By Ebenezer NJOKU

“The economy is at a crossroads.” This is no news! After repeated cycles of unsustainable debt accumulation, fiscal distress, high unemployment, below-capacity production and interventions from multilateral institutions, it is not out of place to wonder if it is in any way better off 68 years after gaining independence.

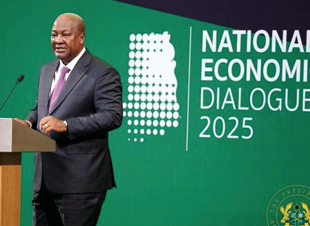

So the question beckons: “Can it finally break free from a pattern of financial dependence and chart a sustainable course for growth?” The recently convened National Economic Dialogue (NED), initiated by President John Dramani Mahama, has been positioned as the platform for changing the country’s economic fortunes. But can a two-day policy summit, no matter how well-intentioned, resolve decades of economic mismanagement and structural deficiencies?

A history of crisis and recurrent dependence

Since independence, Ghana has, not unlike its peers south of the Sahara, developed a reputation for economic volatility. With an average of one International Monetary Fund (IMF) engagement every three to four years, the country has relied more on external interventions than on its own economic resilience.

Ghana officially joined the IMF six months after gaining independence – on September 20, 1957, but its first formal engagement with the Fund occurred in 1965, when it sought financial assistance due to a balance of payments crisis.

Since then, the ‘Black Star of Africa’ has entered 17 different IMF-supported programmes, making it one of the most frequent users of IMF resources in sub-Saharan Africa.

The Structural Adjustment Program (SAP) of the 1980s remains one of the most significant of these interventions. Under the SAP, introduced in 1983, Ghana implemented currency devaluation, trade liberalisation, privatisation of state enterprises, and public sector reforms. While these measures improved macroeconomic indicators in the short term, they also led to job losses, social inequalities, and increased dependence on external financing.

The country has since continued its cycle of IMF engagements:

*1983-1986: Economic Recovery Programme (ERP) under SAP.

*1995-1999: Enhanced Structural Adjustment Programme (ESAP), which sought to deepen liberalization policies.

*2003-2006: Ghana benefited from the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) initiative, securing significant debt relief.

*2009-2012: Extended Credit Facility (ECF) arrangement to stabilise the economy.

*2015-2018: Another ECF programme, following a fiscal crisis caused by excessive borrowing and election-related spending.

*2022-Present: The latest IMF bailout of US$3 billion, intended to address unsustainable debt and restore investor confidence.

This pattern of repeated IMF reliance continues to expose the fundamental structural weakness in the nation’s economic management.

The significance of the National Economic Dialogue

Under the theme ‘Resetting Ghana: Building the Economy We Want Together,’ the NED aims to build consensus among stakeholders—policymakers, business leaders, academics, and civil society—on strategies for economic transformation.

The objective is to devise solutions that will reduce the nation’s dependence on external bailouts and put the country on a path toward fiscal and macroeconomic stability.

The Dialogue’s primary focus areas include:

*Restoring macroeconomic stability through fiscal discipline and debt restructuring.

*Enhancing domestic revenue mobilisation while reducing tax inefficiencies.

*Improving the business environment to attract investment.

*Implementing governance reforms to enhance accountability and reduce wasteful expenditure.

While these themes are promising, they are hardly new. Successive governments have identified similar objectives, yet implementation has remained weak.

The IMF debate: necessary stabiliser or a policy crutch

One of the more contentious topics at the Dialogue is Ghana’s relationship with the IMF. Successive governments has justified previous engagements with the Fund as necessary for stabilising the economy.

However, critics argue that the country’s repeated reliance on the IMF is perhaps the poster for economic mismanagement and overall governance failure.

The benefits of IMF programmes are clear: they enforce fiscal discipline, restore investor confidence, and provide much-needed foreign exchange inflows. However, they also come with trade-offs, including austerity measures that disproportionately affect the most vulnerable populations. More critically, they have failed to provide a long-term fix. The recurrent IMF engagements have failed to yield long lasting results.

This raises a crucial question: Can Ghana implement structural reforms independently, or will it continue to rely on external interventions? If the NED is to have any lasting impact, it must provide a credible alternative to IMF dependence—one that ensures fiscal responsibility without external compulsion.

