A key lesson from history is that performance measurement/management usually leads to a disciplined focus on what is important, and this disciplined focus consequently leads to breakthrough achievements in performance. In football, for example, success is measured by scoring more goals than the opponent. Because scoring goals is important, teams typically focus on tactics that will lead to scoring more goals than the competition. Indeed, an important axiom in performance management is that “what you measure is what you get”. Cycling back to the football analogy, because goals are measured, teams that score more goals than their opponents achieve success (i.e., win the game). As more persuasively stated in another performance management axiom, “if you don’t measure results, you can’t tell success from failure”.

Despite the importance of performance measurement and management, corporate Ghana does not seem to be maximising its performance management game. This subpar performance on the performance management game is thereby impinging on Corporate Ghana’s ability to turn out breakthrough performance in the form of increased shareholder value, increased productivity, increased employment, to mention but a few.

Several examples in the private and public sectors attest to this contention of suboptimal performance on the performance management game. In the private sector, for example, the banking crisis of 2017 to 2019 that led to the collapse of several banks is still very fresh. The pervasive misappropriation of corporate resources, the fleecing of entrepreneurs by workers and several other malpractices continue to make the rounds in the mainstream media and social media.

The 2022 Auditor General’s report of countless instances of mal-/non-feasance in the public sector and state-owned enterprises also bear testimony to the lassitude in our performance management game. Indeed, the dearth of accountability, chronic low productivity and general economic malaise that the country is currently saddled with are partly a manifestation of the lack of commitment and a disciplined approach to performance management.

Considering that we take the issue of performance measurement seriously in our childhood and youthful years (e.g., with rigorous examinations in our schools), one can only wonder what the productivity benefits would have been if we carried that same zeal for measuring what is important to the corporate world. The developed countries have all benefitted from a focus on performance measurement and management.

Take the case of Japan. Back in the day, it was common for some Ghanaians to refer to low quality goods as “Japaa” (i.e., the localisation of Japan). In recent times, however, goods made in Japan are universally respected as top-quality products and every quality conscious consumer holds Japanese-made products in high esteem. While a confluence of factors may be deemed responsible for this monumental turnaround, performance measurement and management does feature prominently in the Japanese success story. For instance, when Japanese (automobile and electronics) companies started adopting performance management frameworks such as Six Sigma, Total Quality Management (TQM) etc. after World War II, the transformational effects were significant; and by the 1980s, Japanese products were becoming synonymous with topnotch quality.

We believe that Ghanaian organisations can also achieve significant performance improvements if they up their performance measurement and management game. One may ask why the assertion of laxity in performance management when some Ghanaian organisations prepare financial statements which are audited by independent external auditors?

We would like to strongly stress that financial measures are very germane, and indeed feature prominently in the performance management revolution we are calling for. However, sole reliance on financial measures can be problematical because they are largely lagging indicators of performance. For example, the Ghana Airports Company Limited (GACL) only recently published its 2021 financial results at its 8th Annual General Meeting held in April 2023.[1] You can clearly envisage the negative implications if management of the GACL were to solely rely on the financial results to help steer the company in these turbulent times.

Obviously, management would be flying blind in this high uncertainty environment; and would have limited ability to take corrective action if they were to use the 2021 results to make decisions in 2023. The consequences of such a situation need no regurgitation. Thus, since financial measures tell you what happened, they are akin to a driver only being informed of the distance travelled during a journey (i.e., what happened).

For a successful journey, the driver – in addition to knowing the distance travelled, would benefit by having information on other key variables: including knowing the condition of the car (e.g., temperature, if there are any warning lights, etc.); the state of the road (e.g., winding ‘country road’ ahead, rough road, etc.); the weather (e.g., will it rain, will it be windy); and traffic (e.g., heavy traffic, etc.).

Like the driver, we are advocating for corporate Ghana to revolutionise its performance measurement game by expanding its performance measurement frameworks to keep tabs on financial as well as non-financial measures, which together provide leading (or future-oriented) indicators and lagging (or past-/present-oriented) indicators of performance that are critical to the organisation’s short-term and long-term survival.

With lagging indicators telling how the company has performed, the leading indicators will give the company enough latitude to take corrective action before adverse events tank the company’s financial performance. Thus, organisational decision-makers, like the driver, also need to have a broad set of key metrics that help them achieve better performance. These performance measures critical to the survival of organisations have been described in various ways – including key performance indicators (KPIs), performance drivers, performance metrics, etc. In this write-up, we take the liberty of using these terms interchangeably although some might see subtle differences between them.

