Centre for Applied Research and Innovation in Supply Chain-Africa (CARISCA), Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi-Ghana

Key Highlights from a Recent Study from the Center for Applied Research and Innovation in Supply Chain Africa (CARISCA)

- Only 31% of supply chain actors who sought financing were successful in obtaining it.

- Limited access to collateral security is a major barrier for supply chain actors in accessing funds from formal financial institutions.

- Default risk poses a significant challenge to sustainable supply chain financing in the agricultural sector.

CARISCA’s Recommendations

- Group (pooled) financing through a common digital platform is recommended to enhance sustainable financing in the maize supply chain.

- The government’s involvement and legislation, along with education and support from financiers, community leaders, and farmers, are crucial for the success of the proposed financing scheme.

- A stable and regulated financing ecosystem will contribute to changing livelihoods and economic development in Ghana’s agricultural sector.

Introduction

Sustainable food supply chains are very crucial for Ghana’s socio-economic development and food security. Agricultural supply chains are a major source of employment, foreign exchange and household incomes, as well as food and nutrition security in Ghana. Despite the huge potential of the food supply chain in the country, operations of key chain actors are severely constrained by inadequate financing, resulting in sub-optimal performance and uncompetitiveness in the global market. At present, Ghana depends considerably on food imports (e.g. rice, wheat, chicken, etc.) to feed its population. There is an urgent need for massive increases in agricultural productivity and improvement in the performance of intermediaries within the agricultural supply chain.

Safeguarding food security is a critical aspect of Ghana’s development, and securing sufficient funding plays a pivotal role in this endeavor. Over the years, the Ghanaian government, in collaboration with various stakeholders, has placed great emphasis on enhancing food security, recognizing its profound impact on national stability, economic growth, and the overall well-being of its citizens. Ghana’s commitment to achieving food security has been manifested in its policies and initiatives aimed at improving agricultural productivity, promoting sustainable farming practices, and ensuring access to nutritious food for all its citizens. However, these endeavors require substantial financial support to realize their full potential and make a lasting impact.

Over the years, successive governments of Ghana and other stakeholders have introduced a series of interventions and enacted policies to ensure an adequate and sustainable financing sector and accelerate growth in the agricultural sector. However, poor targeting and implementation challenges have caused many such interventions to achieve only marginal successes. The poor results registered by previous financing projects have been attributed to a top-down approach in policy formulation, resulting in less than satisfactory relevance, less cost-effectiveness, and poor ownership1. It is therefore not surprising that agricultural financing remains a major issue in Ghana despite previous efforts.

Access to adequate financing for farmers, aggregators, processors and traders in the food supply chain is key to unleashing the great potential of the Ghanaian agricultural sector. Financing the agricultural supply chain in Ghana dates back several decades, but the structure has seen very little innovation. Funds for agricultural operations have often been provided through interventions from the country’s government, loans via the financial sector, donor funds, family heritage, and individual savings, among others. Adequate, timely, and sustained financing is crucial for the growth of the agricultural sector in Ghana, mainly for working capital to acquire inputs (e.g. seeds, fertilizer, herbicides, labor, etc.) and the acquisition of fixed assets for operations (e.g. land, tractors, planters, combined harvesters, warehouses, etc.). The absence of financing therefore limits the average acreage of cultivated farmlands as well as the movement of produce along the supply chain, thereby impeding agricultural growth with significant consequences for food and nutrition security.

This policy brief draws useful lessons from a field survey undertaken by CARISCA to make useful recommendations to improve access to financing for key supply chain actors in the maize sector in Ghana. Maize is an important food security crop cultivated by almost all farming households in Ghana and consumed widely across the country in different diet types. Therefore, sustainable financing of the maize supply chain will lead to significant improvement in Ghana’s food security status.

The Study Approach

The Centre for Applied Research and Innovation in Supply Chain-Africa (CARISCA) at the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology commissioned a study into agricultural supply chain financing in Ghana using maize as case study. The field survey covered 488 supply chain actors (250 farmers and 238 intermediaries) across five major maize-producing districts in Ghana, namely: Ejura Sekyeredumase, West Akim, Upper West Akim, Wenchi, and Kintampo South. Supply chain actors were selected through a combination of purposive, simple random and snowball sampling techniques. Data collection was done through personal interviews; focus group discussions and key informant interviews were also conducted in selected communities to obtain data for the purposes of triangulation. Field data were analyzed using descriptive tools, simple narrations and regression modelling to assess how accessibility, appropriateness, default risk, and financing structure relate to sustainable supply chain financing.

