Discussion in the preceding section affirmed transactions of Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies were mostly unregulated. However, the trend has reversed or improved in recent years. The anti-money laundering (AML) and counter terrorism financing watchdog for the global community, Financial Actions Task Force (FATF), has set rules for the cryptocurrency industry.

So far, the following selected economies across the globe have considered and adapted regulations to forestall any financial tsunami by the digital financial exchanges on individual and corporate investors: Australia, Canada, China, European Union (EU) and the United Kingdom (UK), Ghana, India, Japan, Nigeria, Russia and Belarus, Singapore, South Africa, South Korea, Switzerland, United Arab Emirates (UAE), United States of America (USA), Venezuela and Zimbabwe, among others.

A common belief held among these economies is the urgent need for them to take proactive steps to protect the investment purse of their citizens and foreign investors in their respective jurisdictions. This initiative is expected to improve the issue of lacking effective control over the activities of traders in Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies in the virtual currency markets.

Brown and Whittle (2020) noted individual economies have been late in their respective responses to challenges posed by the global cryptocurrency industry. However, their “late” responses have been dramatic and powerful. In the following section, we continue with the brief explanation on regulatory measures adapted by each of the above-listed economies.

Venezuela

Between 2016 and early 2017, there were no clear-cut laws regulating cryptocurrency trading activities; the status of Bitcoin and altcoins in the financial markets was not clearly defined in Venezuela. The void in financial regulations allowed law enforcement officials to subject the virtual financial market in the country to abuse and corruption (Aguilar, 2020).

To restore sanity and restore investors’ confidence in the country’s financial system, in 2017 the Venezuelan government compiled a detailed registry of digital currency miners as a significant step toward controlling digital currency activities and arresting the Venezuelan bolivar’s free-fall.

As at December 2017 the Venezuelan bolivar was virtually unusable, following international restrictions and sanctions imposed on the regime of President Nicolás Maduro by advanced economies such as the United States of America (Ashley, 2018).

In order to liberate Venezuela’s economy from the shackles of international restrictions, the President Nicolás Maduro-led government announced the introduction of a digital currency called petro – which was backed by the country’s oil.

The state-approved cryptocurrency could allow Venezuela to become a strong force to reckon with in the world of digital currencies; it could allow Venezuela to emerge among global economies with progressive regulations on virtual currencies (Nelson as cited in Ashley, 2018).

On 21st September 2020, Venezuela officially legalised and gazetted (Official Gazette No. 41,969) mining of Bitcoin. This initiative further placed the country on the global radar of economies – notably after Japan, China, Canada, Singapore and others – to have officially reccognised cryptocurrencies including Bitcoin as viable income-generating sources.

Authorities in Venezuela believed legalising Bitcoin mining could boost economic growth through increased incomes. Although Venezuela has succeeded in drafting a legal framework to regulate Bitcoin and altcoins trading, Aguilar (2020) noted the framework is embedded with gaps and inconsistencies.

These gaps and attendant inconsistencies have paved the way for corruption to dominate existing legal frameworks. These setbacks notwithstanding, Venezuelans’ appetite for investments in cryptocurrencies including Bitcoin is on the increase; the virtual exchange market in the country is gaining ground as more Venezuelans aspire to obtain American dollars to trade for bolivars.

Zimbabwe

In May 2018, the financial services regulatory authority in Zimbabwe, known as the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (RBZ), banned transactions including payments processing between cryptocurrency firms and banks. However, reports carried by the Zimbabwean local newspaper, The Chronicle (as cited in Khatri, 2020), revealed of the Zimbabwean central bank’s admission of the fact that the crypto trend is a reality.

Following this realisation, the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe took steps to draft a policy framework to guide operations and activities of virtual currency operators in the country. In effect, the central bank considered factors such as economic need to lift the ban on cryptocurrency trading in the country.

The framework, known as the Fintech framework, is expected to be well-structured to assess virtual currency firms and their mode of operation in the country. The assessment outcomes will inform the regulatory body’s decision on cryptocurrency trading in Zimbabwe, a country embroiled in economic challenges in the last few years.

Successful investments in digital currency trading could assuage the financial ‘pain’ endured by investors in the Zimbabwean economy over the last few years. However, this investment feat is predicated on a number of factors – including enactment of regulations that will ensure due diligence and protect funds of investors from the exploits of virtual exchange operators and predatory cyber-hackers.