Of revenue and expenditure

One of Ghana’s most pressing economic challenges is its low revenue-to-GDP (Gross Domestic Product) ratio, which remains among the weakest in sub-Saharan Africa. Despite multiple tax reforms, the government continues to struggle with revenue collection, partly due to inefficiencies, corruption, and a narrow tax base.

Currently, the tax revenue-to-GDP ratio stands at around 13 percent, compared to the African average of 16-18 percent. The reliance on indirect taxation, including VAT, petroleum levies, and the controversial e-Levy, has created a tax system that disproportionately affects lower-income earners while leaving large sections of the economy untaxed.

The NED provides an opportunity to rethink Ghana’s tax structure, shifting focus toward:

*Widening the tax net rather than increasing rates.

*Improving compliance through digitisation and automation.

*Eliminating tax leakages and exemptions, which conservative estimates put the cost to the country at GH¢ 15-25 billion annually.

However, tax reforms alone will not be enough. The government must also address the expenditure side of the equation.

“Ghana does not have a revenue problem, it has a spending problem,” has been a popular refrain and whilst it is a fairly simplistic way to look at it and perhaps, does not capture the entirety of the problem, there is undoubtedly much truth in there.

Public sector wages, interest payments, and subsidies continue to consume a significant portion of government revenue. The fiscal space is constrained, yet there has been limited political will to cut wasteful spending.

In 2022, for instance, interest payments alone accounted for GH¢37.4 billion, nearly 27 percent of total government expenditure. Meanwhile, the compensation of public sector employees consumed another GH¢35.3 billion.

Past reform attempts, such as reducing the size of government or restructuring state-owned enterprises (SOEs), have seen little progress. If the NED is to deliver meaningful outcomes, it must outline clear and actionable measures to rein in government spending.

A few key areas of focus should include:

*Downsizing the bureaucracy to reduce administrative costs.

*Strengthening public procurement processes to minimise corruption-related losses.

*Rationalising government programs to eliminate inefficiencies.

Without addressing the expenditure problem, any revenue reforms will be futile.

The private sector and investment climate

No economic transformation is possible without private sector growth. Ghana’s business environment remains challenging, characterised by high borrowing costs, regulatory bottlenecks, and inconsistent policies.

If the NED is serious about repositioning the economy, it must address critical barriers to private sector growth, including:

*Access to affordable credit, particularly for SMEs.

*Infrastructure development, especially in energy and transport.

*Regulatory clarity, to reduce uncertainty for investors.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows into Ghana have been declining, from US$3.3 billion in 2018 to just US $1.5 billion in 2022, a 39 percent decline from the previous year, According to the United Nations Trade and Development organisation (UNCTAD).

The Ghana Investment Promotion Centre reported a paltry US$650 million in FDIs for 2023 and this came as no surprise as a consequence of the nation’s battered reputation.

Restoring investor confidence is not negotiable and it will require policy consistency and a long-term economic vision.

Political will: The Missing Ingredient?

Undoubtedly, the greatest determinant of the NED’s success will be political commitment. Ghana’s economic instability is not due to a lack of solutions—it is a failure of execution. Too often, economic reforms are abandoned due to political considerations.

The government must demonstrate real commitment to change by ensuring that:

*Recommendations from the Dialogue translate into policy actions.

Economic planning is insulated *from election cycles.

*Fiscal rules are strictly enforced, even when politically inconvenient.

*The rape of the environment under the full glare of the public as a result of illegal mining must stop.

*The constitution must be progressively reviewed and recommendations adopted. Hopefully, this would stem the tide of the winner-takes-all politicking, where the clamour for change is not for the betterment of the nation but for proximity to the coffers.

Without sustained political will, the NED will become yet another symbolic exercise—a platform for discussion rather than action.

So, Ghana’s last bet?

The National Economic Dialogue presents Ghana with a rare opportunity to reset its economic trajectory. But time is running out. If the NED fails to deliver meaningful reforms, Ghana risks deepening its economic dependence and further eroding investor confidence.

The question remains: Will Ghana seize this opportunity, or will it let yet another economic dialogue fade into irrelevance? Posterity awaits.