By RICHMOND AKWASI ATUAHENE (Dr)

This study reviewed the effects of macroeconomic instabilities, bank specific factors; other industry factors and high fiscal deficits over the years have influenced the up-tick of non-performing loans of the Ghanaian banking industry over period 2014-2023.

The recent IMF Country report 24/030 (01/2024) has confirmed that the government had accumulated significant arrears in both energy and non-energy sectors in the past decade.

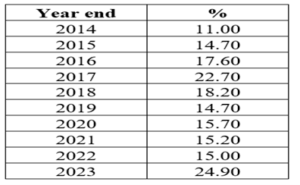

At end December 2023, NPLs were estimated at 24.9 percent and several banks, including systemically important domestic banks and subsidiaries of reputable international banks, reported higher NPL ratios in the range of 20–40 percent.

The stock taking exercise conducted by IMF/BoG assessed an overall stock of arrears at end-2022 broadly consistent with initial program assumptions, with energy sector arrears amounting to some US$ 1.6 billion (2.3 percent of GDP) and non-energy sector arrears at about GHS 35 billion (5.8 percent of GDP) and all energy sector and non-energy sector arrears had all translated into the higher non-performing loan ratios over the past decade (IMF Country report 24/030 (01/2024).

The study reveals that until the government pays off all legacy debts to non-energy and energy sector, and also address the macro-economic instabilities, high fiscal deficits while banking sector deals with poor credit risk management practices and weak corporate governance practices, banking sector could not improve the endemic high non-performing loans in the sector.

The study recommends that the Government of Ghana and Bank of Ghana must be committed to promoting a strong, stable, and viable banking industry to support robust macro-economic growth in terms of stable exchange rate, lower inflation, lower policy rate, lower fiscal deficits, positive terms of trade and manageable public debts. Without a long macroeconomic stability, the Ghanaian banks cannot reduce the endemic non-performing loans in the banking sector which have bedeviled the industry for the past decade.

Second, the government should address the persistent fiscal weaknesses that have created vulnerabilities in the banking sector, particularly rising NPLs over the past decade. To ensure safeguarding financial system stability the government must repay all outstanding legacy debts related NPLs and resolve problem banks or re-fence the arrears.

The government’s dominance in economic activity, against the backdrop of weaknesses in fiscal management, further increases vulnerabilities in the banking sector. Thirdly, the study further recommends that the Ministry of Finance and Bank of Ghana must work hard to address the fully-fledged crisis and the systemic nature’, as the ratio of non-performing loan ratio to total assets in the banking system of 16.97% exceeds that of the globally acceptable ratio of 10% (Demirguc -Kunt and Detragiache (1998).

The study’s conclusion is based on a thorough analysis of the phenomena and considers the implications of the evaluated relevant literatures. The central bank must introduce a roadmap to reduce bad loans in the banking sector as per the Demirguc -Kunt and Detragiache (1998) prescription. Bank of Ghana must aim the NPLs to less than 10% by the end- December 2025.

The financial system is a critical part of the economy of any nation. For a country such as Ghana, its financial system is very important to the realization of the high aspirations for socio-economic development of its people. Ghana’s financial system is made up of many financial institutions.

The Ghanaian financial system has grown substantially during the past years, with total assets reaching 54 percent of GDP 2019. The banking sector is a keystone of any financial system. The smooth functioning of the banking sector ensures the healthy condition of an entire economy.

In the process of accepting deposits and lending, loans banks create credit. The funds received from the borrowers by way of interest on loan and repayments of principal are recycled for raising resources. However, internal controls and risk management practices of banking institutions have not always kept up with the industry’s growth, as evidenced by a steady increase in nonperforming loans during the past years and, more recently, several high-profile banking failures in 2017-2019 IMF selected papers (2019).

These include banks, other deposit-taking institutions (such as savings and loans companies, rural and community banks, micro finance institutions), finance houses, and others such as insurance companies, stock brokers and investment fund managers, and credit unions in the country.

Of these, banks play a significant role as they hold over 75% of the total assets of the financial system. It is therefore incumbent on banks and their stakeholders to understand their critical role in the Ghanaian financial system and the economy as a whole.

As financial intermediary, the banking sector is unquestionably a crucial system for running any economy, and any banking sector’s performance is crucial for encouraging investments and boasting economic growth (Menicucci & Paolucci, 2021).

The financial system influences economic development through its impact on choices related to saving and investment, risk management, efficient distribution of funds, and facilitation of transactions. Banking system also is an important entity of monetary policy, where savings are channeled into investment, thereby supporting economic growth of the country.

The banking sector plays a pivotal role in sustaining the financial system in nations with bank-centric economic structures. Consequently, the banking sector largely dominates the financial market in Ghana.

The rising demand for loans, and banks’ eagerness to meet these demands by assuming higher risks, elevates the likelihood of loans turning into Non-Performing Loans (NPLs). A major challenge facing the Ghanaian banking sector is the prevalence of non-performing loans (NPL) over the past decade. This has been identified as a factor that limits the effectiveness of the banking sector in promoting the growth of the country.

Growing non-performing assets have been a recurrent problem in the Ghanaian banking sector was due to macroeconomic instabilities such as higher interest rates, higher inflation, unemployment, persistent depreciation of the local currency, high fiscal deficits and accumulation and non-payment of arrears due to contractors and service providers on time by the ministries, agencies and departments as well as bank specific factors including poor credit risk management, irresponsible lending, poor supervision and weak governance poor underwriting skills, weak credit reference processes and weak understanding of the sectors where the banks were involved in lending, for example in the areas of financing the local buying agencies in the cocoa industry Non-performing loans (NPLs) erode the profitability and can threaten the solvency of banks, and when a sufficiently large volume of loans is affected, they can potentially threaten financial sector stability. However, building up of non-performing assets (NPLs) disrupts this flow of credit. It hampers credit growth and affects the profitability and solvency of the banks as well.

NPLs are the leading indicators to judge the performance of the banking sector. High ratio of non-performing loans to total loans impacts banks’ lending in several ways. A bank plagued with a high stock of NPLs is likely to prioritize internal consolidation and improving assets quality over provision of new credit.

