By Felix Larry ESSILFIE (Dr)

Ghana’s ongoing macroeconomic stabilization efforts, anchored by the International Monetary Fund’s $3 billion Extended Credit Facility program, have drawn attention to the underlying policy dissonance that characterizes its fiscal-monetary governance.

While headline inflation has moderated—from over 50% in late 2022 to 23% by early 2024—this apparent progress belies structural imbalances in the economy, particularly the entrenched pattern of fiscal dominance that continues to impair monetary policy effectiveness.

Fiscal dominance, in both theoretical and empirical terms, reflects a situation where fiscal imperatives subvert central bank autonomy, creating a context in which monetary policy becomes subordinate and unable to deliver sustained price and exchange rate stability.

Ghana exemplifies this policy dysfunction, where even aggressive monetary tightening is rendered ineffective due to persistent budget deficits, quasi-fiscal liabilities, and institutional constraints on central bank independence.

The concept of fiscal dominance can be explored through the analytical lens of three foundational macroeconomic frameworks: the Fiscal Theory of the Price Level (FTPL), the Sargent-Wallace “Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic,” and the open-economy Mundell-Fleming IS-LM-BP framework.

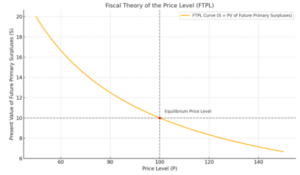

The FTPL posits that the price level is fundamentally anchored not by money supply alone but by the intertemporal government budget constraint—that is, the present discounted value of expected primary surpluses.

As demonstrated in the FTPL curve, a reduction in expected future fiscal surpluses—due to structural deficits or growing debt service obligations—raises the equilibrium price level, even if the monetary authority maintains a constant nominal money supply.

Ghana’s situation aligns closely with this proposition, as the inability to commit credibly to future primary surpluses has continually eroded price stability and currency credibility.

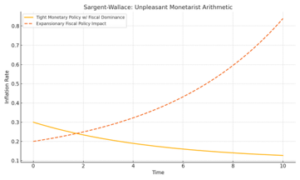

Further insight is gained from the Sargent-Wallace framework, which shows that attempts to tighten monetary policy in a fiscally lax environment are self-defeating. Higher interest rates, while intended to curb inflation, simultaneously increase debt service costs, worsening fiscal deficits. The government, unable to generate sufficient revenue or adjust expenditure quickly, is forced into future monetary accommodation, typically through central bank financing.

The “unpleasant arithmetic” curve illustrates this dynamic: increases in the policy rate result in higher expected future inflation unless fiscal consolidation occurs in tandem. In Ghana, the Bank of Ghana’s elevation of the policy rate to 30%—among the highest in Africa—has not fully anchored inflation expectations, in large part due to the public’s rational anticipation of future monetization of government liabilities.

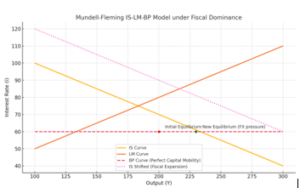

The open-economy Mundell-Fleming IS-LM-BP model further contextualizes Ghana’s vulnerability. In the presence of capital mobility, fiscal expansion shifts the IS curve rightward, increasing income and interest rates, but places pressure on the exchange rate unless the central bank intervenes to maintain stability. In Ghana’s case, such interventions have been costly, involving substantial forex sales and sterilization operations that impair the central bank’s balance sheet.

The divergence between the LM curve (monetary stance) and BP curve (external balance) underscores the incompatibility of simultaneous fiscal expansion and monetary tightening under fixed or managed exchange rate regimes. In practice, Ghana’s current macroeconomic configuration—large fiscal deficits, aggressive monetary tightening, and exchange rate interventions—exemplifies policy incoherence and systemic macro-financial risk.

Empirical data validate these theoretical insights. As of 2023, Ghana’s public debt-to-GDP ratio exceeds 85%, while the fiscal deficit stands at 6.5% of GDP. Domestic debt service absorbs more than half of domestic revenues, creating an unsustainable fiscal position. Between 2021 and 2022, the Bank of Ghana cumulatively financed over GHS 40 billion of the fiscal deficit, contributing to a deterioration in its balance sheet.

This is further compounded by quasi-fiscal operations, including forex market interventions and bailout support for state-owned enterprises, which have diverted the central bank from its core mandate of price stability.

The Bank of Ghana’s participation in the 2023 domestic debt exchange program (DDEP), which resulted in losses exceeding GHS 50 billion, has eroded its capital base and undermined its policy credibility. While the statutory framework nominally guarantees central bank independence, the recurring pattern of overdraft financing and fiscal accommodation reflects a profound de facto subordination.