Over the years, various performance management frameworks have been suggested as ways forward for tracking the balanced set of financial and non-financial measures that are critical to organisational success. The Balanced Scorecard, introduced in 1992 by Robert Kaplan and David Norton[2], is one such performance management frameworks that we believe, if properly implemented, can revolutionise corporate Ghana’s performance management game and help drive breakthrough performance. This belief is predicated on the primary aim of the scorecard – which is to help organisations translate their strategies into action and align the whole organisation around relentless strategy execution. We will spend some time to provide a bit of flavour on what the balanced scorecard is and what it can do for organisations.

The Balanced Scorecard

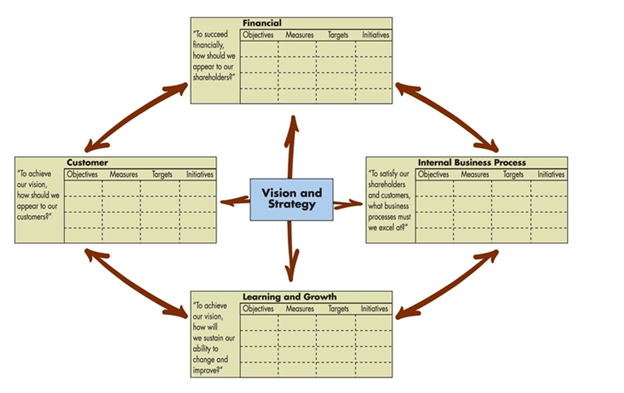

The Balanced Scorecard, which tracks the key elements of a company’s strategy, provides a balanced picture of current operating performance as well as the drivers of future performance. The scorecard includes financial measures that tell the results of actions already taken, and complements these financial measures with operational measures on customer satisfaction, internal processes and the organisation’s learning and growth activities – the operational measures that are the drivers of future financial performance. These measures together relate to a company’s critical success factors.

Indeed, widespread discontent with the use of traditional financial measures by the 1980s led to some corporate executives calling for the abandonment of financial measures in favour of actionable operational measures, while other executives called for enriching financial measures to make them more relevant. Caulkin (1997), for example, cites a US Institute of Cost Management Accountants study that found “nearly two-thirds of companies are losing faith in accounting-based performance measures, and are seeking new ‘value criteria’ to get a better handle on their businesses”.[3]

In fact, Kaplan and Norton (1992) asserted that “traditional financial performance measures worked well for the industrial era, but they are out of step with the skills and competencies companies are trying to master today”. The balanced scorecard, one of the most important panaceas to the dissatisfaction with financial measures, was introduced following a year-long research with 12 companies – whereby Kaplan and Norton persuasively made the case for incorporating both financial and operating/non-financial measures instead of choosing between financial and operating measures.

While the balanced scorecard is flexible enough for the incorporation of operating measures along any dimension critical to the success of an organisation, the operating measures are typically related to: (i) measures that demonstrate value to the customer; (ii) measures that show robust internal business processes; as well as (iii) measures that indicate continuous organisational learning and growth.

Kaplan and Norton have suggested that the Balanced Scorecard should be thought of as the dials in an airplane cockpit; it gives managers complex information at a glance. The complexity of managing an organisation today requires that managers be able to view performance in several areas concurrently. The balanced scorecard makes this possible by allowing managers to look at the business from four important perspectives, thus providing answers to four basic questions as exemplified below:

- The customer perspective: How do customers see us? How can we show we are delivering to customers the value they expect? This perspective helps organisations ensure that they continue to meet the needs and expectations of their customers – since no successful organisation can exist without customers.

- The internal business perspective: What processes must we excel at to deliver value to our customers? This perspective ensures that organisations excel in their internal business processes in order to satisfy their customers’ needs and expectations.

- The learning and growth perspective: Can we continue to improve and create value? What actions must we take to prepare the people and organisation for the future? Measures in this perspective will necessarily ensure that organisations continue improving their ability to meet customers’ expectations and to create value for them in the future, or else their long-term survival could be jeopardised.

- The financial perspective: How do we look to shareholders? How can we show our strategy is succeeding financially? Performance measures in this perspective ensure that operational successes are translated into financial success.