A high NPL ratio requires greater loan loss provisions, reducing capital resources available for lending and denting bank profitability. Loan loss provision is the amount of money that a bank must set aside as protection against expected credit losses in their loan portfolios (Jia 2024; Lee et al. 2024; Dal Maso et al. 2022). Loan loss provision is the most significant and important accounting accrual in the banking industry (Bushman and Williams 2012). Loan loss provision is important to accounting standard setters because overstated loan loss provision affects the transparency of reported accounting numbers.

It decreases earnings quality and financial reporting quality (Nicoletti 2018). Loan -loss provision is also important to bank regulators and bank supervisors because understated loan loss provision will be insufficient to cover expected credit losses and it can increase bank fragility. High levels of non-performing loans- those in or close to default – are a common feature of many banking crises.

The literature acknowledges that high NPLs impair bank balance sheets, depress credit growth, and delay recovery from crises (Aiyer-et-al, 2015; Kalemli-Ozcan -et al, 2015; IMF, 2016). NPL is a major banking threat for almost every country in the world because they adversely affect the financial stability and profitability of the banking system. NPL can weaken the balance sheets of banks and other financial institutions, reducing their ability to lend and increasing the cost of borrowing. It can lead to a credit crunch, where businesses and individuals find it difficult to obtain financing, leading to a slowdown in economic activity.

The country’s government must spend inefficient tax money to save the banks and financial institutions from financial crises due to the high levels of non-performing loans (NPLs) in the banking sector. Such a wasteful use of tax money restricts government spending on development and has unfavorable indirect effects on the entire economy [1]. On the economic side, NPLs can have several negative effects. First, they can reduce credit avail- ability, making it more difficult for businesses to invest in new projects and expand their operations. It can lead to lower productivity and slower economic growth.

Second, NPLs can reduce confidence in the financial system, leading to capital flight and further tightening credit conditions.

Third, NPLs can lead to a loss of trust in the banking sector, which can reduce the willingness of individuals and businesses to save and invest, further slowing economic growth. A significant build-up of non-performing loans has frequently been linked to the occurrence of banking sector failure brought on by insolvency (Sitepu et al., 2023).

Increasingly, macroeconomic instability in emerging market economies like Ghana, as well as in more mature industrial economies, has been associated with serious problems in the financial sector. The macroeconomic costs imposed by financial sector problems have been very large in terms of forgone growth, inefficient financial intermediation and impaired public confidence in financial markets.

A major challenge facing the Ghanaian banking sector was the prevalence of non-performing loans (NPL) over the past decade. This has been identified as a factor that limits the effectiveness of the banking sector in promoting the growth of the country.

Growing non-performing assets have been a recurrent problem in the Ghanaian banking sector was due to macroeconomic instabilities such as higher interest rates, higher inflation, unemployment, persistent depreciation of the local currency, high fiscal deficits and accumulation and non-payment of arrears due to contractors and service providers on time by the ministries, agencies and departments as well as bank specific factors including poor credit risk management, irresponsible lending, poor supervision and weak governance poor underwriting skills, weak credit reference processes and weak understanding of the sectors where the banks were involved in lending, for example in the areas of financing the local buying agencies in the cocoa industry. Other industry factors such as weaknesses in the legal, regulatory and judicial systems have all contributed to the uptick in non-performing loans in the banking sector over past decade. Protracted legal disputes, persistent adjournment in credit related cases by courts and weaknesses in the Borrowers and Lenders Act 2020 (Act 1052).

Over the past decade, the macro-economic factors, bank specific factors and industry factors have all contributed the fully fledged banking crisis due to up-tick in the high non-performing loans in the banking sector Demirguc-Kunt and Detriagache (1998). The recent economic and financial crises have been the focus of the attention of professionals and academics due to their essential economic consequences.

These crises have arisen mainly due to the increase in NPL in the banking system since, by eliminating the structural profitability of banks, they are forced to limit credit in the system. Financial entities that operate in stable, well-regulated markets and with acceptable levels of economic growth do not usually have high NPL rates.

NPLs can have various causes, including the following factors: Economic downturns and fluctuations in interest rates can exert significant pressure on borrowers, making it increasingly challenging for them to fulfil their loan obligations. The main source of income of banks is through the interest earned on loans and advances and repayment of the principal. If such assets fail to generate income, then they are classified as non-performing loans (NPL). High fiscal deficits over the period had led to high interest rates and engendered a further deterioration in bank assets, profits, and capital. The high fiscal deficits of 15.2% in 2020; 12.2% in 2021; 9.3% in 2022 and 7.7% in 2023 posed some challenges and prospects of creating the fiscal space in the near term are uncertain as the potential for expenditure overruns were high ahead of the 2016 and 2020 elections. Inability to reduce or contain fiscal deficits have compounded the legacy debt to non-energy and energy sectors that had negatively impacted on the non-performing loan ratios. Ghana’s fiscal deficits and its effects on price stability and output growth have been a major source of concern to various governments in the past,

Central Bank of Ghana, the private sector, civil society, domestic and international investors and other major international financial institutions like the IMF, the World Bank and Rating Agencies among others. Fiscal deficits picked up from 6.3 percent of GDP in 2015 to 7.8 per cent of GDP in 2016.

Though it declined to 5.9 percent of GDP in 2017 against a program target of 6.3 percent of GDP, it significantly ballooned again to 7.2 percent of GDP in 2018 against a revised program target of 4.4 percent of GDP in consultation with the International Monetary Fund. Various governments in the past including the current government had to deal with the negative the plaque of fiscal deficits financing and its negative consequences on other macroeconomic variables particularly on inflation in the Ghanaian economy (Osei, and Olawale Oguloka, (2022).

