At the end of October 1957, William Arthur Lewis arrived in Ghana at the request of Kwame Nkrumah to take up the position of Economic Adviser to the Government of Ghana. On 4th November, Nkrumah wrote to Lewis saying that the most important task to be carried out in time was “stock-taking of our entire economic and financial policy”.

Today, we expect that Ghana’s economic conditions in 2023 will be more difficult than those experienced in the past 12 months. For this reason, “taking stock” will require an honest assessment of the country’s resources, needs and expenditures. This need for an honest assessment would be familiar to William Arthur Lewis – the economist and public figure born just over a century ago on 23rd January 1915.

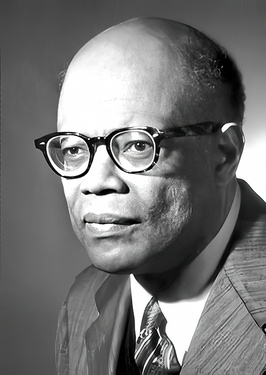

In his career, Sir William achieved several firsts which helped break racial barriers; demonstrating exceptional achievement against accepted (and persistent) discrimination. He was the first faculty member of West Indian origin at the London School of Economics, and at the University of Manchester became Britain’s first West Indian professor and later the first Black faculty member at Princeton University. He was also the first Nobel laureate of West Indian origin in any field, and the only Black recipient to date of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Science.

Lewis, the fourth of five sons, was born in the British West Indies to parents, both teachers, who had migrated from Antigua about twelve years before. He died in 1991.

Lewis was raised by his mother, Ida, from the age of seven when his father died. At fourteen William joined the civil service; learning, he said, “to write, to type, to file and to be orderly”. Three years later he gained a scholarship to the LSE, where he won the Director’s Prize for best undergraduate essay. He graduated in 1937 with first-class honours and joined the LSE’s PhD programme.

Having completed his doctorate at twenty-five, Lewis taught at the LSE between 1938 and 1948 before taking up the prestigious Stanley Jevons Professorship of Political Economy at the University of Manchester on J.R. Hicks’ retirement. There, his pivotal work on development economics began. In 1947, the Colonial Development Corporation (now British International Investment) was created – and in 1951 Lewis joined its board, under Lord Reith’s chairmanship. Lewis’s biographer, the late Robert Tignor, tells us that he had long worked closely with the Colonial Office, and partly on this basis published in 1955 one of his most widely-read books, The Theory of Economic Growth.

Between 1957 and 1963, as well as being Economic Adviser to Nkrumah, Lewis became in turn Deputy Managing Director of the United Nations’ Special Fund; a director of the Central Bank of Jamaica; the first West Indian Principal of the University College of the West Indies; and the first Vice-Chancellor of the University of West Indies, after it set up its second campus at St Augustine. From 1963 until his death in 1991, he occupied the James Madison Professorial Chair of Political Economy at Princeton University, and concurrently the presidency of the Caribbean Development Bank (1970-1974). In 1978, Lewis was knighted and in 1979 received the Nobel Prize. In 1982, he was appointed President of the American Economics Association.

Lewis first travelled to Britain in 1933, a time of recession and intellectual excitement. The country was searching for ways to end the heavy unemployment brought on by the depression. The economic system then, as now, was seen as failing to deliver prosperity and being assailed from different quarters. J.M. Keynes, based at King’s College Cambridge, and his school had discussed combining loan-financed public works to help raise incomes and improve the trade balance, so as to turn a greater proportion of domestic expenditure into domestic income. These views contrasted sharply with the LSE’s Friedrich Hayek and Lionel Robbins, who had misgivings about government intervention in the economy. Against this background, Lewis published one of his better-recognised works, The Principles of Economic Planning.

Toward the end of World War II, Lewis began lecturing on questions associated with causes of the great depression, the role played in international relations by international trade, and the factors that impeded trade. This work heralded his lifelong interest in international economic history. Between 1949 and 1954, his study of colonial agriculture, industrial development and land settlement underlied his seminal ‘Economic Development with Unlimited Supplies of Labour on growth’ of 1954. This work has been described as “the single most influential article in the history of the field of development economics” and was acknowledged by the Nobel Committee.

In 1984, writing for a World Bank collection, Lewis reflected on the issues that preoccupied him in the 1950s: such as how the modernisation of countries was to be financed. Today, when countries like Ghana have lost access to the international capital markets, this question is pressing. The IMF’s outlook for the coming year prompts apprehension of an even broader incidence of sovereign debt defaults. The distressed status of domestic local currency debt in Ghana claims attention here.

About a decade ago, a ground-breaking article by Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff warned that when defaults on domestic debt occur, they tend to accompany greater distress than defaults which occur on external debt alone. Lewis’s work on debt reminds us that sovereign loans are justified only if they are “invested economically”, by which he meant that “the loan must add more to national income than it costs”; and that “enough of this extra income accrues within the lifetime of the loan – i.e. that one is not borrowing on short-term to finance long-term investment”. This is advice well worth bearing in mind as future borrowing plans come under scrutiny in upcoming debt restructuring negotiations.

