Produced by the Center for Applied Research and Innovation in Supply Chain – Africa- (CARISCA)

Contributors: Henry Ataburo, Listowel Owusu Appiah, Nathaniel Boso, Abdul Samed Muntaka

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

This report explores the relationship between tax policies and port operations in Ghana, focusing on how changes in tax regimes affect port traffic and government revenue. Ghana’s ports, particularly Tema and Takoradi, are crucial to the nation’s economy, serving both domestic needs and neighboring landlocked countries.

However, high taxes, especially post-2022, have strained Ghana’s port competitiveness compared to ports of neighboring countries like Togo and Cote d’Ivoire.

Key Findings

- Tax Regimes and Port Traffic Trends: From 2017 to 2019, tax relief measures, such as the Benchmark Value Discount Policy (BVDP), significantly boosted port activity, leading to a noticeable increase in imports, which constitute 66% of overall cargo throughput. However, from 2020 onwards, increased taxes, including a VAT hike and the abolition of BVDP, have led to a decline in port traffic. Notably, the COVID-19 pandemic also affected export traffic in 2020, but recovery efforts saw a resurgence by 2021. Despite this, import and overall cargo throughput have been negatively impacted by increased tax burdens, leading to a 7% drop in exports by 2023.

- Comparative Performance with Neighboring Countries: Ghana faces competition from Togo and Ivory Coast, with Togo surpassing Ghana in container traffic since 2015 due to lower taxes and a more favorable business environment. Togo’s exponential growth in container throughput highlights Ghana’s declining regional competitiveness.

- Tax Revenue Trends: Despite the decline in port activity, Ghana’s overall tax revenue has grown, driven primarily by direct taxes. Customs and indirect taxes have contributed, though, to a lesser extent. The report suggests that, while the government has increased revenue, the high taxes have discouraged importers, reducing port traffic.

- Forecast: The forecast for 2024-2030 predicts a continued decline in import traffic due to rising costs, while export traffic is expected to experience erratic but upward growth. This reflects the potential for Ghana to capitalize on its export sector if favorable policies are implemented.

Conclusion and Recommendations: The report concludes that high taxes, particularly the abolition of the BVDP, have adversely affected Ghana’s port competitiveness. To reverse this trend, policymakers are advised to reconsider tax relief measures, introduce competitive port tariffs, and streamline port processes to reduce hidden costs. Enhanced collaboration with neighboring countries and investment in port infrastructure are also recommended to regain regional competitiveness. Moreover, the report suggests that the government can increase tax revenue from the ports by focusing attention on the efficiency and effectiveness of tax operations, particularly direct taxes.

Introduction

Port and harbor operations contribute to government revenue and constitute a major national asset for economic growth. Ghana’s two major seaports (Tema and Takoradi) are popular in the West African sub-region as they serve as a gateway to neighboring landlocked countries such as Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger. These ports, however, compete with ports in neighboring countries – i.e., Togo and Ivory Coast – for the transit of goods to landlocked West African countries.

It has been contended that the high taxes in Ghana’s ports may explain the low cargo traffic and subsequent decline in government revenue from the nation’s two major ports, following recent tax actions taken by the government. Some have argued that, while Ghana’s neighbors are credited for operating free port regimes, harbors and ports in Ghana are heavily burdened with multiple and high tax rates, which are noted to be contributing to the low cargo traffic observed in the first quarter of 2023.

In this report, we examine how port tax policies by the government of Ghana may have contributed to traffic in Ghana’s major harbors and ports, and the extent to which variations in port traffic may contribute to government revenue from port operations. We examine the historical trends in port operations, government tax revenue, and tax regimes from 2011 to 2023.

The Government of Ghana (GoG) has initiated and implemented several taxes and tax amendments in Ghana since 2001. However, recent tax levies and amendments by the GoG have been considered aggressive by the business community. An extract of tax policies implemented from 2017 to 2023 that have significant implications for port operations is as follows:

Zone 1 (2017 to 2019) – Decreases in tax

- Import duty exemption for the One-District-One-Factor (1D1F) factories, and

- Benchmark Value Discount Policy (BVDP): 30% discount on the value of imported vehicles, and 50% discount on the value of all other imported goods, before applying import duty charges.

