Abstract

The causes and consequences of begging are well known but workable solutions are elusive. So far legislation against begging, livelihood support programs and other macro level interventions have failed to yield any significant results. This exploratory study investigated the nature of begging in the Nima Community, the perspective of community leaders about the problem and crucially the role of community leaders in addressing the problem.

A single case study design was used for the study. Primary data was obtained from beggars and community leaders in Nima, an inner city inhabited predominantly by immigrants and Muslims in Accra. Questionnaires and interviews were employed for data collection from conveniently sampled beggars and purposively sampled community leaders respectively. Combining thematic analysis and simple descriptive analysis, the study revealed that begging in Nima is nuanced.

The beggars are demographically diverse, they include Ghanaians and international emigrants and they employ active begging and passive begging techniques. Community leaders in Nima are incensed and appalled at the prevalence of begging in their community, but they also take the view that many of the beggars are ‘outsiders’.

Although leaders recognize the centrality of their role in addressing begging, they have failed to demonstrate sufficient capacity to address the problem. The study concludes that it is imperative for leaders to be collaborate in finding innovative solutions to the problem of begging because communities are complex adaptive systems. It is recommended that any approach taken must be inclusive and participatory; giving beggars the opportunity to partake in their redemption.

Introduction

Poverty is widespread in Ghana, but it is more prevalent in some areas and among some communities than others. Muslim communities, especially ‘Zongos’ are among the very poor communities in Ghana (Weiss, 2007) and Nima in Accra is no Exception.

The low economic status of inhabitants of Zongos is manifested in the low level of education and poor standard of living in these communities, a situation which has forced paupers in Zongos to beg for alms around mosques and other public places. However, begging a dimensional social menace and no single factor explain the phenomenon adequately.

Focusing on Nima, a community in Ghana, this study assesses the menace of begging at the micro level and takes the view that effective grassroots leadership is essential for addressing the menace. The paper begins with an introduction which explores the dimensional nature of begging and also why it is a developmental problem in Ghana. This is followed by a review of extant empirical literature and then the theoretical underpinnings of the study. Subsequently, the research methodology is outlined and findings and discussions are presented leading to final of part the paper, conclusion.

In many developing countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, children, women and physically challenged people survive through street begging because the welfare system in these countries is either weak or entirely non-existent (Kaushik, 2014). Incidents of begging are also quite high in predominantly Islamic suburbs due in part to the tolerance of begging in Islamic religion (Osa-Edoh & Ayano, 2012; Tambawal, 2012). There are also counter arguments that begging is not an Islam induced problem because Islamic religion does not endorse begging in principle (Ogukan, 2011). It suffices that aside being a social practice with religious undertones, begging is also a consequence of social structuration and state inaction.

Begging in Ghana, is a major problem that has drawn national attention including the enactment of legislation that proscribes begging (Weiss, 2007). Nevertheless, begging for alms is still a common sight on busy streets, market centres and around mosques. In Ghanaian culture, hard work is highly esteemed, therefore begging as form of living is not encouraged and may bring disgrace to oneself and family. In the light of this, beggars are often looked down upon, considered among the wretched and given very low social status (Smith-Asante & Awiah 2015).

Several attempts have been made at addressing the menace of begging in Ghana but to no avail. Reflecting on interventions aimed at addressing begging, Groce, Loeb and Murray (2014) observed that criminalizing and arresting beggars has not worked in any society. Programs to provide beggars with alternative livelihood have been successful in some countries, but only to an extent as these are macro level interventions that are usually too expensive to sustain. A lot of strategies have been tried except community level action led by community leaders.

Martiskainen, (2016) opines that community leadership which thrives on social capital and volunteering is much powerful for causing change at the micro level. Notwithstanding, research effort directed at finding solutions to begging in society has failed to explore how the menace can be addressed at the community level through effective leadership. As a result, the purpose of this study is to assess how the menace of begging can be addressed at the grassroots level through effective leadership. In line with this purpose the study specifically explores the nature of begging in Nima, it also examines the perspectives of community leaders about the begging and further investigates how community leaders can help address the problem of begging.