2.0 Theoretical literature on determinants on non-performing loans

Numerous studies on NPLs have exclusively concentrated on three sources of determinants; macroeconomic, bank specific and industry factors are responsible for the changes in NPLs of banking institutions. When a borrower defaults on a loan and fails to pay. In the literature, determinants of NPLs have been categorized into macroeconomic factors, bank-specific factors, and those caused by debt crises. NPLs and its interactions with macroeconomic performances are grounded in theoretical business cycle models with an explicit role for financial intermediation (Williamson, 1985). Naturally, discrepancies in financial regulation and supervision affect banks’ behaviour and risk management practices which are important in explaining cross-country differences in NPLs. The macroeconomic environment inevitably influences borrowers’ balance sheets and their debt-servicing capacity. Thus, adverse economic shocks coupled with high cost of capital and low interest margins (Fofack, 2005) have been identified to cause NPLs.

According to Goldstein and Turner (1996), build-up of NPLs is mostly attributed to a number of factors which include economic downturn, macroeconomic volatility, terms of trade deterioration, high interest rate, excessive reliance on overly high-priced inter-bank borrowings, and moral hazard make monthly principal and interest payments for a predetermined amount of time, the loan is considered non-performing (NPL).

According to Demirgüç-Kunt and Detragiache (2002), regulatory authorities tend to emphasize micro–macro prudential regulatory frameworks for banking stability more than they do on institutional and governance factors that affect financial reporting quality are out of money or face other obstacles, the loan becomes non-performing.

In a later development on the association between NPLs and real growth of GDP, Dimitrios et al. (2016) found that there is a positive link between these two variables. Data employed in their study was quarterly data for the year 1990 to 2015 of fifteen Euro-area countries.

Their findings are consistent with Beck et al., (2015) who found that real growth of GDP, exchange rate, lending interest rate and share prices have significantly influence on the ratio of NPL. According to Taswan et al. (2023), banks often categorize loans as non-performing when principal and interest repayments are past due for more than 90 days or in accordance with the parameters stated in the loan agreement. Once a loan is labeled as non-performing (NPL), there is far less chance that it will be repaid. Even so, a borrower who has already had a debt declared non-performing may begin to make repayments on it. The non-performing loan turns into a re-performing loan in these circumstances (Jolevski, 2017).

Bank-specific factors and country-specific (macroeconomic) factors. Keeton and Morris (1987) proposed that not only local economic conditions influence the loss rates of banking institutions, but bank-specific factors such as risk-taking behaviour and credit management contribute to the loss rates.

In their seminal work, Berger and De Young (1997) examined the link between loan quality, cost efficiency, and bank capital by using a sample of US commercial banks by testing four hypotheses concerning the direction of causality. These include bad luck, bad management, skimping, and moral hazards. Berger & De Young (1997) argued that the bad management hypothesis suggests that low-cost efficiency will develop before or because of rising NPLs.

This is justified by the relationship between management quality and awareness of credit scoring, collateral valuation, and borrower monitoring. The issue of NPLs has been a major area of concern for the lenders and the policymakers. Various research studies have been made to understand the causes contributing to the rise in NPLs, measures that should be taken to resolve the issue in its nascent stage and reforms that have come into effect to reduce the piling up of NPLs.

Factors driving NPLs fall into two broad groups: macroeconomic conditions (such as inflation, interest rate and real GDP growth) and bank-specific factors (capital ratios, quality of risk management). Low GDP growth stands out as a key driver of NPLs.

Numerous studies on NPLs have exclusively concentrated on two sources of determinants that are responsible for the changes in NPLs of banking institutions: bank-specific factors and country-specific (macroeconomic) factors. Keeton and Morris (1987) proposed that not only local economic conditions influence the loss rates of banking institutions, but bank-specific factors such as risk-taking behaviour and credit management contribute to the loss rates. Espinoza and Prasad (2010) investigated NPLs determinants for 80 banks in Gulf Cooperation Council from 1995 to 2008. They revealed that NPLs in these sample banks are determined by both macro-factors and bank-specific factors.

GDP and interest rates appeared to be the dominant macro-factors, while capital size, credit growth and efficiency were found to be the significant bank-specific factors. In addition, they also found that the conditions of global financial market have an influence on the NPLs of these sample banks. Louzis et al., (2012) investigated the factors that drive NPLs in nine biggest banks in Greece employing quarterly data 2003 to 2009.

Analysis was done on three categories of loans: consumer loans, business loans, and mortgage loans. They found that real growth of GDP, unemployment rate, public debt, and the lending rates do influence NPLs of banks.

The effect of these determinants on NPLs depends on loans categories. Specifically, consumer loans were most sensitive for changes in lending rates, business loans to the real GDP growth, and mortgage loans were the least sensitive to changes in macroeconomic variables.

With respect to bank-specific determinants, their results indicate that these determinants’ effect on the NPLs varies between different categories of loans. Among macroeconomic factors, economic growth, interest rates, inflation, unemployment, and exchange rates have been significant (King and Plosser, 1982; Bernanke and Gertler, 1999).

Numerous studies conclude that NPL increases when the economic environment deteriorates (Cifter et al., 2009; Ali and Daly, 2010; Louzis et al., 2012). For example, Mitrakos and Simigiannis (2009) analyzed the relationship of certain macroeconomic factors with the likelihood of debt default in Greece. They found that unemployment and income level are highly correlated with the probability of debt default. Espinoza and Prasad (2010) used a sample of 80 Gulf Cooperating Council entities (Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates) from 1995 to 2008. they concluded that the NPL increases as economic growth decreases and interest rates rise.

Ali and Dali (2010) conducted a comparative study of the U.S. and Australia from 1995 to 2009. They determined that the main factors affecting NPL were gross domestic product (GDP), interest rates, industrial production, and total indebtedness and bank-specific factors on NPLs in 14 Eurozone countries, spanning from 2000 to 2008.

They found that there is a strong correlation between NPLs and these two categories of determinants. Capital adequacy ratio, which represents risk-taking behavior of banks, was found to be statistically negative significant on NPLs.

