Mali could become a ‘failed state’, unless ECOWAS leaders take strategic and pragmatic decisions to end the incessant military and jihadist interventions in the troubled Sahelian country’s management.

Almost five years since a Tuareg rebellion and coup d’état, Mali has been struggling to return to a normal state. The recent military coup is sending strong signals that the once-prosperous ancient empire and successful modern state since independence in 1960 is in danger of sliding into failed-state status – unless the international community acts fast.

The reason Mali should be the concern of ECOWAS is those jihadist activities and incessant military interventions have created the breeding ground for armed extremists and terrorist groups to thrive. Like a cancer, this could spread to the rest of West Africa. Evidence shows that Burkina Faso is directly impacted by the instability in Mali, with jihadists using Mali as a breeding ground and a launch-pad for attacks on Burkina Faso. Over time, Mali has become the development and democratic challenge for West Africa – given that out of the 15 ECOWAS states, only Mali currently has military rulers.

Security challenge

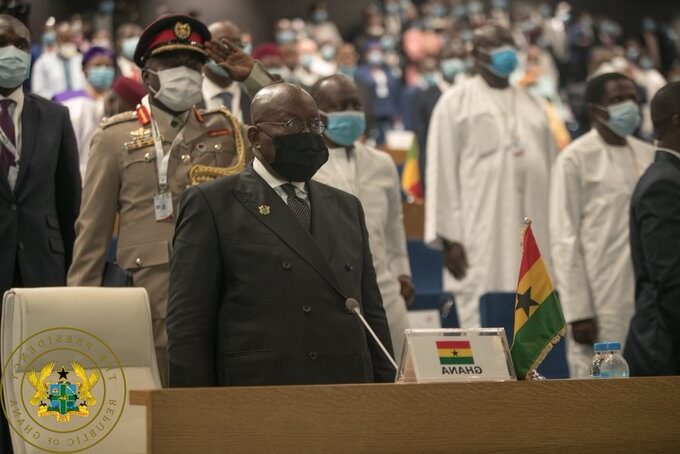

This is a security challenge confronting President Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo as the new Chair of ECOWAS. During the 57th Summit of the Authorities of ECOWAS Heads of States and Governments in early September, Ghana was unanimously elected as Chair of the ECOWAS authority for one year. The election of President Akufo-Addo three months into Ghana’s presidential elections has evoked various interpretations.

One view is that the vote of confidence the ECOWAS leaders gave President Akufo-Addo is as good as encouraging Ghanaians to retain him as president.

This is because I have not seen any ECOWAS regulation which suggests that if the current holder loses an election, his/her successor could automatically assume the role of Chairman on behalf of the country. In other words, the Chairmanship might not be transferable. Undoubtedly, President Akufo-Addo’s strategic leadership in managing the COVID-19 pandemic, coupled with his global recognition as a visionary leader, was the underlying reason for the vote of confidence in him.

The Head of Authority is the supreme institution of the community, and is responsible for the general direction and control of the ECOWAS community. The authority takes action on all matters of conflict prevention, management and resolution, peace-keeping and security, as covered by relevant protocols. A few days after assuming the role of Chairman, President Akufo-Addo convened a consultative meeting in Accra on Tuesday 15th September 2020 to deliberate on the leadership crisis in Mali. The meeting was called after initial mediation efforts by the presidents of Ghana, Ivory Coast, Niger, Nigeria and Senegal in Mali’s capital, Bamako, failed to end the impasse.

Immediate cause

The military intervention was prompted when thousands of Malians, led by the opposition ‘June 5 Movement’ took to the streets and demanded the resignation of ousted Malian President, Ibrahim Boubacar Keita – citing pervasive corruption, extreme poverty, and protracted conflict. According to media reports, dissatisfaction over the country’s economic woes, corruption and worsening security had been simmering for a while. The media reported that the immediate cause of the current crisis was a decision by the Constitutional Court in April 2020 to overturn the results of parliamentary polls for 31 seats, which would have ensured that candidates with Keita’s party were re-elected.

The protests turned violent earlier in September when three days of clashes between security forces and protesters killed 11 people. Several opposition leaders were also briefly detained. My worry is whether a court decision is enough justification for civilian unrest and military intervention. What has happened to the rule of law in Mali? Perhaps Malians should take a cue from the 2012 landmark election petition in Ghana.

Despite the petitioners’ dissatisfaction with the final verdict, they signalled Ghanaians to put the case behind them and let the country move on. Opposition parties in Mali should be oriented to accepted that their role is to provide alternative policies to the government – not creating a festering environment for the military to intervene. As long as the military continue to meddle in power, democracy will be the loser in Mali and West Africa.

Until the current spate of unrests, Mali had earned an enviable record as a thriving democracy since 1992, when Alpha Oumar Konaré won Mali’s first democratic, multi-party presidential election before being re-elected for a second term in 1997. Sadly, since 1997 the once-politically stable country has faced leadership crises – with the military and jihadists taking a turn to reverse the country’s gains. Like the prior ones, the current unrest risks further destabilising a region already battling an alarming increase in violent extremism and poverty.

Poverty

The UN Secretary-General, Mr. António Guterres, recently told the Security Council that the only way to prevent increased violence and instability in Mali is to tackle the root causes of poverty: underdevelopment, climate change, competition for resources, and the fundamental lack of opportunities among the youth of Mali.