The effectiveness of monetary policy transmission is further constrained by structural characteristics of Ghana’s financial system. The shallow depth of capital markets limits the pass-through of policy rate changes to real lending rates.

Furthermore, inflation expectations remain weakly anchored across broad segments of the population, particularly in rural and informal sectors where food prices—highly volatile and driven by exogenous shocks—dominate household expenditure.

Although headline inflation has declined, the rigidity of core inflation and the volatility of food and fuel prices have sustained inflation inertia. This condition is further exacerbated by external pressures, including large foreign exchange outflows for debt service and import bills, which maintain continuous downward pressure on the cedi despite high interest rates.

The erosion of the Bank of Ghana’s operational autonomy is perhaps the most critical constraint on monetary credibility. While the Bank of Ghana Act stipulates limits on central bank financing of fiscal deficits, enforcement remains weak. Successive episodes of deficit monetization—often justified by emergency needs or short-term liquidity constraints—have entrenched expectations of fiscal dominance.

Moreover, delayed recapitalization of the central bank following balance sheet losses risks further weakening its signaling power in financial markets. Without a strong and independent monetary institution, inflation expectations become unanchored, reducing the effectiveness of interest rate policy and creating feedback loops that endanger financial stability.

Institutional fragmentation between fiscal and monetary authorities compounds these challenges. Ghana currently lacks a credible, rule-based fiscal framework capable of constraining pro-cyclical expenditure and budget overruns. The absence of a binding fiscal rule allows for politically driven fiscal expansions, often in election cycles, that are not aligned with macroeconomic stability objectives.

Similarly, there is limited institutional coordination between the Ministry of Finance and the central bank, leading to inconsistent policy messaging and reactive, rather than strategic, macroeconomic management.

The lack of a jointly developed Medium-Term Debt Management Strategy (MTDS) integrated with monetary operations further impairs market confidence and contributes to interest rate and exchange rate volatility.

International comparators provide useful lessons. Chile’s implementation of a cyclically adjusted structural fiscal rule has enabled its central bank to operate independently within an inflation-targeting regime, preserving macro stability across political cycles. Brazil, following a period of fiscal dominance and inflation volatility, enacted legislation granting full operational independence to its central bank, which, combined with a well-articulated inflation-targeting framework, restored policy credibility.

South Africa maintains a sound separation of fiscal and monetary responsibilities, with the South African Reserve Bank consistently anchoring inflation expectations due to its legal and operational autonomy.

These cases demonstrate that durable macroeconomic stability in emerging markets is achievable only when fiscal and monetary institutions are mutually reinforcing and underpinned by transparent rules and shared objectives.

For Ghana to achieve similar stability, a recalibrated policy framework is imperative. In the short term, the establishment of a statutory Fiscal-Monetary Coordination Council, co-chaired by the Ministry of Finance and the Bank of Ghana, can ensure quarterly alignment of macroeconomic policies.

Parliamentary enforcement of a zero-overdraft rule for central bank financing, with clearly defined exceptions and transparent reporting, will serve to safeguard BoG independence. Enhancing transparency in central bank operations, including the publication of risk assessments, balance sheet exposures, and forward guidance, can improve market confidence and strengthen the effectiveness of monetary signaling.

Over the medium to long term, Ghana must institutionalize a credible fiscal rule, ideally a cyclically adjusted primary balance rule monitored by an independent fiscal council. This will constrain pro-cyclical spending and provide a predictable fiscal anchor to support monetary policy.

The recapitalization of the Bank of Ghana must be prioritized to restore its balance sheet integrity and policy capacity. Establishing a sovereign asset-liability management framework that integrates debt issuance, forex management, and cash flow forecasting can improve coordination and reduce volatility in interest and exchange rates.

Ghana may also consider evolving its inflation targeting regime into an “inflation-targeting-plus” framework, which accommodates fiscal contingencies and supply-side shocks without undermining price stability objectives.

Complementary reforms in public financial management, including the full deployment of the Integrated Financial Management Information System (GIFMIS) and cash-based budgeting protocols, will help minimize fiscal surprises and enhance macroeconomic planning.

Ghana’s current moment is pivotal. The partial disinflation achieved through monetary tightening risks reversal unless complemented by coherent fiscal discipline and institutional reforms. The persistence of fiscal dominance, quasi-fiscal operations, and central bank subordination not only blunts the efficacy of monetary policy but also erodes investor confidence and weakens the foundation of macroeconomic governance.

To ensure sustainable recovery and long-term economic resilience, Ghana must embrace a new policy architecture—one that is rules-based, institutionally anchored, and strategically coordinated. Such a framework would align fiscal realism with monetary prudence, restore policy credibility, and reestablish the path to macroeconomic stability and inclusive growth.

The writer is the Executive Director, IDER