Review of Literature

Nature and Typologies of Begging

Begging means asking for something; food, money or whatever it may be. It does not matter whether one pleads, employs persuasion, or put oneself in a position to receive a favour that does not have to be reciprocated, it is still begging (Kothari, 2011). For Clark (2007), begging is simply the antithesis of work. Begging refers to living in laziness at the expense of other people. However, Clark (2007) links begging to the structure of the state which places some individuals at advantageous positions over others. Thus begging becomes a political and economic consequence of societal structure and actions and hence a developmental concern.

The exponential increase in the number of beggars continues to haunt sociologists, geographers and urban planners (Fawole, Ogunkan & Omoruan, 2011; Weiss, 2007). In Ghana, it is common to see beggars who are mostly physically challenge moving from vehicle to vehicle in busy urban streets pleading for mercy and begging for alms (Smith-Asante & Awiah, 2015). There are also many people begging on the streets, in cities, local communities and around places of worship such as Mosques (Weiss, 2007).

In an attempt to fashion a taxonomy for street beggars, Namwata, Mgabo and Dimoso (2012) posit that street beggars can be classified as beggars of the street, beggars on the street, beggars in the street and beggars of street families. On his part, Saeed (2011) draws a distinction between religious and circular beggars. In some religions (Hinduism, Sufi Islam, Buddhism, and Jainism), begging is an accepted form of support for particular sections of adherents. People might also be pushed into begging for a living as a result of social, political and economic reasons; this is referred to as circular begging.

Dynamics of begging as a social menace

Beggars constitute a social threat to societies especially in cities. The number of beggars continues to swell and the theatrics beggars employ continues to improve. Organised begging particularly is on the increase in many countries because of immigration and increased social inequality (Namwata, Mgabo & Dimso, 2012).

This form of begging used to be prevalent in European countries where immigrants and refugees live on streets virtually begging to irk a living. However, it is fast becoming a trend in Ghana and other African countries because of irregular migration in the sub-region (Benattia, Armitano & Robinson, 2015).

Begging is a prevalent problem in predominantly Muslim communities. This situation has led many to associate Islamic religion with begging, some researchers (Osa-Edoh & Ayano, 2012; Tambawal, 2012) even finger Islam as fuelling the prevalence of begging in society. This is because charity or the obligation to provide for other people less fortunate in society is a fundamental concept of many religions including Islam.

Muslims are familiar with several charitable practices but the prominent ones are; Zakat (obligatory giving of alms), Sadaqa (voluntary giving of alms) and Waaf (pious endowment that may serve a charitable purpose). Begging may even take the form of exchange of service for Quranic education (Emmett, 2001).

The act of begging is considered a menace in many societies because it contradicts societal values and norms (Sewanu, 2014). Begging in public spaces is also unsightly as beggars portray negative images to visitors and outsiders owing to the gross appearance some of them carry and the theatrical styles they employ to persuade the public into giving. Nevertheless, beggars continue to parade at city centres, around busy streets and other public places.

In Ghana, beggars even migrate from Northern to Southern parts of the country because of the concentration of cities and economic activities in these areas. Some beggars are also emigrate from neighbouring and distant African countries (Niger, Mali) to Ghana especially Accra. These beggars as mostly not employable or have refused to find any meaningful work under the pretext their physical or economic predicaments (Weiss, 2007).

Addressing the menace of begging in Ghana

Certain kinds of beggars can be arrested and prosecuted in Ghana. However, the law only criminalise certain kinds of abusive and forceful begging in public places whilst living a caveat for the continuation of other kinds of begging in a religious or cultural form.

The Beggars and destitute ACT-1969 (NLCD 392) makes begging a criminal offense in Ghana, but article 2 of the ACT stipulates that “A person shall not be deemed to be begging by reason only of soliciting or receiving alms in accordance with a religious custom or the custom of a community or for a public charitable purpose or organised entertainment”. Criminalizing begging may be effective in some cases but the outcomes of zero tolerance of begging can also be negative as some beggars might respond to enforcement in with devastation (Johnsen & Fitzpatrick, 2008).

