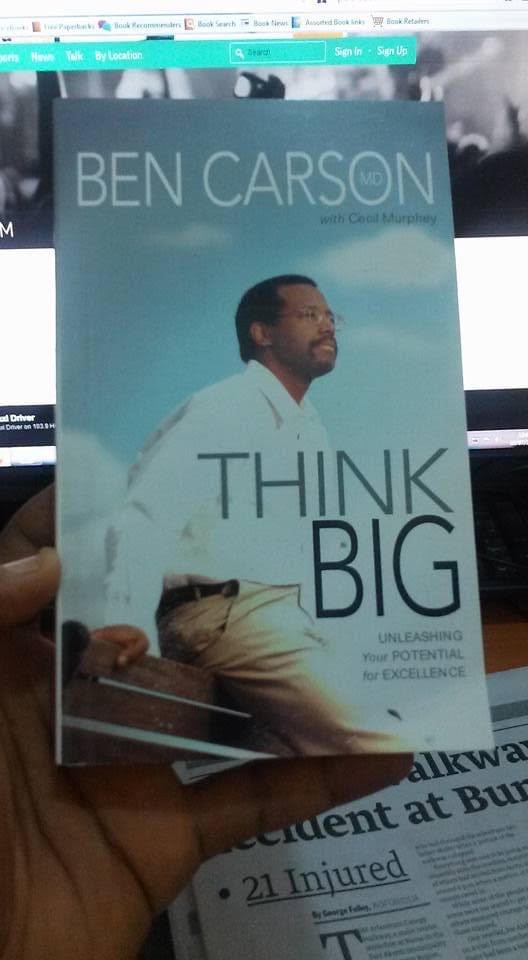

‘Think Big’ is a bestselling book authored by the world premiere neurosurgeon, Prof. Benjamin Solomon Carson Sr. The first to have successfully separated twins conjoined at the head. The groundbreaking record stands as a yardstick, looking at how possible Prof. Benjamin Carson rose from failure to a saviour, with a pivotal role played by his mother, Sonya Carson.

In our world today, it’s always difficult for a second to pass without families spending their leisure in front of a television. The television has become a beloved spouse and progeny. When it happens this way, it’s rather the children who suffer most. They neglect their books and would give the television their topmost priority.

Sonya Carson had only a third-grade education, or would better be referred as unlettered because she could hardly recognise words in a sentence. Also, a poverty-stricken single parent with two sons -Curtis Carson, 10 years, the eldest; followed by Benjamin Carson, 8 years. And has had to choose between committing suicide and seeking the success of her sons. Thus, she settled on doing a number of menial jobs for the rich in order to keep her family afloat. Survival and success are her compass.

Out of those multiple jobs, she became abreast with how the rich live their lives. The rich families she worked for all had a television (five or six sets) but hardly did they watch them. Chunk of their time goes into reading and analysing materials. Their choice of clothing is mainly on its quality, not faddishness.

But all these came with a big price – not being able to monitor her sons when they came home after school due to the demands of work. Mostly, Sonya came home when they were long asleep. In so doing, Curtis and Benjamin spent all their precious hours in front of the television. They watched everything shown until bedtime bids.

In fifth grade, Benjamin’s report card revealed (though as a kid, he never wanted his mother to have seen his report card but it couldn’t manifest) his abysmal performance and utter emptiness in the head when they came to Boston, from Detroit. This afforded his classmates the privilege to term him as the ‘dumbes’ kid in class. With time, little Benjamin learned that he was indeed stupid!

That said, the unthinkable happened when Sonya came home an hour before bedtime and saw her sons stretched themselves in the couch, glued to the television. She hastily turned off the television and said: “You’re wasting too much of your time in front of the television. You don’t get an education from staring at the television all the time.”

In furtherance of Sonya’s agitation, she issued a stern warning that no more television for the boys except for two selected programmes each week. But that would come into being when they are done with their homework; if not, they’re not required to be seen playing outside after school.

Curtis, the rebellious, remained shush. Whereas Ben rather saw this new motherly decree as stringent for them, as kids. So he retorted: “Everybody plays outside.”

Another back and forth ensued. But eventually, their mother won them over by standing firm to her words. “Don’t worry about everybody else,” she turned the tables over, “the world is full of ‘everybody else’, you know that? But only few make significant achievement.”

Their mother passed another robust decree that they’d have to begin “reading two books” in a week, and write a report on them. Benjamin was in fifth grade, but he hadn’t read a whole book ever in his life before. It was always the television. Now his right of watching his favourite programmes was being cut away, as they do to the umbilical cord after delivery.

Benjamin, seemingly struggling not only with maths, his report card revealed that all subjects were his pet peeves. He’d have to begin with learning the times table and cramming them into memory. This would solidly be done via reading, and nothing more. No other option.

Since Sonya had showed them the way to the library, they went there. How much they wished they had died than go to the library to read! After a series of confrontation with the librarian, they got to settle on a book to pick.