Concluding Remarks

The Financial Actions Task Force comprised more than thirty-seven member-countries as of 27th March 2020. These included the United States and United Kingdom, while many more countries were expected to sign up and align their respective financial services legislations with standards set by the Financial Actions Task Force.

Member-countries had until June 2020 to review their existing financial services legislations and align with FATF standards. This explains on-going policy reviews by some economies including Germany, France, United Kingdom, United Arab Emirates, South Korea and Zimbabwe, among others, in recent periods. New standards set for virtual currency exchanges and their related businesses are explicit; and these rules are expected to facilitate transactions between virtual currency operators and banks. This opportunity extends to individual and corporate investors in the cryptocurrency markets (Salami, 2020b).

As stated earlier, hackers who hack into blockchain and related systems to steal virtual currencies operate with technological sophistry. These hackers have the technological ability to fake their identity and location, and to apportion blame on innocent third parties. Besides, it is quite a herculean task to trace stolen digital currencies to a logical conclusion.

Even where the perpetrators are traced to a particular jurisdiction, without identifying the ‘real’ actors, it is difficult to file for compensation against the jurisdiction or country at the international level. Finlay and Payne (2019) identified attribution as a major challenge to ‘aggrieved’ countries in international law.

Current provisions in international law stipulate that for a country to be accused of any wrong-doing, the ‘offended’ country must be able to establish attribution. That is, it should be able to demonstrably attribute the act to the ‘accused’ country. An act can be attributed to a country when any of its organs including officials, government or departments is involved.

Although governments of many economies do not approve of cryptocurrency trading activities, it may be difficult to attribute cyber-attacks on virtual exchanges to them. Further, actions of non-state actors (persons not directly employed by the country) cannot be attributed directly to the country unless it can be established that these private individuals or groups’ activities have been sanctioned by the country through adoption of their conduct, or control of their activities.

Recent judgements by the International Court of Justice on cyber-attacks revealed the principle of effective control must be established when seeking attribution. However, the establishment of attribution does not bring the legal complexities in international law to an end; other mechanisms must be implemented – including allowing an effective response from the accused country.

Finlay and Payne (2019) noted proof of hackers’ geographic location, and proof of financial equipment and aid used by system-hackers, may not suffice to pass the litmus test of effective control in international law. The legal provisions in international law make it difficult for any country to be held openly liable for cyber-attacks on virtual exchanges.

Perhaps, the Financial Actions Task Force’s role in global financial regulations may increase the responsibilities of countries to investors in the virtual exchange space. Fortunately, countries such as Japan, Singapore, South Korea, France, Germany, United Arab Emirates and others are responding favourably. This assurance of protection by the state could serve as incentive and morale-booster to existing and potential investors in virtual currency markets across the globe.

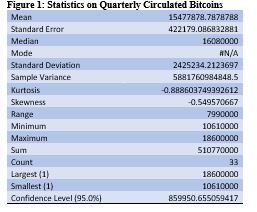

Statistics – Descriptive

This section presents a summary of Bitcoins circulated on quarterly basis during the research period. A statistical summary of total Bitcoins circulated quarterly from 2012 through 2020 and included in the analysis is presented in Figure 1. Analysis in the figure drew on data in Table 1, column 2; and Figure 2. Data in Figure 1 indicate the respective sample variance (5881760984848.5) and skewness (-0.549570667) for the distribution.

The value for sample variance (5881760984848.5) tells us the expectation of squared deviation of the research random variable from its mean. Skewness explains the distortion or asymmetry of the random variable around the mean in the distribution.

The statistical data depict respective Kurtosis and standard error values of -0.888603749392612 and 422179.086832881. The extent to which the coefficients are significantly different from zero is explained by the standard error value. The minimum value in Figure 1 is 10,610,000. This represents total Bitcoins circulated during the fourth quarter of 2012.

The maximum value (18,600,000) is representative of total Bitcoins circulated in the fourth quarter of 2020. The range explains the difference between maximum and minimum values for the distribution. Value for the range (7990000) in Figure 1 explains the substantial difference (7,990,000) between the respective total Bitcoins circulated in the fourth quarter of 2020 (18,600,000); and the total number circulated during the fourth quarter of 2012 (10,610,000).

The value for sum (510,770,000) in Figure 1 depicts the total number of Bitcoins circulated during the period and included in the analysis. This value is significant relative to the estimated total number of mined Bitcoins (21,000,000) available for circulation on various virtual exchanges across the globe.