Addressing begging (of religious nature) in a circular state that guarantees the freedoms of worship and association can be troubling. It is even more difficult when child beggars are involved as many of them beg to support themselves and their families (Owusu-Sekyere, Jengre & Alhassan, 2018). Weiss (2007) suggest the creation of enabling conditions that encourage discerning religious life under modern conditions. For example, there should be opportunities for religiously oriented mobilisation that combines individual salvation and commitment to community welfare which are both important principles in Islam.

Other approaches have also been taken such as ensuing social inclusiveness. Ghana’s National Social Protection Strategy (NSPS) concentrates on social risk reduction and on addressing the dynamics of poverty (Weiss, 2007). This is typified by the Livelihood Empowerment Against Poverty (LEAP) and Social Grants Program which seek to attain their goals by committing to human capital investments, improved law enforcement (labour law), distributing social grants and ensuring the protection of informal sector workers (UNDP Human Development report, 2007). In spite of these advances, begging still prevails in Ghana because of the cultural, religious and socio-economic dynamics.

Community Leadership

Leadership is concerned with setting and achieving goals with followers, it entails showing followers the right way to go, but it involves influence rather than authority (Sharma & Jain 2013). Leadership may also be conceptualised as a group of behaviours, expertise or skills (Amanchukwu, Stanley & Ololube 2015).

Community leaders in many localities play a crucial role as change agents because they wield significant authority and influence over the inhabitants in their communities (Tieleman & Uitermark, 2018). Community leadership is distinct from classical concept of leadership which entails leaders influencing and persuading followers.

Characteristically, community leadership involves the creation of social capital and is less hierarchical. Community leadership is also usually a non-elective position, often informal, nevertheless, community leaders are symbolisms of change in their localities (Martiskainen, 2016).

In many African communities including Ghana community leaders include traditional leaders, clergy, political activists, teachers and merchants. Community leadership which thrives on social capital and volunteering is much powerful for causing change at the micro level (Martiskainen, 2016). These individuals or categories of people are committed to local development and work together to find solutions to community problems. Stemming from this, community leaders have the potential to find solutions to begging.

Theory

Complexity leadership theory is one of the theories that has emerged strongly for explaining the changing nature of leadership in a society that is growing more complex each day. Under this theory, leadership is viewed as interactive and dynamic but above all complex process that facilitates the emergence of learning, innovation and adaptability as outcomes (Baltaci & Balci, 2017). Complexity leadership theory stresses the non-linearity of leadership and moves the discourse on leadership from the actions of heroic individuals to social context where influence is very important.

Complexity leadership theory postulates that leadership consists of three interacting roles: administrative, adaptive, and enabling (Uhl-Bien, Marion & McKelvey, 2007). These leadership roles consist of the necessary and unavoidable interaction between bureaucratic and administrative functions but also emergent and informal complex adaptive system dynamics. The Complex Adaptive Systems (CAS) are the social networks embedded in an organisation or society consisting of interconnections, dynamic ties, shared goals and needs (Uhl-Bien, Marion & McKelvey, 2007).

Although the complexity leadership theory emerged from various sources, it has significantly benefited from systems thinking, complex adaptive systems theory and theoretical biology among others (Brown (2011). Complex systems need a different kind of leader to manage complexity. Complexity leadership is characteristically a collaborative resultant product of three different types of leadership (Uhl-Bien, Marion & McKelvey, 2007):

- Administrative leadership

- Adaptive leadership

- Action-centred leadership

This study considers the Nima Community as a Complex Adaptive System given the fact that the locality has several embedded interconnections and its constituents have shared goals and needs. Suffice to say, leaders in the community must recognise the complex milieu within which they operate in order to deploy the necessary administrative, adaptive and action centred leadership skills that can bring about desired change in the community. The study focuses on complexity leadership within the context of solving problems within multi-ethnic and religious inner-city community.

Social Exchange Theory

The Social Exchange Theory (SET) was propounded in 1958 by George C. Homans an American sociologist. The earliest postulation of the theory appeared in a publication by Homans titled “Social Behaviour as Exchange’’. However, the subsequent development of social exchange theory has benefited from the contribution of other scholars, notably Peter M. Blau and Richard M. Emerson (Molm, 2000).

