By Kwame Asamoah

In all my years in the cocoa-chocolate sector, one of the most frustrating observations I’ve made is how reverse psychology is often employed in bad faith. It’s used to justify reactionary moves and political rhetoric, all while exploiting the public’s lack of awareness about our underlying mistakes and ineptitude.

This is what inspired me to start writing. Recently, news broke that Ghana has ended a 32-year tradition of seeking international loans to finance its cocoa purchases. However, the story is more complex than it appears. While some reports suggest that COCOBOD, the entity responsible for cocoa in Ghana, has boldly decided to ditch international loans in finance the 2024/2025 cocoa season, others asserted that COCOBOD’s $1.5 billion loan request was rejected by international banks, forcing them to seek alternative funding.

So in this article I will explain to you what the Syndicated loan and the history of seeking international loans to finance our cocoa beans

The genesis of the syndicated loan

To understand COCOBOD’s financial decisions, it is essential to first understand the role of syndicated loans. A syndicated loan is a type of financing where multiple lenders come together to provide funds to a single borrower, typically used for large-scale projects where the required amount exceeds the capacity of a single lender. While such loans can be sourced domestically or internationally, Ghana has historically focused on raising syndicated loans from international sources, particularly in the cocoa sector, due to the significant capital required and the global nature of the trade.

In the context of Ghana’s cocoa industry, COCOBOD annually raises syndicated loans to finance the purchase of cocoa beans. The process involves negotiating with a consortium of international banks to secure the necessary funds. Once an agreement is reached, the loan is syndicated, meaning that a group of banks commits to providing portions of the total loan amount, thereby sharing the risk and reward.

Local banks in Ghana also play a crucial role, sometimes contributing to the loan and most times managing transactions, ensuring the funds are available when needed, and supporting the purchase of cocoa beans during the harvest season. This process has been vital for maintaining liquidity in the sector, allowing COCOBOD to buy cocoa beans from farmers at stable prices, which in turn supports the livelihoods of these farmers and sustains the industry’s growth.

Why were they taking loans in the first place?

Ghana’s reliance on syndicated loans, particularly in the cocoa sector, is primarily driven by the need to secure large amounts of capital quickly and efficiently to finance the purchase of cocoa beans during the harvest season.

The seasonal nature of cocoa production requires significant upfront funding to ensure that COCOBOD can purchase beans from farmers at prices determined by Ghana Cocoa Board (not the farmer ie. Being the regulator, buyer and price determiner. Doing the exact colonial commodity market practices we seek to stop). The large scale of these financial requirements often exceeds the capacity of domestic banks alone, making international syndicated loans a practical solution.

Moreover, by opting for syndicated loans, Ghana can access a wider pool of financial resources, tap into favourable interest rates, and share the risk among multiple international and local financial institutions.

This diversified risk is particularly important in a sector as volatile as agriculture, where market prices can fluctuate widely. The international nature of these loans aligns with the global trade of cocoa, enabling COCOBOD to maintain a steady flow of capital to support the entire Ghanaian value chain from production to export.

Another key advantage for COCOBOD in seeking syndicated loans from international sources is the benefit they gain from the depreciation of the Ghanaian cedi against the U.S. dollar. When COCOBOD secures a loan in dollars, they purchase cocoa beans from farmers in Ghana cedis.

Given the historical average depreciate rate of the Ghana Cedi by about 20% year on year since 1992, the value of the Ghanaian cedi tends to depreciate against the dollar. This depreciation means that, over time, COCOBOD needs fewer dollars to buy the same amount of cocoa beans in cedis, as the local currency loses value. It’s kind of robbing Peter to pay Paul. In this case peter is the farmer. So cocoa beans are bought from farmers a reducing when currency depreciation and inflation are factored into it producer price.

Since COCOBOD repays the loan in dollars and sells the cocoa beans internationally (often receiving payment in dollars or the Ghana Cedi equivalent), they effectively protect themselves from exchange rate or forex-related losses.

In fact, the depreciation of the cedi works in their favour, allowing them to generate more cedi revenue from their dollar sales while having to pay less in dollar terms for their local purchases. This exchange rate advantage allows COCOBOD to accumulate more money, which can be used to cover interest payments on the loan or to reinvest (if they want to, you know what I am talking about) in the cocoa sector.

