As the formalisation of the creative industries increases in this part of the world, it is likely that young artists and the general public alike have been coming across the concept of ‘intellectual property’ a lot more. Based on the World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO) definition, ‘Intellectual Property’ (IP) refers to the ‘creations of the mind, such as inventions; literary and artistic works; designs; and symbols, names and images used in commerce’. It may come as a surprise that these somewhat intangible assets created by artists and non-artists alike are also subject to regulations, frameworks and even disputes in the same way that physical property can be. This is where IP law comes into play to ensure the protection of such through patents, copyright and trademarks. When enforced, the law operates within the space of protection, but also exists to ensure the recognition and financial benefit of one’s intellectual property.

Intellectual property in Ghana

For this edition, I had the pleasure of speaking with Carla Olympio, Founder and Managing Partner of Agency Seven Seven, based here in Ghana. In their work to offer professional services to SMEs and creatives, they also help with start-ups, brand management and IP. A good basis for the conversation is to understand that the law exists in everything. Carla expands: “There’s no aspect of business or the economy or of life where the law is not required”. This is especially true for creatives and artists who are intent on operating in a professional capacity and not a hobby. Once the creative output is strategic and income generating, it is essential that practice also considers the same factors many other businesses do in operations and legality.

In Ghana, the main regulations that relate to Intellectual property are:

– The Copyright Act, 2005 (Act 690), which refers to protect original works of authorship as soon as an author fixes the work in a tangible form of expression.

– The Patents Act, 2003 (Act 657), which is an act to provide for the protection of inventions and other related matters.

– Trademarks Act, 2004 (Act 664) pertains to the protection of inventions, symbols or words legally registered or established by use as representing a company or product.

– The Industrial Designs Act, 2003 (Act 660) to enhance the protection of industrial design, which includes things which – in the appearance of a product – cause an aesthetic impression.

– The Protection Against Unfair Competition Act, 2000 (Act 589), which is to provide the affected person with certainty that their rights will not be further jeopardised and the defective state removed.

In 2016, a campaign was launched by the government, entitled The National Intellectual Property Policy and Strategy, which sought to strengthen the deployment and enforcement of IP frameworks as well as raise awareness. Although the afore-mentioned acts do exist to protect trademarks, patents and designs, it would appear that activity on this particular campaign has stalled.

Local perceptions

The general consensus within the sector is that that the implementation of laws around IP is weak, and there is still a lot of sensitisation work to be done around value. Carla elaborates further: “When people think of creativity and the arts, they can often downplay the importance of ownership and protection. However, this is actual property. If you ask a creative in Ghana – for example, a filmmaker or a musician – what they need to grow their craft, they will mostly answer: “money” or “funding”. However, just like a builder will find it difficult to raise funds if they cannot show good title to the land, no one will fund you if you do not or cannot show good title to your creative output. I tell people that it may be an intangible property but by the law, it is property”. This can be challenging to grasp in a culture and society where copying and piracy are rife, and in some cases can even be considered as homage to the original. Once this concept is established, it would mean that the property has an owner, so it cannot be used without appropriate permission and/or payment – if used at all. Carla advises artists and creatives to become conversant with this information and get involved in rights organisations, such as GHAMRO or ASCAP, that can help to this end.

On the side of the artists, other challenges can arise when measures are not taken to formalise and protect their work and or businesses. This can take the form of trademarks, patents, copyrights, lawyer-drafted contracts, etc. Led by the heart and a decent amount of passion and natural talent, many creatives can sometimes lack the knowledge or business acumen required on the operational side. In the absence of personnel to manage this, especially with smaller entities, this can ultimately become more costly in the face of issues.

Thinking globally

It is essential to consider global positioning and research when venturing into foreign markets to ensure your IP is adequately protected. In other instances, there are artists and creatives who may be focused on producing and operating locally, but can be thrust on a global stage involuntarily, especially with the ease of archive and distribution through digital channels.

To cite an example, earlier this year, Ghanaian Hiplife icon Obrafour sued Canadian Hip Hop star Drake for US$10million in damages. The charge? Use of a sample without permission; in effect, unauthorised use of intellectual property. Drake’s 2022 song ‘Calling my Name’ featured a clip of Obrafour’s 2003 song ‘Oye Ohene’. Prior to the release of Drake’s album, an email was sent from his team informing Obrafour that the sample had been used alongside a request for permission to release it. There was no response ahead of the release of the album – which was just 9 days later. This particular incident opened up a whole range of dialogue around IP and ownership, especially with regard to the song owner vs the sampler vs the artist whose voice was used on the song. Bearing in mind that the original song was also registered under US IP law, this demonstrates just how complicated the world of enforcement can be when it comes to IP.

Though nuanced, IP issues are certainly not limited to this part of the world alone. It is, however, essential and most effective to have your ‘ducks in order’ and be prepared, Carla advises. Register your IP and ensure you have well-written, appropriate contracts. Though there is still a long way to go in terms of implementation, the better-equipped one is with business formalities around their craft, the more likely a ‘win’ will be in any battles to protect or enforce appropriate compensation.

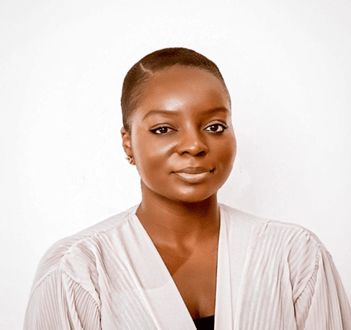

About the author:

Ama Ofeibea Tetteh is a Creative Consultant and founder of Chapter54, a boutique consultancy which exists to help bolster African Creative Economies through research and programming.

Email: [email protected]

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/ofeibea