For instance, Ben picked ‘Chip, the Dam Builder’. A kids’ story about the beaver. He got himself so gripped with the book that just by two nights, once in his lifetime, he completed reading a book.

In just a month, Ben could walk to the children section of the library as though he had lived all his life there. They now became fond of books. Benjamin upgraded from reading books about animals to rocks. And for the first time, he saw that he’s having a practical knowledge of rocks in the books he read. Verily, there’s more in the library than on the television. Reading is beneficial than watching of toys and cartoons.

Times that they’d walk along the railroad tracks, he carried his book along, just to ensure that he could trace correctly the names and features of stones he had labelled. Even Curtis, his elder brother, became tired of his (Ben’s) penchant of picking stones and identifying them.

The essence of reading manifested in the life of Ben while fifth-grade was almost coming to an end.

One day, as their dictation session was ongoing, the entire class was quiet. Mrs. Williamson had dared Bobby farmer, the brilliant boy, in their class, to spell ‘agriculture’.

While Bobby farmer was garnering the alphabets to spell the word ‘agriculture’, Ben realised that he had seen the word ‘agriculture’ in a book he had read day before.

Just as reading permits the mind’s eye to own and recognise words, however spindly they appear. He, thus, managed and spelt it correctly under his breath, even before Bobby farmer spelt it audibly and he received the necessary commendation.

A week later, in class, Mr. Jaeck, their science teacher, was then teaching the class volcanoes, and he showed them a blackish, glass-like rock. “Does anybody know what this is? What does it have to do with volcanoes?”

Benjamin had already recognised the stone because he had seen it in his reading about rocks. All the smartest kids in the class have become like dead bodies; they were shushed.

As soon as Ben had raised his hand to be given the opportunity to answer, they were resuscitated because the dumbest boy was about to show his folly once again. They murmured. They saw Ben’s confidence as an effrontery and craziest joke of the time!

“It’s obsidian”, Ben mentioned. Though the teacher and his classmates remained not startled, they knew heaven had broken loose. The undoable has happened. Ben just didn’t name the stone, he also talked about its formation and other features. That was sensational. Credit to reading!

Reading became so habitual that Benjamin never missed the television, nor cared about playing Tip the Top, neither baseball. He always wanted to do nothing but read, and read.

The good news is that in eleventh grade, Benjamin had almost become the smartest kid in his class. Not only did he conquer math; he topped all other topics. The achievements and beautiful grades kept dazzling.

Once, they had an exam (advanced math) which came with two extra questions. The known smartest kid in the class scored 91. And Ben who, could hardly score a mark in math, had everything correct, 110 marks! When this smartest boy learned of Ben’s scores, he sadly turned away.

Benjamin’s reading habit grew increasingly, and in Yale University, he could start reading from six in the morning to eleven at night. He read comprehensively. When he picked a topic, he ensured that he dissected and digested it all because reading, since childhood, had become fun.

For example, when the question: “What’s the hormonal imbalance that one gets with Cushing’s Disease?” appeared on a test, he trusted himself of knowing the required answer, and could even expand his answer by providing the underlying mechanism of the hormonal imbalance although no professor would ask such a question at medical school.

He just knew all that because of his reading lust. Benjamin would often say that the more he studied, the more he knew he was on the road of becoming a good doctor.

In 1988, two years after the release of Ben Carson’s autobiography – Gifted Hands, students had begun forming reading clubs, chronicling it after his name.

To become a member, one would need to promise three things: (1) that he’d read two books a week, (2) to submit a reading report on each book to the club, and (3) limit time spent in watching television.

The group functioned so well. The young boys and girls encouraged themselves. Slow readers got anchored by the fast readers. Powerful analysis followed the completion of a book. Those students who couldn’t make the grades started making them. The poor performing students also began climbing to the top. Maybe we’d have to call reading the grades-making-incubator.

Unlike reading, television, in times before, brought to these students an already packaged knowledge like how to dress (sagging and other preposterous style of dressing), think, and behave awkwardly; the ceaseless alcoholic advertisements, etc. The television, indeed, doesn’t truly stimulate the child’s intellect.

For sure, “reading activates and exercises the mind. It forces the mind to discriminate. From the beginning, readers have to recognise letters printed on the page, make them into the words, then into sentences, and the sentences into concepts.” Reading enforce the use of one’s imagination and thus, leave one creatively inclined.

It’s this pragmatic reading time table drawn by a single (divorced) and unlettered mother, Sonya Carson, who is very conscious of God, and their (her sons) endeavour to shun the television and hold fast to reading which shot them far above the skies.

Curtis became a successful aeronautical engineer, and Ben Carson, a professor of neurosurgery, plastic surgery, oncology, and pediatrics, and the director of pediatric neurosurgery at Johns Hopkins Medical institution. He’s a bestselling author and holds a cornucopia of magnificent achievements.

Now we can broadly conclude that there are three elements which parents mustn’t allow to go missing while turning the hearts of their children: (1) God, (2) reading, and (3) good manners!

And sincerely, Helen Hayes once said: “When books are opened, we discover that we have wings.” With books, your child can fly to any altitude in success.