Zone 2 (2020 to 2121) – Increases in tax

- COVID-19 levy: 1%-point increase in national health insurance levy (NHIL) and 1%-point increase in value-added tax (VAT).

Zone 3 (2022) – Increases in tax

- BVDP reviewed downward.

Zone 4 (2023) – Increases in tax

- 2.5%-point increase in VAT[1], and

- BVDP abolished.

2.2 Trends in Port Traffic and Tax Regimes

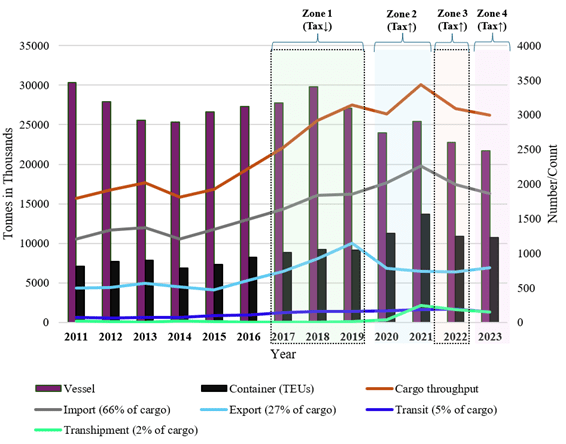

Figures 1 and 2 depict the trends and percentage changes in port traffic (i.e., Vessel call, Container throughput, Cargo throughput, and its decomposition: import, export, transit, and transshipment), respectively, across the four zones of tax regimes. Port operations show an upward/positive trend over the period 2011 to 2023.

Zone 1 (2017–2019): This period is marked by a tax reduction (introduction of the Benchmark Value Discount Policy, BVDP), which coincides with a noticeable increase in cargo throughput, particularly in imports (66% of total cargo). Exports (27%) and transit traffic (5%) also see moderate growth over the period (see Figure 2). Vessel and container throughput both reflect a steady rise during this time, suggesting that the tax relief spurred port activity.

Figure 1. Port Traffic in Ghana | Source: Ghana Ports and Harbor Authority

Figure 2. Changes in Port Traffic in Ghana | Source: Ghana Ports and Harbor Authority

Zone 2 (2020–2021): The tax policies in this zone reflect increases with the imposition of the COVID-19 levy, leading to a slight dip in cargo throughput in 2020. However, imports remained relatively steady, while exports declined sharply due to the global pandemic (-32% in 2020). As the world recovered from the pandemic in 2021, export traffic rebounded with a significant 26% growth. The BVDP appears to have supported this rebound despite the increased tax burden.

Zone 3 (2022): Another tax increase (reduced BVDP discounts) occurred in this period, resulting in a notable decline in import traffic (-12%) and a slower growth rate for exports (4%). Cargo throughput also decreased by 10%, indicating the negative effects of higher import duties on overall port traffic.

Zone 4 (2023): In 2023, the complete abolition of the BVDP and a 2.5%-point increase in VAT led to further declines in cargo traffic (-3%), driven by a 7% drop in exports, even though imports showed some resilience. This suggests that high tax burdens have had a cumulative negative impact on port activity.

- Import traffic is the largest contributor to Ghana’s port throughput, making up 66% of the cargo. Any tax policy that affects imports will therefore have a significant impact on overall port activity.

- Export traffic, though smaller, fluctuates based on both global economic conditions and local tax policies, showing resilience post-pandemic.

- Transit traffic and transshipment remain small but relatively stable, though the latter may be vulnerable to tax changes that increase operational costs.

The decline in port operations in 2020 is mainly attributed to the COVID-19 pandemic, and the subsequent recovery years (2021-2023) highlights the resilience of export traffic. On the other hand, import traffic proved resilient during the pandemic; however, it also proved highly sensitive to government tax policy in the recovery period. In sum, the charts demonstrate a clear relationship between tax policies and port traffic in Ghana. Reductions in taxes (Zone 1) correlate with increased port activity, while tax increases (Zones 2–4) appear to have dampened growth, particularly for imports and overall cargo throughput.

