By Felix Larry ESSILFIE (Dr)

Ghana’s gold sector has delivered a historic export windfall in late 2024 and early 2025. In 2024 gold shipments reached about USUSD$11.6 billion (a ~53% jump from 2023), accounting for roughly 57% of total exports.

Small-scale mining played a major role: output was estimated at 151 tonnes in 2024 (versus ~120t in 2023), with artisanal miners contributing over 40% of output.

Buoyant production plus record prices (gold broke USD$3,300/oz in April 2025) have propelled export earnings higher.

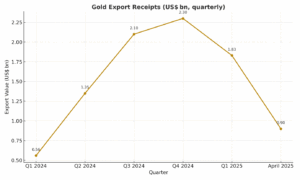

For example, 2024 earnings surged to roughly USD$4.5bn, with Q1 2025 around USD$1.83bn and April 2025 alone about USD$0.9bn making a total of USD$2.73bn in the first four (4) months of 2025 (see Figure 1 below). This export boom has sharply improved Ghana’s external balance.

Figure 1: Ghana’s gold export receipts (USUSD$ bn, quarterly). Data: Bank of Ghana; Gold Board. Increased volumes and high prices drove 2024–25 revenues to record levels.

These inflows have translated into an unprecedented reserve build-up and current account surplus. Gross international reserves climbed from about USD$6.0bn in early 2024 to nearly USD$10.7bn by April 2025.

Import cover rose from ~2.7 months to ~4.7 months of imports over the same period (see Figure 2 below). In effect, Ghana’s current account swung into healthy surplus territory (around +2–3% of GDP annualized) due to gold export gains. Capital and financial flows – including strong remittances – have further bolstered reserves.

Figure 2: Ghana’s gross reserves (left axis) and import coverage (right axis) have jumped since mid-2024, reflecting the gold-led current account turnaround. Data: Bank of Ghana.

The gold bonanza has also influenced the exchange rate and inflation. The Cedi strengthened significantly in early 2025: the USD/GHS interbank rate fell from about 15.5 in late 2024 to roughly 12.0 by May 2025, aided by ample dollar supply and central bank intervention.

The real effective exchange rate (REER) saw a large swing as the Cedi first over-appreciated in mid-2024 (REER index up ~15% from Apr to Oct 2024) and then eased back as policy adjusted (index down into early 2025). The Figure 3 below contrasts the nominal and real moves.

On balance, the post-surge exchange-rate rally has compressed import prices and, together with tight monetary policy, helped curb inflation. Consumer prices peaked near 25% year-on-year in late 2024 but fell to about 21.2% by April 2025. That said, inflation remains well above the Bank’s 8±2% target band, reflecting residual second-round effects and supply constraints.

Figure 3: Ghana’s FX rate (USD per GHS, left axis) and real effective exchange rate (right axis, index) around the gold surge. The Cedi appreciated in early 2025 after over-depreciating in 2024. Data: Bank of Ghana.

On the fiscal side, higher gold revenues (royalties, taxes, dividends from mining companies) have strengthened government receipts, though exact figures remain provisional.

It is estimated that fiscal revenue from gold mining climbed from roughly USD$1.5–2.0bn in 2022–23 to about USD$2.3bn in 2024, with projections near USD$3.0bn in 2025 if current trends continue (Figure 4 below). This includes mining royalties (5% of output value) and corporate taxes. The windfall has enlarged non-oil revenues in an otherwise constrained budget.

However, preliminary budget execution through 2024 shows sizable fiscal slippages: unbudgeted payables accumulated and the primary balance swung to a deficit (~‒3.3% of GDP by end-2024) instead of the targeted surplus. The new government’s 2025 budget aims to recoup discipline (targeting a 1.5% of GDP primary surplus) via tightened expenditure rules.

Nonetheless, the gold boom has marginally improved fiscal space: stronger revenue inflows soften near-term financing needs (see hypothetical trend in Figure 4 below). Still, reliance on volatile commodity revenue heightens fiscal risks.

Figure 4: Hypothetical Ghanaian government receipts from gold (mining royalties and taxes) and forecasts. Stronger export prices/volumes drove a steep revenue rise in 2024–25. (Data: MOF/BOG estimates.)

