By Dr. Theophilus ACHEAMPONG

On 7th January 2025, John Mahama of the National Democratic Congress (NDC) party was inaugurated for the third time as President of the Republic of Ghana.

This followed the NDC’s emphatic victory in the December 2024 elections, with President Mahama securing an almost 15 percentage point gap over former Vice President Dr. Mahamudu Bawumia of the New Patriotic Party (NPP). The NDC won 56.42 percent of the valid votes cast compared to the NPP’s 41.75 percent.

Additionally, the NDC secured a large majority in Parliament, winning 183 seats compared to the NPP’s 88. Four other independents have decided to caucus with the NDC, giving it the two-thirds super-majority needed to undertake major constitutional reforms, especially non-entrenched provisions of Ghana’s 1992 Constitution.

The main issues of concern for Ghanaians going into the election, as I indicated in this piece, were the economy and cost of living concerns, jobs, education and roads and infrastructure provision. Others included illegal gold mining (‘galamsey’), health, agriculture and addressing corruption.

Mahama’s economic recovery agenda

President John Mahama’s agenda, as captured in the party’s “Resetting Ghana” manifesto and his inaugural speech on 7th January, has four thematic issues: (1) economic restoration; (2) business environment; (3) constitutional and governance reforms; (4) corruption and accountability. On economic restoration, for example, the government intends to – within the first 90 days in office – scrap the Electronic Transaction Levy (e-levy), COVID-19 Levy, 10 percent levy on bet winnings, and Emissions Levy to alleviate hardships and ease the high cost of doing business.

In this article, I assess the new administration’s economic and tax policy proposals regarding their feasibility, especially given Ghana’s current economic and financial constraints and its participation in a front-loaded IMF programme until 2026.

Economic rebounding

Following the generational economic and financial crisis of the past three years, Ghana’s economy has shown signs of modest stabilisation and rebound. The Statistical Service reported expansions in GDP growth of 4.8 percent in Q1, 7 percent in Q2 and 7.2 percent in Q3, the latter being the highest quarterly GDP growth since 2020. Improvements in mining and quarrying, crops, information and communications, construction and manufacturing activities drove this.

Likewise, inflation averaged 24 percent in 2024 from 39 percent in 2023. However, this was still outside the central bank’s long-term policy target range of 6 percent to 10 percent. Continued gradual disinflation is expected for 2025 and the medium term, which should provide a cushion for households and businesses. IMF projects 2025 real GDP growth of 4.4 percent and 11.5 percent inflation (consumer prices).

Nevertheless, the cedi continues to struggle against its international peers. It depreciated 20 percent against the United States dollar in 2024. The cedi closed the year trading at about 15 cedis to a dollar, down from 12 cedis at the beginning of 2024.

Economic growth should be catalysed, following the successful completion in 2024 of the ‘albatross’ that hung around Ghana’s neck: the external and domestic debt restructuring. Due to the positive debt restructuring and economic rebound, I expect the rating agencies to upgrade Ghana’s sovereign profile in the one-year outlook, improving the prospects of returning to the international capital markets for longer term infrastructure financing.

Given the foregoing, the key issue for the new NDC administration is how to capitalise on this rebounding growth to deliver a diversified economy, particularly in non-extractive sectors like agriculture and manufacturing.

Almost every Ghanaian knows we must diversify the economy beyond gold, cocoa, and oil and gas. This is where the 24-hour economy policy and strategy and the accelerated export development initiative are pivotal to the diversification efforts.

A recent study by a colleague economist at Aberdeen University shows that the 24-hour economy policy could transform the Ghanaian economy, especially on economic growth, labour and welfare. For example, Ghana’s real GDP growth could be 32 percent higher in ten years as compared to a ‘business-as-usual’ scenario in the same time-frame.

Another 3 million jobs could be created within five years of its implementation, with the biggest employment sectors being manufacturing, agriculture, wholesale and retail trade, services, construction and transport.

Nevertheless, major significant supply and demand side incentives are needed to get businesses to operate 24/7 in three shifts of eight hours: tax breaks, cheaper electricity and security, among others.

Monetary reform must also complement this. In this regard, the Bank of Ghana and commercial banks must be encouraged to provide more liquidity to the real sector of the economy to enhance job creation and sustainable economic development. The government’s resort to central bank deficit financing and expensive borrowing on the shorter end of the market via T-bills and other instruments must be minimised.

Likewise, the details of the NDC’s proposed fiscal consolidation plan would be key in assuaging market sentiments. Practical measures on how the government intends to cut down on waste in government spending will be particularly scrutinised. My civil society colleagues have continually advocated for greater emphasis on expenditure quality and value-for-money rather than the over-concentration over the past years on raising revenue.

Lastly, plans to create an Independent Fiscal Council (IFC), reactivate the sinking fund to amortise debt, and more effective oversight of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) are positive and highly welcome. The IMF’s third review of Ghana’s programme in December 2024 notes that the government has submitted a new draft Fiscal Responsibility Act (FRA) to Parliament.

