“There must be a better way to make things we want, a way that doesn`t spoil the sky, or the rain or the land”

———–-Paul McCartney

In recent years, the global financial landscape has undergone a notable transformation as investors increasingly seek to align their capital with environmental, social, and governance (ESG) values.

This shift marks a departure from traditional investment models that focused solely on profit maximization, moving toward a more holistic approach that considers long-term sustainability and societal impact.

Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) investing refers to integrating non-financial factors into investment decision-making processes (Eccles et al., 2011).

These factors encompass a wide range of issues, from carbon emissions and labour rights to board diversity and anti-corruption policies. The growing prominence of ESG reflects broader societal concerns about climate change, inequality, and corporate accountability.

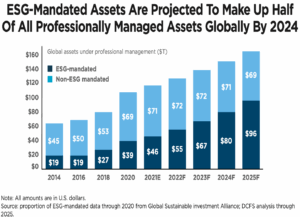

According to PwC (2023), global assets under management incorporating ESG criteria are projected to far exceed $53 trillion by 2025, representing more than a third of total global assets.

While much of this growth has occurred in developed economies, emerging markets are also starting to adopt ESG principles, albeit at varying paces and with differing motivations.

This feature explores the evolving role of ESG in sustainable investing, examining how it influences investor behaviour, corporate practices, and regulatory frameworks. It also highlights the challenges associated with ESG adoption.

It offers insights into how stakeholders can ensure that ESG remains a force for genuine positive change rather than mere marketing and Public Relations rhetoric.

Understanding ESG: Beyond Profit to Purpose

At its core, ESG investing seeks to answer a simple yet profound question: Can companies create value not only for shareholders but also for society and the environment?

Environmental (E) is concerned with how companies manage their ecological footprint, including energy use, waste, and climate risk.

Social (S) is a measure of firms’ behaviour toward staff, clients, and society, encompassing human rights, labour practices, and data protection.

Governance (G) is concerned with corporate leadership, executive compensation, openness, and ethical conduct.

These metrics are often used to quantify a firm’s ability and strength over the long term, aside from conventional finance measures.

A firm with poor corporate governance, for instance, would be more exposed to scandal or litigation, whereas a firm with strong green policies would be immune to climate events (Schroders, 2021).

Investors integrate ESG scores into investment choices, with others screening out low-scoring companies or investing a portion of their portfolio values in high-scoring ESG companies.

The effectiveness of the scores is, however, varied due to multiple approaches applied by different rating firms and a lack of a standard format (Bloomberg, 2024).

Investor Behaviour and the Rise of Conscious Capitalism

Demand for ESG investment is now widespread and is no longer confined only to specialist ethical funds, but is being integrated into investment approaches by pension funds, asset managers, and institutional investors driven by fiduciary obligation and stakeholder demand (Statman, 2008).

Most investors assume high ESG-rated companies automatically deliver better returns without questioning underlying data or comprehending the limits of available ESG metrics.

Furthermore, extensive greenwashing, where companies overstated or manipulated their ESG credentials, has fostered cynicism and uncertainty among investors (Carvalho & Leta, 2022).

In case of a failed disclosure and checking mechanism, ESG investing risks degenerating into a mere labelling exercise, and not a change driver within the real world.

Corporate Response: PR Stunt or Genuine Transformation?

With shifting investor expectations, firms are reshaping their plans to respond to ESG expectations. Some firms have been embedding ESG as a core aspect of their operations by integrating it into their value chains, products and services, and governance procedures.

Others utilize ESG as a reputation management tool or as a compliance tool. Some firms churn out glossy annual sustainability reports with inspirational words and photographs but are thin on tangible action or quantifiable outcomes (Deloitte, 2023). In other cases, firms selectively report good ESG metrics and do not always report weaker performance as much.

Research has proven that firms with genuine ESG approaches perform better than others in the long term. Eccles et al. (2011) found a statistically significant correlation between good ESG and stronger financial performance and hence contended that ESG is a moral responsibility and a source of competitiveness as well.

Policy and Regulation: Setting the Ground Rules

Government policy is another key driver influencing the ESG landscape. Policymakers are pushing for more disclosures on ESG factors with an aim to increase transparency and minimize informational asymmetry in the marketplace.

In Europe, the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) mandates asset managers to disclose how they incorporate ESG into investment decisions.

Likewise, the United States Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has put forward proposed rules that would mandate public companies to report on climate-related risks and greenhouse gas emissions (SEC, 2022).

Conversely, most emerging markets lack a single ESG regulation, so implementation and reporting quality are patchy. Ghana, for example, has advanced with regulations such as the Ghana Stock Exchange’s ESG Reporting Guidelines, but enforcement is lax (GSE, 2021).