A less well-known work by Lewis, ‘Politics in West Africa’, although written about the 1950s, impacts more broadly on our understanding of several issues that relate to any emerging market’s economy. Lewis’s primary concern in writing was the emergence in Africa and elsewhere of “one-party states”, banning or absorbing all opposition. Since then, emerging markets worldwide, including Ghana, have generally accepted democratic forms of governance.

Nevertheless, Lewis’s work is prescient in its concern with the importance of accountability to societies. Acknowledging that countries aren’t governed by angels, Lewis reasoned that “for a principle to find a great leader who is himself a man of principle is almost a happy accident … not very likely except in a political framework [sustaining] high standards of political behaviour”. Hence, Lewis writes that he saw the history of democracy as showing “the efforts good men make to hold bad men in check”. The process of regaining the confidence of international capital markets involves building institutions which keep “bad policies” in check and can be tortuous.

Historically, countries that default have tended to regain access to capital markets, under certain conditions. When default occurs because of exogenous shocks alone, countries are more likely to regain market access simply on their intact reputation for sound economic and social policies and strong institutions. Naturally, this all depends on global liquidity. The higher the yields on instruments like US Treasuries, the less likely investors are to lend to emerging markets – like Ghana.

The prospect of a debt crisis continuing to face Ghana highlights the task of fiscal policy and strong institutions. To renew the access to financial markets, creditors expect fiscal responsibility legislation to restrain a government’s discretion to increase spending when the markets find its debt too high, particularly where a deficit bias exists. Some debt-distressed countries have fiscal responsibility legislation that contains escape clauses by which the rules can be suspended at the government’s discretion. This is true of Ghana’s legislation, and it should be reassessed.

One solution is independent fiscal councils which have a statutory duty to evaluate a government’s “fiscal policies, plans and performance against macroeconomic objectives relating to the long-term sustainability of public finances, short-medium-term macroeconomic stability, and other official objectives” (International Monetary Fund). The introduction of these independent institutions would usefully underpin restructuring of the country’s debt.

Of equal importance is the political stability that accompanies a broad consensus to take difficult decisions. In this context, it is worth remembering that Lewis opposed a ‘winner-takes-all’ form of democracy: he preferred political institutions “which give all the various groups the opportunity to participate in decision-making”. This is particularly important when political parties must navigate their countries out of debt crises through difficult austerity programmes requiring political consensus beyond party lines, as a necessary step in regaining access to the capital markets.

In a letter dated 18th December 1958, ahead of his resignation as an adviser, Lewis wrote to Nkrumah setting out the areas of disagreement between them. At the heart of Lewis’s disappointment was that his meticulous estimates of which expenditures were wise, feasible and worthy of inclusion in government expenditure plans were ignored by Nkrumah and his ministers, who instead advocated higher expenditures and the approval of unproductive projects.

Nkrumah’s response to Lewis’s letter sums up his government’s attitude to the underlying causes of Ghana’s financial decline. Nkrumah wrote, “The advice you have given me, sound though it may be, is essentially from the economic point of view; and I have told you on many occasions that I cannot always follow this advice as I am a politician and must gamble on the future”. In many respects, Nkrumah’s reluctance to follow what he recognised as sound economic advice says it all.

Following his appointment as President of the Ghana Economic Society, Lewis delivered a Presidential Address that was published in 1959, in which he reasoned: “It is essential to the working of democracy that there shall be a lively and critical discussion of any programme submitted by any government”.

Commenting on this viewpoint, Dr. Jonathan Frimpong-Ansah who, like Lewis, was a graduate of the LSE, and became Deputy Governor of the Bank of Ghana (1965-68) under the Nkrumah government and went on to become Governor (1968 to 1973), deduced that: “Lewis saw the greatest danger as that posed by the complete lack of public opinion to enable independent assessment of development strategy”. Frimpong-Ansah argued that at the time, “there was general political autocracy surrounding the preparation and implementation of [economic plans] and … governments were praised for whatever they did, and progress appraisals were often inaccurate because they were generally assessed by what had been spent and not what had been achieved”. This situation agitated the mind of Lewis and was as important to avoid then as it is today.

Ghana, along with other debt-distressed countries, will progress by working within democratic structures. These countries must strengthen fiscal frameworks and other institutions if their citizens are to continue building confidence in democratic government and return to investment in domestic government debt, or make capital available to private industry through domestic banking systems. This is essential, for as Lewis reminds us “countries grow fastest whose citizens think it is safe to save and invest at home”.

The author is at King’s College, Cambridge, and is a Research Associate at Cambridge’s Centre for Financial History.