In the wake of COVID-19, governments across the globe are becoming more indebted than at any point in modern history. However, the pandemic is not solely to blame for the elevated debt levels as debt was already rising steadily going into the crisis. According to the World Bank, the “fourth wave of debt” started to crest in 2010, with the largest, fastest, and most broad-based increase in debt in emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs) in five decades. By 2019, government debts across the globe had risen to 84 percent of the global Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

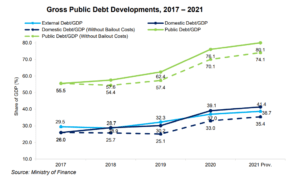

Ghana’s rapid pace of public debt accumulation is one of the most talked about economic challenges in the country, creating growing concerns about debt sustainability and debt servicing capacity. Ghana’s total debt at the close of 2019 was GH¢218 billion, or 62.4 percent of the country’s GDP. The pandemic has worsened Ghana’s debt issues as the government borrows to finance an economic response to COVID-19.

At the end of March 2022, Ghana’s public debt stock remarkably shot up by GH¢40.1billion to GH¢391.9billion according to the Summary of Economic and Financial Data by the Bank of Ghana. Ghana’s central bank now estimates the nation’s debt-to-GDP ratio at 78 percent. However, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) had in its April 2022 Fiscal Monitor predicted Ghana’s debt to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) ratio at 84.6 percent in 2022. These estimates are expected to climb to as high as 88.4 percent in 2026 before making marginal declines to 87.4 percent in 2027. The nation’s debt stock is not sustainable as the cost of refinancing keeps rising as access to the international capital market dwindles.

Insatiable taste for Eurobonds

In 1995, South Africa issued its first Eurobond, marking the start of an era where international financial markets opened a window for African governments to diversify their funding sources from traditional multilateral institutions and foreign aid. Since then, African governments have frequented the international financial markets in search of funds, with Ghana prominently featured among the top issuers.

In 2018 Ghana accessed the international sovereign bond markets to raise a total of US$2billion. Ghana again raised US3billion (about US$100 per person in Ghana) of Eurobonds in March 2019 – a 50 percent increase over the previous year’s issue. Citing COVID-19, the government of Ghana went back to the international capital market to raise another US$3billion each in 2020 and 2021. Since its debut in 2007, Ghana has made eight issuances on the international capital market to raise funds. Over the last four years, the government has borrowed a total of US$11billion in Eurobonds with maturity extending as far as 2060. With an outstanding Eurobond debt, every Ghanaian owes about US$328.78 to international lenders. This reinforces the argument of debt unsustainability in the country.

A huge burden for our children

Governments across the globe borrow to support public expenditure and investments, which can stimulate economic growth. When borrowed funds are efficiently used, the benefits outweigh the cost. That notwithstanding, the level of public debt should be kept at sustainable levels to avoid creating debt traps for future generations. In 2020 Ghana issued its first 40-year bond – a bond that was at the time sub-Saharan Africa’s longest-ever Eurobond. Surprisingly, government leaders lavished accolades on themselves while ignoring the enormous burden put on present and future generations.

The government’s overall debt management strategies include the extension of tenor, introduction of new instruments, and effective communication with the markets. None of these lessen the debt burden on our children. As more and more debt is accrued for today’s consumption, the burden is shifted to future generations – some of whom may never taste their gains. Governments in the fourth republic are actively rolling over maturing debt instead of paying them off prudently.

In most cases, these rollovers are for extended periods, increasing the maturity periods. Unlike developed economies where public debt is accrued to finance new infrastructure or improve existing ones, Ghana is constantly accumulating huge public debt to finance consumption (payment of salaries, end-of-term benefits for politicians, allowances for government appointees, etc.).

For instance, in 2021, the government allocated GH¢30.3billion out of a total expenditure budget of GH¢113.8billion for compensation while only GH¢11.4billion was on capital projects. Of the GH¢113.8billion total expenditure, GH¢41.3billion will be financed by borrowing from the international and domestic markets. In cases where these loans are invested in improving infrastructure, the high levels of corruption do not allow for quality infrastructure to be built. Hence, public goods that have an estimated life span of 30 years only survive for 10 years, resulting in no or very little benefit for our children.

Collateralising future income

Another worrying trend is the collateralisation of future national income such as tax revenues and royalties. Under this practice, the government grants a lender a right over its revenue streams, which allow for the lender to rely on the revenue stream to secure repayment of the debt in case the government defaults. In other words, it entails the government granting liens over specific future receivables to a lender as security against repayment of the loan. According to the IMF, collateralisation tends to be higher in times of stress, or in lending to countries with a risky borrower profile.

This explains Ghana’s recent high appetite for collateralisation – a major example is the collateralisation of future bauxite proceeds for a US$2billion Sinohydro loan facility, as noted in a 2019 joint World Bank-IMF debt sustainability analysis of Ghana. Having been downgraded by rating agencies, the managers of the economy have turned their attention to collateralising future income to contract huge loans. This phenomenon not only deprives unborn generations of the benefits from public revenues, but also mounts a huge burden on the current generation. For instance, as oil prices rise, the government is unable to remove the various ‘nuisance’ taxes placed on consumers of petroleum products because the government has collateralised those taxes through the energy sector levy (ESLA).

Policy options

It is evident that governments – past and current – have not been fair to future generations. In Ghanaian popular culture, a good father accumulates wealth, and not debt, for his descendants. Past and current managers of the economy cannot with clear conscience heap huge debt obligations on unborn generations. We must adopt and implement bold and futuristic policies that create generational wealth for future citizens and change the current narrative. The following policy options will help secure our future, and that of future generations:

- Rationalise public spending: Governments must be confident enough to cut expenditures that plunge the nation into unsustainable debt levels. For instance, end-of-service benefits, popularly known as ex-gratia, paid to article 71 holders are a major financial drawback to national development. It is not only unfair to dole out huge sums of money to a selected few while other public sector workers, who have served the nation diligently, are paid meager pensions. Payment of huge ex-gratia are a huge financial burden, and, in some cases, governments borrow to meet this constitutionally mandated payment. How can a nation spend so much on a few elites against the interest of future citizens? Why should we borrow at market rates to pay end-of-service benefits? Scrapping ex-gratia will require bold leadership but it must be done to save the nation.

- Explore innovative financing options, such as blended finance, to leverage traditional sources of funds to raise private capital at below market rates. These approaches also use philanthropic funds to encourage private capital flow into strategic projects which will stimulate economic growth.

- Reserve and invest part of the revenue from non-renewable resources: Ghana has huge natural resources ranging from gold, bauxite, oil, manganese, and others. Unfortunately, most of these natural resources are non-renewable. Hence, as governments earn revenues from the extraction of non-renewable resources, they must invest portions for the benefit of future generations. The establishment of the Ghana Heritage Fund (GHF) to support development for future generations when the petroleum reserves have been depleted is a step in the right direction. However, such funds or reserves must be free of political interference and used only for the benefit of future generations.

Borrowing is not necessarily a dreadful thing – nations across different historical periods have borrowed for one reason or the other, and continue to borrow. However, as much as we care about meeting current financial demands, it is only fair to review the impact of today’s borrowings on future citizens. The current pattern of unsustainable debt build-up is the most heinous form of injustice we can inflict on our unborn children. As a developing nation, we have an obligation to protect the interests of future generations by building sustainable economies that eliminate cyclical poverty and can compare with other economic superpowers. A decent parent leaves a legacy for his children rather than massive debts.

The writer is s development finance enthusiast and digital media expert