At its core, social exchange theory explains social change and stability as a procedure of negotiated exchanges between individuals or parties. The theory dwells on the sociological and social psychological perspectives to rationalise social transaction. One of the fundamental propositions of the social action theory is that human beings create relationships through the use of a subjective cost-benefit analysis of situations and by comparing alternative courses of action (Moore, 2004).

SET is one the most significant theoretical paradigms for exploring the development and dimensions of begging in society (Perrone, Zaheer & McEvily, 2003). In a multidisciplinary review of the evolution of social exchange theory, Cropanzano and Mitchell (2005) contend that the social exchange theory has been used to explain social action in different circumstances namely; networks or relationship building, social power, organizational justice, work place interdependence and psychological contracts among others.

The social exchange theory is about interdependence of transactions in society. The main tenets of SET are that social action is guided first by rules and norms of exchange, secondly social exchange implies resource exchanged, and thirdly relations relationships emerge from social exchange.

Methodology

A qualitative research approach was adopted for this study and the single case study design was used. This design was suitable because it enabled the researcher to gather different forms of data from respondents in their natural setting. As characteristic of case studies researcher employed a combination of techniques to obtain data (Yin, 2009) from selected beggars and community leaders in Nima, a suburb of Accra, Ghana.

Nima is a low-class residential settlement populated by immigrants from different parts of Ghana and other parts of Africa. The community has become an inner city following the inability of city authorities to implement sufficient urban planning mechanisms.

To obtain insights into the issues of interest, the researcher strategically selected individuals, groups, and settings in order to maximize understanding of the nature of begging and how the menace can be addressed through grassroots action. The study predominantly relied on primary data which was obtained from beggars, NGO workers, traditional rulers and religious leaders in the Nima community.

In all, a sample size of fifty-six (56) respondents participated in the study. This consisted of fifty (50) beggars (27 males, 23 females) and six (6) community leaders. The leaders selected included two religious leaders, two traditional leaders and two NGO workers in the community.

Convenient sampling strategy was used to sample beggars whilst purposive sampling was used to select community leaders. Semi structured questionnaire and in-depth interviews were employed for data collection in this study. Creswell (2006) supports the use of different data collection strategies in case study designs and asserts that the main idea behind data collection in qualitative studies is to gather information from different sources using the same or parallel constructs or concepts.

Semi-structured questionnaires were used to obtain data from sampled beggars whilst interview guide was used for in-depth face-to-face interviews with community leaders selected for the study. Data obtained through questionnaire was analysed using the descriptive analysis technique via Statistical Package for Social Scientists (SPSS), interview responses were also subjected to thematic analysis.

Findings and analysis

Demographic characteristics of the beggars

All the beggars who participated in the study were matured. Majority (38%) of them were 40-49 years, 15 (30%) were 30-39 years and 11 (22%) were 50-59 years. In addition, 2 (4%) of the beggars were 18-29 years and the remaining 3 (6%) were above 60 years. Cumulatively, more than a quarter of the beggars were fifty years and over. In addition, the beggars hailed from different countries (Niger, Mali. Burkina Faso, Sudan), but majority (54%) were Ghanaians.

Nature of begging in the Nima Community

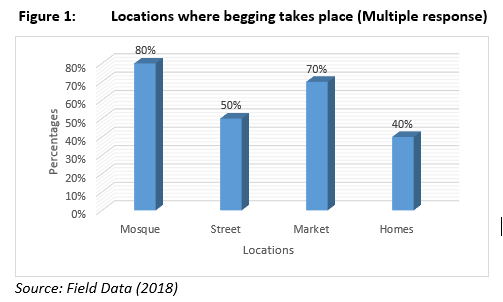

The first of objective focused on the practices of beggars in the Nima Community. It was revealed that most (64%) of the have been beggars for over five years. For these people, begging is a way of life. Begging in Nima takes place at any public place that beggars find appropriate. Majority of them beg at more than one location as can be observed from Figure 1.