OECD (2022) maintains that effective ESG regulation must encompass:

- Systematized disclosure requirements

- Independent audit mechanisms

- Incentives for early adopters

- Fines for inaccurate or incomplete reporting

If these steps are not taken, ESG initiatives might not yield significant outcomes or fail to meet investors’ expectations.

Challenges and Limitations of ESG Integration

Even though ESG is trendy, there are some obstacles:

- Lack of Standardization

There is no globally accepted standard ESG framework. Investors apply institution ratings from MSCI, Sustainalytics, and Bloomberg, which generally have differing reports because methodologies vary (Bloomberg, 2024). The inconsistency makes it harder for investors to make informed decisions.

- Short-Termism vs. Long-Term Value

Most investors continue to be fixated on short-term returns over long-term survival. ESG benefits accrue in the long run, which could be less conflicting with the quarterly profits expectations (PwC, 2023).

- Data Quality and Verification

Good quality ESG data remains scarce, particularly across sectors like agriculture, manufacturing, and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Self-reported numbers are prone to tampering, and third-party audited data are rare in unregulated markets.

- Cultural and Regional Differences

What constitutes good ESG practice in one location may not hold elsewhere. Labour laws, environmental conditions, and governance norms vary significantly across geographies, rendering cross-border comparisons and investments difficult.

Opportunities for True ESG Integration

Despite the challenges, ESG presents opportunities for investors and businesses willing to embrace sustainability as a strategic priority.

- Better Risk Management

Firms that proactively manage ESG risks, such as supply chain integrity or climate resilience, are better positioned to withstand regulatory changes and market shocks.

- Competitive Differentiation

Individuals who have sound ESG credentials tend to have stronger brand, customer, and staff loyalty, which all result in sustainable success.

- Innovation and Market Access

ESG could stimulate innovation since companies will need to produce cleaner technologies, inclusive products, and socially responsible services. It also opens doors for business in emerging markets with tougher ESG demands.

- Impact Investment

Besides risk management, ESG enables impact investing, an investment undertaken to generate quantifiable social or environmental returns alongside financial returns. This is gaining traction in development finance, especially in Southeast Asia and Africa.

Conclusion

The rise of ESG investing represents a fundamental shift in capital allocation and the concept of value in modern capitalism. Financial return is now joined by environmental sustainability, social justice, and ethical management as a determinant of success.

However, it’s not a panacea. Whether ESG succeeds in reshaping industries and saving the planet depends on transparency, accountability, and genuine commitment, not from investors and regulators alone, but also from the firms themselves.

To fulfil its promise, ESG must transcend checklists and public relations efforts. ESG must become part of strategy and be supported by good data and aligned with global sustainability agendas such as the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Only when ESG does so will it produce a more resilient, inclusive, and environmentally conscious economy.

As we enter the climate crisis era of inequality and geopolitical unrest, the role of ESG in sustainable investing will grow ever more vital. Whether it succeeds is up to stakeholders to separate substance from symbolism and to do something with it.

References

Bloomberg. (2024). ESG ratings: A comparative analysis. Bloomberg LP

https://www.bloomberg.com/research/esg-ratings [Accessed May 11, 2025]

Carvalho, F., & Leta, J. (2022). Greenwashing in ESG investing: An exploratory study. Journal of Cleaner Production, 339, 130745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.130745

Deloitte. (2023). Global ESG trends report. Deloitte Insights

https://www2.deloitte.com/global/en/pages/risk/articles/esg-trends-report.html [Accessed May 11, 2025]

Eccles, J. F., Ioannou, I., & Serafeim, G. (2011). The impact of corporate sustainability on organizational processes and performance (No. 11–104). Harvard Business School Working Paper.

Ghana Stock Exchange (GSE). (2021). ESG Reporting Guidelines for Listed Companies. https://www.gse.com.gh [Accessed May 11, 2025]

OECD. (2022). Sustainable finance and ESG investing: Policy considerations. OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd.org [Accessed May 11, 2025]

PwC.(2023). Global ESG trends for business leaders. PwC Global

https://www.pwc.com/global-esg-survey.html [Accessed May 11, 2025]

Schroders. (2021). Understanding ESG investing: A guide for investors. Schroders Investment Management.

Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). (2022). The Enhancement and Standardization of Climate-Related Disclosures for Investors.

SEC.gov. https://www.sec.gov/rules/proposed/2022/33-10982.pdf [Accessed May 11, 2025]

Statman, M. (2008). What investors want: A guide to smart investment choices. McGraw-Hill.

Thaler, R. H. (2016). Misbehaving: The making of behavioural economics. W.W. Norton & Company.

Ebenezer specializes in Development Communication and has research interests in Sustainability, Climate Communication, Development Studies, and Green Economy. Connect with him via: [email protected] / [email protected]

LinkedIn: Ebenezer Asumang. [ https://www.linkedin.com/in/ebenezer-asumang/ ]