As G20 ministers and central bank governors gather in Bali this week, they face a global economic outlook that has darkened significantly.

When the G20 last met in April, the IMF had just cut its global growth forecast to 3.6 percent for this year and next—and we warned this could get worse given potential downside risks. Since then, several of those risks have materialized—and the multiple crises facing the world have intensified.

The human tragedy of the war in Ukraine has worsened. So, too, has its economic impact especially through commodity price shocks that are slowing growth and exacerbating a cost-of-living crisis that affects hundreds of millions of people—and especially poor people who cannot afford to feed their families. And it’s only getting worse.

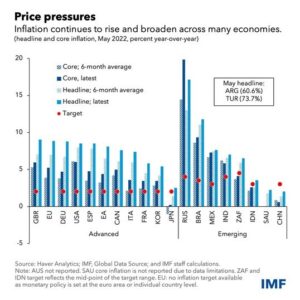

Inflation is higher than expected and has broadened beyond food and energy prices. This has prompted major central banks to announce further monetary tightening—which is necessary but will weigh on the recovery. Continuing pandemic-related disruptions—especially in China—and renewed bottlenecks in global supply chains have hampered economic activity.

As a result, recent indicators imply a weak second quarter—and we will be projecting a further downgrade to global growth for both 2022 and 2023 in our World Economic Outlook Update later this month.

Indeed, the outlook remains extremely uncertain. Think of how further disruption in the natural gas supply to Europe could plunge many economies into recession and trigger a global energy crisis. This is just one of the factors that could worsen an already difficult situation.

It is going to be a tough 2022—and possibly an even tougher 2023, with increased risk of recession.

That is why we need decisive action and strong international cooperation, led by the G20. Our new report to the G20 outlines policies that countries can use to navigate this sea of troubles. Let me highlight three priorities.

First, countries must do everything in their power to bring down high inflation.

Why? Because persistently high inflation could sink the recovery and further damage living standards, particularly for the vulnerable. Inflation has already reached multi-decade highs in many countries, with both headline and core inflation continuing to rise.

This has triggered a monetary tightening cycle that is increasingly synchronized: 75 central banks—or about three-quarters of the central banks we track—have raised interest rates since July 2021. And, on average, they have done so 3.8 times. For emerging and developing economies, where policy rates were lifted sooner, the average total rate increase has been 3 percentage points—almost double the 1.7 percentage points for advanced economies.

Most central banks will need to continue to tighten monetary policy decisively. This is especially urgent where inflation expectations are starting to de-anchor. Without action, these countries could face a destructive wage-price spiral that would require more forceful monetary tightening, with even more harm to growth and employment.

Acting now will hurt less than acting later.

Equally important is clear communication of these policy actions. This is about preserving policy credibility as downside risks abound. For example, continued inflation surprises would require a sharper monetary tightening beyond what the market has priced in, potentially causing further volatility and sell-offs in risk assets and sovereign bond markets. This, in turn, could prompt further capital outflows from emerging and developing economies.

The appreciation of the US dollar has already coincided with portfolio outflows from emerging markets: they experienced a fourth consecutive month of outflows in June, the longest such run in seven years. This is putting additional pressure on vulnerable countries.

Where external shocks are so disruptive, they cannot be absorbed by flexible exchange rates alone, policymakers should be ready to act. For example: through foreign exchange interventions or capital flow management measures in a crisis scenario—to help anchor expectations. In addition, they should pre-emptively reduce reliance on foreign currency borrowing where debt levels are high. It was to help countries respond in such circumstances that we recently updated the IMF’s institutional view on this issue.

The Fund is stepping up to serve our members in other ways as well. This includes providing advice on managing reserve assets and technical assistance to strengthen central bank communications.

The goal must be to get everyone safely to the other side of this tightening cycle.

Second, fiscal policy must help—and not hinder—central bank efforts to bring down inflation.

Countries facing elevated debt levels will also need to tighten their fiscal policy. This will help reduce the burden of increasingly expensive borrowing and—at the same time—complement monetary efforts to tame inflation.