Key Findings

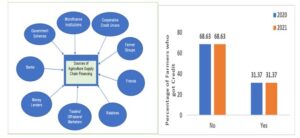

As shown in Figure 1, the main sources of agricultural financing are banks, government schemes, microfinance institutions, credit unions, farmer groups, money lenders, traders, relatives and friends. The study found that only 31.37% of supply chain actors who sought credit got financing (Figure 2). Chief among the reasons for not getting credit was the inability of supply chain actors to provide collateral security (Figure 3). Financial institutions in Ghana require collateral security in the form of land and buildings with proper documentation, as well as cocoa and any other plantation crop. In most cases, farmers do not have proper documentation covering their lands. The types of buildings owned by supply chain actors also do not usually qualify as collateral security for bank loans. This makes it difficult for farmers and other supply chain actors to access financing from formal financial institutions in Ghana. The actors are left with no option than to rely heavily on family and friends as the main source of credit. The amount of credit obtained from this source is usually too small to make any significant impact on supply chain operations.

Fig 1: Sources of Maize Supply Chain Financing Fig 2: Percentage Who Got Financing

Table 1 shows the requirements for accessing financing in the maize supply chain. Table 2 shows the rigid nature of the structure of maize supply chain financing. We solicited views from financiers on the challenges of financing agriculture; the issue of default was ranked first among several challenges. As posited by a banker: “Our financial institution does not want to deal with farmers; most of our challenges are as a result of us giving financing to farmers in the past”. To probe further, we sought to know the main cause of default, which was revealed to relate to misapplication of loan funds (Table 3),

Results from further econometric modelling showed that default risk and financing structure are significant challenges to sustainable supply chain financing. However, accessibility and appropriateness were found to be significant enhancers of sustainable supply chain financing in the maize sector.

Policy Recommendation

“Is a Pooled Financing Scheme through a common digital platform the way forward?

Group (pooled) financing through a common digital platform appears to provide the best opportunity for sustaining financing in the maize supply chain. Group (pooled) financing is used here to refer to a system where financiers in the Agricultural Supply Chain financing ecosystem come together to form a digital platform/consortium where funds they intend to make available for financing agricultural activities are put together (pooled). Under the scheme, all individuals, groups, and institutions seeking funds for their agricultural supply chain activities apply through this common digital platform. This digital platform will provide sufficient financing for all actors since it involves a pool of financiers who will put together all the resources at their disposal. Further, issues of default will be reduced since the platform will require all members to be registered and detailed background checks performed. Further, financial seekers will not be able to engage in loan shopping when such a platform is introduced. The financing will be structured in such a way that it will take into consideration the kind of business to determine repayments, among others. Since this platform will be an agricultural supply chain targeted scheme, it will consider the particular characteristics of agribusiness, making the scheme appropriate for all actors.

To actualize this pooled financing scheme described above, we recommend the following:

- The Ghanaian government must take responsibility and enact an act of parliament to set up a digital platform that financiers can subscribe to. This should provide effective and efficient regulatory guidelines for the platform’s operations. Tax incentives should be used to encourage financiers to join the consortium. The control of the digital platform should be vested in a committee to be set up by the members of the consortium and supported by the enactments. This platform could be managed by a centre like CARISCA set up in an institution of higher learning with strong collaboration with the Ministry of Food and Agriculture (MoFA) through its regional and district offices.

- The government of Ghana should also take responsibility for providing the initial extensive education required for the operations of such a scheme to be understandable to all actors in the agricultural supply chain through the National Council for Civic Education (NCCE). This education should be sustained until there is a full understanding and acceptance of the system.

- Financiers need to take an interest in and be committed to ensuring the success of such a consortium; this is because they have a double benefit to achieve from such a system. First, the system will enable them to reduce default rates due to loan shopping and change of status. Second, they will be able to provide the level of financing needed by the agricultural sector since the default rate will reduce across the board. The added benefit of this move for financiers is that they will be able to protect depositors’ money and generate more value for shareholders.

- Community leaders must see their participation and support for such a consortium and platform as a duty call. This is because appropriate, adequate and reliable financing holds a big promise for changing the livelihoods of the members of their communities as well as the economic development of the nation

- Farmers owe a duty to themselves to realize that it is in their interest that there is a stable, regulated and reliable financing ecosystem for agricultural activities. Farmers are expected to register with the consortium so that any time they need a loan to fund their farming activities, they can obtain it easily without the usual issues.

- The sustainability of the maize supply chain is a shared responsibility for all actors along the supply chain. Input suppliers, off-takers, traders and marketers need to actively support such a platform and the consortium because it will build trust along the chain, eliminate fraudulent farmers and other actors who undermine the financing capacity of the chain, and also ensure the availability of enough funding to support maize production.

Authors:

Abdul Samed Muntaka

Isaac Akurugu Apike

David Antwi

Dorcas Nuertey

Robert Aidoo