2.3 Comparison of Port Traffic among Neighboring Countries

Ghana shares borders with Cote d’Ivoire and Togo, who compete in serving the landlocked countries in West Africa, and sometimes the domestic markets. Figure 3 compares container traffic in tonnes across the three neighboring countries—Ghana, Togo, and Côte d’Ivoire—from 2011 to 2021. It highlights shifts in port performance and container throughput during this period. Until 2015, Togo’s port operations recorded very low container traffic; however, from 2015 to 2016, all three countries were nearly at par with container throughput of around 800000 tonnes for each country.

Figure 3. Port Traffic among Neighboring Countries | Source: UNCTAD – Container Throughput

Togo experienced a remarkable surge in container traffic in 2015, which had surpassed both Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire by 2017. By 2021, Togo’s container traffic had more than doubled, reaching approximately 2 million tonnes, positioning the country as a leading player in the region.

Ghana gained exponential traffic between 2020 and 2021 – the two years following the introduction of the BVDP – almost in parallel with Togo. Cote d’Ivoire, on the other hand, remained relatively stable throughout the period, with minor fluctuations but no significant growth compared to the other two countries.

The chart in Figure 3 highlights the growing dominance of Togo in container traffic within the region, surpassing both Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire. Ghana, while experiencing growth, may need to reconsider its port fees, taxes, and overall competitiveness to redefine its position in port operations within the region.

Tax revenue in Ghana comes from three major sources, namely, direct tax, indirect tax, and customs tax. Figure 4 shows the trend in tax revenue in Ghana, using data from the GRA, BoG, and UNCTAD, to account for the incompleteness of data from the GRA.

Figure 4. Annual Tax Revenue for Ghana | Source: GRA, BoG and UNCTAD

Data points from 2011 to 2012 from UNCTAD were appended to GRA’s data to produce figures 5 and 6. The two charts illustrate the trends and growth in tax revenue respectively. Both charts are segmented into four tax zones that represent periods of tax policy changes in Ghana. Figure 5 depicts, in addition, trends for sub-tax components: direct tax, indirect tax, and customs tax from 2019 to 2023.

An increasing trend for total government tax revenue is observed from 2011 to 2023. A gentle trend was observed up to the year 2019 and plateaued in 2020, most likely attributable to the pandemic and or the BVDP. Thereafter, tax revenue began to increase exponentially from 2021to 2023. . Customs tax achieved constant growth (38%) between 2022 and 2023. Overall, it is observed that the massive growth in government tax revenue is most likely driven by direct taxes – which accounts for about 48% of total tax revenue. Customs tax and indirect tax contribute about 28% and 24%, respectively, to total tax revenue (Figure 7). Thus, contrary to the notion that the government has been losing revenue due to the introduction of BVDP, the data seem to suggest that revenue growth started peaking during the effective periods of BVDP. Also, the exponential growth (49%) in total tax revenue in 2023 could be attributed to the growth (57%) in direct tax. Customs tax on the other hand, experienced a constant growth of 38% from 2022 to 2023.

Figure 5. Annual Tax Revenue for Ghana | Source: GRA and UNCTAD

Note: Data on direct, indirect, and customs tax are only available for the periods 2019 to 2023.

Figure 6. Changes in Tax Revenue | Source: GRA and UNCTAD

Zone 1 (2017–2019): This period was marked by tax reductions. Revenue growth in this period remains moderate, with the total tax revenue growth rate dropping from 22% in 2017 to 17% in 2018 and 2019. This growth trend was likely driven by policy decisions such as the Benchmark Value Discount Policy (BVDP), which encouraged port activity but restrained customs tax revenue.

Zone 2 (2020–2021): This period saw tax increases, including the introduction of the COVID-19 levy. Despite the pandemic, total tax revenue began to increase significantly, particularly from 2021 with a growth of 26%, as economic recovery efforts and new taxes were introduced.

