In his 2023 Mid-Year Review (MYR) Statement to Parliament, the Minister for Finance (Hon. Ken Ofori-Atta) made the following significant departure to date from Ghana’s prudent public financial reforms and best practice in Paragraphs 72 and 73—

“Mr. Speaker, before discussing the 2022 fiscal outturns, we would like to note that the fiscal anchor, in the context of IMF-supported PC-PEG, is the Primary Balance on commitment basis. To align with this requirement, the Government, therefore, had indicated in paragraph 210 of the 2023 Budget Statement, that the fiscal accounts would, henceforth, be reported on commitment basis, thereby, taking into account outstanding unpaid commitments of Government”.

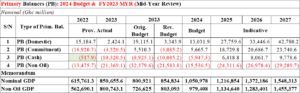

Consequently, the MYR Statement and 2024 Budget presented to Parliament appear to place significant emphasis on the Primary balances (PBS)—as shown in various Memoranda Items, Table 3A [Summary of Central Government Operations]. The recent FY2024 Budget continues to show the PBs and Fiscal Balances (FBs), as summarized in Tables 1A and 1B below.

Table 1A: Summary of Primary Balances (Nominal)

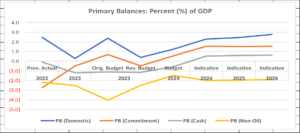

Table 1B: Summary of Primary Balances: Percent [%] of GDP

Source: 2023 MYR & 2024 Budget Statement

The Percentage (%) to GDP in Table 1B is shown in Graph Figure 1 below, as a visual expression of the trends underlying these balances or budget performance.

Figure 1: Primary Balance Medium-Term Estimates

As discussed later, the main differences between the Primary and Fiscal Balances are interest payment, arrears (routine and exceptional), and debt repayment or amortization. Primary Balance is Total Revenue less Total Non-Interest Expenditure. Since the Fiscal Balance is Total Expenditure, another definition is that the Primary Balance is the Fiscal Balance less Interest payments.

- Ghana needs a more ambitious fiscal target

From a policy and legal perspective, Ghana should set more ambitious fiscal targets than the IMF Program requires. These include (a) Overall Fiscal Balances (commitment and cash bases) targets; and (b) shift to semi-accrual accounting to account for arrears and other liabilities; and (c) a debt repayment or amortization methods (e.g., establishment of a Sinking Fund in FY 2014 to liquidate about US$550 million of the first 2007 Sovereign Bond of US$750 million.

These are necessary since it is very fiscally challenged, with huge arrears, and has defaulted in meeting debt commitments. Hence, the Primary Balance shows an optimistic (positive) path to meeting its commitments under the IMF Program it is implementing. Secondly, Ghana is now a Lower Middle-Income Country (L-MIC) and must begin to incorporate more sophisticated criteria into its fiscal management—also as a way to minimize its current fiscal risks.

While the Article admits that the Primary Balance (PB) is an accepted fiscal performance target, it is a softer fiscal performance target compared to the Overall Fiscal Balances (FB). The reason is that the PBs are based on actual cash flows in Low-Income Countries (LICs) and, as with countries in transition like Ghana, many Lower Middle-Income Country (MIC) status.

- Importance of Arrears in the Fiscal Balances

For Ghana, the use of the primary balances remarkably undermines the more prudent shift to semi-accrual rules under earlier fiscal and public financial management (PFM) reforms. The article acknowledges that Ghana’s budgets and past IMF Programs have cited the “primary balance” (commitment basis) as “fiscal anchor”.

Tables 2A and 2B, which compare the Primary and Fiscal Balances, show that Ghana could meet the PB criteria (green shade) but not the fiscal balances (red items). More important, it seems to be repeating the complacency from 2017 to 2019, when it showed superior fiscal performance through very low arrears (“offsets”) that relegate the exceptional balances to “appendix” or “memo” items in Budgets.

Table 2(A): Nominal Fiscal and Primary Balances (Ghc million)

Table 2(B) shows Table 2(B) in percentage of GDP and the significant differences between the PBs and FBs. For example, after adding arrears, the positive primary balance of 2.5 percent in FY2022 increased to a 7.2 percent fiscal balance (cash). The effect of arrears on fiscal performance is to sink the fiscal gap deeper into negative territory.