Mr. António Guterres indicated that 3.7 million people, including 1.6 million children, are confronted with a major humanitarian crisis. This grave situation is exacerbated by intense inter-ethnic conflicts between the Fulani and Dogon ethnic groups, which are the underlying cause of instability and underdevelopment in Mali.

Ranked 175th out of 188 countries on the United Nations Development Programme’s 2016 Human Development Index, Mali is one of the poorest countries in the world; with nearly 45% of its population living below the national poverty line. Also, almost 65% of the Malian population is under 25 years of age and 76% live in rural areas. Mali, a vast Sahelian country, has a low-income economy that is undiversified and vulnerable to commodity price fluctuations. Poverty is concentrated in the rural areas of southern Mali (90%), where the population density is the highest. Moreover, Mali’s population at an annual growth rate of 3.0% is among the fastest-growing among developing countries.

Equally worrying is that life expectancy at birth in Mail is just 58.5 years; one of the lowest of any country in the world. Mali is also facing serious environmental challenges such as desertification, soil erosion, deforestation, and loss of pasture. Mali also has a shortening water supply amid climate-change and threats of desertification. For decades, Mali has been hit by droughts, a condition that is threatening food security and loss of livelihoods. Small wonder then, that with little opportunities for survival, violent crimes – such as kidnapping, abduction, killing and armed-robbery – are common among the youth of Mali.

Legacy of Mansa Musa

During the peak of the kingdom, Mali was extremely wealthy due to the tax on trade-in and out of the empire, along with all the gold Mansa Musa accrued. History indicates that Mansa Musa had so much gold that during several pilgrimages to Mecca, he gave out gold to all the poor along the way; a gesture that triggered inflation throughout the kingdom.

In fact, Mansa Musa still holds the record as the richest man that ever lived in Africa. Arguably he had four times the US$10.5billion Aliko Dangote currently holds as Africa’s richest man. But the question remains: “What happened to all the wealth Mansa Musa accumulated?” Why is Mali among the poorest countries in the world, despite all the wealth of Mansa Musa and the mineral resources?

History indicates that Mansa Musa used his wealth mostly in pursuit of territorial expansion and personal aggrandisement; such as several pilgrimages to Mecca and marrying many women. At independence in 1960, Ghana had to support Mali with a grant as part of Kwame Nkrumah’s policy of promoting economic and political integration. This is a sad commentary and reflection of how some African leaders used and continue to use the continent’s resources.

Return civilian rule

West African citizens, and by extension, all Africans, must be getting tired with the continuing unrest in Mali. For this reason, I join many Africans to demand that the military stay out of politics in Mali. Our leaders should send a strong message to the military in Mali to concentrate on their core duty of protecting the territory of Mali from jihadist invasions. Mali’s recent unrest began with a 2012 coup, hatched by soldiers opposed to what they saw as a weak response to a growing separatist insurgency by Tuareg rebels in the country’s north.

The insurgents were armed with weapons from nearby Libya, following that country’s 2011 civil war. Western powers should be partly blamed for creating the instability in Libya by ousting Muammar Gaddafi and putting Mali on the receiving end. That said, my simple understanding is that the military’s core job-responsibility is to protect the territorial integrity of their country. So, if jihadists invade the country, the military should stay and fight them; rather than interrupting the governance process.

Meddling in politics

In fact, some security analysts have argued that the recent coup was unnecessary, given that the elected government had 18 months to end its tenure. This suggests that the military in Mali has simply developed a taste for meddling in politics. Thus, they should be reoriented to accept that in this era, Africa can no longer tolerate military meddling in civilian politics.

At the Accra meeting, the military junta tabled two requests as conditions for returning Mali to civilian rule. Firstly, they asked for a three-year transition period. Secondly, they requested that the military be allowed to lead the transition. Thankfully, the leaders rejected their requests in a move that sent strong signals EOCWAS will no longer countenance the military continually meddling in civilian politics. Instead of three year-transition, the Mali military was given 18 months to return the country to democratic rule. ECOWAS leaders also turned down the military’s request to lead the transition, insisting that the transitional government should be headed by civilians.

More sanctions

ECOWAS leaders threatened further sanctions if the military leaders fail to adhere to the conditions for a return to civilian rule reached at the 15th September meeting. President Akufo-Addo told the media after the meeting that Col. Assimi Goita had agreed to engage his National Committee for the Salvation of the People (CNSP) leadership to agree on measures to implement its commitments agreed at the ECOWAS meeting.

ECOWAS leaders should be resolute in their pursuit of a lasting solution to the situation in Mali. The regional security concerns could manifest physically if the crisis lingers on. Not only will Mali descend into chaos, but instability could affect morale of the military and weaken its fight against the terrorist groups. In that case, there is a risk that neighbouring countries like Burkina Faso, Senegal and Guinea will be affected.

If it is true that Ivory Coast’s President Alassane Ouattara is bent on changing the constitution to run for a third term, he presents another challenge to EOCWAS leaders. President Akufo-Addo has the arduous task of talking to his friend to respect the constitutional arrangement of Ivory Coast. Ivory Coast remains volatile, despite some period of stability after the crisis of 2000-2010. For this reason, Ouattara’s personal ambitions should not be allowed to return Ivory Coast to the dark days.

(***The writer is a Development and Communications Management Specialist, and a Social Justice Advocate. All views expressed in this article are my personal views and do not represent those of any organisation(s). (Email: [email protected]. Mobile: 0202642504/0243327586