This article discusses Ghana’s Double Tax Agreements (DTA) with other countries, and examines issues of treaty shopping and low withholding tax rates in these DTAs, necessitating the need for review and renegotiation of some of the existing DTAs.

Ghana has signed DTAs with about eighteen sovereign states; however, only twelve of these bilateral tax conventions are currently in force. The countries with which Ghana’s tax treaties are currently in force are the United Kingdom, Belgium, Italy, South Africa, Switzerland, Netherland, France, Germany, Mauritius, Singapore, Denmark and Czech Republic.

Agreements for avoidance of double taxation or tax treaties are concluded with the principal purpose of promoting exchange of goods and services, and the movement of resources (capital resources as well as persons) by eliminating international double taxation.

There are three key ways that DTAs can restrict a country’s ability to tax foreign investors. First, by lowering the rate of withholding tax levied on foreign income earned at source. Second, by imposing a high threshold for permanent establishment; that is the minimum level of activity that must take place before taxes can be levied. Finally, tax treaties may simply exempt some types of income earned in the source state from taxation in that state[1].

The legal basis of double tax treaties in Ghana

Tax treaties globally derive their legal status from the Vienna Convention on Law of Treaties which

provide that every treaty in force is binding upon the parties to it, and must be performed by them in good faith.[2]

The 1992 Constitution of Ghana provides the legal basis for treaties in Ghana[3]. The President of the Republic is responsible for the execution of treaties and conventions. The treaties, so executed, are subject to ratification by Parliament of Ghana by way of resolution of Parliament, supported by the votes of more than one-half of the Members of Parliament. Once ratified by Parliament, the Government of Ghana notifies the other contracting state for the coming into force of the treaty. The other contracting party is also required to notify Ghana, through its Diplomatic Mission post in that country of the completion of procedures required for coming into force of the treaty. Upon completion of these processes, the treaty would ordinarily come into force on 1st January of the year following the year of ratification and notification. All provisions of the tax treaties override domestic laws in Ghana, not just at the date of signature, but as long as the treaty remains in force.

Termination of tax treaties

All tax treaties signed by Ghana continue in force until terminated by either contracting state. Each contracting state desiring to terminate a tax treaty shall communicate its intentions to terminate to the other contracting parties through the diplomatic mission by giving at least six months’ notice. In practice, this is usually done after the treaty has been in force for at least five years.

In case a treaty is terminated, the treaty ceases to have effect in the respective fiscal year immediately following the one the notice of termination was given, and the relevant domestic laws of the countries become applicable again to taxation of income. Ghana has not yet terminated any of its tax treaties.

Origin of Treaty Shopping and Low Withholding tax rates

Taxation of fiscal jurisdictions in the traditional market territory relies on one of two principles or a hybrid of both – the principle of source or the principle of residence-based taxation.

Tax treaties stipulate which of the two principles should prevail when they come into conflict: principle of source, by which a country is entitled to tax income because it is earned within its borders; and the principle of residence, by which a country is entitled to tax income because it is earned by one of its residents. The principle of residence privileges the taxing rights of the net capital-exporter in the relationship while the principle of source privileges those of the net capital-importer. The countries in such a relationship are, therefore, often referred to as the residence and source countries respectively.

Both the OECD and (to a lesser extent) the UN Models favour the residence principle, where tax residents of a country are subject to taxation on their worldwide income, and a greater portion of taxation rights are allocated to a residence country.[4] DTAs thereby shift taxing rights from the source state (capital-importing country) to the residence state (capital – exporting country).

Limitation of benefit provisions in Ghana’s tax treaties

The Revenue Administration Act, 2016 (Act 915) has a general ‘limitation of benefits’ rule which specifically denies tax treaty benefits to companies whose underlying owners are not mostly residents of the treaty partner.[5] The exemption from or reduction of tax per the tax treaties is not available to an entity that: for the purpose of the arrangement, is a resident of the other contracting State; and fifty percent or more of whose underlying ownership is held by persons who, for the purpose of the arrangement, are not residents of the other contracting State or Ghana.

The limitations of benefits provisions in most of Ghana’s old tax treaties are restricted to only dividends[6], interest,[7] royalties and management services, and do not apply to the tax treaty as a whole. Hence, Treaty Shopping is possible under other articles such as the Permanent Establishment (PE) article or especially the capital gains article.

