedly, the establishment of more factories would contribute to significant reduction in total imports to appreciable levels. This would improve the nation’s balance of payments through excess valuable exports over imports; ensure relative stability of the local currency (Ghana cedi) against major foreign currencies such as the British pound sterling, American dollar, and the European euro, among others.

Although churches in Ghana and across the world are noted for their humanitarian gestures, little is known about the Churches’ direct and significant involvement in the establishment of factories as a means of helping governments to alleviate challenges related to high youth and general unemployment rates. Throughout the world, most churches are noted for growing crops to meet the growing food needs of increasing populations; and establishing administrative offices as well as radio and television stations in furtherance of the gospel and winning souls.

The decision of religious bodies in Ghana to heed to this humble appeal and establish factories in selected regions and districts across the country may be an economic novelty; it may be an economic theory that would be tested, later proven and accepted in other economies just as microfinance was started in Bangladesh, and now remains an economic model worthy of emulation and application in many developing and emerging economies, including Ghana.

The cultivation of farm lands and variety of crops in commercial sizes and quantities; and the establishment of technological “hub” by Kristo Asafo for manufacturing of cars, equipment, and detergents, among others in Ghana, are worth-commending. Further, the establishment of major hospitals by the Catholic Church to readily absorb nurses trained by the Catholic Nursing Training College and other nursing training colleges in strategic parts of the country deserves special mention.

Finally, establishment of the erstwhile Capital Bank by the ICGC was a prototype; it was a strategic way of absorbing trained young graduates from the Central University and other tertiary institutions across the country in the job market. However, such sterling initiatives require improved and sustainable management acumen to assure continuity or extended corporate life span.

The one district, one factory programme presents unique opportunity for religious institutions in the country to be global pace setters in the collective fight against high youth unemployment and under-employment rates; assure prosperity for the nation’s future human capital; and to play integral role in restructuring and acceleration of robust and resilient Ghanaian economy in post-COVID-19 era.

Author’s Note

The above write-up was extracted from recent Publication on “Youth entrepreneurship: Essential tool for socio-economic development and growth” by Ashley, Tufuor, Obeng, Agbenuvor and Ackah (2024) in the International Journal of Business and Management (IJBM). DOI No.: 10.24940/theijbm/2024/v12/i2/BM2402-015