Zone 3 (2022) and Zone 4 (2023): These periods are characterized by aggressive tax hikes, including the abolition of the BVDP and further increases in VAT. As a result, all tax categories saw sharp growth. In 2023, total tax revenue grew by 49%, with direct taxes leading at 57% growth.

The analysis here reveals that Ghana’s tax revenue has grown significantly over the last decade, particularly from 2020 to 2023, driven largely by direct taxes. Customs and indirect taxes have also contributed to this growth but to a lesser extent. The implementation of higher taxes in recent years, especially during Zones 3 and 4, has accelerated the revenue growth, albeit potentially at the cost of trade activity, particularly imports, as seen in the amendment of the Benchmark Value Discount Policy (BVDP).

Figures 7 and 8 show the time series forecast – from 2024 to 2030 – based on past port traffic (import and export only), and government tax revenue (total and customs tax revenues, only), respectively.

4.1 Port Traffic Forecast for the Period 2014 to 2030

The forecast curve in Figure 7a shows a downward trend, indicating that import traffic will most likely continue to decline in the future. On the other hand, Figure 7b suggests an erratic but upward forecast for export traffic in Ghana. It shows that export traffic will increase exponentially in 2024 before it stabilizes.

Historical Import Trends (2011–2022)

- The green line shows the actual import tonnage from 2011 to 2022. Imports increased significantly from 2013 onwards, reaching a peak in 2021 and 2022 at around 2 million tonnes.

- The data indicate a generally upward trend with some fluctuations, particularly around 2016 and 2017. The peak in imports coincides with post-pandemic recovery and potentially increased demand for goods.

Forecasted Import Trends (2023–2030)

- The orange line forecasts a decline in import volumes from 2023 onwards, with imports expected to decrease steadily through 2030. By 2030, imports are forecasted to drop below 1.5 million tonnes.

- This projected decline could be attributed to factors such as rising import costs, changes in tax policies (e.g., the removal of the Benchmark Value Discount Policy), the poor performance of the Ghanaian Cedi against foreign currencies or increased local production reducing the need for imports.

Historical Export Trends (2011–2022)

- The blue line shows the actual export tonnage. Exports experienced consistent growth from 2011 through 2019, reaching around 1 million tonnes in 2019. However, there are noticeable fluctuations between 2020 and 2022, likely influenced by the global economic disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Forecasted Export Trends (2023–2030)

- The orange line indicates a positive outlook for exports, with export tonnage expected to rise steadily from 2023 onwards, reaching around 1.2 million tonnes by 2030.

- After a period of volatility around 2025, the export forecast shows strong growth, suggesting that Ghana’s export sector will likely benefit from improved global demand, and enhanced production capacity. However, this is contingent on favorable trade policies in the longer term.

The charts suggest that Ghana’s trade dynamics will shift in the coming years, with imports projected to decline while exports show potential for growth. Policymakers and businesses should focus on capitalizing on the positive export forecast while addressing the factors leading to the decline in imports.

4.2 Government Tax Revenue Forecast for the Period 2024 to 2030

Figure 8a juxtaposes the historical and forecast trend for government tax revenue, while Figure 8b suggests trends in historical and forecasted customs tax revenue.

Historical Total Tax Revenue Trend (2011-2022)

- The green line shows a steady growth trend in total tax revenue over the period 2011 to 2023.

Forecasted Total Tax Revenue Trend (2023-2030)

- The orange line shows a positive outlook for total tax revenue from 2023 onwards, depicting an exponential growth in total tax revenue. Noticeably, such exponential growth is most likely to materialize if the experienced performance in direct and indirect tax over the last three years (2021 to 2023) continues within the forecast period.

Customs Tax Revenue (2011-2030)

Historical Customs Tax Revenue Trend (2011-2022)

- The blue line shows an increasing growth trend for customs tax revenue from the historical account.

Forecasted Customs Tax Revenue Trend (2023-2030)

- The orange line depicts the forecasted growth trend through 2030, but at a slower growth rate relative to the historical trend. This is can probably be accounted for by the increasing cost of importation – which accounts for a significant percentage of customs tax revenues.

