Nigeria. Africa’s most populous nation has banned foreign models and British accents from the world of advertising and voiceovers. The announcement gained global headlines, and was splattered across social media.

The specific call is that all adverts, advertising and marketing communications materials can only use Nigerian models and voice-over artists. According to research from Nigeria’s Association of Advertising Agencies, 50% of models used in advertising are non-Nigerian, and all the voice-overs were British accents – and that’s from the last ten years. The Association spoke of an escalating pressure and emerging pride among younger Nigerians who would call out advertisers with a derisive – ‘there are 200 million of us – are you telling me you couldn’t find one of us to advertise this product?’ The combination of pressure and pride from the people then moved to policy. And ultimately, that became legislation that is now a ban.

Apparently, there are other such bans in other African nations – but they are unwritten. This matters. The formalizing of a ban through legislation moves pressure and pride into politics and policy. It is this connection between the people and their leaders that is a lesson for Africa and how Africans shape and move their own nations in ways that serve its future, and dismantle its colonial legacy. Policy rarely emerges without pressure, and pressure requires people galvanized, organized and strategizing.

There was celebration and critique of the ban’s announcement.

Let’s explore both.

CELEBRATION

The celebration was an outpouring of ‘about time’, and an honoring of a beauty that reflected the millions who live, love and work in a nation – and whose products will now reflect them. There is a transformed economy. The world of advertising and beauty now recycles its Naira inside of its economy. There is the potential Continent-wide ripple effect. We are an imports-driven Continent. Colonialism’s legacy means Africa is treated as a land of raw mineral extraction, minus the added value and crucial revenue of internal product manufacturing. Internal product manufacture would be an economic game-changer. Nigeria’s advertising and voice-over market just expanded a revenue chain in developing an advertising structure rooted and privileging its own nation – it became a game-changer.

There are bigger celebrations worth noting here too. Beauty and Blackness. The default beauty standard is unAfrican. It is a standard that has built a multi-billion dollar industry in bleaching creams used globally across Africa, Asia, the Middle East, Latin America, the Caribbean and Europe. We have seen that here in Ghana too – products featuring models who bare little resemblance to the particular beauty of Blackness across the 16 regions of mother Ghana.

The world of beauty has been dominated by a Eurocentric aesthetic for decades. One of the legacies of enslavement and colonialism are beauty ideals that move a people as far as possible from their indigenous skin, hair, tone, voice and features.

The work of the visionary scholar Dr. Yaba Blay is instructive here. Dr. Blay’s work is in the politics of black beauty, and has long advocated for a more structural approach that requires the dismantling of white supremacy, and its default narrative that the beauty standard is not Africa, does not look Black, and must be as close to white as possible. Dr. Blay argues that institutional beauty standards and not individual beauty choices should always be the focus of our ire. That approach would transform how we think about and engage issues about Blackness and beauty.

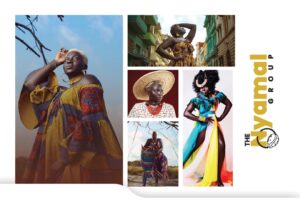

The other element for me in all of this is: healing. The ban is centering a Blackness that reflects the visual make-up of a people in a world where we are shaped by a language of whiteness that created a false narrative of Africa and Africans as inferior. This narrative has a legacy that manifests in how so many African nations move, lead and work. This healing is a balm for beauty, blackness and building our future. The work of The Nyamal Group explores healing through beauty via workshops, dialogues and campaigns on the Continent. Led by Nyamal Tutdeal, a Ghana-dweller of South Sudanese origin, her organization explores conflict resolution connected to our own relationship with blackness and beauty, that can shape how we see ourselves, and requires healing.

This healing matters for Africans and Africa. It may be strange to attach the word healing to the world of beauty and blackness, but it’s not. There is a trauma connected to beauty and Blackness. It is a trauma from navigating a world that consistently considers your particular Blackness as other, ugly, less than, and undesirable. There is a legacy to that trauma. I do not suggest the ban ends the trauma. No. Healing, Blackness and beauty is not a one and done scenario. It is steps. And this move by Nigeria is a step, an important one.

Ultimately, the reality of boosted economy recycled within an African nation at a time when economies are reeling from the devastation of COVID makes the ban a celebration. The marriage of grass-roots pressure, national pride and policy shift is the desired threesome that creates change that champions an African desirability to her citizens. The importance of Blackness and Beauty honoring its own reflection on a Continent and in products is an issue of healing via national pride. It is a healing that is possible due to seeing yourself as your nation’s beauty standard.

The other part of the ban is voice overs with British accents. Voices. Our mother tongue. Our way of speaking is part of our way of being. Voice-overs in accents of former colonizers speaks a particular legacy into the ears and souls of the millions who hear this accent and this sound. Across English speaking Africa, there is a particular respect for accents that are not African. I speak as a Ghanaian with a British accent, who has experienced this when I travel. When I lived in New York, and worked in media, there is a respect afforded a British accent, an assumption of intelligence. To be clear, one accent doesn’t make you smart, just as another doesn’t make you stupid. That notion of intelligence and Britishness also harkens back to history. America is the offspring of Britain, and once again there are notions of superiority and inferiority within these assumptions to navigate and overcome. Overcome them, we must.

CRITIQUE

There was also fierce critique from Nigeria’s announcement. A major one was xenophobia. The critiques – primarily across social media – was that such a move is xenophobic, and discriminates against white models. Well, that is the result of a newspaper headline taking the language of the statement, which actually said: ‘Nigeria bans foreign models’, and replacing the word ‘foreign’ with the word ‘white’. That journalistic sensationalist choice ignited a fire storm. But if it was white models being banned – would such a move be xenophobic? Really? What a strange critique this is.

One thing that strikes me moving around the world is that because the default standard of beauty is white, any attempts to remove it from occupying the centre are derided as xenophobic. I mean, think about it – British accents on voiceovers for products in an African nation? Why would that make sense? It only makes sense if there is a lingering belief that this is the best accent, the standard of what would be persuasive, given that advertising is the world of persuasion. That requires some deep reflection on those calling this xenophobia. There is a difference between a market that is inclusive, and one where a particular people have dominated – and that people are part of the colonial legacy you fought against to acquire a type of independence.

Nigeria’s ban is a step forward in Africa’s leadership choosing its own voice to build economies that will serve the progress Africa requires. That voice is more than sound, it is vision – the vision of a Continent making strides to build its own economy. From how we speak to how we look, whenever we choose ourselves, we win, we thrive, we grow, we strive, we build.

Nigeria’s ban is Africa’s win. Forward ever.