Table 2(B): Fiscal and Primary Balances: Percent (%) of GDP

Figure 2(B) shows the differences among the fiscal and primary balances. It is noted that the fiscal consolidation, as designed in the Budget and under the IMF Program, will occur in the outer years of the Program.

Figure 2B: Graphical Presentation of Fiscal and Primary Balances

The Tables and Graphs show that the difference between the Fiscal Balances (commitment and cash basis) is accumulation of arrears (accounts payables). Hence, Ghana created a Contract Database as a link to the Accounts Payable module in GIFMIS to track the value of supplies and contracts awarded as well as creditors to minimize the risk to fiscal management. A detailed discussion of the current arrears situation continues in Section 5 below.

- Impact of Debt Repayment (Amortization)

The increase or decrease (rate of accumulation) of Public Debt depends on the amount put aside for amortization (i.e., provision and actual repayment of existing and current debt). Table 3A shows the provision for amortization, in addition to payables, in recent fiscal statements.

Table 3A: Impact of Arrears (including Bailout Costs and Offsets)

Table 3B shows Table 3A in cumulative format, to stress that Arrears increase the budget deficit to be financed while amortization reduces the amount to measure the rate of debt accumulation.

Table 3B: Cumulative Impact of Arrears & Amortization

Table 3C and Figure 3A show Tables A and B in percent (%) of GDP and in itemized and cumulative formats—the real measure of showing the fiscal performances.

Table 3C: Cumulative Accrual & Repayment Items

Figure 3A: Itemized and Cumulative Graphs of Accrual and Repayment Amounts

From an IMF Program viewpoint, Fig. 3 (cumulative) shows that the expected fiscal contraction and heavy lifting, from both primary and fiscal balance perspectives, will go beyond FY2024. In this regard, the proper use of the Sinking Fund to achieve a decline in rate debt accumulation is relevant. The Fund was NOT designed as substitute for the normal or current amortization provision in the budget—as seem to be the current practice.

Were this to be adequate and appropriate policy, the nation would NOT have defaulted. Hence, the intuitive purpose of the Sinking Fund is to increase the total debt repayment amount above any new or annual borrowing (i.e., Fiscal Balance on Cash Basis). Note that, in principle, this is also equal to the annual amount of “Financing” in the last component of the Fiscal tables.

- Problem of Pipeline Contracts and Arrears

The bane of Ghana’s fiscal data management and reporting is an accounting base that relies on cash receipts and payments instead of liabilities or arrears. It does not properly account for the significant “pipeline” of contracts and unpaid bills that cause Budget overruns. Given its deficiencies, the last government decided to move the country to “semi-accrual” accounting basis of fiscal management.

The unusual size of the “pipeline” of contracts (MDAs/MMDAs) and “arrears” (MOF, CAGD & BOG) has been highlighted since FY2017 even though the Contract Database was completed in FY2016. It worsened the reliance on “offsets”, “footnotes” and “memo” that make the fiscal balances and debt impressive. Between 2017 and 2020, no Public Expenditure Review Reports were published [or made public], as required by the Public Financial Management Act, 2016 (Act 921). Hence the publication of the 2021 and 2022 Reports has been quite revealing.

Tables 4 and 5 show the arrears data in percentages (%) of Total Amounts (Nominal amount & in Gross Domestic Product [GDP]).

Table 4: Details of Contracts & Arrears—Nominal (Ghc million)

Table 5: Details of Contracts & Arrears—Percent (%) of GDP

The Annual Budget Performance Reports (FY2021 & FY2022), IMF ECF Program and IMF Debt Sustainability Analysis (DSA) also reveal a steep decline in arrears of about Ghac37 billion (equivalent to the 2022 Budget deficit). The difference was added to the “Domestic Debt” component of the Public Debt [see IMF DSA]—likely, the result of negotiations with the affected contractors and suppliers. Further, the “offsets” made to the FY 2016 arrears in the FY2017 Budget have been repeated in the FY2023 Budget under the FY2022.

- Ghana’s PFM laws have a higher standard (including Primary Balance)

Ghana’s Public Financial Management Act (PFMA) 2016 (Act 961) and PFM Regulations (PFMR), 2019 (LI 2378) are relevant to the discussion; The PFMR is explicit that Ghana should prepare its Public Accounts and, therefore, Budget on “semi-accrual accounting” rules.