Ghana’s port operations are a critical asset for the nation’s economy, contributing significantly to government revenue. However, recent tax policies, particularly the introduction and adjustment of the Benchmark Value Discount Policy (BVDP) and subsequent tax increases, have had a mixed impact on port traffic and competitiveness.

From 2017 to 2021, tax reliefs such as import duty exemptions and the BVDP contributed to increased port traffic, notably in import activity. This period saw growth in cargo throughput, helping to sustain port operations during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, post-pandemic, from 2022 to 2023, increases in Value Added Tax (VAT) and the abolition of the BVDP led to a significant drop in port traffic, particularly in imports, which constitute 66% of overall port throughput. The decreased traffic, combined with rising operational costs, has driven local traders to reduce their import volumes and seek alternative ports in neighboring countries such as Togo and Ivory Coast, which operate free port regimes.

Despite Ghana’s recent growth in government tax revenue, largely driven by direct taxes, the high costs of doing business in Ghana’s ports are impacting the country’s competitiveness in the West African region. Cargo throughput has notably declined, and there is increasing reliance on alternative ports by traders from landlocked countries such as Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger.

- Reinstate or Reconsider the Benchmark Value Discount Policy (BVDP):

- The abolition of the BVDP has contributed to reduced import traffic at Ghana’s ports. A revised version of the BVDP, or a similar policy that provides some relief on import duties, could help attract more traffic and sustain revenue from port operations.

- Consider offering targeted tax reliefs for key industries or specific types of goods that are crucial for national development or have strong regional demand.

- Introduce Competitive Port Tariffs to Match Neighboring Ports:

- To remain competitive with neighboring countries such as Togo and Ivory Coast, Ghana should review its overall port fees and taxes. Offering more competitive rates for transit goods and providing incentives for landlocked countries to use Ghanaian ports could reverse the current decline in transit trade.

- Consider reducing or capping port taxes for specific periods, especially for importers who provide significant trade volumes, to regain the trust of local and regional traders.

- Promote Regional Collaboration for Port Competitiveness:

- Ghana can explore regional partnerships with neighboring countries to harmonize port charges and reduce competition for transit trade. Joint marketing efforts with regional trade blocs could also help position Ghana as a premier port destination.

- Invest in infrastructure development at both Tema and Takoradi ports to ensure they can handle larger volumes of traffic and support future growth in West Africa’s trade.

- Develop Alternative Revenue Streams for Ports:

- To reduce reliance on import taxes, Ghana’s ports should explore alternative revenue streams, such as increasing exports, promoting industrial free zones, and providing value-added services like logistics, warehousing, and processing facilities.

- By focusing on enhancing export activity, Ghana can ensure steady port traffic and reduce the impact of fluctuating import volumes on overall port revenue.

- Enhance Customs Enforcement and Monitor Underreporting:

- While high taxes may lead to underreporting of cargo values or smuggling, strengthening customs enforcement and leveraging modern technologies such as blockchain and AI can help prevent tax evasion.

- Providing tax breaks or incentives for businesses that report accurately and adhere to port regulations can encourage compliance and reduce the need for traders to use alternative means to reduce their tax burden.

The future of Ghana’s port operations largely depends on the balance between maintaining government tax revenues and ensuring competitive trade policies that attract importers and exporters. Adjusting tax policies to create a favorable business environment at the ports will be crucial in maintaining competitiveness in the region, especially with the growing threat from neighboring countries. Strategic revisions to existing tax regimes, along with infrastructural improvements and streamlined port operations, will help Ghana regain its standing as a key transit hub in West Africa.