Figure 1: Locations where begging takes place (Multiple response)

As shown in the Figure 1, beggars at Nima beg at different locations. Majority of them beg at more than one location. However, most of them 80% beg around the mosques, 70% beg around the market. A similar number of respondents (50%) also indicated that they beg on the street and in homes. However, most of them beg around the mosques especially on Fridays. Begging is also prevalent around the market and on the street. Some beggars also visit people’s homes to ask for alms. Selected community leaders also shared their thoughts on the nature of begging at Nima. In fulfilment of the anonymity promise made to respondents, the names and exact designations of interview respondents are replaced with an apha-numeric coding system. In that, the first interview respondent is presented as IR-1 (Interview respondent-one), the second is also presented as IR-2 (Interview respondent two) and so on.

In an interview with an Imam (Islamic religious leader) he indicated that some of the beggars are children or young people who appear to be learning the trade of begging in the company of an adult. The respondent explained that this is a common phenomenon especially on the streets close to the market.

Me its children I often see. They don’t look Ghanaian, they are usually with an older person who sort of tells them what to do and they give their earnings to the grown up in their company. So it is as if the children are being mentored or they are learning [to] become beggars (IR-3).

The perspective of the traditional leader shows a situation where young people are led by adults into begging. The respondent also reveals that some of the beggars might be foreigners. This perspective is in line with the demographic characteristics of respondents as it was earlier reported that some of the beggars are from other parts of Africa such as Mali and Burkina Faso.

It was further revealed that some of the beggars have particular locations or spots that they occupy every time while others move about. Respondents explained that several beggars seem to have laid claim to particular spots like the entrance of the Nima market or some busy bus stops. Such beggars report in the morning and remain at the spot or the area until evening when they retire or until such a time that the place is no longer busy

Community leaders explained that Fridays are usually the busiest days for roaming beggars as they try to position themselves in front of the mosque or in close proximity to the mosque so that they would be easily noticed and given alms.

As for Friday you will see many of them around the Mosque. Some of them we don’t even know them in the community but they come to us for alms. They travel from place to place for alms (IR-1).

The beggars were also found to be using various active and passive techniques. One community leader (religious leader) explained:

One religious leader said:

Some of them you can’t really understand them [beggars], they appear very misleading. The last time I personally met a man, he appeared untidy with plenty beard. When he is approaching you he offers continuous prayers from the moment he sees you until you walk away or give him something (IR-4).

The response describes a religious beggar. Such beggars usually hang around mosques and approach people who visit the mosque for prayers. There are also beggars who visit offices and people’s work places in search of alms.

One NGO worker explained;

Here in my office we handle cases such as marriages, divorces, family management issues among several others but frankly speaking my office has become the centre of begging. Every day we are inundated with the number of beggars who visit our office. In fact, it is unbelievable (IR-2)

The response of the NGO worker demonstrates the pervasiveness of begging in Nima. It appears the beggars do not have limitations or boundary, they can go anywhere in the community in search of alms.

Perspectives of Community leaders about begging

The second objective of the study focused on examining the views of religious, traditional and opinion leaders about beggary in the Nima community. The perspective of leaders about begging in the community is a good indicator or how leaders understand and define the menace, it is also a good precursor of how they identify with the problem. This objective was addressed through interview responses only, and the themes that emerged are explained below.

‘They are not from here’

Respondents indicated that many of the beggars do not hail from the Nima community or even Ghana. As One NGO worker remarked;

Some groups of beggars are refuges from countries such as Niger, Nigeria, Chad, and Sudan. Currently we have lots of them and they are given special attention. Some of them have been adopted (IR-6).

Begging is disgusting

Community leaders expressed their disgust about begging. They considered begging to be a lowly activity associated with much embarrassment especially when it is not justifiable. Community leaders were particularly appalled by the involvement of abled bodied men and women in begging. They considered this to be a serious problem that has not been given the attention it deserves.

In describing the activities of beggars in Nima one Zongo Chief lamented;

It’s so disgusting especially the involvement of abled body men and women because our communities are so humanitarian and very benevolent. The use of the name of God to beg send shivers into the spines of Muslims. The situation is pathetic and demands immediate attention (IR-4).

The direct quotations provided here indicates that respondents are appalled by the incidence of begging and the situation seems helpless.