In countries where recovery from the pandemic is more advanced, shifting away from extraordinary fiscal support will help tamp down demand and thus reduce price pressures.

But that is only part of the story. Some people will need more support, not less.

This requires targeted and temporary measures to support vulnerable households facing renewed shocks, especially from high energy or food prices. Here, direct cash transfers have proven to be effective, rather than distortionary subsidies or price controls that typically fail to reduce the cost of living in a durable way.

Over the medium-term, structural reforms are also crucial to bolster growth: think of labor market policies that help people join the workforce, especially women.

New measures must be budget-neutral—funded through new revenues or expenditure reductions elsewhere, without incurring fresh debt and to avoid working against monetary policy. This new era of record indebtedness and higher interest rates makes all this doubly important.

Reducing debt is an urgent necessity—especially in emerging and developing economies with liabilities denominated in foreign exchange (FX) that are more vulnerable to tightening global financial conditions and where borrowing costs are surging.

Already, sovereign FX bond yields have reached more than 10 percent in around a third of emerging economies—close to the highs last seen after the global financial crisis. Emerging economies with a greater reliance on domestic borrowing, such as in Asia, have been more insulated. But a broadening of inflation pressures and the attendant need to tighten domestic monetary policy faster could change the calculation.

The situation is increasingly grave for economies in or near debt distress, including 30 percent of emerging market countries and 60 percent of low-income nations.

Again, the Fund is here for its members—offering tailored analysis and advice, and a more agile lending framework to support countries in times of crisis. That includes emergency financing, increased access limits, new liquidity and credit lines, and last year’s historic SDR allocation of $650 billion.

Beyond these efforts, decisive action by all involved is urgently needed to improve and implement the G20’s Common Framework for debt treatment. Large lenders—both sovereign and private—need to step up and play their part. Time is not on our side. It is critical that creditor committees for Chad, Ethiopia, and Zambia deliver as much progress as possible at their meetings this month.

Third, we need a fresh impetus for global cooperation—led by the G20.

To avoid potential crises and boost growth and productivity, more coordinated international action is urgently needed. The key is to build on recent progress in areas ranging from taxation and trade to pandemic preparedness and climate change. The G20’s new $1.1 billion fund for pandemic prevention and preparedness shows what is possible, as do recent successes at the World Trade Organization.

Most urgent of all is action to alleviate the cost-of-living crisis, which is pushing an additional 71 million people into extreme poverty in the world’s poorest countries, according to the United Nations Development Programme. As concerns over food and energy supplies increase, risks of social instability are rising.

To avoid further hunger, malnutrition and migration, the world’s wealthier countries should provide urgent support for those in need, including with new bilateral and multilateral financing, especially through the World Food Programme.

As an immediate step, countries must reverse recently imposed restrictions on food exports. Why? Because such restrictions are both harmful and ineffective in stabilizing domestic prices. Further measures are also needed to strengthen supply chains and to help vulnerable countries adapt food production to cope with climate change.

Here, too, the IMF is helping. We are working closely with our international partners, including through a new multilateral food security initiative. Our new Resilience and Sustainability Trust will provide $45 billion in concessional financing for vulnerable countries—aimed at addressing longer-term challenges such as climate change and future pandemics. And we are ready to do more.

The particularly difficult conditions in many African countries at this moment is important to consider. In my meeting with Ministers of Finance and Central Bank Governors from the continent this week, many highlighted how the effects of this, entirely exogenous, shock was pushing their economies to the brink. The effect of higher food prices is being felt acutely as food accounts for a higher share of income. Inflation, fiscal, debt and balance of payments pressures are all intensifying. Most are now completely shut out from global financial markets; and unlike other regions don’t have large domestic markets to turn to. Against this backdrop, they are calling on the international community to come up with bold measures to support their people. This is a call we need to heed.

As the G20 meets to navigate the current sea of troubles, we can all take inspiration from a Balinese phrase that captures the spirit that is needed more than ever— menyama braya, “everyone is a brother or sister.