Debt dynamics have also benefited from the windfall-driven growth. With real GDP surging above program expectations (IMF staff noted higher growth underpinned by mining), the debt-to-GDP ratio is on a declining path. Using the revised (2021-base) GDP series, Ghana’s public debt fell from ~69% of GDP in early 2024 to roughly 55% by early 2025.

Nevertheless, sustainability depends on continued discipline and restructuring. In particular, Ghana’s external debt stock is still high (over USD$28bn). The ongoing debt restructuring under the G20 framework is vital.

In the meantime, excess gold income offers an opportunity to bolster reserves (and stabilization funds) or prepay expensive debt. The Ministry of Finance has indicated that part of the mineral proceeds could be set aside into a buffer fund (akin to the oil Heritage Fund) to smooth volatility.

The broader context is that several African peers enjoyed similar gold-driven surpluses, though Ghana stands out for sheer magnitude. As of 2023, Ghana led Africa in gold output (~135 tonnes), ahead of South Africa ((~104t), Mali (~95t) and Burkina Faso (~93t). The Figure 5 below compares the 2023 production of these top producers.

In nominal export terms, South Africa’s gold exports (about USD$26bn in 2023) exceed Ghana’s, but Ghana’s smaller economy means gold has a far larger relative impact. Global trends also reinforce Ghana’s fortunes: gold prices have climbed 67% since early 2024, reflecting easing real interest rates and safe-haven demand. Thus, unless prices reverse, Ghana’s windfall is likely to persist through 2025–26.

Figure 5: Selected African gold producers – Ghana, South Africa, Mali, Burkina Faso – and their 2023 output (tonnes). Ghana leads the continent in production, underpinning its export gains.

From a balance-of-payments perspective, Ghana’s current account and reserves rose via the export-led surplus.

In a simple goods-market model, the gold windfall shifts the external savings curve upward and raises aggregate demand. Under a fixed money supply, the additional foreign currency inflow increases reserves, shifting the LM curve right and tending to lower interest rates (though Ghana has maintained tight rates). In IS–LM terms, the gold shock is expansionary: higher gold export raises national income, partly offsetting fiscal contraction.

The Mundell-Fleming model with a floating rate suggests some exchange-rate appreciation (as seen) and a reduction in net exports of other goods – the classic Dutch Disease channel.

Indeed, the real Cedi strength could hurt other exporters or import-competing industries. Policymakers must monitor whether non-resource sectors are squeezed by the currency effect and adjust accordingly (e.g. via gradual exchange-rate policy or targeted support).

The government has emphasized building buffers and prudent rules. Ghana’s existing Heritage & Stabilization Fund (HSF) for oil could analogously receive a share of gold windfalls.

Committing a fixed fraction of gold revenues to reserves or a sovereign fund would help damp volatility and provide countercyclical support. Strengthening fiscal rules (as under the new Fiscal Responsibility Act and improved PFM frameworks) can lock in savings rather than one-off spending.

On the monetary side, the Bank of Ghana has signaled tolerance for some nominal appreciation (through FX sales) to avoid inflationary pressures. However, it must also guard against overshooting; a sharp jump in the Cedi could destabilize exporters and debt-service costs on domestic-currency debt.

A structural opportunity is domestic value addition in the gold sector. Ghana currently exports mostly raw and semi-processed gold. Developing local refining, jewelry, or electronics uses could retain more income.

Creating incentives for artisanal miners to sell through formal channels (the new Ghana Gold Board Act of 2025 mandates a regulated market) should reduce smuggling and increase tax capture.

In parallel, revenue from gold should be invested in diversification – bolstering agriculture, infrastructure and industry – to avoid over-dependence on mining. Good governance in the mining sector (transparent contracts, enforcement of mining codes) will maximize the public benefit of the boom.

Ghana’s gold export windfall in 2024–25 has profoundly altered the country’s macroeconomic landscape. The surge has shored up external balances, eased foreign currency constraints, and provided fiscal space. But it also poses challenges: managing inflation, exchange-rate swings, and “Dutch Disease” risks.

The recommended policy response combines prudent saving (stabilization funds and debt repayment), rigorous fiscal discipline, and strategic investment in the non-mining economy. When guided by sound macro-fiscal frameworks (per IMF program targets) and structural reforms, Ghana can use this gold boom not just for a short-lived uptick, but as a catalyst for stable, diversified growth.

The writer is the Executive Director, IDER