Basis of accounting (Regulation 208): The accounting basis of a covered entity for the recording of revenue, expenditure, assets and liabilities shall be on an accrual basis of accounting or as determined by the Controller and Accountant-General”.

Further, the primary balance is among six (6) fiscal indicators that are “anchored” firmly in the PFMA [s16]. The PFMA (Act 961) states the following as Fiscal Policy Indicators (s16{a})

- Compliance by government with the fiscal policy objectives, fiscal policy principles and other requirements shall be assessed in accordance with the following indicators (s16{1})

- the non-oil primary balance (PM) or non-oil fiscal balance (FB), as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP); and

- Any two (2) of the following fiscal policy indicators

- Public debt as a percentage of gross domestic product;

- Capital spending as a percentage of total expenditure;

- Revenue as a percentage of GDP; or

- Wage bill as a percentage of tax revenue.

- The Minister shall review the fiscal policy indicators specified in subsection (1) every five (5) years.

However, the Fiscal Responsibility Act (FRA), 2018 (Act 982), based on PFMA s13-17, quantifies only one (1) of these indicators—the Overall Fiscal Balance (NOT the Primary Balance). Section 2 (Fiscal Responsibility Rules) of the FRA 2018 (Act 982) states–a

“Despite the fiscal policy indicators stated in Section 16 of the PFMA Act, 2016 (Act 921), the following numerical fiscal responsibility rules shall apply in tin the management the public finances:

- the overall fiscal balance on cash basis for a particular year shall not exceed a deficit of five (5) percent of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) for that year;

- an annual positive primary balance (PB) shall be maintained.

It is obvious that the laws are very clear and specific with respect to the fiscal indicators and their prioritization. Hence, the Article argues that the Minister may only change the conditions set in the law without recourse to a formal Parliamentary process.

- Immediate past reform efforts

Ghana is emerging as an “L-MIC economy without effective and prudent fiscal management practices that include (a) budget overruns caused by weak controls over commitments or arrears that lead to (b) huge deficits, borrowing and public debt that are difficult to control. Hence, the Ghana Integrated Financial Management Information System (GIFMIS) initiative was to improve fiscal accounting based on semi-accrual” accounting rules.

GIFMIS is an element of the nation’s Public Financial Management (PFM) reforms that focusses on better systems and processes for efficient revenue or tax mobilization and prudent expenditure management, borrowing and debt management. Some specific reform steps include—

- Contract database: an electronic database that compiled the value of contracts awarded, work-in-progress (WIP), certified amounts, payments, and outstanding liabilities.

- Semi-accrual accounting: the contract database was to link to an accounts payable module in GIFMIS to improve the management of arrears. The FY2015 Budget noted that the Public Accounts were to be presented in semi-accrual format by the Controller and Accountant-General.

- Budget buffers: this is based on the Stabilization Fund as a counter-cyclical initiative under the country’s Sovereign Wealth Fund (SWF) policy—Section 9 of the Petroleum Revenue Management Act, 2011 (Act 815).

- Sinking Fund: this debt repayment reserve fund was established in 2014 with flows from the Stabilization Fund to smoothen the accumulation of debt due to rollovers and risks from the difficulty in deferring and paying “bullet” loans—see 1992 Constitution, Article 182(2) and PFMA (Sections 37 to 44).

- Contingency Fund: this was Ghana’s original crisis or stabilization Fund under the 1992 Constitution, Article 177 (Chapter 13 Finance) but it was established in 2014 and has since been a conduit for funneling the petroleum funds for consumption.

The reliance on the Central Bank to finance the large deficits has depleted the country’s foreign exchange reserves and monetization that has led to high levels of inflation and slow growth. Yet the country has defaulted in meeting its loan commitments and has been forced into an IMF Program again.

- Conclusion

If the challenge facing the nation is raising more revenues and reducing expenditures—and, consequently, the budget deficit or fiscal balances, then the focus must be on the fiscal balances. As the ensuing Tables and Graphs above show—and consistent with the IMF Program—Ghana must enhance past initiatives such as contract/arrears database and the automated system (GIFMIS) that seek to improve expenditure management.

Clearly, the IMF Program and reform goals aim to improve the Overall Fiscal Balance and not the narrower Primary Balance. However, the Program appears to be silent on bringing back Ghana’s past debt repayment and budget buffer plans. For the purpose, these policy initiatives channeled petroleum revenues into the Sinking and Stabilization Funds.