If COCOBOD were to source these funds locally in Ghanaian cedis, they would avoid forex issues, but the high-interest rates in Ghana would make this approach unsustainable. I would want to even believe that they may have a hedging insurance in place to ensure they don’t fall prey to the effects of the Ghana Cedi depreciation. The large scale of financing required by COCOBOD, often in the billions of dollars, would drive up local interest rates due to increased demand for loans.

This would significantly increase the cost of borrowing, making it more expensive than the benefits they could gain from the depreciation of the cedi. Thus, by borrowing internationally, COCOBOD not only secures lower interest rates but also capitalizes on currency depreciation to enhance their financial position, making it a more strategic and sustainable choice for the organization.

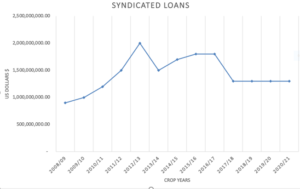

Source: Authour’s Calculation (Raw data from Ghana Cocoa Board)

Lastly, our pursuit of international loans is more of a political manoeuvre than an effort to prioritise farmers’ interests. The cocoa syndicated loan represents one of the largest actual inflows of U.S. dollars into the Ghanaian economy (Billions), which temporarily boosts the supply of dollars and helps stabilise the cedi, even if only slightly and temporarily. This political interest often takes precedence when seeking these loans.

For the Bank of Ghana, maintaining foreign exchange reserves is crucial for supporting imports necessary for economic growth, such as the machinery needed to start factories that are expected to drive economic benefits for the country or the oil we need for our energy needs. But that’s a discussion for another day.

A closer look at the purported shift

Ghana Cocoa Board is still seeking international Loans: Despite claims that COCOBOD is no longer seeking international loans, it’s important to clarify that the loans they are now seeking from traders are still international in nature. These traders are global companies, and any financing they provide would likely be sourced from international financial markets.

These companies (Olam, etc) are foreign entities. Therefore, the assertion that COCOBOD has made a bold shift away from international financing is misleading. The truth is, the funds still originate from international sources, albeit through a different channel.

Prefinancing vs. Loans from Traders: What’s Really Happening?

There seems to be confusion between prefinancing and loans from traders. Prefinancing refers to receiving payment for future cocoa deliveries upfront, similar to the forward sale agreements COCOBOD already engages in.

This approach is more advantageous because it doesn’t involve interest payments, or the power dynamics associated with traditional loans. Offcourse it has its setbacks which includes agreeing to prices which may likely change (not in your favour) hence preventing cocoa board from benefiting from increased current prices.

If COCOBOD is indeed moving towards prefinancing, it might not be as revolutionary as it sounds but rather a reshuffling of existing practices. However, if COCOBOD is treating these as loans, it risks increasing the influence of these traders over Ghana’s cocoa market.

A reactionary decision, not a strategic shift

The narrative of COCOBOD breaking free from international loans might seem like a strategic move, but evidence suggests it’s more reactionary. Reports that COCOBOD’s loan request was rejected indicate that this decision may have been forced upon them rather than being a planned shift.

Furthermore, statements from the Daily Graphic describing this as a “temporary measure” further undermine the idea of a long-term strategic change. It’s likely that this situation arose because international lenders are becoming wary of COCOBOD’s ability to repay loans, especially as cocoa production—and therefore the collateral for these loans—declines. What’s being presented as a proactive strategy might actually be a necessary response to a loss of financial credibility.

The Conflict of Interest: Ghana Cocoa Board as Judge and Jury

One of the core issues is COCOBOD’s dual role as both regulator and market participant. This conflict of interest can lead to situations like the current one, where COCOBOD’s financial practices come under scrutiny.

If the private sector managed cocoa buying and selling, while COCOBOD focused solely on regulation, farmers might feel more protected and assured that their interests are being safeguarded by Ghana Cocoa Board rather than Ghana Cocoa Board being a part of the problem. However, the government’s deep economic interest in cocoa, which is a significant source of foreign exchange, makes it unlikely that COCOBOD will relinquish its control and the continuous sourcing of loans internationally.