Indeed, the Balance Scorecard helps organisations achieve the RAISE philosophy espoused by CPA Canada (i.e., Resilient + Adaptive + Innovative = Sustainable Enterprise). By providing visibility into past, present and future indicators of performance, the balanced scorecard helps create sustainable enterprises that are resilient, adaptive and innovative. The balanced scorecard elegantly postulates that for an organisation to be able to succeed financially, it must continue to excite its customers about its products and/or services. However, to excite its customers, the organization needs to have solid internal business processes, systems and the culture to deliver added value to customers.

While solid internal business processes will help the organisation deliver value to customers now, it can only continue delivering value to customers in today’s tumultuous business environment if it is an innovative and learning organisation. This simple logic elegantly summarises the modus operandi that organisations (be they private, public, governmental or non-governmental) need to uphold if they are to create long-term value for their stakeholders. The four perspectives of the balanced scorecard are presented in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Perspectives of the Balanced Scorecard

More importantly, the Balanced Scorecard contends that achieving breakthrough performance may remain elusive unless organisations link their performance measures to their strategic mission, vision, goals, objectives and critical success factors. This is really very important. Randomly selecting performance measures will not do an organisation any good unless those measures are aligned to corporate strategy, mission, vision, objectives and critical success factors.

This alignment establishes a clear line of sight from strategy to day-to-day operations, and ensures that all the organisational performance management ducks are in a row and ready to propel the organisation to performance bliss. Figure 2 shows the tightly coupled linkages that Kaplan and Norton contend must feature in strategy execution and corporate performance management systems.

Figure 2: Balanced Scorecard Strategic Performance Management System Linkages

Thus, for strategy execution par excellence, organisations need alignment between their mission, values, vision and strategy. The strategy is then translated into cause-and-effect relationships (usually through a strategy map) which lend themselves to measurements through the balanced scorecard. Strategic initiatives are then agreed upon and the corporate-wide balanced scorecard is subsequently cascaded down organisational levels all the way to employee/personal level. This tight alignment helps the organisation achieve its strategic outcomes in the form of a motivated and prepared workforce, effective business processes, delighted customers and satisfied shareholders/stakeholders.

The Balanced Scorecard’s appeal – as a best-of-the-breed performance management framework that propelled countless organisations to performance excellence – has led to its widespread adoption among companies of all sizes and in all industries, including the private, public and non-governmental sectors. The popularity and effectiveness of the Balanced Scorecard in helping organisations achieve breakthrough performance in developed and emerging countries partly motivated introduction of the Balanced Scorecard Hall of Fame, which recognises the very best companies that have relied on the Norton and Kaplan Balanced Scorecard framework to successfully execute their organisational strategies. Undeniably, winners of the annual Balanced Scorecard Hall of Fame awards are a who’s who of bellwether organisations; including Cisco, BMW, Hilton Hotels, Chemical Bank (now JPMorgan Chase), U.K. Department of Defence, Hospital for Sick Children, Infosys, etc.[4]

Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) must be SMART/SMARTA

Since we have talked a bit about getting performance measurement right, it is important to highlight some important features of the performance measures that can help organisations. The key performance indicators/goals/measures that can help Corporate Ghana achieve breakthrough performance need to be SMART or SMARTA (i.e., specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, time-bound and aligned).

- S – Performance measures need to be specific to the organisation or employee, to increase the likelihood of exacting the required behaviour. Measures that are expressed in general or in vague terms will be difficult to nail down.

- M – Knowing if performance expectations/goals are being achieved requires that KPIs are measurable. As one of the performance management axioms states, “what you measure is what you get”. Quantified KPIs also provide feedback for the organisation or employees with respect to the quality of their performance.

- A – For KPIs to engender the right effort, there must be consensus that objectives are realistically achievable. In other words, the organisation or employees must have the required skillsets and resources to achieve the desired outcomes. Accountability cannot be exercised if organisational participants do not have control over the achievement of measures that they are responsible for.

- R – KPIs need to be relevant to the organisation or employee, and must be linked to the mission, vision, objectives and goals of the organisation.

- T – High-performing organisations have performance goals that are time-bound. A task well executed after its expiration date adds no value to the organisation.

- A – Performance measures must be aligned to corporate goals, objectives, vision, mission and employee compensation. To avoid “the folly of rewarding A while hoping for B”, measures of performance need to be aligned to the reward system, vision and goals.