Using a sample of 85 banks from Italy, Greece, and Spain for the period 2004 to 2008, Messai and Jouini (2013) found that the growth of GDP and banks’ profitability have negative influence on the NPLs, whereas, the rate of unemployment, real interest rates, and credit quality affect NPLs positively. In a later development on the association between NPLs and real growth of GDP, Dimitrios et al. (2016) found that there is a positive link between these two variables. Data employed in their study was quarterly data for the year 1990 to 2015 of fifteen Euro-area countries.

Their findings are consistent with Beck et al., (2015) who found that real growth of GDP, exchange rate, lending interest rate and share prices have significantly influence on the ratio of NPLs. In addition, Mpofu and Nikolaidou (2018) suggest that real GDP growth rate is an important macroeconomic variable that significantly influences NPLs.

Their analysis indicates an inverse relationship between GDP growth rate and ratio of non-performing loans. Other macroeconomic variables such as inflation rate, domestic credit to private sector by banks as a percentage of GDP, global volatility, and trade openness are significantly positively related to the NPLs. IMF country reports DP/2021/014 (2021) are used to pinpoint the sources of the identified NPLs episodes.

These causes could be loosely grouped into (1) adverse macro-financial shocks, (2) poorly conceived macroeconomic policies, (3) problems originating in the banking sector itself. and (4) other structural issues. Jabbouri and Naili (2019) tested the effect of bank-specific and macroeconomic determinants on NPLs across 98 banks from ten emerging countries in MENA, during 2003 and 2016. Their study revealed bank size, ratio of capital adequacy, bank-operating efficiency, profitability of the prior year, growth of GDP, inflation, unemployment, as well as public debt are the key determinants of NPLs in the region. However, growth of loans has an insignificant effect on the behaviour of non-performing loans. Likewise, Alshebmi et al., (2020) examined the relationship between the non-performing loans and selected bank and macroeconomic determinants of twelve Saudi commercial banks from 2009 to 2018. They found a negative correlation between NPLs and return on assets, growth of GDP, liquidity risk and credit risk of their sample banks. Unlike the results found by Jabbouri and Naili (2019), NPLs and capital adequacy ratio relationship is insignificant in the study performed by Alshebmi et al., (2020). In his study on emerging economies for the year 2000 to 2013, Bayar (2019) grouped the variables he employed into three categories: macroeconomic variables, institutional quality variable and bank-specific variables.

Macroeconomic variables are represented by growth of real GDP per capita, unemployment rate, inflation rate, government gross debt, net lending/borrowing, institutional variable is measured by economic freedom index, and bank-specific variables are domestic credit to private sectors to GDP, capital adequacy ratio, ROA, ROE, non-interest income to total income and cost to income ratio. Consistent with other studies, both real GDP growth and capital adequacy ratio were shown to be significant related to NPLs level.

Further, institutional quality appeared to be negatively related with NPLs which supports findings by Boudriga et al. (2010). Studies using by Kjosevski and Petkovski (2017), Us (2018) and Laryea et al., (2016), all confirmed that there is a link between macroeconomic and bank-specific variables with NPLs of their sample banks data from countries of other regions mentioned above found similar results. As for Asian region, Zhang et al., (2017) tested the impact of spatial spillover on NPLs for commercial banks in 31 Chinese provinces using data for the year 2005 to 2014. Their study revealed that the impact of spatial spillover plays an important role in shaping NPLs of banks in China. Consistent with studies using data from other regions mentioned above, the GDP growth and unemployment rate are significant factors in affecting NPLs of commercial banks in the provinces. Demirguc-Kunt and Detragiache (1997) argue that banking crises tend to erupt when the macroeconomic environment is weak, particularly when growth is low, and inflation is high.

From the above literature, we can conclude that NPLs are driven by macroeconomic and bank-specific factors regardless of where the countries’ data came from. Kalemli-Ozcan, Laeven, and Moreno, (2015), IMF (2016) noted that theoretical literature acknowledges that elevated NPLs impair bank balance sheets, depress credit growth, and delay output recovery drawing on the existing literature, this section outlines the inter-linkages between non-performing loans and economic performance.

On the one hand, macroeconomic environment and bank-specific factors affect loan performance. On the other hand, the high concentration of non-performing loans has a negative impact on the economy, slowing down the creation of new credit and worsening market expectations.

After reviewing several studies on the worldwide episodes of banking distress and banking crisis, Demirguc-Kunt and Detragiache (1997) concluded that any country whose ratio – non-performing loans to total assets in the banking system exceeding 10% could be classified as fully fledged crisis and of systemic nature. From the above literature, we can conclude that NPLs are driven by macroeconomic; bank-specific and industry factors regardless of where the sample data came from. Accordingly, this paper intends to examine the factors affecting the high NPLs in the Ghanaian banking sector from 2014-2023.

5.0. Methodology

The conceptual reviews on non-performing loan ratios and, high fiscal deficits, macro-economic factors, banks specific; and industry factors of the Ghanaian banking sector over the period 2014-2023 were conducted using a range of related literatures and additional sources from Bank of Ghana, IMF country reports such as academic research and textbooks. To do a literature review and draw a judgment (Taswan et al., 2023).

3.0 Overview of the Non-performing Loan Ratios in the Ghanaian Banking Sector over the period 2014-2023.

The recent IMF Country report 24/030 (01/2024) confirmed that the government had accumulated significant arrears in both energy and non-energy sectors in the past decade. At end December 2023, NPLs were estimated at 24.9% and several banks, including systemically important domestic banks and subsidiaries of reputable international banks, reported higher NPL ratios in the range of 20–40 percent. The stock taking exercise conducted by the authorities assessed an overall stock of arrears at end-2022 broadly consistent with initial program assumptions, with energy sector arrears amounting to some US$ 1.6 billion (2.3 percent of GDP) and non-energy sector arrears at about GHS 35 billion (5.8 percent of GDP) and all energy sector and non-energy sector arrears had all translated into the higher non-performing loan ratios over the past decade (IMF Country report 24/030 (01/2024).

The government has continued to accumulate payables over the years. Meanwhile, high fiscal deficits over the years have compounded the NPL situation, as government arrears undermined the capacity of contractors to service their obligations to banks. The inability of government to make payments to contractors and other service providers on time and this in turn, created NPLs across the banking system.