Begging has adverse consequences

Community leaders explained in various interviews that begging has many dangerous effects on those involved in begging and on the community or society at large. Community leaders consider the loss of productive capacity as a major consequence of begging. One opinion leader who also heads an Islamic charity stated that;

Begging promotes laziness and retards personal development. When people are lazy and unskilful they cannot contribute to national development. It breeds social vices. It circulates a formula of poverty in some families since there is no one working hard to establish the rest of the household (IR-5).

Another leader described the consequences of begging from a religious perspective;

People who beg undeservedly openly invite poverty into their home and will be tormented in the next world. There is no honour and dignity in begging (IR-1).

This response shows that whereas the immediate consequence is loss of productivity, begging may lead to social vices and poverty in the long term. This is true because begging is not a sustainable economic activity. As such, able bodied individuals who resign to begging deprive themselves of the opportunity to seek out ventures that require the creative use of their capabilities to irk a living.

The role of leadership in addressing the prevalence of begging in Nima

In finding out the role of leadership in addressing the prevalence of begging in Nima, beggars were first required to indicate the measures that leaders can consider in addressing the menace of begging. The questionnaire results are presented in Figure 2.

As can be observed from Figure 2, all the beggars (n=50) believed that family support and religious support are the best means for addressing begging. Many of them (82%) selected social welfare, 80% opted for social inclusion but only 2% selected law enforcement. The responses are indicative that the there is no one mechanism for addressing begging but rather a combination of strategies.

During the interviews, community leaders also identified various measures which they believe can be put in place to address begging. The measures suggested by community leaders are as follows; provision of alternative livelihood, condemnation of unjustified begging, change of mind-set and enforcement of Anti-Begging Laws.

Provision of alternative livelihood

Community leaders were frank in their admission that it is incumbent on them leaders to mobilise support and funding to provide alternative sources of livelihood for beggars. The traditional and religious leaders especially believed that although not every beggar is a Muslim, the establishment of rehabilitation centres can be a Muslim initiative but for the entire Nima community.

One Imam (Religious leader) stated;

Muslims are fragmented and work as individuals and this won’t take us anywhere. We need to make collective efforts to fight this menace. …… We must establish vocational and rehabilitation centres for beggars to provide equip beggars with trade and other skills to make them economically independent. Child beggars must be motivated to go back to school (IR-3).

An opinion leader in the community also echoed similar sentiments in different words;

We must initiate something as a community to rehabilitate and empower our people to be financially and economically independent (IR-5).

Condemnation of unjustified begging

Community leaders were also of the view that not all beggars should be tolerated in the community as some beggars are only taking advantage of people. The leaders continuously pointed to Imams especially as people having the influence and platform to champion the campaign to openly condemn unjustified begging.

I call on Muslim leadership to campaign against begging most especially in the mosque to save their future generation. This initiative must be pursued vigorously and strategically short term and long term (Verbatim response of IR-1).

This call made by an alarmed respondent is manifestation that Muslim leaders have an opportunity to address the problem of mosque begging using the mosques as platforms of advocacy.

Change in mind-set

It was revealed that community leaders can also use their influence to convince or talk beggars out of the act by exposing them to new realities or by letting them know their situation is not as hopeless as they think.

One respondent indicated that;

There’s is the need for vigorous campaign against begging to conscientise and re-orientate beggars to change their conditions or circumstances by taking advantages of the opportunities available. There is no dignity in begging (IR-3).

Enforcement of Anti-Begging Laws

Respondents also mentioned that the state, especially law enforcement bodies have a role to play. Community leaders indicated that the state has a role to play by ensuring that laws on begging are obeyed. It was clear from the responses that although the role of community leaders is critical, they have to work closely with state agencies if the menace of begging is to be addressed in Nima.

Discussion of results

The nature of begging as found out in this study is consistent with the position of Kothari (2012) that begging is simply asking for something and beggars employ different techniques including persuasion and plea. In the case of beggars at Nima, most of them beg for money or cash rather than food or other materials. The findings are also in tandem with Clark (2007) which reported earlier that beggars are usually people who are disadvantaged in society but they take advantage of their disadvantage by not engaging in productive work.

Also, as found out by this study, beggars are diverse as suggested by Dimoso (2012). Beggars cut across age range, ethnicity and nationality. In spite of this study’s focus on matured beggars, it was revealed that child begging is also common in Nima, this demonstrates the seriousness of begging as a political and economic consequence of societal structure and actions as mooted by Weiss, (2007).

