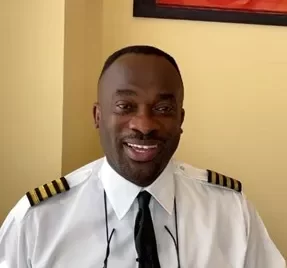

Captain Victor Kwesi Amoah outlines another episode of aviation history in the following interaction in chat with the B&FT

Judging by your headlines do you mean to say there was no commercial activity prior to World War l?

Yes, there was no commercial activity. What happened was that as we can see from the previous features, there was a pre-17th December, 1903 era where flying was more of air balloons, gliders, and others that relied on free air to stay afloat. Some records were set and some awards given. Then the Wright Brothers came in in 1903 to launch their self-motorised device. Prior to World War l, nobody was thinking about flying passengers and freight. The world then was so busy trying to outcompete to see whose invented aircraft was better in terms of speed, height and distance.

Even though that era had exchange of money, it did not mean it was a commercial venture because nobody had thought of airports and its allied business services. It was just an era of flight enthusiast and adrenaline junkies doing what they did best.

There was open ground accessible to people to test their aircraft, and that was what led to the development of the airport we see today. That open field was for air racing purposes since it was through the racing of the competitors that determined whose device was truly outcompeting.

Spectators gathered at those open fields to cheer and/or to boo depending on which side they supported; and there were food and beverage vendors selling to the crowd. It was always an event that also came with its euphoria as flight records were set and broken, sometimes unsuccessfully leading to crash landings and the catastrophes that came with it.

Those grounds, as of then, were called Aero Dromos (Greek for Air racing) /Aero Dromus (Latin for air racing).

Flying was done in remote areas and people went to enjoy the racing. There was no commercial activities then as we see today in the form of passenger, cargo service and military hardware being flown from place to place for money.

How then did they survive to sustain invention and dare-devilling events?

When the aero dare-devils’ activities were going on in all that decade, there was no service rendered in exchange for cash. The question is, how did all such events succeed since there was no exchange for money.

Most of the aero dare-devils themselves were very rich, so they funded their own activities. Those who were not rich gave themselves targets, saved money in their private businesses and ventured into manufacturing of aircraft or gaining tuition from the Wright brothers on how to fly. Some of them – who had received basic flying from the Wright Brothers – used other people’s aircraft for competition.

Interesting to note, not all aero dare-devils were engineers, pilots and designers. Some businessmen too supported the aero dare-devils. One of such businessmen who sponsored the development of aviation even in the pre-17th December, 1903 was Henri Deutsch Dela Meurthe – born in September 1846 and died in 24th November, 1919. He was a petroleum businessman called Oil king of Europe. He was a supporter of early aviation.

Two of his prizes is what is known in aviation as First prize. It was sponsored prior to 17th December, 1903 – in April 1900. He offered the prize called Deutsch Dela Meurthe for any of the first machines then capable of flying a round trip from Saint Cloud to the Eiffel Tower in Paris in less than 30 minutes.

The contestant to win that competition needed an average speed of 22kmp/h (14 miles) and cover that round distance trip of 11km (6.8 miles) in an allotted time of 30 minutes.

The contestant who won that price was Alberto Santos-Dumont, who clocked 29 minutes and 30 seconds.

The second prize was sponsored by a British Daily Mail that put the spotlight on Louis Bleirot on 25th July, 1909. He crossed the English Channel from France to England, winning the prize of £1,000. (US$4,850).

Deutsch Dela Meurthe introduced a new prize sponsorship to develop aviation. In 1904, he, in collaboration with Ernest Arch-deacon, created the Grand Prix D’aviation (Deustch Arch-deacon prize). It was a prize of 50,000 francs for the first person to fly a circular 1km course. That competition was won by Henri Farman on 13th January, 1908 at Issy-les-moulineaux in a time of 1 minute, 28 seconds.

He also put another prize called Coupe Deustch Dela Meurthet. That air speed race was held intermittently from 1912 to 1936, with 20,000 francs offered first by Deustch, and later by the Aero Club of France, and thirdly by his daughter Suzzane De la Meurthe.

William Randolph Hearst offered the Hearst Prize for anyone who could fly from the eastern side of America to the western side (Coast to Coast in whichever direction in less than 30 days). The person who won that prize was Calbraith Rodgers.

A company called Armour & Co. that was into grape soft drink production sponsored Rodger to do the trip. They provided a cargo train that trailed the flight along the route. That train had an aircraft maintenance technician to cater for repairs as and when needed, movable grocery, spare parts shop, and all that was essentially needed for the trip.

Those were some of the many people who grew the aviation industry through sponsorship events or offering prizes. We doff our hats to them for the risks they took to spur this industry on to what we admire today. Ayekoooo!!!

How did commercial aviation start?

The surviving aircraft parked idle after the World War I courted the idea of conversion into cargo services to fly airmail. In that era, airmail service was the major motivation in the absence of text messages, WhatsApp, Telegram, and related modern communication technology.

Later, from 1919 to the early 1920s, commercial aviation sprang up from KLM and Imperial Airways in 1924 which is now the British Airways.

Stay tuned for more information of the somewhat twist and turns that birthed commercial aviation and how it snapped out of a rather chaotic situation to the civilisation we see in the industry.