The deceleration in growth also occurred mainly in the non-cocoa/gold sectors which constituted the bulk of the banks’ loan portfolios. This has added to NPLs and also exposed weaknesses in loan underwriting standards. Ghanaian banking sector has been saddled with non-performing loans (NPLs) over the past decade, meaning that they were not able to recover loans they have provided to their customers. These had affected the ability of banks to generate income to operate their businesses. It also led to losses which eroded their capital base further. The accumulation of new arrears could compound the NPL problem and weaken banks. High fiscal deficits led to high interest rates and engendered a further deterioration in bank assets, profits, and capital. The high fiscal deficits of 15,2% in 2020; 12.2% in 2021; 9.9% in 2022 and 7.7% in 2023 posed some challenges and prospects of creating the fiscal space in the near term were uncertain as the potential for expenditure overruns were high ahead of the 2016 and 2020 elections. Ghana’s fiscal deficits and its effects on price stability and output growth have been a major source of concern to various governments in the past, Central Bank of Ghana, the private sector, civil society, domestic and international investors and other major international financial institutions like the IMF, the World Bank and Rating Agencies among others.

Fiscal deficits picked up from 6.3 percent of GDP in 2015 to 7.8 per cent of GDP in 2016. Though it declined to 5.9 percent of GDP in 2017 against a program target of 6.3 percent of GDP, it significantly ballooned again to 7.2 percent of GDP in 2018 against a revised program target of 4.4 percent of GDP in consultation with the International Monetary Fund. Inability to reduce or contain fiscal deficits have compounded the legacy debt to non-energy and energy sectors that had negatively impacted on the non-performing loan ratios. Efforts to strengthen fiscal management have been slow new arrears are reported to have emerged. In the post DDEP 2023, the banking system was liquid, less profitable and under- capitalized, non-performing loans (NPLs) were very high and a significant segment of the banking industry was fragile.

The solvency of most banks was threatened by poor asset quality, which had led to significant impairments of capital. Credit growth has declined over the period while asset quality had been a source of concern. Results of an Asset Quality Review (AQR) of the banking industry review over that past decades showed that, some banks had impaired capital leading to capital erosion below the required regulatory levels.

Consequently, such banks lacked sufficient capital to support the risks inherent in their asset base, and had no capital buffers to withstand further losses that could arise from external shocks. Data review on the non-performing loans in the banking sector from 2014 – 2023 indicated the rising trend over the period.

Also, global data gleaned from 72 countries including some Africa countries in December 2022 on the non-performing loans, Ghana stood at 4th (15% in 2022) (24.6% in 2023) just behind Equatorial Guinea (55.1%) and Chad (27.1%) respectively while lagging behind La Cote d’Ivoire recording 8.8% and Nigeria 4.01% respectively.

According to Demirguc-Kunt and Detragiache (1997) posited that any country whose NPLs exceeds 10%, that country’s banking sector is in crisis. The average non-performing loans in the banking sector from 2014 – 2023 is 16.97%, with the lowest figure of 11% in 2014 and the highest figure of 24.9% in 2023. This is an indication of the sector being in a fully- fledged crisis as a results of general repayment challenges on the part of borrowers reflecting general weak macro-economic imbalances in the form higher inflation, higher policy rates associated with higher lending rates, persistent depreciation of the local currency against the major trading currencies, higher energy cost and harsh business environment. Also, the non-performing loans (NPLs) ratio increased from 15.0 percent in December 2022 to 24.6 percent in December 2023, on the back of the 2022 economic downturn, with the rising inflation rate, depreciation of the local currency against major trading currencies’ and at the back of domestic debt restructuring.

The large share of loans classified as ‘loss’ in systemwide NPLs points to banks’ inability to effectively recover distressed loans—partly due to weaknesses in the legislative and institutional framework for insolvency and creditor rights—and suggests that further write-offs may be needed to help clean banks’ balance sheet. In the course of the year 2023, the pace of growth in private sector slowed down to 10.7% compared to 31.8% annual growth in December 2022.

In real terms, credit in the private sector contracted by 10.2% relative to 4.5% contraction recorded over the comparable period. Credit to the private sector as a share of GDP is relatively low in Ghana compared to peer countries and has been declining over the past decade; and the lack of access to finance is often cited by the private sector as a key constraint to investment, particularly for small and medium-sized enterprises (IMF Country Report No. 24/30)

. The increase in public debt was found to have led to higher NPLs. This could be because higher public debt increases the sovereign risk premium, affecting banks’ funding costs and lending rates. High debt also increased the probability of government arrears accumulation, which was translated into higher NPLs in 2023. Another explanation was that the crowding-out effect (which raises borrowing costs for the private sector and increased the likelihood of borrower’s default) has been stronger over the more recent period.

Many banks were saddled with non-performing loans (NPLs), meaning that they were not able to recover loans they had provided to their customers. This affected the ability of banks to generate income to operate their businesses. It also led to losses which eroded their capital base further. The solvency of most banks has been threatened by poor asset quality, leading to significant impairments of capital. According to Bank of Ghana’s report the banking industry’s asset quality improved during the period under review following the decline in the NPL ratio from 15.2 percent in December 2021 to 15.0 percent in December 2022. Ghana’s economy showed signs of weaknesses with the various international credit rating agencies downgraded the economy that led to slowdown of GDP growth, declined in confidence among businesses and consumers.

The higher inflation, higher policy rate with the associated higher lending rates and persistent depreciation of the local currency against the major trading currencies impacted negatively on non-performing loans. Over the course of 2022, the Ghana Cedi depreciated against all the major trading currencies like US$, Euro and Great British pound sterling. While the Ghana Cedi was exchanged for GHC6.02 at the beginning of the year it ended at GHC 8.6 to US$I that represented 42.8% depreciation. The industry’s NPL stock, increased from GH¢8.2 billion in December 2021 to GH¢10.4 billion in December 2022, partly reflecting the revaluation of foreign currency NPLs and the deterioration in some domestic currency loan portfolios (BoG Monetary Policy Report, BOG Research Department – January 2023).