The diversity of beggars and the dynamic nature of begging is also in line with Namwata, Mgabo and Dimoso (2012) who explained some beggars have been begging all their lives and are likely to continue doing so because they have been born into families of beggars. However, unlike previous studies, this study revealed that beggars in the Nima community do not have boundaries and they can visit homes and even offices for alms.

The nature of begging in Nima also demonstrates the transactional nature of begging which is in line with the Social Exchange Theory. In the case of religious beggars especially, beggars exchange their prayers for alms. At its core, social exchange theory explains social life as full of negotiated exchanges between individuals or parties. From the social exchange theory perspective, beggars and their benefactors cooperate with each other making begging a form of interdependence and a transaction.

Regarding the perspectives of leaders about begging, it was realised that although the opinion leaders, religious leaders and traditional rulers are aware that begging is a problem in their community, not much has been done because these social actors are part of the system that views begging as a quid-pro-quo Thus the beggars are given alms, and the givers receive blessings. This further establishes the transactional nature of begging as explained from the SET perspective.

The findings also show that although community leaders variously identified begging as a major social menace, they have not taken much decisive action to address the menace. Religious leaders, opinion leaders and traditional rulers are not living up to the expectations of the complexity leadership theory as they failed to demonstrate adaptability and action orientation demanded to arrest the menace of begging. The leaders have not sufficiently demonstrated the roles of leaders in complex adaptive systems as suggested by Uhl-Bien et al. (2007).

Further, in terms of what community leaders can do the finding of the study support the surmise of Weiss (2007) that there should be opportunities for religiously oriented mobilisation that combines individual salvation and commitment to community welfare which are both important principles in Islam.

Thus, Muslim leaders must encourage faithful to rethink the practice of giving and receiving in a manner that is sustainable and does not encourage able bodied men to pose as beggars. However, from the under the complexity leadership theory thinking, the efforts of the leaders must be collaborative. It suffixes that traditional, religious and opinion leaders must work together in order to address the menace.

This is important because all leaders wield some influence and authority but the impact of their efforts will be greater if they work together. In addition, stricter enforcement of anti-begging laws could serve as a deterrent to beggars, but this is an unpopular solution as Johnsen and Fitzpatrick (2008) earlier revealed. It goes without saying that as Weiss, (2007) observed, the problem of begging is deep rooted and cannot be pushed aside with laws, more money or mere talk, measures to address begging must be holistic and inclusive.

Conclusion

First, the conceptualisation of the begging in Ghanaian communities such as Nima requires further rethinking and proper definition as this is often linked to religion in the wrong way. Muslims were noticed to be familiar with several charitable practices such as Zakat, Sadaqa and Waaf but Islam does not encourage begging per say. Notwithstanding, the tolerance for some forms of begging makes it difficult to stand against begging in Muslim communities. Again, Islamic leaders, traditional rulers and local authorities have not collaborated enough to bring begging under control, giving ‘fake’ beggars the chance to take advantage of the situation

Also, consistent with the position of the complexity leadership theory perspective, community leaders are willing to take up the responsibility to work with the police, the state, the mosque and the Nima community in addressing the menace of begging. In effect, the leaders are opening up for more interaction, which is exactly how problems are solved in complex adaptive systems. Meanwhile it is important to note that no single strategy can arrest all forms of begging. As such, it is important for community leaders in Nima to collaborate in deploying holistic measures to address the problem. Every major institution and every leader in the community has a role to play.

The study recommends that the identified measures for addressing begging ought to be considered as tactics that are deployed within an overarching strategy that seeks to address the incidence of begging in the Nima community. More importantly, addressing begging must be inclusive and participatory; giving beggars the opportunity to partake in their redemption.