Low withholding tax rates in Ghana’s tax treaties

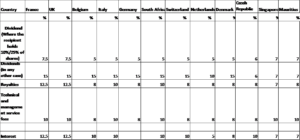

Tax treaties set maximum rates at which withholding taxes can be levied on cross-border payments, specifically dividends, interest, royalties and management or technical service fees. The Income Tax Act, 2015 (Act 896) as amended, provides that withholding tax on dividends is 8 percent, interest is 8 percent, royalties is 15 percent, and management and technical services if performed by a non-resident entity is taxed at 20 percent.[8] Services, if performed by Ghanaian resident entity, are subject to tax at 7.5 percent. However, as provided in table 1, these payments are subject to lower withholding tax rates as per the provisions of Ghana’s DTAs.[9] Withholding tax rates per Ghana’s tax treaties compared to the rates provided in the Ghana Income Tax Act[10] on all these types of payments gives an indication of the revenue foregone as a result of the reduced withholding tax rates on dividend, management fees and interest stipulated by the tax treaties.

Treaty tax rates

Tax rates applicable under the terms of these tax treaties are as follows:

No withholding tax on imported services provided by companies other than individuals in Ghana-Switzerland Tax Treaty.

The Ghana-Switzerland DTA, under article 12 (4), is for purposes of withholding tax on royalties and services. The definition of services under this article provides for no withholding tax on services provided by a resident entity in another party’s state unless such a services is provided by an individual, and not a company. Hence, if a non-resident entity other than an individual from Switzerland provides services in Ghana, such a service will not be subjected to withholding tax.[11]

Permanent establishment provisions in Ghana’s tax treaties

Provisions on permanent establishment (PE) in most of Ghana’s tax treaties generally provide for a fixed term of a business through which the business of an enterprise is wholly or partly carried out, except for Ghana-Mauritius and Ghana-Singapore tax treaties. No specific provisions for services permanent establishment is provided in Ghana’s tax treaties with other states currently in force.

In addition, the Ghana-Netherland, Ghana-Switzealand, Ghana-Denmark and Ghana-Germany bilateral, and Ghana-Czech Republic tax treaties further provide for construction of permanent establishment. The building, assembling, installation or supervisory activities constitute permanent establishment only if it lasts more than nine months. However, Ghana’s other tax treaties provide for 183 days or six months to trigger a permanent establishment. Moreover, Ghana’s Income Tax Act also provides for services of permanent establishment, requiring a period of at least six months to trigger services of permanent establishment which is in conflict with the provisions of some of Ghana’s double tax treaties on permanent establishment, except for Ghana-Czech Republic and Ghana-Singapore DTAs, and to the extent of the inconsistency the provisions of the tax treaties shall prevail. [12] Other countries’ tax treaties, such as Netherland-Ethiopia tax treaty, have six months for permanent establishment to kick in for construction PE.[13] The tax treaty between Netherland and Zambia provides for 183 for construction PE and also 183 for service PE. [14]

OECD Multilateral Convention to implement tax treaty related measures to prevent base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS Action 7)

Tax treaties generally provide that business profits of a foreign enterprise are taxable in a jurisdiction only to the extent that the enterprise has in that jurisdiction a permanent establishment to which the profits are attributable.[15] The definition of permanent establishment included in tax treaties is, therefore, crucial in determining whether non-resident enterprises must pay income tax in another jurisdiction. BEPS Action 7 proposes several changes to the definition of permanent establishment in the OECD Model Tax Convention to counter BEPS. Ghana, as at 6th October, 2022, was not a signatory to the Multilateral Convention to implement tax treaty related measures to prevent base erosion and profit shifting.[16] So far, 100 countries globally, including 13 African countries, are signatories to this convention. The African countries which are signatories to this Multilateral Convention are Burkina Faso, Cameroun, Côte d’Ivoire, Egypt, Gabon, Kenya, Mauritius, Morocco, Nigeria, Senegal, Lesotho, South Africa and Tunisia.

Recommendation

To address the challenges of tax treaty shopping and lower withholding tax provisions in the Ghana’s tax treaties, the following suggestions are proposed for governmental authorities;

-

Conduct stakeholder consultations based on draft negotiation texts. Urgently reconsider the treaties that most restrict the tax rights of Ghana.

-

Introduce general ‘limitation of benefit’ provisions that apply to all articles of future bilateral tax treaties and provisions that can provide important protection as it limits reduced withholding rates and other treaty provisions to apply only to companies that meet specific tests of having some genuine presence in the treaty country.

-

Identify the areas where the tax treaty and domestic legislation leave it most vulnerable to revenue loss. This includes PE definition (treaty and domestic), treaty shopping (treaty and domestic), and withholding taxes (treaty).

-

Request renegotiation of treaties that have the greatest actual cost. These renegotiations should be conducted on the basis of an improved distribution of the taxing rights in Ghana’s favour, not a balanced negotiation.