According to Bank of Ghana’s banking sector development report (2020) reported that the quality of assets within the banking sector marginally declined during the year due to the pandemic-induced loan repayment challenges and slowdown in credit growth in 2020. The NPL ratio accordingly inched up from 14.7 percent in December 2019 to 15.7 percent in December 2020, after which it improved to 14.7 percent at year-end 2019 on account of improved credit growth and loan write-offs during the last quarter. The stock of NPLs increased by 9.8 percent year-on-year to GH¢7.1 billion at end-December 2020, compared with a contraction of 3.0 percent in December 2019. Banks also provided support and reliefs in the form of loan restructuring and loan repayment moratorium to cushion customers severely impacted by the pandemic, which in turn moderated the likely severe adverse impact the pandemic would have had on banks’ asset quality.

The COVID-19 economic and health crisis might have triggered a new wave of NPL increases. Economic restrictions and other disruptions (including lock-downs, curfews, and physical distancing measures) that were put in place to stem the spread of the virus have led to lower demand, higher costs of doing business, and income losses, which have resulted in some firms and households defaulting on loan repayments.in Total outstanding loans restructured by banks as at December 2020 amounted to GH¢4.5 billion, about 9.4 percent of the industry loan book. Regulatory guidance and monitoring procedures have been put in place to assess developments in this regard. According to Bank of Ghana’s banking sector development report in December 2019 reported that the banking sector non-performing loan ratio improved from 18.2% in December 2018 to 14.7% in December 2019, the decline in the ratio was due to the combination of loan recoveries as well as further write- off. The industry’s asset quality improved significantly during the period under review. The stock of the industry’s Non-Performing Loans (NPLs) declined further by 5.2 percent to GH¢6.30 billion in December 2019, following a contraction of 18.9 percent a year earlier. The positive effect of the decline in the stock of NPLs on the NPL ratio was influenced by a strong pick up in gross credit within the review period, with a resultant decline in the NPL ratio to 14.7 percent in December 2019 from 18.2 percent in December 2018. The industry’s NPL ratio adjusted for the fully provisioned loss loan category also declined to 6.7 percent in December 2019 from 10.2 percent in December 2018. Continued implementation of the ongoing loan write-off policy, intensified loan recoveries, and enhanced risk management practices, could support further reduction in the industry’s stock of NPLs. In Ghana, the system’s NPL ratio fell from above 20 percent in mid-2018 to 14.7 percent at the end of 2019, with additional write-offs accounting for about 3 percentage points according to the Bank of Ghana (2018).

From the Bank of Ghana’s banking sector development report (2016) showed that the non-performing loan for the banking industry also increased from 14.7% in December 2015 to 17.3% in December 2016. The indicators of asset quality at the end of December 2016 pointed to deterioration in the loan book of banks relative to the same period last year. The stock of NPLs increased from GH¢ 4.4 billion in December 2015 to GH¢ 6.2 billion in December 2016. The deterioration was partly explained by the slowdown in growth of loans and advances, as growth in the stock of non–performing loans (NPLs) declined sharply from 64.6 percent in December 2015 to 39.1 percent by end 2016. Adjusting for the fully provisioned loan loss category, the NPL ratio stood at 8.4 percent in December 2016, compared with 6.8 percent at the end-December 2015.

The high non-performing loans in the banking sector was largely due to the general slowdown in the economy, and high cost of production especially from high utility tariffs. With the onset of payments to reduce energy sector related SOE debts, the proportion of banks’ NPLs attributable to the public sector declined from 3.9 percent in December 2015 to 3.2 percent in December 2016. The private sector, however, contributed 96.8 percent of the total banking sector’s non-performing loans as at December 2016, up from 96.1 percent in December 2015, while accounting for 85.1 percent of total credit in December 2016 compared with 87.3 percent of credit received in 2015. The level of NPLs associated with the private enterprises was driven mainly by indigenous enterprises, which received 61.1 percent of credit to private enterprises but accounted for 78.9 percent of NPLs as at December 2016. Households’ share of private sector credit declined from 14.8 percent to 13.4 percent while its contribution to NPLs declined from 6.8 percent to 4.4 percent over the review period (Bank of Ghana Banking Sector Summary January 2017). According to Bank of Ghana’s banking sector development report revealed that the non-performing loan ratio increased from 17.3% in December 2016 to 22.7 in December, 2017.

Banks’ stock of non-performing loans increased from GH¢6.14 billion as at end-December 2016 (39.0% year-on-year growth) to GH¢8.58 billion in December 2017 (39.8% year-on-year growth). In addition to the marginal pickup in the year-on-year growth in the stock of NPLs, the increased NPL ratio was attributable to a slowdown in industry loans (from 17.6% in December 2016 to 6.4% in December 2017). Adjusting the industry’s NPLs for the fully provisioned loan loss category, the ratio stood at 10.8 percent in December 2017 compared with 8.4 percent in December 2016. The public sector’s contribution to the industry’s NPLs increased from 3.2 percent in December 2016 to 5.7 percent in December 2017. The private sector, the larger recipient of industry loans, contributed the remaining 94.3 percent of the industry’s NPLs in December 2017, indicating a decline from the 96.8 percent in December 2016. Indigenous private enterprises accounted for 80.6 percent of total NPLs in December 2017 compared with a share of 78.9 percent in 2016, while the contribution of foreign enterprises declined to 7.9 percent from 13.2 percent. Households accounted for 5.2 percent of total NPLs in December 2017, compared with a share of 4.4 percent in December 2016 (Bank of Ghana Banking Sector Report/January 2018).

According to Bank of Ghana’s December 2015 annual report noted that the non-performing loans (NPL) ratios of banking sector deteriorated in 2015. The NPL ratio (including the loss category) increased to 14.7 per cent at end 2015 from 11.0 per in 2014, mainly on account of the general slowdown in economic activity and challenges posed by the worsening energy crisis. Adjusting for the fully provisioned loan loss, the NPL ratio stood at 6.8 per cent in 2015, compared with 5.3 per cent in 2014.