As of 11th December 2020, Ycharts (2020b) estimated daily Bitcoin transactions at 311,657. The respective average costs per Bitcoin transaction and ethereum transaction were US$51.910 and US$2.394. This suggests the average cost per Bitcoin transaction was about 21.68 times (US$51.910 ÷ US$2.394 = 21.683375 = 21.68) the average cost per ethereum transaction during the period.

Similarly, total number of circulated Bitcoins as of 31st December, 2020 was estimated at 18.6 million; meaning there were 2.4 million (21 million – 18.6 million = 2.4 million) Bitcoins outstanding. Total number of Bitcoins mined and circulated (18.6 million) was equivalent to 88.6% of all mined Bitcoins (21 million), while the number in the coin vault or outstanding (2.4 million) was equivalent to 11.4% of total mined Bitcoins (Faridi, 2021).

Akin to Figure 1, data on total Bitcoins circulated on quarterly basis from 2012 through 2020 are presented in Table 1 and Figure 2. Statistics in the table and figure depict a significant increase in the total number of Bitcoins circulated between fourth quarter of 2012 and fourth quarter of 2014.

The global virtual currency markets recorded about 28.84% ((13,670,000 – 10,610,000) ÷ 10,610,000) x 100% = (3,060,000 ÷ 10,610,000) x 100% = 0.28840716 x 100% = 28.8407 = 28.84%) increase in total Bitcoins circulated between 2012 (10,610,000) and 2014 (13,670,000).

This was higher than the estimated 17.63% increase recorded between 2014 and 2016. Similarly, actual total Bitcoins circulated between 2014 and 2016 increased by 2,410,000. This was low compared to the 3,060,000 increase recorded between 2012 and 2014.

The data suggest demand for and corresponding supply of Bitcoin between 2012 and 2014 were higher than between 2014 and 2016. This notwithstanding, total supply of Bitcoins in the global virtual currency markets did not decrease; supply increased steadily from 2014 through 2016.

Between 2016 and 2018, the global virtual currency markets witnessed 1,370,000 increase (17,450,000 – 16,080,000 = 1,370,000) in total Bitcoins circulated. This was equivalent to an 8.52% increase during the period.

Steady increase in total Bitcoins circulated implies uncertainties in the mainstream global financial markets had little adverse impact on the circulation and performance of Bitcoin on the various virtual exchanges – and minimal negative effect on the performance of Bitcoin in terms of pricing in the global business environment.

The highest percentage increase (3.70%) in circulated Bitcoins was recorded in the third quarter of 2013. Conversely, the lowest percentage increase (0.43%) in circulated Bitcoins was recorded in the third quarter of 2020.

Reiff (2020) and Chan (n.d.) noted the availability of over two thousand cryptocurrencies in circulation. However, it is worth reiterating a significant proportion of total cryptocurrencies circulated globally is contributed by Bitcoin.

Theoretically and practically, Bitcoin continues to assert its role as the original cryptocurrency through increased number of circulated cryptocurrencies, and higher market capitalisation value in the virtual financial markets across the globe. Data in column 3, Table 1, indicate percentage increase in Bitcoins circulated on quarterly basis throughout the period under review.

A common trend observed in the data in column 3, Table 1, is a parsimonious increase in circulated Bitcoins; the estimated percentage increase in circulated Bitcoins for each quarter is less than 4%. Average percentage increase in circulated Bitcoins from the fourth quarter of 2012 through the fourth quarter of 2020 is 1.72%. Marginal percentage increases in quarterly circulated Bitcoins were recorded from the fourth quarter of 2018 through the fourth quarter of 2020.

Glassnode (as cited in Faridi, 2021) provided on-chain market analysis of Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies in the global virtual currency markets. Glassnode’s analysis (as cited in Faridi, 2021) revealed about 14.5 million of the 18.6 million Bitcoins circulated were being held by illiquid companies.

This number represented approximately 77.97% ((14.5 million ÷ 18.6 million) x 100% = 0.779699 x 100 = 77.9699 = 77.97%) of total Bitcoins circulated. The report suggested investors in the virtual currency markets trade in Bitcoins more as a store of value than for day-to-day transactions and payments purposes – implying investors’ preference for Bitcoin as financial investment tool was on the increase during the research period.

Total Bitcoins circulated increased from 17.45 million in 2018 to 18.6 million in 2020, suggesting a differential increase of 1.15 million. The latter represents about 6.59% increase over the period.

Author’s Note

The above write-up was extracted from an earlier publication on ‘Effect of Bitcoin Trading on the Global Economy’ by Ashley (2022) in the Global Scientific Journal.