Suggested Implementation Steps

To ensure successful implementation of a breakthrough performance management framework like the balanced scorecard, having a disciplined approach is necessary. Below are some suggested implementation steps that organisations desirous of implementing the balanced scorecard ahould follow:

- Form a balanced scorecard committee. The committee must be a cross-functional one with a broad array of experience. The project champion should be a dynamic senior manager. As Drtina noted, “to overcome the inertia of traditional thinking and established processes”, the balanced scorecard project champion needs to be dynamic to “inevitably take on the roles of designer, motivator, salesperson and diplomat”.[5]

- Get the buy-in of top management and everybody. This may require the committee responsible for implementing the balanced scorecard to deliver a series of seminars/presentations on the importance of performance measurement to help get buy-in.

- Agree on and align corporate mission and strategy. This will require tapping into the collective intellect of the organisation by involving its key personnel and a representative cross-section.

- Develop the measures, which may require several iterations, to get the final critical set. The measures should be: (i) financial and non-financial; (ii) reflective of long-term and short-term objectives; (iii) complete and controllable; and (iv) should track the four important perspectives to organisational survival – financial, customer, internal business, learning and growth.

- Refine the measures and establish cause-and-effect links to achieve the greatest impact on corporate objectives. The cause-and-effect relationships are important because they will force the organisation to explicitly think about how the measures actually impact corporate objectives.

- Cascade the scorecard to departments and employees. To ensure that everyone is contributing to organisational success, it is imperative to cascade the organisational scorecard to departments and employees so that everyone knows how their part of the work impacts the organisation’s overall success. The motivational effects of cascading the scorecard downward can be significant.

- Link corporate incentives to the scorecard. The Balanced Scorecard’s aim is to harness organisational human resources to achieve breakthrough performance. Linking the scorecard to corporate compensation will focus energies on achieving what matters to the organization, and help avoid the “folly of rewarding A while hoping for B”.

While the expectation is that organisational participants will work to improve performance, it is important to emphasise that organisational members who are not pulling their weight also need to be negatively rewarded or punished. Forbes (2023) for example sites several marquee companies (e.g., Meta, Salesforce, Amazon, Google, etc.) that laid-off employees identified as low performers based on performance reviews.[6]

Having this disciplined level of reward and punishment systems in corporate Ghana would significantly improve accountability and would have, for example, likely meant that the billions of cedis misappropriated as reported by the Auditor-General would have led to the culprits being held accountable – and appropriate action taken to retrieve the loot.

- Get necessary technological infrastructure to track performance. Unless a company has a system of recording and tracking corporate performance, it will be difficult to tell if performance objectives are being met. While there are specific software products that are appropriate for tracking balanced scorecard metrics, there are also ‘free’ software products (e.g., Excel and Power BI) that can also do a decent job of reporting performance.

Avoiding some pitfalls with a Balanced Scorecard

It should be noted that not all balanced scorecard implementations are successful. Studies indicate that around one-third of balanced scorecard implementations fail. Below are some factors to watch out for if organisations are to avoid being part of the unsuccessful group.

- Lack of organisational buy-in. By nature, many humans resent measurement. Even in organisations with robust performance management engrained in their corporate cultures, there is resistance. Amazon, for example, is being accused by employees of “using an opaque ‘rank-and-yank’ performance reviews to cull its workforce”.[7] Organisations should therefore not assume that everyone will embrace a (new) performance management system. Contrarily, many may resist the system because of perceived potential losses.

Some may indicate their work is so complicated that it does not lend itself to measurement. If one’s work is so complex as to be immeasurable, then it may be symptomatic of the employee lacking knowledge of his/her work to be able to break it down into quantifiable work units. Others may try to game the system or skirt it all together. Indeed, management needs to do all it can in its power to get the buy-in of everyone.

- Lack of top management support. A balanced scorecard initiative is likely doomed to fail if there is no support from top management. The balanced scorecard links day-to-day operations with mission and strategy. Since mission and strategy are the forte of top management, getting top management support is critical to a balanced scorecard initiative.

- Failure to use and/or enhance the balanced scorecard. Some organisations may fail to use the balanced scorecard or fail to see it as a living document that may require evolution as the business environment evolves. Such tendencies can torpedo the successful deployment of a balanced scorecard initiative.

- Metrics paralysis. The tendency to ensure that every angle is covered sometimes leads to balanced scorecards that are stuffed with an overwhelmingly large number of metrics. A best practice on scorecard development is to ensure that there are no more than twenty (20) measures in the scorecard. This means organisations must spend time to identify only the key metrics that can propel them to performance nirvana.

- Incorrect metrics. The use of flawed and incorrect metrics will marginalise a balanced scorecard implementation, because the incorrect metrics will invariably direct organisational efforts to the wrong strategic goals and objectives.