The pace of domestic economic activity marginally slowed down in 2015 relative to 2014, largely due to the effect of the energy sector challenges especially on industry. According to the GSS, real GDP grew by 3.9 per cent compared with 4.0 the year due to pass-through effects of a series of upward adjustments in utility tariffs and petroleum prices, as well as depreciation of the domestic currency. Consequently, headline from 17.0 per cent in the preceding year. For both the years 2014 and 2015 upward adjustment of utility tariffs, depreciation of the domestic currency as well as inflation impacted negatively on the banking sector’ non-performing loans. High fiscal deficits led to high interest rates and engendered a further deterioration in bank assets, profits, and capital. The high fiscal deficit of 15,2% in 2020; 12.2% in 2021; 9.3% in 2022 and 7.7% in 2023 posed some challenges and prospects of creating the fiscal space in the near term are uncertain as the potential for expenditure overruns were high ahead of the 2016 and 2020 elections. Inability to reduce or contain fiscal deficits have compounded the legacy debt to non-energy and energy sectors that had negatively impacted on the non-performing loan ratios.

Ghana’s fiscal deficits and its effects on price stability and output growth have been a major source of concern to various governments in the past, Central Bank of Ghana, the private sector, civil society, domestic and international investors and other major international financial institutions like the IMF, the World Bank and Rating Agencies among others. Fiscal deficits picked up from 6.3 percent of GDP in 2015 to 7.8 per cent of GDP in 2016. Though it declined to 5.9 percent of GDP in 2017 against a program target of 6.3 percent of GDP, it significantly ballooned again to 7.2 percent of GDP in 2018 against a revised program target of 4.4 percent of GDP in consultation with the International Monetary Fund. Various governments in the past including the current government had to deal with the negative the plaque of fiscal deficits financing and its negative consequences on other macroeconomic variables particularly on inflation in the Ghanaian economy (Osei, and Olawale Oguloka, (2022).

According to Demirguc-Kunt and Detriagache (1998) the Ghanaian banking sector has been classified as fully-fledged banking crisis and of a systemic nature as a result of average NPL ratios of 16.97% as against the acceptable NPLs ratio of 10%. The high NPL ratios had been due to high fiscal deficits, macro-economic instabilities of high inflation, persistent depreciation of the local currency, higher policy and interest rates were found to have affected banks’ asset quality. the macroeconomic environment deteriorated rapidly, reflecting a confluence of a food and energy crisis and an expansionary fiscal policy.

As fiscal deficits widened, inflation accelerated, interest rates rose to above 30%, investors became skittish and began to exit the debt market, and the exchange rate began to depreciate, thereby creating conditions for asset price deterioration. In this regard, exchange rate depreciation had a negative impact on asset quality, particularly in foreign owned banks with a large amount of lending in foreign currency to un-hedged borrowers, and interest rate hikes affect the ability to service the debt. Economic downturn in 2022/2023 with its higher inflation, local currency depreciation has all exerted significant pressures on borrowers, thus making them increasingly challenging for them to pay off their loan obligations. The rate of inflation remained high and volatile during much of the period (US$1-GHC3.025) 2014- US$1-GHC 12.15) 2023. The rate of depreciation of the local currency, the cedi, depreciation in the 2016-2023 period and the budget deficit situation has persisted all impacted on non-performing loans. These unstable macro-economic conditions impacted negatively on the non-performing loans, mobilization of deposits and the financial depth of the economy.

The result showed that stability risks had heightened considerably, with high nonperforming loans (NPLs) and undercapitalized banks. Macroeconomic instabilities impacted negatively on Ghanaian banks’ capital over the period under review. The new capital requirement was necessary to align banks’ capital base more closely with macroeconomic realities. High inflation and rapid currency depreciation over the years (cumulative depreciation of the cedi by 51.8 per cent between end-December 2013 and end-April 2018) meant that in dollar terms, the 2007 and 2013 minimum capital requirements of GH¢60 million (US$ 61.8 million at end-December 2007) and GH¢120 million (US$56.4 million at the time) had depreciated in value to $13.6 million and $27.2 million respectively, as at end-April 2018. The financial sector cleanup in 2017-2019 did not yield the intended effects, primarily because of the lack of sustained improvements in the macroeconomic environment.

The need to improve macroeconomic stabilization measures, especially fiscal stabilization, is quite clear. However, weaknesses in the fundamental structure of the economy impacted negatively on the banking sector. High budget deficits led to increasing interest rates on government debt reorienting credit away from the private sector to the government which has led to crowding out. The underlying real economy also showed structural weaknesses which made it vulnerable to instability, and poor agricultural sector and trade performance. The government’s dominance in economic activity, against the backdrop of weaknesses in fiscal management, has further increased vulnerabilities in the banking sector. State-owned enterprises (SOEs) and many small-and medium enterprises (SMEs) rely heavily on business from the government. Consequently, the government’s accumulation of payment arrears to contractors and other service providers has undermined their capacity to service their bank loans and created NPLs across the industry.

The 2022 economic downturn has impacted negatively on the level of NPLs as increased as unemployment rose and while small medium enterprise and individual borrowers faced greater difficulties to repay their debt to the banks. Weaknesses in enforcing prudential regulations allowed banks to build up substantial loan concentrations while deficiencies in the analysis of individual bank risk and systemic risks have led to an under-appreciation of the stability risk implications. High and rising NPL ratios had severely limited the ability of the banking sector to provide new credit and support the Ghanaian economy. The negative effect of NPLs on credit to the private sector has been observed at both banking system and individual institution levels, with banks that hold large NPL portfolios providing on average fewer loans.