This concentration of power has led to inefficiencies and vulnerabilities, such as the current loan rejection. Ghana Cocoa board should focus on rigorous meticulous regulations not buy/selling.

The dangers of COCOBOD’s semi-autonomous status

COCOBOD’s semi-autonomous status under the ministry of finance and economic planning (why not the ministry of agriculture) complicates its role further. Unlike other government agencies funded by taxpayers, COCOBOD generates its own funds, primarily through deductions from cocoa farmers.

This structure incentivizes COCOBOD to focus more on revenue generation rather than effective regulation. As long as COCOBOD continues to operate this way, it will prioritise its role as a buyer and seller over that of a regulator, perpetuating conflicts of interest and financial inefficiencies. The absence of an independent regulatory body to oversee COCOBOD’s operations exacerbates these issues, leading to situations where loan rejections and financial mismanagement come into play and it has to be a government issue to deal with.

Financial Inefficiency and the Need for Reform

The financial data from Ghana Cocoa Board’s (COCOBOD) annual reports from 2012/13 to 2018/19 paints a concerning picture of the organization’s financial efficiency and operational effectiveness. As the sole legal buyer and seller of cocoa beans in Ghana, COCOBOD plays a crucial role in the country’s economy. However, the consistent pattern of losses and fluctuating profits across these years raises serious questions about the competence and management of COCOBOD.

Source Authour’s Calculation (Raw Data from Ghana Cocoa Board’s available financial reports on its website)

Between 2012/13 and 2018/19, COCOBOD recorded significant losses in multiple years despite receiving substantial syndicated loans from international sources. For instance, in 2012/13, COCOBOD recorded a loss of GH¢150 million despite having a sales turnover of GH¢7.88 billion.

This the said in their financial report as being attributed to a decrease in production and lower sales prices. However, the persistent losses in subsequent years, such as GH¢199.4 million in 2015/16 and GH¢394.8 million in both 2016/17 and 2018/19, suggest that the issues go beyond external factors like production volumes and market prices.

In a typical competitive market, companies that experience consistent losses over multiple years are forced to make significant changes—whether in leadership, strategy, or operations—to correct course. Yet, COCOBOD’s recurring losses indicate a lack of effective response to these financial challenges.

This raises concerns about the financial efficiency and accountability within the organization. Unlike private companies, which face the pressure of competition and regulation to remain profitable, COCOBOD operates as a monopoly in the cocoa sector. This monopoly status may contribute to a lack of urgency in addressing inefficiencies, as COCOBOD does not face the same market pressures as private entities.

The role of COCOBOD as both the regulator and the primary market player creates a potential conflict of interest. While COCOBOD is supposed to act in the best interest of the farmers and the broader economy, its operational inefficiencies and financial losses suggest that it may not be fulfilling this mandate effectively.

The lack of a separate regulatory body to oversee COCOBOD’s operations further worsens this issue. In most sectors, regulators exist to ensure that market players operate efficiently, fairly, and in the public interest. However, in the case of COCOBOD, there seems to be no such oversight, allowing the organisation to continue its operations without sufficient checks and balances.

Moreover, the reliance on international syndicated loans, while beneficial in some respects, does not seem to address the underlying issues of financial mismanagement. These loans provide COCOBOD with the liquidity needed to purchase cocoa beans upfront, but the persistent financial losses suggest that the problem lies not with the source of the funds but with how these funds are managed and utilized. At worse, it leads to moneys meant to be given to farmers, paid to international lenders as interes.

To Conclude, The recent developments surrounding COCOBOD’s financing strategy show deeper issues within the organisation. While the move away from international syndicated loans might seem like a bold, strategic decision, the reality appears to be more reactionary, driven by financial constraints and a lack of immediate viable alternatives.

Seeking loans from your buyer puts back power into the hands of the buyer, hence weakening your negotiation power in the process. COCOBOD’s dual role as regulator and market player, combined with its semi-autonomous status, has created a system where financial inefficiency and conflicts of interest are inevitable. Until these structural issues are addressed, COCOBOD’s ability to effectively manage Ghana’s cocoa sector will remain in question. The problem isn’t just where the money comes from—it’s how COCOBOD operates within the system it controls.

Email: [email protected]