The FRA also provides the legal ground to reform the erstwhile Fiscal Council—established in January 2019 under the Akufo-Addo presidency—to bolster its independence in monitoring fiscal policy, including implementation of the fiscal rules: a long-term fiscal anchor (debt-to-GDP ratio of 45 percent of GDP by 2034) and an operational target (primary balance on a commitment basis).

Tax cuts and trade-offs

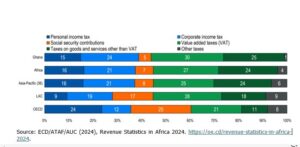

Now, let’s turn our attention to the tax proposals. Ghana’s tax structure—the share of each tax in total tax revenues—comprises taxes on goods and services (55 percent) as the primary source of government revenue, followed by taxes on income, profits and capital gains (40 percent) and other taxes (5 percent). Within goods and services, Value Added Tax (VAT) contributes the highest share of revenue at 30 percent, followed by taxes on goods and services other than VAT at 25 percent—see Figure 1.

As indicated earlier, the government intends to scrap the e-levy, COVID levy, 10 percent levy on bet winnings and emissions levy within its first months. The e-levy raised GH¢1.15billion in 2023, while the COVID-19 health levy amounted to GH¢2.11billion. The betting levy is reported to have raised only GH¢50million. There are no reported figures on the emissions levy yet.

Together, the two items of the e-levy and COVID levy raised GH¢3.26billion (US$296million) in 2023. This was 2.4 percent of total domestic revenue or 0.4 percent of Ghana’s 2023 GDP (Table 1). In context, US$300million is about as much as what the IMF typically gives us for completing a successful review of the ongoing programme (2023-2026). Ghana grants tax exemptions reportedly worth 1 percent to 1.5 percent of GDP annually. Using the upper bound figure, this is US$1.22billion (GH¢17billion) in current monetary terms.

Notes

- The 2.44 percent in the total domestic revenue column is the total receipts from the e-levy and COVID-19 levy divided by the total domestic revenue.

- The 0.39 percent in the nominal GDP column is the total receipts from e-levy and COVID-19 levy divided by the nominal GDP figure.

- Exchange rate of US$1:GH¢11 as at end 2023.

As I have argued on my social media handles, these three taxes can easily be scrapped. It would have a limited impact on public finances but bring significant relief to many citizens and businesses. Reducing tax exemptions, especially for VAT, and improving tax compliance can more than offset these revenue losses.

The former is amply captured in the list of recommendations in the 2022 Tax Expenditure Report of the Ministry of Finance, which calls for a limit or discontinuation of the exemption of local taxes and discontinuation of exemption clauses in commercial contracts, among others.

On the other hand, the emissions levy should stay; but the government should scrap the existing sanitation and pollution levy (SPL) as that amounts to double taxation. As I suggested in another article, we should replace the SPL with an actual tailpipe emission test taken during the annual roadworthiness checks, as done in South Africa and most other countries. Differential tax bands will be applied based on tailpipe emissions above a set threshold—for example, above 120g CO₂ per km— and can also include engine capacity.

Accounting for risks

A larger than anticipated budget deficit in the one-year outlook would likely force the administration to reassess and cut back on planned tax incentives for businesses and cheaper electricity tariffs to drive the 24-hour economy.

Also, proposed measures such as suspending VAT on essential goods like food and fuel would impact Ghana’s fiscal position, especially in the context of the just-concluded debt restructuring and IMF programme. A more comprehensive reform of Ghana’s VAT regime to provide relief for households and businesses is needed rather than ad-hoc tinkering at the edges.

Concluding remarks

Ghana’s business environment has faced challenges, including regulatory hurdles and heightened perceptions of corruption. The new administration must rebuild investor confidence and position the country as a top destination for both local and foreign direct investment that creates sustainable jobs.

President Mahama, with his second term opportunity and no re-election concerns, can fundamentally change Ghana’s governance and socio-economic outcomes for the better.

It has taken the country 32 years and nine regular election cycles to reach the point where citizens have handed any party such an emphatic presidential victory and a super-majority in Parliament. Strong and enduring reforms are a must, as we may never see this again in another generation or so should the opportunity be squandered.

The Mahama administration faces risks and opportunities in maintaining credibility with Ghanaians and creditors and fulfilling its obligations under the IMF-supported programme. The success of Mahama’s agenda will depend heavily on his cabinet selections. The recent nomination of Dr. Cassiel Ato Forson (Finance Minister-designate), John Abdulai Jinapor (Energy Minister-designate) and Dr. Dominic Ayine (Attorney-General-designate) has been largely welcomed by many.

Five key qualities should guide appointments to ensure effective governance and swift policy implementation: competence, technocracy, nation-mindedness and broad political appeal.

————–

Dr. Theophilus “Theo” Acheampong is an economist and political risk analyst with over 15 years of experience in the extractives industry, public financial management and private sector development in frontier emerging markets and academia. Dr. Acheampong holds a PhD in Economics and a Master of Science in Energy Economics and Finance from the University of Aberdeen, United Kingdom. He is studying for a second Master’s in taxation at Oxford University, United Kingdom. Theo has published widely on different academic, policy and media platforms. He is a regular public commentator on several international and local media.