From the global data Ghana has one of the highest and most volatile NPL ratios in the world. Finally, some of the banks that have high NPLs tended to display performance indicators denoting lower profitability and capital, and higher funding costs and provisions. On the one hand, a larger portfolio of NPLs have resulted into lower interest income, higher provisions, and higher funding costs, which have impact negatively on banks’ profitability and capital. On the other hand, lower-performing banks are more exposed to moral hazard issues because managers face incentives to pursue risky loans in the hope of extra profits from additional credit risk, which may translate into higher NPLs. After reviewing several studies on worldwide episodes of banking distress and banking crisis, Demirguc-Kunt and Detragiache (1998) concluded that for an episode of banking distress to be classified as ‘a full-fledged crisis… and of a systemic nature’, at least one of the following four conditions had to hold: (i) the ratio of non-performing assets to total assets in the banking system exceeded 10%.(ii) The cost of the rescue operation was at least 2% of GDP. (iii) Banking sector problems resulted in large-scale nationalization of banks. (iv) Extensive bank runs took place or emergency measures such as deposit freezes, prolonged bank holidays, or generalized deposit guarantees were enacted by the government in response to the crisis. From the data and literature review by Demirguc-Kunt and Detriagache (1998) on the Ghanaian banking sector with average of 16.97% over the period under review the banking sector could be classified as fully-fledged banking crisis and of a systemic nature. The factors that have driven the non-performing loan in the Ghanaian banking sector for the period under review were four broad groups: macroeconomic conditions (such as high inflation, higher interest rate, persistent depreciation of the Ghanaian currency and real GDP growth); bank-specific factors include (poor underwriting skills, weak credit risk management. poor internal controls, connected lending, insider dealings and frauds are often the source of poor asset quality, and industry factors (legal, protracted courts issues on loan default matters, regulatory matters and other judicial issues) and high fiscal deficits.

The potential for expenditure overruns was high ahead of elections in 2020, and fiscal slippages that led to an accumulation of new arrears negatively impacted the banking sector. Ghana’s fiscal and external positions deteriorated significantly in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, the tightening in global financial conditions and the war in Ukraine. These external shocks, combined with pre-existing fiscal and debt vulnerabilities, have pushed public and external debt up. Ghana lost international market access in late 2021, and the macroeconomic situation became more challenging in 2022, with large losses in international reserves, sharp depreciation of the exchange rate and soaring inflation, an increase in Eurobond spreads to distressed levels, and extremely constrained domestic financing conditions. These issues have all impacted negatively on the non-performing loans ratios for the period 2021 – 2023. As fiscal deficits have widened over the years, while inflation accelerated to 54.1% in 2022, interest rates rose to around 30 percent, investors became skittish and began to exit the debt market, and the exchange rate began to depreciate, thereby creating conditions for asset price deterioration or default. However, NPLs are very high across the industry and pockets of fragility remain. At end December 2023, NPLs were estimated at 24.9% and several banks, including systemically important domestic banks and subsidiaries of reputable international banks, reported higher NPL ratios in the range of 20–40 percent.

From the literature review on the causes of the rising non- performing loans in the banking sector have been due to economic downturn, banking sector related issues, borrowers’ related issues and legal, regulatory, judicial problems and high fiscal deficits had prevailed over the years in the banking sector. The country has experienced economic downturn in terms of higher interest rates, higher inflation, persistent depreciation of local currency, inability of the government to pay contractors and service providers on time have exerted significant negative impact on businesses and other borrowers to repay their loan obligations. A comprehensive grasp of these economic forces could be pivotal in managing and reducing the country’s higher non-performing loans ratio. The other factors behind the high non-performing loans in the banking sector were inappropriate credit risk management, irresponsible borrowing, poor supervision, and weak governance. Banks and other lenders’ related issues have contributed not in small ways in the higher non-performing asset ratio in the banking sector.

Financial institutions including banks were not immune to the NPLs related issues which included the presence of poor credit underwriting, weak credit reference procedures, inadequate and poor credit risk management including monitoring and recoveries procedures and processes have all resulted in the up-ticked in the recent NPLs data. Bank lending and moral hazard. Banks with higher average interest rates on loans (measured as the ratio of interest income to gross loans) have higher NPL ratios, probably because of customers’ difficulty in repaying more expensive loans and adverse selection effects. In addition, highly leveraged banks, as captured by the loan-to-deposit ratio, have higher NPL ratios, perhaps because they tend to take more risks. Poor borrower assessments including frauds and weaknesses in loan underwriting standards have all affected the up ticked of non -performing loan in the banking sector over the period under review. Lack of integrity and honesty on the part on borrowers have all played pivotal role in the emergence of non-performing loans in the banking sector. Issues such as bankruptcy and insolvency defaults in payment and fraudulent activities have contributed to the higher non-performing loans in the banking sector. Borrowers felt rather powerless in dealing with banks and non-bank financial institutions, high interest rates, hidden charges, non-disclosure of persistent information, and unfair denial of access to credit at reasonable interest rates.

Aggressive lending and high exposures to risky sectors like government of Ghana (GoG) road contracts for example, National Investment Bank involved in the government of Ghana contracts. Weaknesses in the legal, regulatory and judicial systems have all contributed to the uptick in non-performing loans in the banking sector over past decade. Protracted legal disputes, persistent adjournment in credit related by courts and weaknesses in the Borrowers and Lenders Act 2020 (Act 1052). Protracted legal disputes on credit issues, difficulty in enforcing and executing collaterals through the court systems and compliance complexities have negatively impacted on the non-performing loans in the banking sector. However, the Borrowers and Lenders Act 2020 Act 1052 has provided the legal framework for credit, improved the standard of disclosure of information for both lenders and borrowers but not included the legal rights for the lenders to dispose collateral used to support bank facilities without resorting to the courts.

The establishment of the Collateral Registry at the Bank of Ghana, as mandated under the Borrowers and Lenders Act 2020 (Act 1052) was indeed a welcomed innovation to credit delivery in Ghana.The enactment of Act 1052 and the Collateral Registry Application Software (CRAS) has further enhanced the following services rendered by the Registry to its clients:

-

the platform for registration of security interest in both movable and immovable assets

-

the platform for conducting searches on assets pledged as collateral.

-

assisting with the realization of security interest, upon a default, without court order

-

the platform for registering other post- registration activities, (i.e. discharges, amendments, transfer of registration, subordination of registration, appointment of receiver or manager and notices of default)