The above are some pitfalls to avoid when implementing balanced scorecards. Given the importance of the balanced scorecard in catapulting organisations to breakthrough performance, every effort must be taken to ensure a successful deployment if an organisation makes a commitment to breakthrough performance. It is sometimes recommended that organisations retain the services of an experienced consultant to guide them through implementation and internalisation of the scorecard initiative.

An illustrative example of a Balanced Scorecard

To wrap up our discussion of the balanced scorecard, we will assume that the AfricaBestArtCompany is a Ghanaian company that sells premium African art through its online store. To simplify the example, we are assuming that our strategic objective is to create stakeholder value which would require revenue growth and cost management. Our focus will be how to build a simple scorecard that deals with the revenue growth strategic objective.

To do this, we will first translate the revenue growth strategic theme along the balanced scorecard’s four perspectives using a strategy map, which essentially helps us establish cause-and-effect relationships among the various elements of this strategic theme. Figure 3 is a sample balanced scorecard for our hypothetical company.

Figure 3: Sample Balanced Scorecard for the AfricaBestArtCompany

As the strategy map in Figure 3 exemplifies, to achieve our revenue growth strategic theme we must have strategies to attract new customers, retain our existing customers and increase customer satisfaction. We believe that we can meet these customer expectations if our internal business processes allow us to be cost competitive, deliver timely service and offer topnotch product quality. Finally, in order to consistently deliver value to customers and create value for our stakeholders, we need to be a learning and growth organisation – which can be achieved through strategies for employee development, technology leadership and organisational renewal.

Once we have created the cause-and-effect relationships through our strategy map, we can now determine the scorecard measures that will unambiguously allow us to track whether or not we are successfully executing on the various strategic goals. As already indicated, only meaningfully important measures that track the strategy should be incorporated into the scorecard.

For this example, we have determined that we will use Revenue per Product as a measure of our revenue growth strategic objective. With respect to our customer perspective strategic goal of attracting new customers, we will use Customer Conversion Ratio as a measure while Customer Retention will be used to measure our strategic goal of retaining existing customers.

For our customer satisfaction strategic goal, we will use the % of Product Returns as a measure. For the internal business perspective, we will use Cost per Customer to gauge achievement of our strategic goal of being cost competitive. Providing service in a timely manner will be measured using % Online Store Availability, and providing topnotch product quality will be measured by # of Defects per 1,000 Units. Finally, to track how we are poised for long-term success through the learning and growth perspective, we use $ Training Budget per Employee to measure the strategic goal of employee development, $ IT Spend to measure the strategic goal of technology leadership and % Training Participation Rate to measure organisational renewal.

Once we have translated our strategy and identified the best measures for each strategic goal, we can then add important attributes to our scorecard: including what our target is each measure – baseline, actual, etc. We can also add the initiative(s) that we intend to undertake to achieve each strategic objective. The scorecard thus becomes an execution document as well as a reporting document, indicating not only the execution pathway to success but also how we are progressing with respect to the achievement of our objectives.

Conclusion

Ghana needs all hands on deck to propel it to greater heights. While policymakers and other stakeholders are all working toward improving the lot of citizens, we believe that corporate Ghana can also benefit from reminders of how productivity can be improved. In this ‘Management Education Series’, we hope to provide some of those reminders. We start the series with how the Balanced Scorecard, which has helped countless organisations achieve breakthrough performance over several decades, can also help corporate Ghana achieve breakthrough performances. Stay tuned for other reminders in due course.

[1] See https://www.gacl.com.gh/publications/8th-agm/.

[2] See Kaplan, R.S. & Norton, D.P. (1992). “The Balanced Scorecard – Measures that Drive Performance.” Harvard Business Review, January-February, pp. 71-79.

[3] See Caulkin, S. (1997). “Business (Management): Stampede to replace the principle of profit – Accounting-based performance measures are being abandoned in the quest for shareholder value”. Observer [London, England], 12 Jan. 1997, p. 9.

[4] See past winners at https://thepalladiumgroup.com/awards-program/past-winners-hall-of-fame.

[5] See Drtina, R. (1999). “No Joke – Performance Measures can Deliver.” Strategic Finance, pp. 47-50.

[6] See https://www.forbes.com/sites/jackkelly/2023/02/13/adding-insult-to-injury-being-labeled-as-a-low-performer-makes-matters-worse-for-laid-off-workers/?sh=6925f8b86bb8

[7] See https://www.latimes.com/business/story/2022-01-10/amazon-is-focus-of-push-to-curb-rank-and-yank-worker-ratings.