>>>Imam Abdul-Karim Abass Umar, the principal author, is the Deputy Imam (Civilian) at the Ghana Police Mosque, Cantonments – Accra. Mobile: 0266314422

>>>Dr. Adam Salifu, the Supervisor/Co-Author, is a Research Fellow, Research and Consultancy Centre| Lecturer, Business Administration Department | University of Professional Studies, Accra. Postal Address: P.O. Box LG 149, Legon-Accra; Mobile: +233 (0) 277868758

References

- Amanchukwu, N. R., Stanley, J. G. & Ololube N. P. (2015). A review of leadership theories, principles and styles and their relevance to educational management. Management 5 (1), 6-14

- Baltacı, A. & Balcı, A. (2017). Complexity Leadership: A Theoretical Perspective. International Journal of Educational Leadership and Management, 5(1), 30-58.

- Benattia, T., Armitano, F. & Robinson, H. (2015). Irregular migration between West Africa, North Africa and the Mediterranean. Abuja: FMM West Africa/IOM Nigeria

- Clark, C. H. (2007). Compass of society. New York: Lexington Books.

- Creswell, J. W. (2006). Educational Research: Planning, Conducting and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research (2nd ed.). New Jersey: Pearson Educational Inc.

- Emmett, C. F. (2001). Jerusalem as a Holy city for Muslims. BYU Studies, 40 (4), 119-135.

- Groce, N., Loeb, M., & Murray, B. (2014). The disabled beggar literature review: begging as an overlooked issue of disability and povertyGeneva: International Labour Organization.

- Johnsen, S., & Fitzpatrick, S. (2008). The use of enforcement to combat begging and street drinking in England: A high risk strategy? European Journal of Homelessness, 2 (1), 191-205.

- Kaushik, L. (2014). Rights of Children: A case study of child beggars at public places in India. Journal of Social Welfare and Human Rights, 2 (1), 1-6.

- Kothari, J. (2011). Maanas individual and society (5th edition). Kajasthan: Patrika Publication.

- Martiskainen, M. (2017). The role of community leadership in the development of grassroots innovations. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 22 (1), 78-89.

- Molm, L. D. (2000). Theories of social exchange and exchange networks. In G. Ritzer, & B. (Smart, Handbook ofsocial theory (pp. 260-272. ). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

- Namwata , M. L., & Mgabo, M. R. (2012). Feelings of beggars on begging life and their survival livelihoods in urban areas of central Tanzania. International Journal of physical and social sciences, M. L. Mgabo, M R.

- Ogunkan, D. V. (2011). Begging and almsgiving in Nigeria: The Islamic perspective. International Journal of Anthropology , 3 (4) 127-131

- Osa-Edoh, G., & Ayano, S. (2012). The prevalence of street begging in Nigeria and the counseling interventions strategies. Review of European studies, 4 (4) 77-84.

- Owusu-Sekyere, E., Jengre, E., & Alhassan, E. (2018). Begging in the City: Complexities, Degree of Organization, and Embedded Risks. Child Development Research, 1-9

- Perrone, V. Z., & McEvily, B. (2003). Free to be trusted? Organizational constraints on trust in boundary spanners. . Organization Science, 14 (1) 422-439.

- Sewanu, O. A. (2014). Dealing with the menace of steet begging. Retrieved from Nigerian observer: http://nigerianobservernews.com/03092014/03092014/features/features7.html#.V74a-jXRUqI

- Smith-Asante , E., & Awiah , D. M. (2015). Begging for a living: The life of Accra’s street beggars. Retrieved 08 24, 2016, from Graphiconline: http://www.graphic.com.gh/features/features/begging-for-a-living-the-life-of-accra-s-street-beggars.html

- Tambawal, M. (2012). Effects of street begging on national development: counselling implications. Sokoto: Unpublished disertation submitted to Osmanu Danfodiyo University.

- Tieleman, J., & Uitermark, J. (2018). Chiefs in the City: Traditional Authority in the Modern State. Sociology, 11 (1), 1-17

- Tourish, D. (2018). Is complexity leadership theory complex enough? A critical appraisal, some modifications and suggestions for further research. Organisation Studies. 40 (2), 219-238

- Uhl-Bien, M., Marion, R., & McKelvey (2007). Complexity leadership theory: Shifting leadership from industrial age to knowledge era. West Harford: The Clarion group

- Weiss, H. (2007). Begging and almsgiving in Ghana, Muslim positions towards poverty and distress. Stockholm: Elanders Gotab AB.

- Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods (4th Ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.