Table 1. Ghana Tax and Tax Amendments Since 2001

Table 1. Ghana Tax and Tax Amendments Since 2001_ continuation

| Year | Actions |

| 2018 | 39. Extension of National Fiscal Stabilisation Levy (NFSL) and Special Import Levy (SIL) to end 2019: as a short-term measure as efforts are made to improve compliance |

| 2019 | 1. Exemption of 1D1F factories from import duty

2. Benchmark Value Discount Policy was introduced in April 2019 by the government to make the Ghanaian ports competitive, reduce smuggling, and increase government revenue from the ports. The policy provided a discount of 50% on the delivery or benchmark values of imports except vehicles. The delivery values for vehicles were reduced by 30% |

| 2020 | 40. Renew and extend the National Fiscal Stabilisation Levy and Special Import Levy (SIL) for another five years to support the Budget |

| 2021 | 1. Introduce COVID–19 health levy

2. 41. The COVID-19 pandemic has caused additional health spending far exceeding the annual health budget. To provide the requisite resources to sustain the implementation of these measures, the government is proposing the introduction of a COVID-19 Health Levy of a one percentage point increase in the National Health Insurance Levy and a one percentage point increase in the VAT Flat Rate |

| 2022 | 1. After two and a half years of operation, the temporal benchmark (discount) policy on imports introduced as a stop-gap measure will be reviewed to make it more efficient and targeted (50%–>30%; 30%–>10%) |

| 2023 | 64. Excise tax reform will include revising the taxation of cigarettes and tobacco products to align with ECOWAS protocols. The reform will also target an increase in the excise rate for spirits above that of beers. There will be taxation of products such as electronic smoking devices and liquids which are not currently taxed

65. The Value Added Tax (VAT) rate will be increased by two and a half percentage points from 12.5% to 15%, the VAT threshold reviewed, and major reforms undertaken concerning VAT exemptions

66. The benchmark discount policy will be fully phased out in 2023 while the Customs Regulations 2016 (LI 2248) will be amended to allow for self-clearing of goods by importers at the ports of entry without recourse to a customs house agent |

Source: Budget statements_ Government of Ghana (2001-2023).

| Year | Vessel | Cargo throughput | Import (66% of cargo) | Export (27% of cargo) | Transit (5% of cargo) | Transhipment (2% of cargo) | Container (TEUs) |

| 2011 | 3465 | 15697476 | 10520064 | 4340698 | 645961 | 189421 | 813494 |

| 2012 | 3185 | 16779659 | 11698319 | 4435019 | 536415 | 82656 | 884984 |

| 2013 | 2917 | 17632640 | 11971628 | 4946156 | 659378 | 55478 | 894362 |

| 2014 | 2891 | 15876268 | 10576489 | 4489223 | 609320 | 197596 | 783737 |

| 2015 | 3039 | 16844662 | 11789204 | 4139739 | 832758 | 129468 | 840595 |

| 2016 | 3122 | 19459834 | 13079082 | 5364815 | 944082 | 71855 | 942463 |

| 2017 | 3175 | 22086626 | 14291927 | 6463773 | 1249336 | 56393 | 1009755 |

| 2018 | 3406 | 25512289 | 16040452 | 8015179 | 1388084 | 68573 | 1056785 |

| 2019 | 3092 | 27520752 | 16248514 | 10001124 | 1363892 | 86813 | 1048377 |

| 2020 | 2737 | 26385923 | 17674236 | 6848094 | 1496822 | 366718 | 1287069 |

| 2021 | 2902 | 30088625 | 19792566 | 6464493 | 1649595 | 2181971 | 1562000 |

| 2022 | 2600 | 27033223 | 17395516 | 6357231 | 1660608 | 1619868 | 1244245 |

| 2023 | 2479 | 26229381 | 16259769 | 6907456 | 1302337 | 1302337 | 1226635 |

Source: Ghana Ports and Harbours Authority

Table 3. Container (TEUs) Traffic among Neighboring Countries

| Year | Ghana | Togo | Cote d’Ivoire |

| 2011 | 813494 | 352695 | 766071 |

| 2012 | 882877 | 288481 | 880104 |

| 2013 | 894362 | 311470 | 983188 |

| 2014 | 793582 | 380798 | 991767 |

| 2015 | 840595 | 905700 | 927379 |

| 2016 | 942463 | 821639 | 885750 |

| 2017 | 1009755 | 1193841 | 907646 |

| 2018 | 1056785 | 1395730 | 924596 |

| 2019 | 1079247 | 1500611 | 994646 |

| 2020 | 1324504 | 1725270 | 988459 |

| 2021 | 1604724 | 1986131 | 1015624 |

Source: UNCTAD database